Welcome to Remarkable People.

This week’s Remarkable People podcast features a woman who fell in love with the Monterey Bay while studying science at U.C. Santa Cruz.

On many dark, dank, and cold mornings, Julie Packard waded through the icy waters of the intertidal zone to study the plants and animals. She did this as research about the impact of humans on the Central California coast.

In the late seventies David Packard, half of the founding team of Hewlett-Packard Company, challenged his children to come up with a big project that would make a difference in the world.

Julie’s sister Nancy, Nancy’s husband, and a couple of friends came up with a concept for an aquarium. Eventually, this led to her father and mother investing $55 million to fund what is now the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

Initial studies projected 350,000 visitors a year. Year one drew nearly 2.4 million people.

Since its opening day on October 20th, 1984, the Monterey Bay Aquarium has introduced over 60 million people to the incredible sea life off the Central California Coast, as well as the vast ocean beyond.

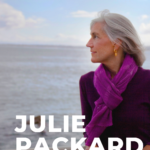

Julie is the executive director of the Monterey Bay Aquarium and an international leader in the field of ocean conservation. She is also a leading voice for science-based policy reform in support of a healthy ocean.

Can you guess what sea animal she’d like to come back as? Stay tuned, and you’ll soon find out.

Her philosophy is to learn something every day, work with great people, and motivate them to make the world a better place.

This is Guy Kawasaki and this is the Remarkable People podcast. And now here’s Julie Packard.

© Monterey Bay Aquarium, photo by Tom O’Neal

What did you learn from this episode of Remarkable People?

This week’s question is:

Where could you spend time to help the planet? We can all do a little more. 🌎🐡#remarkablepeople #questionoftheday Click To TweetUse the #remarkablepeople hashtag to join the conversation!

Where to subscribe: Apple Podcast | Google Podcasts

Find more from Julie Packard

Follow Remarkable People Host, Guy Kawasaki

Guy Kawasaki: This is Guy Kawasaki, and this is the Remarkable People Podcast, and now, here's Julie Packard. Guy Kawasaki: This is Guy Kawasaki, and this was the Remarkable People Podcast. Thanks to the Remarkable People Podcast team of, Jeff Seih, Peg Fitzpatrick, Marley Morgan and Neil Pearlberg. They keep my ocean blue and teaming with great content. This is Remarkable People.

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

This week's Remarkable People Podcast features a woman who fell in love with the Monterey bay while studying science at UC Santa Cruz. On many dark, dank and cold mornings, Julie Packard: waded through the icy waters of the intertidal zone to study the plants and animals. She did this as research about the impact of humans on the central California coast.

In the late seventies, David Packard, half of the founding team of Hewlett-Packard, challenged his children to come up with a big project that would make a difference in the world. Julie's sister, Nancy, Nancy's husband, and a couple of friends came up with the concept of an aquarium. Eventually, this led to her father and mother investing $55 million to fund what is now the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

Initial studies projected 350,000 visitors a year. Year one drew 2.4 million people. Since its opening day on October 20th, 1984, the Monterey Bay Aquarium has introduced over sixty million people to the incredible sea life off the central California coast, as well as the vast ocean beyond.

Julie is the executive director of the Monterey Bay Aquarium and an international leader in the field of ocean conservation. She's also a leading voice for science-based policy reform in support of a healthy ocean.

Can you guess what sea animal she'd like to come back as? Stay tuned, and you'll soon find out.

Her philosophy is to learn something every day, work with great people and motivate them to make the world a better place.

For me, and I think many people, 367 Addison is the center of the universe. It's like where time began. You didn't live there?

Julie Packard:

No. I'm so sorry to say. That is like a shrine to the tech community, for sure, but my three older siblings were born there, but by the time I came around, my dad had decided he wanted to move up into the hills.

He was born in Pueblo, Colorado in a really rural town. I don't know if any of the listeners have been to Pueblo, but there's not a whole lot going on. It's right at the edge of the Prairie in Colorado. He was just super outdoorsy. He secretly wanted to be a farmer/rancher, I think, before he became an engineering genius.

They moved from Palo Alto up to Los Altos Hills in the fifties, and then where I was born. So, no, sadly I didn't live at Addison…

Guy Kawasaki:

Wah

Julie Packard:

I don't have any stories. You'd have to interview my older siblings for that.

Guy Kawasaki:

But still, you did grow up in the family that, arguably, started Silicon Valley. What was that like?

Julie Packard:

Things were very different back then. First of all, just setting the scene. We moved up in the Hills-- in Los Altos Hills-- kind of above what's now Foothill College. Back then it was just apricot orchards and oak forest.

You look out over the valley, there was of course hardly any urbanization at all, and so it was very rural and a lot quieter back then, of course. Growing up, probably like most kids in the fifties, my dad worked all the time. No surprise.

My mother was very traditional, and there were four of us in the family. For her, it was about being supportive, raising your kids with manners and good values, but we had a great place to grow up.

My dad bought this apricot orchard. We spent our summers in the orchard cutting the apricots to make dried apricots to sell.

My dad, as I said, love vegetable gardening and growing stuff. He was this huge nature lover, but it had to be functional-- hunting, fishing, growing things, cattle ranching. He loved driving tractors. He'd get out of the tractor and, like, adjust the orchard every spring and drive the tractor around, and then the summer apricots would be harvested and we'd sell them to the canneries.

Back then, Santa Clara valley, there were all the apricot and prune and cherry orchards, so there were canneries down there. You'd sell the fresh fruit. Then over time, of course it was all urbanized but, we still continued to cut dried apricots, sun dried apricots-- Blenheim’s, the best you can get them at the farmer's market.

Now that is an insider tip to everyone in California. Look for the Blenheim apricots. They're the best.

Guy Kawasaki:

This is the farmer's market on Sunday?

Julie Packard:

Just any farmer's market in the Bay Area. You can find them. They're the old-school kind to grow in the Valley of the heart's delight, which is what they called Santa Clara Valley because great fruit-growing.

My dad worked a lot, and he was very imposing. You needed to maintain a low profile at the dinner table, and he'd always win every argument with you.

I mean many of us I'm sure grew up in families like that. He just had such huge curiosity and just seemed to know everything about everything and what he didn't know, he would read. He just had an incredible library of just the biggest array of subject matter from calculating, plumbing types for his irrigation system, to the future of the defense industry in Russia.

Guy Kawasaki:

Did he come home and say, "Oh, today we got an order for 10,000, oscilloscopes from Disney." Nothing like that? “We just invented reverse Polish notation calculators.” Nothing like that?

Julie Packard:

He would tell us about all of those things and we thought they were very exciting and remarkable. We knew all of those things were a very big deal for sure.

For me personally, though, you have to understand, I came of age in the sixties, and that was a time when there was just a lot of unrest, a lot of protesting about the military industrial complex, and HP was a big defense contractor.

I personally, I always tried to maintain a really low profile about kind of-- t the time my dad's company, because of the political times, there was controversy around it. Now, tech has sort of just revered as everyone's in love with it, but…

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, other than Facebook…

Julie Packard:

Not so much, but I mean, generally speaking, those were very unsettled interesting times, but yeah, my dad would share all those things and where they just blow us away. They were so cool.

Guy Kawasaki:

Did it ever come to a point where you were philosophically opposed saying, "Dad, how can your company empower the military industrial complex?"

Julie Packard:

Me, personally?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Julie Packard:

Well, absolutely. I was the youngest in the family and definitely a bit of the black sheep. How would I say it? Between the times, and being the youngest, I think, or just being very independent, sure, I have those thoughts, but you didn't take my dad on about things. There was no... nothing. No good could come of it. Let's just say that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you have any particular lessons you look back-- I can tell you what I learned from my father, the three or four most important things. You have a small number of things you can say? “My father relayed…?

Julie Packard:

Yeah, absolutely. My dad was incredibly humble.

I mean, arrogance was considered in our family, the absolute worst qualities. We always were taught, and he modeled, that we were very fortunate and we needed to be humble about that and not ever be arrogant in any way. Not just having to do with money, but just in general, the privileges that we had, of course, which he created for the family. That was a big family value.

Giving back, certainly because my parents established their family foundation early on, it was in the sixties, and it's 1965, The Packard Foundation is now fifty years old, and so early on, they established a family foundation and began supporting first, community projects. The company was always very supportive and giving back to the community. In fact, my dad was an early supporter of the whole idea of corporate philanthropy, which, in my opinion, still has a long way to go.

If he were alive, he'd still be out there proselytizing about that, that companies need to reinvest in their communities. He believed that, and my mother actually ran the foundation early on as a volunteer and was very involved as a community volunteer. That was modeled for us majorly, the idea of giving back and engaging in your community.

I thought she had a full-time job growing up, honestly, and she didn't. She was a full-time volunteer, but she was always gone all day, or I'd be in the parking lot in the car while she was volunteering on some board for the children's hospital or something like this.

Guy Kawasaki:

What did you learn from her?

Julie Packard:

Well, very similar values to my dad, really. She was quite proper. She was a city girl. She wasn't an outdoorsy, nature lover like my dad.

She grew up in San Francisco, and went to Catholic school and was very refined. We needed to reflect well on her father at all times and have good manners and be presentable like any mother.

I mean, I don't know that's kind of mother job description 101. Isn't it? Those were two things, I think, the humility and the giving back. The final thing I'd say about my dad, he would listen to anyone. I mean, his HP's management by wandering around, that he wrote about in his book The HP Way, of course, is an epic philosophy in the management literature.

His door was truly, always open. He liked talking to an employee at the lowest level in the company, as much as, or even actually more than, at a higher level, to be honest.

He just loved getting in and talking to the team about what project they were working on. He really did the whole idea of investing in people and giving them rain to do their best work, which was an HP philosophy. It's also the philosophy of our family foundation is invest in people and their ideas. He really modeled that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now let's talk about the Genesis of the aquarium. How did that come to be?

Julie Packard:

The aquarium was the brainchild of my sister and her husband and a couple of their colleagues. Here's how the story happened.

The family foundation, The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, we were founded in the mid-sixties. The four of us children were asked to be on the board, instructed to be on the board when we turned twenty-one. The foundation was funding a lot of different programs in different areas.

My father kind of challenged the group, "Hey, let's think of some big projects that we can do that are really all around rather than just funding other people's ideas."

It was my older sister, Nancy, and as I said, her husband and a couple of their friends that were involved with teaching and research down at Stanford's Marine Lab, Hopkins Marine Station, the Marine laboratories in Pacific Grove.

Stanford had purchased this big old cannery right next door, the Hovden Cannery, where the aquarium is now located. They didn't really have plans for it. It was just too buffer zone for all the development in cannery row.

They had the idea that this would be just a super cool thing to do with this old cannery and that, in Monterey, there was no place for all the tourists to learn anything about the bay, and yet that's why they came there.

We're all marine biologists. The four of them were invertebrate zoologists, and I studied marine algae. None of us were fish people or marine mammal people, but we had fallen in love with the ocean and marine biology because of Monterey bay. This bay was just an inspiration. It's an amazing place. It's amazing rich biodiversity.

We put together a proposal to the foundation to do this ability study if an aquarium was built on the site, could it be financially self-supporting based on admission fees, and would there be enough attendance to support it? That came out with a “yes.” With that, we incorporated a new foundation, the Monterey Bay Aquarium Foundation to plan, build and operate this aquarium. My parents put up the capital, $55 million to build it. The deal was that operate on its own.

We proceeded to put together a board of local community leaders and scientists from around, we have such an amazing scientific community here around the bay, science leaders, and family members and hired architects and exhibit design consultants, and a crazy array of specialized consulting help that you need to put together an esoteric kind of institution like an aquarium, and set ourselves to planning this aquarium.

The concept remained the same from the start, which was to do a tour of Monterey Bay habitats and kind of have that be a theme. A few ideas about the aquarium were different than other aquariums before.

One, first of all, most aquariums are rows and rows of fish tanks. Certainly, there were at the time and that's not what that ocean's like. Fish were just a little tiny part of what the oceans like. We want to really share the whole picture. We want to share it in a way where the plants and animals are represented as they would be in nature, meaning in communities, kelp forest or rocky reef or sandy sea floor.

Of course, we have this amazing site with the real thing outdoors, which really no other aquarium has a site that fabulous. Most aquariums are in the dark when you think about it. You're in the dark, because that actually makes, from an exhibit design standpoint, that makes the tanks pop. The fish look great, the tanks look great, but, like, "Wow, we got the real thing out here, this wild ocean."

We wanted to design that really drew your attention to the real thing outdoors and get people out on the decks. And then they could come inside and learn about what they had seen or the other way around.

And then finally, we really wanted to... well, two other things that were kind of important points about the concept. One was: we didn't want people to be in a one-way path. We wanted it to be free choice. You could experience it however you wanted in whatever order you wanted.

And then, finally, we wanted to really incorporate some of the new museum interpretive techniques that were happening at the science museums, like the Exploratorium, what we all know as interactive exhibits, where people are engaged with the learning.

Previously, a lot of aquariums were really a tank with fish and a label. “Here's the name, here's where it's from, here's what it eats.” Maybe another little factor too. We wanted to just make it a more interesting and engaging experience, have more interactive kind of hands-on interpretations.

Those were some of the underlying concepts. We naively thought we could remodel that old cannery. Wow, that talks about the, or shows, the level-- like I said, ask us about marine algae ecology, and we can nail it.

Anyway, we were, like, "We're going to remodel this cool old building." The building was built in 1916. It was, I believe, the largest cannery in cannery row, but those canneries were just... I mean, it was such a boom and bust thing.

They'd make it... they were just canning. They were harvesting and canning just tens of millions of tons of sardines. They'd add onto their buildings, they'd have a good year and then things would go along. I mean, they were just-- you can still see, sadly, not many, but you can still see some remnants in cannery row of some of those old buildings.

We wanted to-- we thought we could remodel the building. Of course, we were quickly disposed of that notion by the architects and engineers, but we were really happy with the concept architects came up with, which really was preserving the facade on cannery row of that old building. We kept the old boilers, are still a history exhibit when you go in the aquarium.

It turns out, Knut Hovden, who was the owner of the cannery, was known to be an incredible innovator. Kind of like my dad, he invented a lot of new technology for sardine canning to make it go faster and to make the product better. One of which was to-- he had a seawater system. A sea water intake line that went into that building just like the aquarium does. That was kind of a cool thing.

The idea was, instead of having all the sardine boats offload the sardines at the dock where they start rotting and they're not fresh and then you have this giant pile of sardines at the cannery, and it's a big processing logistics problem, he came up with the idea of these floating, giant wooden boxes. They’re called sardine hoppers. They were off shore and connected to a seawater intake pipe, and then offload the sardines out there, they'd stay all fresh, and then they suck them into the building as they needed them to can them.

The building, actually, was registered on what's called the Historic American Engineering Record that we have document all of his canning technology. That's a little backstory about the site of the aquarium, which is amazing. That was the creation story. It was about seven years between the time of the idea and the feasibility study, and then all the design. It took a really long time to get the permits.

That was a lot of drama because a city limit line between Monterey and Pacific Grove runs right through the aquarium site, which of course just complicated matters. We have the Coastal commission, the Army Corps of Engineers, and just a lot of agency engagement, but then we opened on October 20th, 1984.

Guy Kawasaki:

Did anybody fight it?

Julie Packard:

Well, that would be a whole other long story. We got engaged in some opposition that was really around local politics around land use planning decisions that were coming down at the time. They didn't have to do with the merits of the project. Everyone thought the project sounded great-- what a gift to the community!

Most public aquariums are on city property, or they're funded by the city, or they're partially funded by the city, or they got an operating subsidy, so we're just, "Hello. We're going to pay for this site. We're going to provide the capital to build this building. We're not asking you for any operating subsidy. We're asking you for the aquarium visitors to be part of the parking district,” which is a gold mine for the city.

We had opposition, but that's a whole other story. It was just local politics.

Guy Kawasaki:

Has it evolved from an aquarium to more cause orientation?

Julie Packard:

Absolutely. We're just celebrating thirty-five years this year. We had a huge evolution in our mission, which is actually reflected in our mission statement.

When we began, the purpose statement for the Monterey Bay Aquarium was something like, “To expand public awareness, conduct research,” and maybe have promote stewardship in there, at the Monterey Bay. What happened over time, as we all know, is the ocean changed.

In our understanding of what was happening in the ocean, has undergone a transformation, not a big enough transformation in terms of public awareness, but thirty years ago, everyone still thought the ocean was so vast that nothing could possibly affect it. As our stories that we're telling about the bay and the ocean at large continued to evolve and stay up with the times, we realized that we really wanted and needed-- it was really imperative for us to start talking more and more about the human impact stories of what was happening on the ocean and not just the happy, natural history stories about the cool fish and their weird habits, which is great.

Obviously, that's what gets people to come in the door and fall in love with the animals and gets their attention, but we needed to add on a new species to the aquarium interpretation, which was humans. Because the original aquarium, we didn't really have humans so much as part of the story. We, over time, kind of transformed all of our interpretation to have more human impact, human stories, more conservation stories, and then, eventually, decided to do an exhibit called Fishing for Solutions: What's the Catch? That we did in the mid-nineties, right after we had opened our open sea wing and taken our story offshore to connect with the broader ocean.

Fishing for Solutions, we thought, “Okay, the situation, the ocean is getting dire, we need to do an exhibit about global fisheries and all the problems.” We did that exhibit.

In the course of it, we decided that we better get our restaurant menu, seafood item list in shape, or would not look good. From that whole effort, the Seafood Watch program was spawned, so to speak.

The Seafood Watch began as just a consumer guide to enable people to know the sustainability of the seafood on their plates. Around that time, then we realized this was really a big deal. It really picked up. With that, around that time, we decided to make a commitment to grow that program and also to launch a real conservation and science work group and big effort at the aquarium. The seafood work is at the centerpiece of that, but with that, we also changed our mission statement, which was a big milestone for us to what it is today, which is the mission of the Monterey Bay Aquarium is to inspire conservation of the ocean.

The idea behind that, being that the end game, the end goal, of the whole institution and everything we do is about ocean conservation, but the word inspire in there is really important because we're a public institution, and our best asset for achieving that goal in the ocean is the aquarium itself.

Our challenge and the, the beauty of what we do is that we have this amazing institution that inspires people, that can inspire people, through connections with living animals and discovering the ocean, the real thing.

Guy Kawasaki:

In a prior life, I was on the board of the Stanford Alumni Association, and we had many a meeting discussing the mission of the Stanford Alumni Associations. Honestly, it was pulling teeth. I'm just curious, was this something that your board, your trustees, you all got together and said, “Let's do this,” or did you bring in McKinsey and they charge you five million bucks to get that sentence? How did that go down?

Julie Packard:

Like with most things probably is the theme in your podcasts here, if you’re talking to leaders, is it really came down to leadership. It came down to me. I'm front and center, all conservation, all the time. I mean, that's what motivates me. That's how I-- it’s my lens in life because of my life experience growing up.

Our board, when I sat in, and our team too, I mean, I think that our team was, "Hey, Julie. You're wanting us to do more and more of this conservation stuff. It's gotten to where we need to really make it official or do something, kind of codify it more." Also, because for the team, the main activities of the aquarium, we've got the public side, the aquarium, the visitor experience, we've got all of our K-12 education programs and then we have research, which again is mainly conducted by the embargoed Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute.

But we just really needed to restate what is the priority here. The word got out. Some of the people were like absolute advocates, helping me push that through.

A couple of the more business oriented ones were a little concerned that, “Okay, this is going to sound like we're going to become an advocacy organization,” or “Sounds like NRDC,” or some super lefty conservation, environmental agitators. Of course, we're not, and we didn't intend to do that, but there was a little bit of concern about what does this mean, or what are the optics of this.

But in the end, the people around the table were—You kind of can't argue with, “Okay, the ocean... things are getting dire. We have this huge power to inform and engage and ignite the public.” From our team's perspective, that is the end goal. What's the outcome goal? Everything we do? Sure, we’re a lot of the education programs. Sure, we’re improving stem education and we’re concerned about-- we were doing a lot of things, but we just...we needed to provide focus.

One of my favorite things about the aquarium is the fact that we are viewed as non-partisan. Everyone loves bringing their kids to the zoo or an aquarium. It's a happy thing, no matter-- you might be the most right-wing Republican known to humanity, or super lefty, but you're comfortable.

We want the aquarium to be a comfortable place for everyone to come and have a great day. We need to continue to be that place that's open to all. I'm most excited about reaching the people that maybe haven't thought about the ocean and the importance of engaging in the actions that we need to take to ensure that it's healthy for the future for the benefit of humanity. The people that already are Sierra Club members. Some were kind of like, “That's fine,” but they're already there.

My goal is to get them to realize the ocean-- If you care about saving nature, you need to talk about the ocean because the ocean is the biggest part of nature. That's where we, being land dwelling species, the whole environmental movement is so much focused on land as it should, and as is understandable, the ocean has got profound influence on everything else.

Guy Kawasaki:

No one has ever made the case, “Well, if you're listing the right kind of seafood and all that, you're affecting jobs.” Not like, “We need coal because there's 50,000 coal miners.”

Julie Packard:

Interestingly, the Seafood Watch program, which now is a global program, it's a global fisheries and agriculture program, we are super business-friendly. We're in the continuum of organizations working on this issue of over-fishing, which is a serious problem and something that we know how to fix. I mean, that's the reason to work on it.

You might think, “Oh, seafood, whatever. What about plastic and climate change and all of that?” We can talk about those things, but the thing about fishing is it's the most ancient relationship that humans have with the ocean. It's the only place where we're still extracting, at least certainly the industrialized world is, still extracting wildlife on a market basis.

We think it's fine for people to be fishing, and we're here to help transform the seafood and aquaculture business enterprise to one that can be more sustainable into the future. We take heat from environmental groups and certainly we take heat from business. We used to take mostly heat from business early on, as you said, because they're like, "Hey, you're saying now that the Patagonian toothfish is on the seafood watch avoid list. We think that's unfair."

The whole point is-- we're like, "Well, come meet with us. If you fix these two problems, next time around, you'll get a better rating." It's been a huge driver. I mean, businesses really pay attention to it, what their rating is. It's quite fascinating and become much more powerful than we thought.

Guy Kawasaki:

What would it environmentalist say against you?

Julie Packard:

Well, that we are too friendly to fishing and that we should become-

Guy Kawasaki:

Not hard enough?

Julie Packard:

... that we should all become vegans, and we shouldn't need any seafood.

Guy Kawasaki:

And you don't believe that?

Julie Packard:

Well, no. I think that would be great for nature. I just tend to go for more practical solutions. I feel like there's big money in the seafood enterprise.

I mean, two points: One, it's big business. It's not going away anytime soon, so let's work to make it better.

It is jobs, it's millions of jobs, mainly in developing countries, and aquaculture is growing like gangbusters and it provides jobs. It's food security if we can do it right. It's not going away, if we can do it right, let's go for it. Let's work to have that all happen in a better way.

As far as catching wild fish, fisheries are resilient. As it turns out, if you lay off them, when they've been over-fish, they will recover.

Now in the big scheme of things, is the ocean a lot more depauperate than it was 200 years ago? Yes, it is.

For those who say, "Well, in the best of all worlds, humans would quit extracting any life out of the ocean." Yeah, sure. That would be wonderful. I mean, something like, I don't know, over a billion people depend on seafood for their primary protein. There's a big food security question here, and livelihoods of millions of people in coastal economies.

I guess on top of it, you have countries where people are moving up in the middle-class, and it is really increasing demand for beef and meat. That's a whole other, I think, really worthy consideration to say, “Hey, if the world ate less animal protein, it would have really positive impacts on climate and a lot of other things.”

I don't argue with those points of view. I think that's all true. We're just focusing on the seafood situation and making a lot of progress. It's quite remarkable. There's a lot more to do, though.

Guy Kawasaki:

How do you audit or determine what's on that seafood watch lists? Do you depend on other researchers or you do first-hand research?

Julie Packard:

Seafood Watch rating system is based on published, available research. People get confused about it. It's not a third-party certified audited program. If you go into your Safeway, and there's a piece of fish there, it's not going to say, “This fish is a piece of halibut, and we've...” Well, first of all, any fish caught in the U.S. is always a good choice these days. It didn't use to be, but if you want to really play it safe, buy something caught in the U.S fishery, because at least we have regulations and even our fisheries that were depleted, they're recovering. In some cases, it's going to take a long time.

But that piece of fish and the store that you're buying, it has the Seafood Watch reading of yellow or green, it means that we have evaluated against the set of criteria that I can talk about the sustainability of that particular fish. The Alaskan halibut fishery, as an example, it doesn't say that we know that that piece of halibut is a piece of halibut. It doesn't say that we know that that piece of halibut came from Alaska because that would require that we are doing an audit program.

Now, there is a program that does that that's called the Marine Stewardship Council, which is the next level. Seafood Watch is just a set of standards for businesses and fisheries to aspire to. It's an involuntary program. We rate all these fisheries, whether you want us to or not. They're a transparent bunch of ratings about sustainability of these different fisheries.

Marine Stewardship Council was an organization started by World Wildlife Fund in Unilever, I don't know, over twenty years ago, that does provide third party certification, and they have their criteria.

If you're MSC certified, it means that your fishery has met the sustainability criteria and you've been inspected to, and you're reporting back, and the third-party certifier is saying, “Yeah, you are…” and you have to get recertified every five years. That's complicated.

That's probably all you need to know about it for the moment, but I'm always happy to talk more about it. I think it's fascinating, but I'm kind of a nerd on the topic because it's making so much progress, it's really exciting. I mean, there's just a lot of good stuff going on.

Guy Kawasaki:

You seem excited and optimistic, whereas you read this gigantic Pacific island plastic patch... or what is the greatest threat to the ocean?

Julie Packard:

Well, the greatest threat to the ocean, no surprise, carbon pollution, climate change, climate crisis, whatever the current lingo is for it. I mean, clearly, it's like the mother of all environmental issues in any environmental issue that you can think of.

Twenty years ago, whatever we said the problem was, now it's like, “It's just like an existential threat.” When it comes to the ocean, obviously, we read about sea level rise, which of course mainly people are focusing on whether their home's going to be inundated, which is a serious problem to consider.

here's a tremendous amount of coastal habitat that contains a huge amount of biodiversity that is changing, is going to be continued to be altered, and just affects entire ecosystems that we can't even imagine, but the big threat that people are just beginning to talk about, which is just insanely concerning, is the whole ocean acidification thing, which is, as CO2 goes in ocean water, it makes it more acidic. Those changes are happening already.

As the water becomes more acidic, it's just going to cause-- it already is causing-- changes. Whether from animals, big to small, that have calcium in their cell walls and their shells, that can't form, but also just physiological systems that we don't even… We're just beginning to understand what those might be.

That's going to have profound effect, and then the ocean warming, which is already happening. Of course, we're experiencing that right here in our part of the world in the central coast.

Scientists have documented species shifts where we see more southerly species living up here than we did twenty years ago, just in my lifetime, since I've been out in the tide pools, doing research and collecting algae and in looking at animals. That's happening. The climate change is a huge deal and sort of the mother of all issues.

I mean, whether it's coral bleaching or impacts of warm water, the whole ocean food web. The one thing about it, that most people don't know, is the ocean is really-- I started to talk about the ocean as our best-- healthy ocean is our best defense against damaging climate change. The reason is the ocean has absorbed something like ninety percent of the heat generated from burning fossil fuels since the industrial revolution. I mean, think about that. The ocean is like a giant modulator of heat in the atmosphere and the whole global system. Number one.

Then number two, all the plant life, the little microscopic plankton plants that live in the ocean are photosynthesizing and sucking up CO2. The ocean absorbs something like twenty-five percent of the carbon emissions. That's huge too. That all happens because of a living ocean.

I mean, all of that CO2 uptake by those tiny plants, if the ocean's dead, that's not happening. That's pretty much... they end life on the planet. Not to be a downer, but it's big. It's really big.

Of course, also the ocean plants produce a lot of oxygen. A lot of that is consumed by life in the ocean, but it is a vast part of the system that makes life able to exist on earth.

Guy Kawasaki:

If a random person is listening to this podcast and thinking, “Oh my God. I believe it. I buy it. Everything you just said,” What can one person do not in charge of a foundation?

Julie Packard:

I think... Of course, I'm asked that a lot. Over two million people that come to the Monterey Bay Aquarium every year, they definitely ask us that all the time. "Wow, okay. I love the ocean. I love these animals. I want my grandkids to see them, and I want us all to-- I want humanity to survive and thrive as long as we can on this planet. What can I do?" I answered that question in a couple of ways.

I mean, first of all, just get engaged in the process of political action in your community, in your state, in your nation. People need to get out and engage and get the right people in charge of these decisions because our environment is a comment, but something that society needs to decide for the benefit of everyone, what the rules are.

The way we've been operating, there's just a huge amount of extracting of resources and damaging of ecosystem services that we all depend and on. Change happens. Start local. That's where the change begins.

In these days, certainly in the U.S. where I know people are probably feeling rather deflated about how much leadership we can provide and we feel like we're losing ground, which we are, in terms of a lot of the excellent environmental protections. The good news here in the U.S. is a lot of great stuff's happening at the state level. California, for example, the best thing anyone living in California right now can do is support our state, or wherever your state is, support its leadership because what's happened here in California, whether it's the progress on environmental policy, I mean, we've always led the way in environmental policies here in our state. It hasn't exactly been at the cost of our economy, by the way.

I mean, tourism and the tech sector, like huge. Of course, tourism depends on taking care of your environment. All of that's happened because voters care. They voted. They put the right people in office. They supported huge public funding initiatives. I mean, we've had these five-billion-dollar land and water protection bond initiatives in California to-- we've created the first and only integrated network of marine protected areas in California state waters. That was a first in the U.S. anywhere.

We have an incredible network of protected lands, protected coastal lands. People drive from San Francisco to LA, and they're always kind of shocked.

You have almost forty million people living here in the state, and this looks so great. Monterey Bay itself, the central coast, is totally reviving and thriving. When BBC came out, they were looking at doing a live broadcast about the ocean, Big Blue Live. Of all the places in the world, they picked Monterey Bay to do this live nature broadcast, which was fantastic. I mean, we have whales and lake sharks and everything under the sun!

I say, get involved in your community and the support policies. That's the best thing you can do, and of course changes in your personal life. I would say the whole seafood movement and the improvement in sustainable seafood, U.S. consumers making the right choice, has driven a huge amount of business change. That really makes a difference. The same thing can happen with plastic too. I know everyone's very concerned about that.

Over time, if people start showing that we really don't need so much single-use plastic, it can make a difference.

Guy Kawasaki:

If I were going to go for seafood dinner, is there anything I just should not eat? Because I'm not checking labels unless the waiter brings out whatever.

Julie Packard:

You should be. You should be checking your Seafood Watch app. Now, what you need to be looking for along with…Or you go out to dinner with me, I pull up my app. Are you kidding?

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, yeah?

Julie Packard:

Rule the waiter. Actually, the best thing consumers can do-- we've done so much public opinion polling about this whole seafood thing. People say-- Public says their best source of information about sustainable seafood is their wait person or the person at seafood counter.

Well, it turns out the wait person usually doesn't know anything. The only reason, the only way they're going to get to know something is by all of us asking questions. That's one of the key messages on our Seafood Watch pocket guide--

Guy Kawasaki:

Ask questions.

Julie Packard:

Ask questions. Ask questions. Ask your wait person, “Where did this fish come from? Is it sustainable? And how do you know?” They'll tell you.

Now, many, many restaurants these days, in coastal states, certainly in the west coast states, definitely not in the inland states and probably less so on the east coastal states, restaurants will refer to-- they'll use it as a sales point. They'll say, "Our seafood is sustainable per Monterey Bay Aquarium guidelines,” but you're safe with things caught in the U.S. pretty much. Pretty much, we're okay, and local fish.

Local U.S. fish we've been really promoting. All of our ground fish fisheries here in California are reopened after being declared a federal disaster and being closed for over a decade. Ask with the local fisheries if you're in the U.S. and you'll be good. Here, that means like rockfish and ling cod and sea bass…

Guy Kawasaki:

Isn't it counterintuitive you're saying, we want to preserve the ocean and preserve wildlife. Wouldn't that say, “Well, don't eat from local fisheries because they're fishing right here and reducing our population right here?”

Julie Packard:

Well, the important thing isn't whether it's right here, the important thing is does it have good regulation? That's the thing. One thing I will say, because the whole local movement, which we are all aware of, certainly in our part of the world, here in Santa Cruz, California.

Here's the crazy thing. The United States imports eighty percent of the seafood we eat and we export ninety percent of the seafood that we catch. Makes no sense.

If you're going to own a restaurant in the U.S., chances are the fish did not come from here. It came from another country because in the U.S., the U.S market, which is-- we're, I think, the third biggest market for seafood in the world now. Even though you and I might think, “How often do we eat seafood?” Americans eat a lot of seafood. We're a big driver in the global seafood market.

Biggest thing Americans eat: farm shrimp, farm salmon, and so both of those products are really bad news in terms of the environment. Our team at the aquarium is working hard to improve standards. That's another story, because those were both farm products.

One of the things that's been really tough on all of our local fishing communities along the coast of the U.S. is all this imported seafood, because no one's buying local seafood anymore. They don't eat-- there's not even a distribution system, to be honest. It's crazy. That's starting to change. The more people that eat local is a really good thing for people to ask about.

Guy Kawasaki:

What's wrong with farmed?

Julie Packard:

Farm can be fine. It's just the way it's happening now is bad news. The main things are: salmon farms use a lot of antibiotics. That's a huge issue. They create a lot of fish waste in a really concentrated area. Can be equivalent to like a raw sewage outfall of the mid-sized city in one spot. That can create a dead zone in the area.

The farm salmon, they get diseases that people are concerned can spread to wild salmon in areas where wild salmon exist. In some areas, that's not an issue of wild salmon doesn’t exist there. The fish can escape and breed with a wild fish and pollute the gene pool.

Guy Kawasaki:

If there is another life, what would you want to come back as? What animal or plant or...

Julie Packard:

Well if it includes plants, that's problem because I'm a botanist, but I'm going to stick with animal. My favorite fish is this crazy fish, it's called Mola-Mola, the Latin name. It's an ocean sunfish. People would come to the aquarium, if you go to the big open sea exhibit, you'll recognize it. It can grow to be the size of a Volkswagen bug. It looks like a big dinner plate with a fin sticking up off the top and the bottom. It's the world's largest bony fish. I'm a huge fan for a lot of reasons.

One, it has no commercial value. No one seems to care about this poor fish. We have myriad scientific research papers on tunas and sharks, the stuff we like to eat and the scary stuff, this Mola, which is like the coolest looking animal ever, no data whatsoever. The aquarium, we're doing some tagging studies. Nothing likes to eat it.

It's got really thick skin. It doesn't taste good, which is who I want to be. Animals are going to leave me. No one's going to be after me. If I'm a 2000 pound Mola, I'm pretty safe. Even though I swim really slowly, I can't keep up, I can't get out of the way. I just grow big, really fast.

Then, the other thing is, I eat jelly fish-- jellies. The future ocean, a lot of the scientists are saying that...one doom-and-gloom scientist is saying, the future ocean will be a world of slime. What that means is the oxygen levels in the ocean are declining over time. These layers of these oxygen minimum layers, they call them. Jellies have super low metabolism, and they can live in really funky conditions. So whatever happens in the ocean…

Guy Kawasaki:

You've lots to eat.

Julie Packard:

I've got lots to eat, and I can swim to my preferred water temperature zone if the ocean temperature changes. I'm thinking that's maybe the animal to be.

Guy Kawasaki:

What do you want your legacy to be?

Julie Packard:

I am super proud of all that the Monterey Bay Aquarium has accomplished. Our team has just taken it so far beyond anything wildly imaginable. I'm just really happy that I've had the opportunity so far in continuing to open people's eyes to this, what I like to call the other part of the planet that we've just now woken up to, that makes humanity able to exist here on this beautiful earth.

If I can, if I have a spark, the engagement and dedication and motivation of a few people, whether they're teachers or kids, future advocates that will carry on, that's something that I'll feel really good about.

Guy Kawasaki:

But as I did my research on you, one of the most interesting things is you are the antithesis of a trust fund baby, but you are the daughter of the first one who created Silicon Valley, but you're not a trust fund baby. How did that work out? I mean, you're the exception.

Julie Packard:

I got asked that actually by people these days who have come on to a lot of success in raising children and they're like, "Wow, you actually-

Guy Kawasaki:

“What happened to you?”

Julie Packard:

... something productive? How did that happen?" I mean, all I can say about it, it's really about what kind of parents we are and how-- and it's not what we say, it's who we are and how we lead our lives. That's the most important thing. My parents, they were all about being productive, contributing, working hard. Even though I grew up in the fifties, and at that time, the women, the girls-- I have two sisters. We weren't really expected-- My dad had a lot of expectations placed on my brother, big time expectations. The girls, it was, “You've got to do really well in school and work really hard and give back to society.” The kind of pain job expectation was a little vague. It was important to find a good husband. Those were the times. Go to a good university…

Guy Kawasaki:

It was important to find a good husband?

Julie Packard:

Yes, or a mother. Yes, yes, because those were the times. But my dad, if there was one message I got from him was, “Don't be a slacker. Work hard all the time at what you are doing and be contributing in some way.”

Maybe if one of us wanted to take some time off and have children, look after the kids for a while, but even so, and all of us in the family, whether we go into a job every day or whatever we're doing, everyone is doing some big projects to make the world a better place in some fashion. That's just because that's what our parents did.

Guy Kawasaki:

If you're ever anywhere near the Monterey Bay area, you must visit the Monterey Bay Aquarium. It will blow your mind.

Now, you know about the Mola-Mola, specifically that it eats jellyfish, which is likely to be in good supply. If you are a Mola-Mola, no one's going to want to eat you. If anyone would know what fish to be, it's Julie Packard: Executive Director of the Monterey Bay Aquarium.

Special thanks to Kevin Connor and Terry and Will Mayo who made this podcast possible. Finally, special thanks to Michael and Caitlyn Tee of Crate. They helped me figure out how to recover a corrupted Zoom H6 file. If they hadn't done that, and if I had to tell Julie Packard that I lost the file, and if she had said, “Tough luck,” there would not be this podcast. Thank you, Michael and Caitlyn, Jeff, Peg, Marley, Neil, Kevin, Terry, and Will. It takes a village to make a podcast.

Sign up to receive email updates

Wondering what 367 Addison is? Google Maps and Wikipedia

Julie’s point about more people taking actions, engaging, in a variety of ways to help move us from the affects of climate change was valuable. There’s something everyone can do with greater or lesser positive effects.