Welcome to Remarkable People. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Dr. Chika Oriuwa.

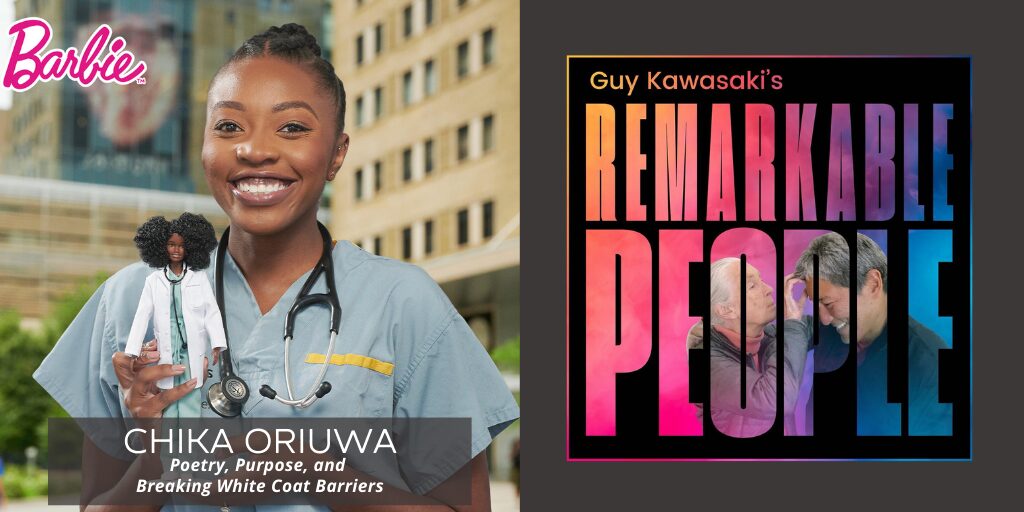

Dr. Oriuwa is no ordinary physician; she’s a force for transformation in modern medicine. As the only Black student in her class of 259 at the University of Toronto Medical School, she turned that solitary position into a platform for change. Her powerful memoir Unlike the Rest: A Doctor’s Story chronicles this extraordinary journey. But her impact extends far beyond the halls of medicine – she’s also a nationally ranked slam poet, author, and was honored as a Barbie role model.

In this episode, we dive into Dr. Oriuwa’s extraordinary journey, exploring how she combines the precision of medicine with the power of poetry, her experience confronting systemic barriers, and her vision for a more inclusive healthcare system. Her powerful story demonstrates how authentic leadership and unwavering determination can create lasting change.

Throughout our conversation, Dr. Oriuwa shares the transformative moment when she performed a deeply personal poem during her medical school interview, capturing the attention and respect of her interviewer. She discusses her experience as the only Black student in her medical school class and how she channeled that isolation into creating meaningful change. We also explore the surreal experience of becoming a Barbie role model and having a one-of-a-kind doll created in her likeness. Above all, she shares her ongoing mission to reshape medical education and create a more inclusive healthcare system that serves everyone.

Connect with Dr. Oriuwa and discover more about her journey in her new book Unlike the Rest: A Doctor’s Story, available wherever books are sold.

Please enjoy this remarkable episode, Chika Oriuwa: Poetry, Purpose, and Breaking White Coat Barriers.

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Chika Oriuwa: Poetry, Purpose, and Breaking White Coat Barriers.

Guy Kawasaki:

I only know two Nigerians, you and Lovey. I don't know if you know Lovey.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Oh yes. Well, I don't know her personally, but I follow her on social media. Very cool.

Guy Kawasaki:

We once got into a whole discussion about Nigerian weddings and how to go for three days and stuff. Did you have a Nigerian wedding like that?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

I did.

Guy Kawasaki:

You did?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

It was a very lavish affair, you could say. It was massive. And this was in 2022, so we were just not really coming out of the pandemic, but starting to get a little bit more socially comfortable with the new normal. And we had 600 people at my traditional Nigerian wedding. I know. I'm very proud of my Nigerian culture. I'm very proud of my Igbo culture, but still it was a lot. And then I had our traditional Western white wedding weeks later.

Guy Kawasaki:

One of the people who have been on this podcast is Jon M. Chu, and Jon M. Chu is a director of Crazy Rich Asians. So I could reach out to him and ask him if he wants to make Crazy Rich Nigerians, and he'd love it.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Oh my goodness, that would be a wild time. And I would actually love to see Nigerians painted in that light in the sense, I feel like a lot of African culture doesn't always get painted or seen in that perspective of there's absolutely affluence within African cultures. It's there as well.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let's face it, most Americans think that Africa is a country, not a continent, right?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Yes. And that's something that definitely it gets to me every time I hear people say that.

Guy Kawasaki:

So this initial discussion has been so funny. We'll probably keep it in the podcast, but at some point I should introduce you.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Please.

Guy Kawasaki:

So I'm Guy Kawasaki. You've been already listening to the Remarkable People Podcast, and we're on a mission to make you remarkable. And today we have a remarkable guest who's also been a Barbie role model.

Her name is Chika Oriuwa. She's a remarkable person. She has a background in medicine. She was one out of 259 students who's Black in the University of Toronto Medical School. And she's an activist, a poet, and is outstanding in everything basically. So that's why she's on our podcast. So Chika, welcome to Remarkable People.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Thank you for having me here, Guy, and thank you for that introduction. I'm so honored.

Guy Kawasaki:

I think the honor is mine, but yeah, we won't go there and argue. So I have a question for you, one author to another, because I've authored sixteen books. And I think that one of the hardest things, if not the hardest thing about writing a book is figuring out the title. So I just want to know, having read your book, did you ever consider calling your book Even You as opposed to what you did call your book?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

So the origin story of the title is very interesting. Because when I was finishing writing up the book proposal, which I'm sure you're very familiar with, and getting that big massive document of the outline, and the pitch, and everything, I needed a title in order to submit it to the publisher. And I was like, "I don't know what to put. Unlike the Rest," I thought it was just going to be a placeholder.

But then my agent loved it. My husband was like, "This is a great title." And I was like, "Yeah, okay, we'll just keep it there for now." But as I actually went to write the book, that phrase, “Even You”, it was one of the most resonant, I would say. That it resonated with me, but it also resonated with a lot of the readers when they ended up also reading it.

But I think if there was an alternate title I would give the book, it would probably be Especially Me, which is the line that follows “Even You” in, I believe it's chapter three towards the end of it where I say even me. And then I think especially me. And I think I want that to encapsulate truly what I'm trying to drive home with this book is that we get to define what our greatness is. We get to define what our story is, and I don't want anyone to ever try and take away that ownership or to challenge that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. As I read your book, I said, "Wow, this incident at the American Canadian border." I'll give a little bit of background for the listeners wondering, what the hell are these two people talking about? In about 2013, Chika was in a car with three other girls, and they had just finished some academic work, and they were going from Toronto to Buffalo on a shopping spree.

And at the American border, the American whatever, immigration agent was asking them why they're going to America. And they were explaining what their background was and they're medical school students, and they're on the way to celebrate it, and they're going to Buffalo for shopping.

And when the guard came to Chika in the car, they explained that she's going to be a doctor too. And he said something like, "Even you," in other words, "Even you a Black girl, you could be a doctor." Did I get that story right?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Yes. So with the minor tweak of the detail that I actually don't think I mentioned this in the book, but alongside me in the car were two of my friends who were of Chinese descent, and then one of my friends was Guyanese. And so we were all women of color. And I think that actually brings in an even more interesting analysis because we were all women of color.

However, I was singled out. And I was the only Black individual in the car. And he said, "Even you," when we had clearly stated what our ambitions were and how it was that we knew each other because, "How you guys know each other." We were all undergraduate students at McMaster University in our health sciences program. We all wanted to be doctors.

And so that reflexive questioning of this dream that I've held since I was three years old. In that moment, I was indignant. But I was also a bit scared because this was an authority figure. And so I didn't know how to appropriately measure out and weigh my indignation against what I was taught, which is also always to be very calm and docile in the presence of authority.

Guy Kawasaki:

So are you telling me that even in Canada, Black parents have “the talk” with their kids?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Absolutely. I think because this understanding of the systems of racism are not limited to the American border. This is a ubiquitous, universal experience. When we talk about anti-Blackness, we see it in a global sense. And so when my parents came from Nigeria to Canada in the 1980s, they experienced that racialization, they experienced that anti-Blackness.

And so for my parents, it was never really this sit down talk of, "This is what you're going to go through." It was sprinkled throughout different conversations. It was always a touch point of, "You have to behave in this certain way or else certain things can happen to you."

And really, and I talk about this a lot in my book, Unlike the Rest where I say that my father and his experiences navigating his career as a pharmaceutical technician, as a nurse, and how anti-Blackness impacted him. That when he was trying to spirit me along on this journey of medicine, he always beat into me this humility that in his mind was the way for me to be able to survive a system that also had anti-Blackness in it.

But then the unfortunate outcome was actually trying to make me smaller, to make me less identifiable. In certain ways, to really try and erase all the parts of my identity that I thought that I now know is beautiful, but to him was a bullseye. So it was always an ever-present theme throughout my life.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. So at this point in your career, have you reached a level of accomplishment where you are simply a great doctor, or a great writer, or a great poet, and you know what? It's not that she's the Black person there in the room, she's just fully accomplished. Have you reached that point, or do you think that point is reachable in this society?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

So that's a really interesting question because I think that with writing this book especially, I have viewed it as my biggest act of liberation. And what I mean by that is that I feel that once certain individuals, especially Black people, Black women, once we reach a certain level of accomplishment and success, that sometimes all it is that we are recognized for is how it is that we can contribute say for example, from an EDI perspective or from certain perspectives where our Blackness is at the forefront.

And that is something that is always going to be so vital and critical to who I am, but I don't want it to be the sole way in which I'm defined. And so I felt that for a long time I was seen in almost this one dimensional analysis of my personality, of my skills, of my talents.

And so writing this book for me was in many ways liberating such that I can be seen in the fullness of who it is that I am. The fullness of my humanity, a three-dimensional analysis. Yes, I will always be so exceptionally proud of being a Black woman, and that is something I take pride in. However, I am also a doctor, I'm also a writer. I am a mother, I'm a public speaker, I'm a performer, I'm an author. There's all of these things that I am, and the fullness of that is what I want to be celebrated.

Guy Kawasaki:

Don't take this wrong. But if I were a racist white person, you would be my greatest fear.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

I don't take that wrong because I am so aware of that. I think that our society, an empowered woman is something that terrifies our society. And I don't think we need to look far to see an example of just how afraid our society can get when a woman is audacious, and loud, and intelligent, and successful, and all of the different things.

But when you layer on top of that a racialized woman, a Black woman, again, we needn't look forward to see an example of this. But when you bring in these different intersections, I can see that inherently, individuals are intimidated.

Because I create, and I'm aware of this, I know that there's this creation of this cognitive dissonance. Our understanding, or at least the way in which Black people have been socialized, the way in which the perceptions of Black people have been embedded into our culture is that we are supposed to be less intelligent. Women are supposed to be less intelligent, less accomplished, that African individuals. Again, there is all of these incredibly racist stereotypes about the intelligence of Black women especially.

So then when I show up or when other incredibly intelligent Black women show up like Lovey as well, and we challenge this idea, this long held idea, it creates this cognitive dissonance.

And so some of the ways in which this is reconciled is through that fear. It's through that anger, because usually you are afraid of things or you're angered by things that you don't understand. And so I know that I evoke that emotion, and it's something that I've had to contend with for a long time.

Guy Kawasaki:

I can guess the answer to this question, but I bet you were even more disappointed than I was that Kamala Harris lost the election. We have one of the most qualified candidates against one of the least qualified candidates, and she loses. And I just don't get it.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Yeah, I was devastated. And I think it's interesting, because the American political system is very fascinating because it feels like the whole world holds its breath until we know what's happening. And I think for so many reasons, it's understandable, especially as a Canadian.

We are literally geographically so close, but even culturally in so many of the other ways in which we are reactionary, or we respond in very similar ways to what happens in the states. And very much I felt that a lot of Canadians and a lot of individuals worldwide were taken aback, were disappointed, devastated. I struggled immensely on that morning of the election results when it was declared who had won. And it was really devastating, as I'm sure as it was for a lot of Americans and for you as well.

Guy Kawasaki:

So can we back up for a second? And just tell us the story of you figuring out that of 259 students in the entering class at the University of Toronto Medical School, you are the only Black one. So what was that like?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

To take you back to that exact moment, I would have to give a little bit of a preamble because I had gone into it with such significant expectation. I had just finished my undergraduate program at McMaster University in Hamilton, which is a stone's throw from Toronto. And I was the only Black student in my graduating class in 2015 for my undergraduate program at McMaster.

And out of the medical schools that I'd gotten into, U of T was the only school that had a Black Medical Students Association. And so amongst all of the reasons of why I wanted to go to the University of Toronto, it was close to home. It's an incredibly prestigious medical institution, and it had this Black medical association. I just felt that I was going to deviate from that narrative of being the only Black student.

So when I arrived on the morning of my stethoscope ceremony day and I looked around and I saw them, I didn't really see any other Black students. I thought maybe they just haven't shown up yet. It's orientation week. It's not really the first full week of school.

And so when we got to the actual stethoscope ceremony and they were calling every single student across the stage one by one, and my last name starts with an O, And so I was fairly further on down in the alphabet. And I remember crossing the stage and thinking, "I still have not seen any other Black people."

And then coming off the stage and sitting in the seat of the auditorium and then seeing everyone else go by and thinking, "Oh my gosh," as I'm holding this Hippocratic Oath and we're reciting it. And I'm thinking in the back of my head, there are no other Black people in my class.

259 students in 2016 in downtown Toronto, the most culturally diverse city in this country, one of the most culturally diverse cities in the world. It was absolutely heartbreaking, I would say, but also a disillusionment. I was stunned by. It simply stunned.

Guy Kawasaki:

And I read in your book you faced various kinds of racism, and so perhaps you can explain to people. Because obviously I'm not Black, so I haven't experienced what you experienced, but from that patient who said, "Get all the non-doctors out of this room," and said, "This Black woman, she can't be a doctor, get her out of this room." And some of the interactions you had with your teachers, just explain what kind of racism you encountered. And also for each kind of racism, what should you do?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

The way that I like to break down the different kinds of racism, so there's things known as microaggressions, which are your daily racial slights, racial grievances that on the surface maybe to a desensitized ear, you might not even recognize that it could be something that's racially aggressive.

Case in point, whenever I would meet a patient or another medical student and I was always frequently asked, "Where were you born? Are you Canadian? Are you used to the winters?" It was just a constant assertion and the assumption that I was not of Canadian origin, that I could not have been born. I must have been born elsewhere. So it was this gatekeeping of the Canadian identity that constantly made me have to explain myself even at the outset of a medical encounter.

And then on the opposite side of that are more macro aggressive, more intensely obvious I guess you could say racial grievances where it was a direct challenging of my intelligence, my capacity, my ability to actually be a doctor.

So as you mentioned, having a patient who had directly said that I had to leave the room because I didn't look like a doctor, even though being repeatedly told that I was a part of the medical team. And then still, the patient actually growing more agitated, growing more aggressive because they did not want me in the room.

And bearing in mind that I did not have any training as to how I was supposed to de-escalate that situation, how I was supposed to encounter that situation, although I had specifically asked for that training prior to my clerkship years. And these kinds of experiences, it really permeated my medical education, which was an exemplary medical education at the University of Toronto.

However, I was still facing it from so different angles. So from patients, sometimes from my attendings, from other medical students. And then when I eventually did my public-facing advocacy, then facing it from the public, which was just an entirely different beast unto it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now going back to that incident where that patient asked you or told you to get out of the room, as I recall, you left the room, and you were in tears. And then it was a very traumatic, tearful thing. But looking back, should you have just stood your ground and confronted him and taken him on, or what would you do today if that happened?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

So I would say that firstly, I want to hold grace for where I was in my journey as a medical student. And not necessarily having had the tools, or the understanding, or the insight into what to do in that moment.

And so I did leave the room tearfully. I truly did not know what I was supposed to do alternatively. Interestingly, I mentioned in the book that one of the older fellows, medical fellows had came out afterwards and said, "You should have stayed in the room. That's what you were supposed to do." I think as I said, I give myself grace for where I was in that journey.

Now having my MD, being a doctor, being a resident doctor, if I was in that same situation, what I would do is I would likely stay in the room. I would likely reaffirm to them and reassure them that, "I am a physician, I'm part of the medical team, I am here to help you." And of course if the patient gets increasingly agitated, I would then employ the skills that I've since learned as to how to deescalate that situation.

I also think it helps when institutions, when hospitals have policies that we can actually reflect back to the patient. So this is a teaching hospital. And in a teaching hospital, you have to be seen by the practitioner who is available. And that would be myself.

And if it got to the point where I felt that my safety was actually in peril or that I was about to be physically harmed, of course I would go and get the appropriate resources, the help that's around there as well. But I think where I am now is very different than where I was then all those years ago.

Guy Kawasaki:

You are clearly a better person than I am. There's no question about that. I don't know if I would've done that. I can think of a lot of things, but grace would not be the top of mind for me in that situation.

So you became active after a decision to turn them down, but you changed your mind for the Black student application program. Could you just explain that to me? Because this was something to increase the recruitment of Black students to your medical school. And I think it went from one out of 259 to fourteen a year later or two years later, right?

So now what exactly. Because you made a very clear point that even if you did this Black student application program, the academic rigors were the same. So what did the program do? What was the goal?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

So the goal in a nutshell was to increase the number of Black applicants applying into the MD stream at the University of Toronto. And what it aimed to do was to ameliorate some of the biases that were inherent within the application program system.

And so what they did is that they required that the applicant write an additional essay. So the way that U of T usually works for its stream to apply to medical school is that it requires you to write a series of short essays. About eight was what I had to write when I applied to medical school.

And so for this stream, they required you to answer an additional question. Now I'm unsure if that exact question has changed over the years. But what it was back then, which is, why did you feel it was important for you to apply through this Black student application stream, and how is it that your identity may impact your medical training? And things such as that.

And that was incorporated, but then it was also incorporated that a Black file reviewer or a member of the Black community, Black academic community, Black medical community would be involved in reviewing your application as well as the actual interviewing process.

Now, that was very different for me, because when I was in the process of applying to medical school, I actually vividly remember the day of my U of T medical interview, which I talk about, I write about in the book. Where I enter, and it's just a sea of medical school candidates. And of course, the anxiety and the sweat is palpable in the air.

And I walk in and there's no other Black applicants. There were no Black invigilators. There were no Black interviewers either as you went from station to station. And there's about four stations, twelve minutes per station.

And so when you're going into these spaces and nobody looks like you, you're naturally going to just be aware of that. At least for myself, I was naturally attuned to that, especially having been in so many places before where I was the only Black student.

And so what a difference it makes to actually be able to alleviate some of the implicit bias that can be present within this system. And that's what the Black student application program aimed to do and continues to do, and has made a significant impact in the educational environment. Not just for the Black students, but for all students. The diversity of thought, the diversity of lived experience, the diversity of culture enriches the educational and the medical educational environment for everyone.

Guy Kawasaki:

And do you think that some of the students are still thinking, "This is a Black student, so it was less academically rigorous. There's a quota system, it's unfair, it's reverse discrimination." Do you think that still happens there?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

I am sure that there are individuals who may question whether or not another Black student had merited their spot. I think that is, again, a vestige of racism. And I know that as I was in medical school, I was fielding that remark constantly, constant questioning.

Even on my very first day of medical school, day one, just the morning before my stethoscope ceremony, someone asking me, "Did they make it easier for you to get in here? Did you need lower grades? You're the only Black student, so did they do something to make it easier for you?" That was before BSAP was even instituted.

And so I am sure that there may be individuals out there who are thinking these thoughts, feeling these thoughts, because these are the thoughts that have pre-existed the BSAP program.

However, I can assure you that intelligence, the tenacity, the ambition of these students, of these Black students going through, it will rival any other student who was there. Any other student.

And I just actually gave the convocation keynote for the class of 2024, and this was the largest class of Black medical students in Canadian history that came into the University of Toronto. And they had just graduated this past year. And guess what, the number two student out of the 260 students, that got the second-highest grades across all four years was a Black woman.

And I think that stands as a brilliant example of the fact that we are not diluting the collective intelligence of the class now. These are the students who we would have lost to the American schools. And this is true.

Actually when I was doing my first year of mentorship for the BSAP program, so when I was still a second year medical student talking to these other students, encouraging them to apply through BSAP, many of them were saying, "I got a scholarship to Yale. I have a scholarship to Northwestern. I have a scholarship to these places in the States," that have already been doing these kinds of programs and systems encouraging Black medical students to apply or Black students to apply to their medical school.

So we were going to lose them. When in fact, now we are retaining them. We are retaining this talent, the brain drain. We're slowing it down. And so I don't agree at all with anyone who questions the intelligence of Black medical students.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, just to set the record straight, didn't you become the valedictorian of your class?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

I was elected. I was selected by my class to be the valedictorian of my class. And that is an honor that I wear with so much incredible pride and responsibility. And I write about this in the book as well, because it was almost ironic because in literal definition, the valedictorian is supposed to reflect the class. So it was ironic because I was so different from the rest of the class.

I think that it speaks and that my being selected speaks to the transcendence of the work that I was trying to accomplish, the transcendence of who it is that I am and what I embody, which is truly embracing your audaciously authentic spirit, embracing what it means to be a physician, what it means to be an astute medical student, someone who genuinely cares for other individuals.

These things are transcendent. And I'm really so grateful that my class appreciated that and saw that, and that I was able to have that incredible opportunity.

Guy Kawasaki:

Speaking of transcendent, I am asking you now to tell the story of your interview. And when you were in the interview, and you're prepared for every possible question, except when you opened the door and told the interviewer that you participate in slam poetry and he asked you to recite a poem. I must say I've never heard of that in any application interview, so please tell that story.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Absolutely. I feel like most people can relate to that experience when you're entering into an interview. And certainly if you're interviewing for a professional school like medicine, these interviews, you feel like you have spent your entire life working towards this one moment that feels so decisive for the trajectory of the rest of your life.

And so through militant fashion, in the weeks preceding this interview, I had done an archeological dig throughout my entire life. And I literally had a notebook that was very thick. And it was highlighted, it had every single detail down to what was going to make me a brilliant medical student and a brilliant doctor thereafter.

And so when I was in that interview room and we had spent, it's about twelve minutes per room. And we had spent maybe eight or so minutes going through my resume talking about all the different things, my research, and my extracurriculars, and everything.

And we had a couple minutes left and I thought, "Okay, now's the chance for me in regular interviews to then turn the tables a little bit and ask him some questions about the University of Toronto and what it's like to be a medical student, what it's like research within the institution."

And so when I thought it was my turn to start asking some questions, and then he looks at the final line in my resume, and he saw that I'd recently competed at The Canadian Festival of Spoken Word and was nationally ranked. I placed as one of the finalists with my team, the Hamilton Youth Poets. And so he looked at it and he said, "Oh, you're a performance poet. Interesting. So I'm in the company of a nationally ranked poet. Why don't you perform something for me?"

And in that moment, the sheer terror that just blitzed through my body up my spine, I was like, "Oh my gosh." I had not rehearsed a poem in several months. That was the end of January was that interview. And I had not competed or been on a stage since October of the previous year. And I'd actually put myself into semi-retirement because it was so exhausting preparing for nationals, that I did not want to do any poetry at all in the interval.

And so in that moment, I had to make a quick calculation of, am I going to share a poem? I knew, I had my entire repertoire of poems memorized. You have to do that if you're going to be a professional poet. So I knew that I could execute it. I just had to think quickly, what poem would he want me to share? And he said, "Do your best poem." And immediately I thought of my poem “Skin”, which talks about my experiences of being in my skin as a Black woman and navigating the world in my Blackness, and in my femininity, and all the different things.

And the interviewer was a senior white male cardiologist at the University of Toronto. At least on the surface, very different from me with regard to all of those different aspects.

And so I didn't know if this was going to land with him. I had no idea what his political inclinations were. I had no idea what his value systems. I had no idea. But in that moment, I decided to take what I now call an audaciously authentic stance, and I was going to share it.

So in that moment, I shared with him, "My skin is like dark ebony under the blazing sun. Won't you tell me that I'm beautiful, and don't preface it by telling me the limiting conditions of my beauty." And I remember thinking after I gave him about probably a minute or so of that poem, pausing when the bell rang out. And it was just me and him, and I came back into my body.

And it was just this moment of horror of looking at him like, "Oh my goodness, I can't believe I just said all of that to you. Did I completely blow my medical dreams and medical ambitions?" And he was like, "That was amazing. I want to listen to the rest of it." And it was the biggest exhale of relief I've ever done in my entire life, my whole life.

Guy Kawasaki:

And did you call your mom or your sister and say, "Guess what I just did in my interview? I had to recite ‘Skin’," or whatever.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

I called my mom because my mom was waiting with bated breath to see how my interview had gone. And so I called her and I said, "Mommy, I got to perform in my interview." And she's like, "Perform, why were you performing?" "He asked me to perform my poem, and so I performed it and he loved it. And I think that might've been my ticket into medical school." I don't know how it is.

But I think if anything, it was incredibly symbolic. Because I always say that being a better poet, a lifetime of being a poet, a writer has been the best preparation for me to be a doctor. And so I just think it was very symbolic that in my medical school interview, the most decisive moment of my life, he asked me to perform poetry.

Guy Kawasaki:

So back up a second and tell me, what does being a poet have to do with being a doctor? Why is that a prep for you?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

It is everything. The two are so interdigitated for me. And that's because at the basis of being a good doctor and at the basis of being a good poet is about being a good human. It's about holding tight to your humanity.

And what poetry, what a lifetime of poetry has taught me to do is to have this unflinching examination of the human experience. That's what poets do. We always hear about the tortured poet, the sad poet, the tortured creative. And that's because poets analyze the world. All parts of the world, even the parts that make us feel heartbroken, the parts that are devastating. That's typically where we get the best poetry. And we have to be able to do that unflinching examination.

And then on the flip side, when it comes to being a physician, what it requires of us, especially within psychiatry, is being able to sit in some of the most heartbreaking, devastating, unbelievable situations. Holding people's hands through the darkest hours of their lives and being able to sit with them in that, to guide them through that, to be able to continue with our critical and analytical mind throughout these kinds of situations.

And so I think that poetry has been this beautiful transference of that. But then also at the same time, being a performance poet on top of that. Taking my poetry and then giving it to the world, that in and of itself is an act of transcendence that has enabled me to be able to connect with other individuals. To have conversations, much like in my medical school interview that might be difficult to have otherwise. Some of the hardest things I've ever shared with the world, I could only do through poetry.

And so that again, has enabled me to build this ability, to not only be compassionate, but to be vulnerable. And I take these skills and I translate them to my role as a doctor. And I truly believe that's what has enabled me to be the best doctor that I could be.

Guy Kawasaki:

So hundreds of girls are going to be listening to this podcast. I'm going to say I'm going to study poetry so I can be a doctor.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

I love that. I love that. Step one, be an amazing poet. And then step two, be a doctor.

Guy Kawasaki:

So I have to ask you a question that I have not asked any other guest, and we've had about 260 guests. Which is, how does one become a Barbie role model? I just need to know that just in case they call. So how do you do that?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

It was really interesting because I got the email from Barbie. Well, through my then agent. I was running around the hospital and I was actually a few months pregnant, and then I got the email that they wanted to make a Barbie out of me for Barbie role model. And I'm still stammering because it still seems so surreal.

I'll never forget being in the hospital and seeing the title, the subject line of that email and thinking, "There is no way that this is real." And then realizing that no, it actually very much was real. And then going through the process.

So the Barbie Mattel Canada, they've gone through their very extensive vetting system in determining who would be the right candidates. And I was selected to represent Canada for their Healthcare Heroes campaign. And so this was in 2021, and they had selected six women around the world to be Barbie role models and to have Barbies made after them. And I was selected to represent Canada.

And so I went through the process with Mattel to actually create various prototypes of what I wanted my Barbie to look like. So I was very involved in the actual creation of it and going through different iterations. And I sent them different pictures of me with different hairstyles, different angles. It was really cool to see the behind the scenes.

And then as they continued to tweak and create different versions of the Barbie until it was just right, and then being able to unbox it and actually see it in the flesh on national TV, it was just the most surreal experience. It still doesn't feel like it actually happens. And whenever people tell me, "You have a Barbie," I'm like, "Oh my gosh, I do have a Barbie." It's the most incredible thing though.

Guy Kawasaki:

I have to say that getting a Barbie doll may be more prestigious than a MacArthur Fellowship, I'd have to think about that. Although I don't think you got paid a million dollars to be a Barbie role model. Is your doll still current? Can somebody go to barbie.com and order the Chika doll?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

I wish. So it's actually one of a kind Barbie doll. So I have the only Chika Stacy Oriuwa. I know. And I've been asked in the last three years by hundreds if not thousands of people, "Where can I get this Barbie?" So Barbie actually does have a Black female doctor that they do sell.

Guy Kawasaki:

It's not you.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

But no, it's not my Barbie. I know, and it makes me so sad. I wish I could give out more of the Barbie doll that I have. It's incredible. But for now, it'll be played with by my son and my daughter, and hopefully they don't pull her head off and torture her.

Guy Kawasaki:

It's like getting an Olympic gold medal, right? We've had Olympic gold medalists on this podcast. And they often tell me, "I don't even know where it is. I think it's in my drawer, or is it in the bathroom?" And, "Brandi Chastain, where's your Olympic gold medal?" "I don't really know."

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

I definitely know where she is, because my husband who is far more, not that he's more proud of my accomplishments, but he is really proud of my accomplishments. And so he has encased the Barbie in this glass cylindrical casing and has put her inside of another glass case.

And so she is displayed within our kids' playroom, so I will always know where she is. But yeah, that is something that for me, I guess you could say that's my Olympic gold medal is my Barbie doll.

Guy Kawasaki:

And when you get selected, do you have to go on a national tour? Is it like being Miss America or something? What do you have to do?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

So it was interesting because this was also during the pandemic. This was, when I received the Barbie, it was August, early August of 2021. So I don't know if things would've been different if it wasn't right in the thick of things. And I was also five months pregnant when I received the Barbie.

And so luckily, I went to a few news stations. And because I'm in Toronto, everything was broadcasted nationally from Toronto. And then a whole blitz of media came to my home, which I felt very fortunate for being five months pregnant and just being able to walk down the stairs and oh, the media's here. I don't have to go too far.

But it was an incredible experience. And so it was definitely cross country, and then also international because I got to do some bigger media and reach out to different countries. And so people from all over the world were hearing this story, and that was a really phenomenal experience.

Guy Kawasaki:

So in the final model of this doll, how was your hair styled?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

So I wanted to ensure that the Barbie was as authentic as I was and that she had a big, beautiful Afro, Afro-textured Afro, and I wanted to ensure that it was as booming and voluminous as possible. And so if you look at the Barbie, it's three times the size of the Barbie's head, which is hilarious. And when I do have my Afro out, my Afro really is quite voluminous and beautiful. And so I wanted to ensure that the Barbie was a reflection of that, and it certainly was.

Guy Kawasaki:

I love that. If you think about it, and if you can remember, please send us a picture of that Barbie doll so we can use it when we promote this episode. This is such a great story.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Absolutely. I can send you the official Barbie photo. I'll be happy to do that.

Guy Kawasaki:

So someday if they make a Barbie doll out of Madisun, we'll be fully prepared to know what to do.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Yes. I could show her the Barbie ropes, the plastic. I could show her all of that.

Guy Kawasaki:

I have one really serious question and then I have one more question. And you'll be done with me and you can go back to saving lives and writing poetry. So the serious question is, you talk about a time where the students had to have a debate about the moral issues of medical assistance in dying for the mentally ill. And I would love to hear what you have to say about that having practiced psychiatry. Should the mentally ill have the access to medical assistance in dying?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

So that is a very serious question for sure. And I wrote about this in the book as you mentioned, and this was actually for my residency interview day. We had to write about this.

And I shared in the book an experience. Now this character is fictionalized to protect patient confidentiality. But I share about the experience of a woman who I had met, who had faced a lifetime of serious treatment resistant mental illness, such that the point in which they perceived their life was no longer one that was sustainable.

And I wrote about that experience when I talked about this question that we were posed with, whether or not someone with mental illness should be granted access to MAID. And in that stance I talk about if we want to treat mental health as serious and as potentially devastating as ailments within physical health, then does it not require us as physicians to then realize that there can be mental illnesses that reach a point that are beyond treatment?

And at what point do we recognize our responsibility as doctors is not always ultimately to extend a life, but to actually protect the sanctity and the dignity of the individual who is experiencing this illness?

And I say all of that to say that I guess my stance is still relatively unchanged from then, because I know that the debate is so incredibly heated, and that I do have that appreciation for patients, and for families, and for individuals who do believe, and can see, and have that perspective, that there is a point where mental illness cannot be treated, and there is a point where the suffering of what it is that they're experiencing should not be continued.

And so I can appreciate that perspective. And then I can also see the ways in which as psychiatry, that the field of psychiatry, as a psychiatry resident, as a future psychiatrist, also the argument that it is our job continue to extend the life of individuals. It's our job to continue to try and always improve the mental illness of certain individuals. That it might be a fleeting moment in which you believe your life is no longer worth living, but can we potentially explore other options?

And so I say all of that to say that I don't know if I've necessarily landed on a concrete answer, but it is something that I do reflect on and have reflected on very deeply for a long time.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. I lied. I actually have one more question after my final question. So my final question, and I want you to talk about your book and all that stuff. But pretend that you are addressing young girls and they're listening to this podcast, and just give them the best advice that you can based on your life experiences.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

I love this question. What I would say to them is to never forget the power of your voice and to use it. Even if your voice shakes, even if it's a whisper, to never forget the power of your voice, and that you get to define who it is that you are, the strength that you possess, the journey that you are on. And not to let anyone else grab the pen from your hand and write the story of your life. You will always be the author.

And so to continue on that journey is so incredibly important. And it starts with recognizing the beauty of what your voice is. So that's the message I would love to relate to any young woman listening to this podcast.

Guy Kawasaki:

My God, you are just a fountain of poetry. I could ask you, what time is it in Toronto? And it would come out as a poem? Oh my God. Geez. Okay, I promise you this is the last thing. This is the last thing. So we interview about fifty-two people a year. So we've done this for about five years. So we've interviewed 250, 260 people. I've read a lot of books, I've seen a lot of videos.

But you had a line in one of your videos and I want to hear you say it now. I sure hope you remember this line because it was so memorable to me. I hope you can remember it. But I'll give you the gist of the line. The gist of the line is that, "No need to reply, my hope is only to edify." And I thought, oh my God, that is such a great statement. So as the last thing you do for us, could you just say that line, that stanza. I hope you have it memorized.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Yes, do. It's actually from my poem, “Love Letters From My Body”, which was a very vulnerable and raw exploration of my experience with disordered eating from the ages of nineteen to about twenty-three. And I talk about that once again in the book, but this poem explores that. And so the stanza is from that. So I can absolutely recite that line and maybe a line or two after that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Think of this as your medical interview.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

It really is.

Guy Kawasaki:

And I'm asking you perform.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Yes. Okay. "Dear Chika," she wrote, "No need to reply. My hope is only to edify the wonders that you are. When you search for meeting amidst the twilight stars, I hope you know that the answers were always at your fingertips. You were equipped with a mind that could steer ships, lips that could part the seas. Promise me that you'll never forget that you're nothing short of a miracle. And when you move your feet, it is lyrical. So keep dancing like no one is watching. And if you feel the need to syncopate your joy, I will deploy a series of letters scented with lilac, written in gold, detailing the light that you hold for me, to you, to us. Trust that all you need to do is listen to this body.”

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh my God. Holy shit. That's why you're a Barbie doll, and I'm not my God. Among other reasons. But yeah, that was just remarkable. Chika, thank you so much for being on our podcast. And you definitely have brought a great deal of joy, and light, and laughter to me today, and I'm sure everybody listening to this. So thank you so much. Oh, just tell us the name of your book because we want people to read your book. I read it and I loved it.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Oh, thank you. And I just want to say that it has been an absolute joy and pleasure to speak with you today. And my book is called, Unlike the Rest: A Doctor's Story by Me, Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa. And it is available wherever books are sold and also at your favorite online retailer.

Guy Kawasaki:

See, even your sales job is a poet. My God, I'm going to have you do marketing for me and my books.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Oh, I would love that.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm going to get you and Lovey, and I'm going to own the Nigerian market.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

If you could introduce me to Lovey, that would be the coolest day ever.

Guy Kawasaki:

Listen, like I said. I only know two Nigerians, you and Lovey. And based on that rather statistically invalid sample, oh my God.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

I will say we are pretty cool people. We're pretty remarkable people. And your sample size, although very small.

Guy Kawasaki:

And Jon M. Chu, if you're listening to this and you make a movie called Crazy Rich Nigerians, you credit me for that idea. Okay?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Absolutely.

Guy Kawasaki:

All right, so this has been Remarkable People. I'm Guy Kawasaki. I hope you enjoyed this episode as much as I did, and you learn about racism, and dealing racism, and reducing racism, and hopefully eliminating racism. And if you're a patient and you see a Black woman come in to treat your room, you should thank your lucky stars that that's the doctor. That's clearly what I learned today.

So I just want to thank the rest of the Remarkable People crew. That is of course, the remarkable Madisun Nuismer, producer and co-author Jeff Sieh and Shannon Hernandez and who are doing all our sound design. And finally, Tessa Nuismer, our ace researcher who helped me find all these great questions for Chika.

And now we're going to let you go, and we're going to let you go to your kids, and your husband, and your patients, and your poems, and all that. And congratulations for a life well lived. And you're so young, oh my God. Someday when you're a Prime Minister or whatever it is of Canada, you remember me. Okay?

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Thank you Guy.

Guy Kawasaki:

We'll go to Tim Hortons and have breakfast.

Dr. Chika Stacy Oriuwa:

Yes, I'll treat you to a breakfast better than Tim Hortons. But yes, I will treat you.

Guy Kawasaki:

All right, take care. Bye-bye.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply