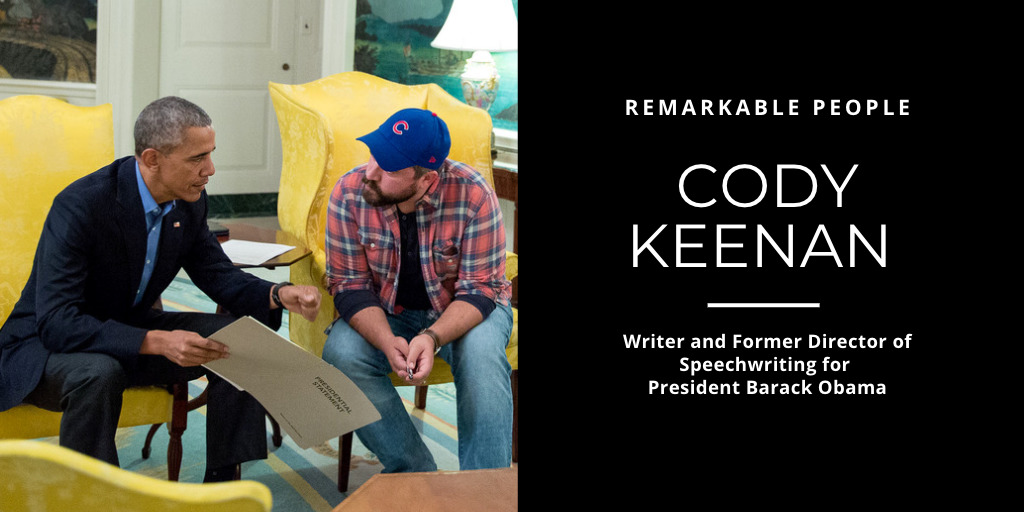

Cody Keenan was President Barack Obama’s director of speechwriting from 2013 to 2016.

He has a degree in political science from Northwestern University. After graduation, he worked as an unpaid intern in Ted Kennedy’s office. Then he got a master’s in public policy from Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government.

In 2008, he worked in the Obama presidential campaign. He began his work in the White House as a presidential speechwriter in 2009. His next position there was special assistant to the President and deputy director of speechwriting. Then in 2013, he became an assistant to the President and the director of speechwriting.

In our interview, he describes what must have been a challenging job because so many constituencies want to provide feedback and suggestions in the president’s speeches.

He is currently a partner at Fenway, a speechwriting and strategic communications firm. He is also a visiting professor at Northwestern. Take a look at his LinkedIn profile: the cover photo says “One voice can change the world.”

Listen to Cody Keenan on Remarkable People:

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please head over to Apple Podcasts, leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Join me for the Behind the Podcast show sponsored by my friends at Restream at 10 am PT. Make sure to hit “set reminder.” 🔔

Text me at 1-831-609-0628 or click here to join my extended “ohana” (Hawaiian for family). The goal is to foster interaction about the things that are important to me and are hopefully important to you too! I’ll be sending you texts for new podcasts, live streams, and other exclusive ohana content.

Please do me a favor and share this episode by texting or emailing it to a few people, I’m trying to grow my podcast and this will help more people find it.

Loved this podcast on #remarkablepeople with speechwriter Cody Keenan! 🎧 Share on XI'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. This episode's guest is Cody Keenan. Guy Kawasaki: Because you have been the architect of such great speeches. I want to know how you do your best and deepest thinking. What conditions, what tools, what, whatever.

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Cody was Barack Obama's director of speech writing from 2013 to 2016. Imagine what it must've been like to write speeches for Barack Obama. Actually, you don't have to imagine. He's going to explain it in this episode.

He has a degree in political science from Northwestern University. After graduation, he worked as an unpaid intern in Ted Kennedy's office. Then he got a master's in public policy from Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government.

In 2008, he worked in the Obama presidential campaign. He began his work in the White House as a presidential speech writer in 2009. His next position was special assistant to the President and deputy director of speech writing. Then in 2013, he became an assistant to the President and the director of speech writing.

He's currently a partner at Fenway, a speech writing and strategic communications firm. He's also a visiting professor at Northwestern. By the way, take a look at his LinkedIn profile. The cover photo says it all: "One voice can change the world."

In addition to taking you inside the Obama White House, Cody provides a liberal dose, no pun intended, of speaking and speech writing tips.

I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People, and now, here is Cody Keenan.

Guy Kawasaki: Tell us about this adventure working as an intern in Ted Kennedy's mailroom. How'd you get that job? What'd you learn?

Cody Keenan: I often tell my students now and young people that your first job is actually your best education, you just don't know that at the time. I went to Northwestern University, graduated, moved to Washington hoping to get into politics, and it was a real struggle just to get that first job. I didn't have any connections in town.

I knew one person, a fraternity brother of mine who was in Teach for America. So he was useful in that he let me live with him, and now he's one of my best friends, but not so much in finding a job. And I just wasn't prepared to find a job.

I went in there thinking I was hot stuff because I went to a good school, Northwestern University. I'd seen every episode of the West Wing, right? How hard can this be?

Guy Kawasaki: Yeah!

Cody Keenan: It turns out, everybody went to good schools and nobody cares that you have a political science degree and they just want to know what you can do, and the answer was: not much. I could talk to you about political theory or write a good paper, but what people are looking for at entry level is: what are your skills?

And I didn't have many. So after a bunch of failed interviews, I finally landed an unpaid internship in Ted Kennedy's mailroom which was an incredible stroke of luck. Getting that unpaid job was better than a lot of the paid jobs I was going for.

And it was fortunate that I had parents who could help cover the rent and subsidize me as I was starting out, so privilege is no small part of that, but that job, doing the most menial of tasks, getting people sandwiches, running letters around Capitol Hill, which also infuses you with this sense of awe--just being asked to run a piece of paper across the Capitol for a twenty-two-year-old feels like this monumental task and you're passing all these great, historical figures, and it's cool.

But the most important learning experience was opening these letters from people to figure out where they need to go, which staffers need to see them. And I hadn't thought of politics at that point yet in my life as it's really just people need help and what can you do to just make things a little bit better.

And it was really surprising how perfect strangers would kind of spill their guts on the page like that, so one of the things Senator Kennedy prided himself on was constituent affairs. And it's like, if you had a problem and you lived in Massachusetts, we're going to solve it for you.

But it was also just fascinating to see how people describe their everyday lives. A lot of times they just want it to know that someone's listening. Each letter was sort of an act of hope in a way. You're hoping that somebody on the other end is going to read this letter and care.

And that's the type of thing that has sort of infused my career working for Barack Obama along the way, and that's what would go into our speeches. I'm probably skipping way ahead, but he, in The White House, wanted to get ten letters a day from who we called “Real people,” and we meant that as a compliment. They are people who are not involved in politics. As speech writers, we would read those too, and we would write our speeches with an eye towards the way that people were talking about the challenges in their lives.

And just a really well-written letter from somebody, from a quote-unquote “Real person,” was more valuable to me than any polling data.

Guy Kawasaki: Are you telling me that a letter sent to the White House really gets read by human? Every letter?

Cody Keenan: Every single one, yeah. We had a big correspondence team. I want to say it was like thirty full-time staff, and then usually twenty to fifty volunteers a day. And people really did volunteer. A lot of retirees would volunteer to come and read mail. So somebody's always read it.

Guy Kawasaki: Really?

Cody Keenan: Yeah, and ten made their way to the president's desk every night. He was adamant. He wrote about this in his book, but he was adamant about getting a representative sample, “I don't want just ten letters that blow smoke. I want letters from people who are pissed about things or who were grateful that something changed their life in a way I didn't intend it to.”

And every once in a while, they'd throw in a letter from a kid that was always just great comedy and kids would draw pictures, and it was usually the tenth letter to just really put him in a mood.

Guy Kawasaki: That's great. So can you talk about the process of writing a speech for Barack Obama? I can't even wrap my mind around that. How does that happen?

Cody Keenan: It's terrifying. He's an intimidating writer in his own right, and editor. And one of the added obstacles of writing for him is that the first part of the process is you panic a little bit because you want to make sure you're getting him something that he'll be pleased with.

The part of it is you want to impress him as your boss and as a person. There are four broad buckets of speeches. There are your everyday message events, a ten to fifteen-minute speech on the economy or healthcare or education. It's what you want to use your bully pulpit for, to drive news coverage of.

There are more ceremonial speeches, like, commencements, eulogies, Medals of Freedom, something where you can actually kind of use some beautiful language and get into beautiful ideas and have fun as a writer.

There's a political stump speech where it's basically the same speech a few times a day, every day, when you're running on a campaign or pushing a certain issue that the speaker can internalize and almost memorize to a point, and you update it every day with daily news. And those are probably the most fun because when you're on a political campaign, you finally have a foil as part of your writing.

And the final one is something like the State of the Union Address, a major policy Address that just...it's sucks. It's such a beast to put together and really, really awful. So all that is to answer questions, but there's no one way of doing it.

But with a speech that he really cares about, if there's kind of a big one coming up, we usually sit down with him on the front end, and he always made time for his speech writers because he views speech writing as a valuable craft.

It's a way to simply put, “think before you speak.” It's the opposite of tweeting. You're taking the time to craft an argument--a logical, linear argument with supporting information and incorporating other people's viewpoints or going after their viewpoints.

But it really is just thinking before you speak, and he's somebody who views complexity in situations. To be president of The United States, you're dealing with complex issues all the time, and he always trusted voters to absorb that complexity. That's why a lot of his speeches were so long, but so all that to say he would always make time for his speech writers.

And we would sit down on the front end of a big speech and say, "What's the story we want to tell?" And he would just talk out loud for a while and we'd furiously type. We call that part, “the download,” and then we might have, by the end of the meeting, a couple of pages of stream of thought consciousness, and then it's on us to put a structure around that and call up the policy people in the White House; put some meat on the bones of it.

Ask our researcher to find some really interesting stories or anecdotes, whether historical or local. If he's going to go visit some city, “Give me a few really interesting numbers that are sticky and memorable for the audience.”

And then the fun part is you actually get to sit down and start writing and creating something and you kind of let creativity flow. That's when it's at its best. I mean, there are plenty of times where it's hard to do that when he's giving ten to fifteen speeches a week, and you've got meetings and then something unexpected in the world happens.

Nothing--it was never as easy as, “We just sit down in front of our computer for eight hours uninterrupted.” So I do a lot of writing at night because things finally quiet down and your brain can get a little bit bigger and write a draft. And then before we'd send it back to him, we'd usually send it around to a few dozen people at the White House, just to look it over, whether it's policy people to make sure the policy is correct.

The communications team to get their steer on, whether or not we're hitting the right message. The lawyers to make sure he's not saying anything illegal, an army of fact-checkers, including the woman who became my wife, who would just tear the speech apart and say, "This is wrong,” "This is an accurate," "This is off." And then, ultimately, we'd send it to the president, usually the night before. If it's a really big speech, maybe a few nights before, and he would work on it also late at night.

He'd usually start working on a speech after the first lady and his daughters had gone to sleep, and we could expect an email from him around three in the morning, telling us that he'd finished, whether he liked it or not, if he wanted to do something more, and then we'd go in around seven AM and pick up his edits from the residents and start plugging them in.

Guy Kawasaki: Let's take the most interesting or scary case which is State of the Union. So for a one hour State of the Union, how many person hours went into speech writing?

Cody Keenan: For just me or for everybody who was involved?

Guy Kawasaki: Everybody.

Cody Keenan: Boy, thousands because you start months in advance. We'd usually have a point person inside the west wing who would run point on the policy that goes in the State of the Union address because the State of the Union Address is the president's biggest audience of the year, and it always comes early in the year in January.

So this is your chance to set the agenda for Washington, for the media, for the country, and sometimes for the world if you're ambitious enough. And so everyone in the federal government wants their ideas included in the speech, which would make it days long. So we would have somebody running a policy process.

Fortunately, not us as speech writers and kind of solicit ideas, maybe three to four months in advance from every cabinet agency, “Give us your best. Don't give me 500 pages of everything you're going to do this year.” In tandem with that, we would actually put a poll in the field, polling some of these ideas for their popularity.

Now that doesn't mean we would choose the top twenty, but it would help us decide what not to put in there sometimes. Like I remember one year, for example, the treasury secretary, Jack Lew, wanted to abolish the penny, and he wanted the president to mention that in the State of the Union Address.

And that pulled 100 out of 100 ideas. Seven percent of Americans wanted to abolish the penny. So having that poll was helpful in that I could say, “Look, Mr. Secretary, we're not going to do this. At least not in this speech, but you can go nuts and do it if you want."

Guy Kawasaki: That would have been more controversial than gun control!

Cody Keenan: Yeah. So we'd have this big binder of policy ideas the president would go through, and we'd know what the big ones were. We didn't have to talk to anybody to know that you're going to talk about certain economic issues, healthcare, whatnot, but the president would give us ideas too that he wants in there.

And our first meeting with him, this was a unique speech where we would do--we probably sit down with him about a month in advance, and we do what we call the “blue-sky meeting.” We're at 50,000 feet, flying over the country. Congress doesn't exist. Political realities don't exist. You can do anything you want, what are we going to do?

And that's always a really fun exercise. And then the sad exercises week later when it's like, “All right, we're down at 20,000 feet now, and things are a little more real, what can we do?” Until you finally get a little more granular, and then I'd finally just kind of shut myself away for a week.

And I was the lead writer on his second four. John Favreau was lead writer on his first four. I just kind of shut myself away for a week and try to get, by this point, we've got about seventy ideas that are going to go into the speech, and what is a way that I can structure them so that they still tell a story so that it's not just saying, “Okay, first this. Second, that. Sixty-five, we're going to do this. Sixty-six…”

How do you bundle them all together in a way that makes sense to the listener? And we can get into this too, but a speech is meant to be listened to or watched and not read. So once I kind of get that into a story, I would go to my team. I had this fabulous team of writers at the White House who were just so smart, often better than me, and just looking at each other's work made it better.

So I'd asked my speech writers for their input and their edits on it, and this speech I'd usually, actually, subvert the process and I'd send it to the president before I sent it to policy teams. Look, having an entire week for seventy people to go over your speech is a recipe for a heart attack, or at least a breakdown of some sort.

So I'd give it to the president and see what he thought. Whether he thinks we're on the right track or not. If he thinks we're on the right track, then I'd send it to everybody else. If not, I'm going to go spend a night rewriting it, and then I'll maybe send it around to everybody else. So the State of the Union really is a unique speech, and it's awful.

It's one of those speeches that every speech writer dreams of being able to write, and then once you've done it, you'd never want to do it again because it's such a beast and it's got so much buildup in Washington, and there's all this pomp and circumstance and tradition around it. And that's why tens of millions of people still tune in and even if the audience gets smaller and smaller every single year.

But then a day later, nobody cares or remembers what you did. Now, it does give direction to the federal government, to agencies. You can use the bully pulpit to ask mayors and governors to pursue certain policies, to ask corporations to pursue certain policies, to ask the American people to take certain actions and do certain things and to send guidance to the rest of the world.

All that stuff matters and lingers, and if you write a good enough State of the Union Address, you can actually run with that message for a few months. And every time you give a policy speech, make sure it ties right back to what the president said in January. If not, you just kind of abandon it and just keep on trucking.

Guy Kawasaki: I haven't heard you mentioned the “R” word, which is rehearsals. How much rehearsal is there?

Cody Keenan: Rehearsal is super important, and any speaker shouldn't feel nervous about it. You should spend that time to really knock a speech out of the park. There's no shame in speech coaching or practice.

For the president, by the time he was in the White House, he had given thousands of speeches and he was very confident in his own ability to give a good speech.

And he would tell us how good he was at giving speeches and writing speeches. He would remind us all the time. He has publicly said he's a better speech writer than his speech writers. He would remind us all the time that he wrote that 2004 Boston speech by himself, and every single time it'd be like, “I know. I've heard that before. It's amazing.”

But even he still practices. So for pretty much only for kind of big moments of national importance. So we would, in the map room of the White House, which is on the ground floor of the residence, right next to the room where he usually exits to get on Marine One, we would set up a full-size podium and the teleprompter just the way he likes it.

I put the speech in there and then a few speech writers, maybe the communications director, press secretary, a few of us would go in there and just watch him speak and maybe take some notes. As a speech writer, I would listen to how the speech is coming off and I'd say, “All right, that sentence was a mouthful. Let me see if I can break that into two or shorten it a little. That sentence might need an extra syllable. I'm going to build in a pause here and do a hard return and start a new paragraph,” and he would notice that too. He might stop, be like, “Hey, Cody, let's break that up.”

Without an audience applauding, and the State of the Union Address, the applause is the worst because you've got people standing up and down in between every sentence. The speech would usually last about twenty-five, thirty minutes, but he'd do one quick run-through, ask for our feedback. If there was a section that he really wanted to get right, maybe a big emotional ending or whatnot, he might practice that again and that's it.

He would just do that one run through. I'd race back to my desk to make some last-second changes. He would go have--his tradition was he would go have--it's kind of like his game day prep--he'd go have dinner with the First Lady and his daughters, get ready, put on the right tie that he'd picked out for the occasion, and in the motorcade over to the Capitol, he'd listened to Eminem's Lose Yourself.

Guy Kawasaki: Let me get this straight. You're telling me that he spends only about an hour rehearsing the State of the Union?

Cody Keenan: Unless he does it in secret when we're not around. Yes.

Guy Kawasaki: Wow. Wow.

Cody Keenan: Part of the reason why he can get away with that is he really is a speech writer and a very detailed editor. So for the State of the Union Address, he’ll have scenes six drafts, one each night before the speech, and he works on them. He gets in there, he makes edits, he moves things around and it's to the point where by the time--that's actually why we use a teleprompter!

By the time we load it in the teleprompter, it is exactly what he wants to say with every word exactly where he wants it. I'm not comparing State of the Union Address to a piece of music, but it's like a piece of music in that everything is exactly how he wants it to be. So part of that is why he only has to rehearse once because, by that point, he's already been through it several times and it's what he wants to say.

Guy Kawasaki: My issue with what you just said is that thousands of people are going to listen to this and say, "Oh shit, I don't need to rehearse! I'll just rise to the occasion like Barack Obama." The problem is you're not Barack Obama, nor are you Steve jobs. So you got to rehearse.

Cody Keenan: You need to rehearse. You need to rehearse. He’s--I mean, once you've done it thousands of times to, I think his biggest audience in person was 250,000 people--there were a couple on the campaign that were over a hundred thousand--once you've done that, you probably don't need to rehearse as much.

We had some pretty strict ethics rules inside the White House on what else we could do in our spare time, but since leaving the White House, I’ve spoken at universities, corporations, other countries, and I think only now am I starting to get pretty decent at it in four years into it. But in the beginning, I had stage fright. I was terrified. Like I said, there's a reason why I'm a writer, not a speaker.

After I gave my first speech, I came back to the office, and this is after the White House but President Obama and I still shared an office with a few other staffers, and I told him what I realized once I got up there is I didn't know what to do with my hands.

And now, all I can think about for the entire speech is, “Oh my God! What am I doing with my hands? Should I hold them up here? Should I put them in my pockets?” And he said, "Don't put them in your pockets because then you slouch and hunch back a little bit." And I was like, "Well, okay. Well, I put them in my pockets for the entire speech, but I won't do that."

Well, I teach speech writing now, too, and what I tell my students and people who need speech coaching is, actually, just watch a few videos of people speaking, people whom you admire. So if it's President Obama, watch him give a few speeches and watch what he does with his hands and his body language, and you can try to emulate that in the beginning until you start to feel comfortable with your own body. So I now know what to do with my hands.

Guy Kawasaki: Is that a siren? Is that on your end? It's not on my end.

Cody Keenan: It is. I'm coming to you live from downtown Manhattan, so…

Guy Kawasaki: This is a real miscellaneous question, but that three-ring binder in front of him, is that just in case the teleprompter goes down?

Cody Keenan: That's exactly what it is. That's exactly what it is, and it's happened before. So that's an added trick during the speech.

Every once in a while, he'll make sure to keep turning it. Like when the audience is applauding, he'll look down and turn the page to where it needs to be just in case the prompter goes down.

Guy Kawasaki: Now I'm going to semi-quote a few lines from the State of the Union and I just have a question about this.

So one is, he quoted JFK about, “We're not rivals, but partners for progress.” Another one is, “My task is to report the State of the Union. The task of all of us is to improve it.” Another was, “We shouldn't make promises we cannot keep, but we must keep the promises we made.” And then the fourth one is, “Americans don't expect the government to solve everything. They don't expect everyone to agree, but we expect politicians to put the country first.”

Did you come up with those? The timing, the tri-colon, all that stuff? How did that magic happen?

Cody Keenan: Yeah, one of the tricks to drafting is to read it out loud to yourself to see how it sounds because it sounds different than it reads a lot of the time. For those ones you pulled out were usually--they're all kind of the same theme, which is we would try to build in.

I thought you were going ask me if we actually believed any of that, because a lot of it was saying…

Guy Kawasaki: You can answer that too!

Cody Keenan: Because a lot of it was saying, “People are counting on us to work together, to get things done,” but you also know in the back of your head, “Okay, we've been here five, six, seven, eight years. Republicans aren't going to do anything with us, so why include those lines at all?” Well, you always want to build in the possibility of compromise and action and give people a little bit of the benefit of the doubt.

Even if you don't think they're ever going to satisfy it, you build in the possibility that somebody might surprise you because it's better than just showing up and being like, “Look, you guys aren't going to do squat. I know that. So I'm just going to go do all this stuff on my own,” but that might be an exciting speech but I don't know how it would be consumed by kind of the political media environment.

It's interesting that you picked Kennedy stuff too, like, JFK is just catnip for any speech writer. Any democratic speech writers at least just come up devouring JFK and Bobby.

Guy Kawasaki: Martin Luther King…

Cody Keenan: Of course, MLK, all the big ones. We just consume that stuff, and you put them into speeches too because that will remind people of something as they hear it. Hopefully something good, and then tie it to you.

Guy Kawasaki: Specifically with a JFK or MLK quote, is it, “Oh, this is a great quote. Let's put it in the speech," or "This is what we want to say,” and then you find the quote. Which came first, the quote or the thought?

Cody Keenan: The thought, always. You don't ever want to build a speech around a good line because then it doesn't hold together well. The speech should be built around an idea, or several ideas, that tell a coherent story, and then if you can put a great line in that works with that story, that works with that speech, perfect.

But don't start from the other way around because often it just doesn't hold together. And we always marveled at Barack Obama's ability to--he disdained soundbites and good lines. Ben Rhodes and I would always try to sneak some great line into his speech. We were like, “This is it, man. This is the one that's going to be, like, carved onto a monument somewhere someday."

And I don't know if he just did it to screw with us but we'd sometimes get the draft back and just that line was crossed out like he knew what we were doing, and just be like, "Damn it. Well, we'll get them next time."

Guy Kawasaki: Okay. As you can tell, I'm really fascinated about the nuts and bolts of this process. When he gives the State of Union, where are you?

Cody Keenan: It depended on the year. The first time I was lead writer for it, I went to the Capitol and watched from the floor up against the back wall, and I always get kind of nervous watching it to see how it's consumed, but it was still pretty neat to be back in that house chamber, in a place where I started out my career, to watch the whole spectacle.

Guy Kawasaki: It's a long way from the mail room.

Cody Keenan: Yeah, that's true. I was actually allowed on the floor for once.

The next two years, I stayed at my desk just because, by the end of that process, you are so tired. The last two days of a State of Union Address in particular, when you've got now dozens and dozens of people, all trying to get their ideas in there and make edits, you're in charge of version control.

And there are now about sixty versions of the speech floating around with the fact-checkers sending you fact-checks. Policy people are sending you important edits that you have to make, then someone will just send through a random thought, and then you've got the president's edits. So those last couple of days are like driving a car with no doors, windows or brakes at 200 miles an hour and you're just hanging on for dear life.

So those two years, I sat at my desk and just ordered food from the White House mess and just cracked a beer because, at that point, there's nothing left to do but watch, and then my last year I went just because I knew I'd probably never do this again.

Guy Kawasaki: I watched the version that was the enhanced White House version, there were many times when they showed Paul Ryan clapping and nodding. I want to know, are there ten cameras on Congress, and then the editors at the end say, “Okay, so here's Paul Ryan. Let's just show him agreeing with Barack Obama, and here's Feinstein sitting next to Al Franken.”

And then how did they--how does that work? How do they make that enhanced version? It's a fascinating thing, right?

Cody Keenan: It really is. Not to disappoint you right off the bat, but I don't think our digital team of the White House had access to the cameras in the Capitol. So I don't think we got to pick and choose the shots. I think we just went with whatever the networks were doing, and the networks always wanted to get reaction shots from people like Paul Ryan and John Boehner, so we were at their mercy, but the enhanced State of the Union Address people don't know, it was kind of an interesting concept.

Our office of digital strategy came up with in the final, I think four or five years, where every year, like I said, the State of the Union Address has fewer and fewer viewers because people have more and more options of things to watch and do. I'm just speculating here, but I think probably like fifty years ago, but you fifty million people watch now it's in the high twenties. I think, it was maybe forty for our first one.

So we were trying to think of what are more interesting ways we can do this. People are increasingly consuming live media on their phones, on their computers, through various websites. So we partnered with Google to promote this enhanced State of the Union where we actually ran alongside in real time with the speech text, charts, graphs, photos, statistics, video, to make it interesting, and they worked on that so hard, and they were always hounding me for the latest draft so that they could make sure it was fascinating to walk into the digital office.

They had a whole wall devoted to this with hundreds of slides lined up, matched up to the text. And then when it goes live, they've got someone there putting the charts in and clicking post. And it was just a thing of beauty to watch. And I think a few million people watched it that way every year, but I thought it was really, really cool because we always struggle with how to reach people in a changing media environment, especially when people don't have the patience to sit and watch an hour-long speech.

Guy Kawasaki: Do presidents, or maybe specifically, Barack Obama and you, do you really care about the opposition party's response?

Cody Keenan: To the State of the Union Address in particular?

Guy Kawasaki: Yeah.

Cody Keenan: No, it's…no. If I could give one piece of advice to a politician, if I could give one piece of advice to a politician, it's never accept that task. There's always some politician who thinks, “This is going to be my big moment to shine on the national stage.”

They're all unmemorable and they're all really unfair to the speaker because you're following this enormous American tradition on the biggest of stages, and then they're coming to you, like, all alone in a room. You remember the bad ones, you don't remember the good ones. You remember when Marco Rubio had to lunge for a bottle of water?

You remember when Bobby Jindal, like, super awkwardly came around the corner in his house and walked towards the camera and it's just like, "Hi!" You remember the weird, awkward things. There's no great way to do it.

Joe Kennedy, who has become a friend, tried something interesting a few years ago where he did it live from a factory floor with a live audience, and there were cars parked behind him and it was cool. It was kind of a traditional, political setup but that for a traditional speech that nobody had really tried for live State of the Union response, but they never break through.

And part of that is because they're actually not responses, they're written beforehand because you have, what, twenty, thirty minutes to respond? That's not a lot of time to craft a really effective response. So they just come across as, “Did you even listen to the speech,” be a little tone deaf and it's just a losing proposition, and Senator Obama to his credit was clever enough to never do that.

Guy Kawasaki: Okay. I learned something in case I'm ever asked to do something like that. Did Barack Obama, or do you care about what the New York Times, the Post, or Fox News says about state of union or that's just…

Cody Keenan: Oh, I'd be lying to you if I said “no.” Of course we do. I took it personally all the time. I had super thin skin. I was looking--I was--I never would have admitted this at the time. I only admitted now that I'm gone, but I would look at all the write-ups and I'd be enraged if they were less than favorable. So I, yeah, I totally cared.

Guy Kawasaki: That would be like Tom Brady reading all the sports pages.

Cody Keenan: It drives me nuts. I would always do. I still do. If the president gives a big speech, I'll immediately go watch the coverage and I'll be like, “Oh yeah, you so-and-so, that's not true. It was a good speech.”

Guy Kawasaki: How does, if this story is true, how does someone like Meredith McIver happen to plagiarize Michelle Obama for Melania Trump? Like how does that happen? Fact-check…Well, I don't know about the Trump team, but you're talking about fact and all this stuff, how can plagiarism happen like that?

Cody Keenan: I try not to impugn motives to people when I don't know what I'm talking about, but worst case scenario, it happens because of sheer shamelessness and they just don't care, and I'm fairly positive they didn't have any fact checkers, otherwise it would never get through. We actually run our stuff nowadays through plagiarism software.

And I didn't know about that until I started teaching but there's this great anti-plagiarism software you can just run text through. So our fact-checkers do that at best case scenario, if you really want to give someone the benefit of the doubt, oftentimes when you're brainstorming speech and putting notes together and putting things together, you'll kind of clip things that you find inspiring or interesting ideas that you don't want to forget about.

Whenever I do that, I make sure to put them in, like, bold and red and italics so that I know this is somebody else's work. These are not my thoughts. My thoughts are in twelve point Times New Roman, these other person's sides are in like bold, red Arial. That's the most charitable interpretation, but knowing what we know about the Trump team, I just don't think they cared. And it was just so brazen.

How do you think you're going to get away with that?

Guy Kawasaki: Yeah, how do they think they're going to get away with that?

Cody Keenan: Well, it was an early test. I thought it was part of some strategy, but this was still, it was 2016, was still during the convention, and if there's one thing that the Trump team had throughout all four years, it was a general shamelessness where, "We're just going to do whatever we want, say whatever we want and we think we're going to get away with it. We don't care what the fact checkers say, we're not going to engage with them or push back. We're just going to tell the press and the media to stuff it, and we're going to do whatever we want,” and I think this was an early test of that proposition.

Guy Kawasaki: I hope we're not getting too tactical. You can tell I'm fascinated with this process. What word processor do you use? Is it Google Docs, or are you sharing Microsoft Word, or how does that?

Cody Keenan: So I'm old-school. I do Microsoft Word and I save a bunch of different versions every maybe every two hours I'll save a new version with a different timestamp, just so I can go back through all my versions. I despise Google Docs, and I think it's probably just an age thing. I just turned forty, but I just don't have a facility with it, and I really don't like other people watching me write and edit because I'm thinking out loud a lot of the time, and I don't want an audience while I'm doing that.

I'll share a Wordoc widely when it's ready, but I don't love the feature in Google Docs where everybody can watch everybody edit. It bugs me. I'm at a speech writing company now where everybody prefers to use Google Docs and so I go along with it. But the younger people on our team are just--they live in it, and it makes total sense to them in a way that it doesn't make sense to me.

Guy Kawasaki: I feel the same way, incidentally. Now tell me what you think about teleprompters. Is it a crutch, or a necessary evil, or just God's gift to speakers?

Cody Keenan: This isn't a cop-out here, I promise. It totally depends on the speaker and how much they're willing to put into a speech. So forgive me, there's a fire truck going by, like I said, Manhattan. It totally depends on the speaker. It's not a crutch, that's a common kind of insult, right?

When people want it to try to insult Barack Obama's intelligence is say, "Oh, he needs a teleprompter,” and those same people would use teleprompters. It's just, a) stylistically, it looks better. You can look up and down at your speech if you want to or you can use a teleprompter, and then if the camera's set up, people don't see the teleprompter, and you just look like you're a master of talking to an audience. Why wouldn't you want to do that?

It can be a crutch. If you are somebody like Donald Trump, who, you could tell, never looked at his speeches in advance. He had this tick where he would read something in the teleprompter for the first time and then he would adlib in, like, “Not many people knew that.” People would be watching.

We'd be like, “Yeah, we did. Everybody knows that.” That's, like, one of the most common things of all the time. So he would be surprised by what he was reading a lot of the time, when it's actually a strength. As I was saying before, once the speaker is familiar with the speech, hopefully they've even worked on it a little bit.

I think few speakers will work on a speech as much as Barack Obama will, then it's a total boon, it's like this extra super power. You get up there. You've got this speech that you've crafted, that you're thrilled with and it's right in front of your face with the crowd right behind. That just makes you a super hero…

Guy Kawasaki: And this person who's pacing the teleprompter, isn't that a skill and an art?

Cody Keenan: Oh man, I'm so glad you asked that! Nobody's ever asked me that before. I have a great story here. It's totally a skill, and it can be really high stress too.

Now in the State of the Union Address and other speeches like that, the president won't adlib much only because everything's exactly like he wants, but if he's in front of a more partisan crowd, especially a rowdier, more raucous kind of crowd that's just thrilled to come see him speak, he might add five or ten minutes to his speech and just go off the cuff and tell stories and make points.

And that's when it gets really complicated for somebody manning a teleprompter. You need somebody, I mean, it's so rare that you're going to have your own teleprompter operator who knows you and knows your habits. At the White House, it was called the White House communications agency, and it was career staff, and they're the ones who set up all the audio-visual stuff at the White House, wherever the president is giving a statement, whether it's in the East Room or Los Angeles, it doesn't matter. They travel, they set up all the camera equipment, they set up the teleprompter stuff, they run the teleprompter.

So there's a rotating crew of, I think, five or six people who would do it. And over time, they all knew, “You just stopped right there,” and the president could see on the screen that you've stopped, and that's when he starts out living and he knows he needs to come back and pick up on that thought that's coming up next.

And so the teleprompter operator would just wait. Only once, I was backstage at an event in Austin, Texas, and the teleprompter operator was brand new. And this was a rowdy crowd of University of Texas students who were having a great time and he was ad-libbing all over the place.

And she just kept turning around and throwing her arms up at me being like, "He's going off script!" And I'd be like, “He does that! Just be ready to jump back on." And she just keeps getting increasingly frustrated. And I was like, "I don't know what to tell you. He's going to say whatever he wants to say, just be ready to jump back in,” and she just got so pissed off about it. I was like, "Look, I don't know what to tell you. Just do it."

And somebody jumped in to help her who'd seen who had done it for him before, but that was the only time where we almost had somebody walk off the teleprompter job in the middle of a speech.

Guy Kawasaki: That would have been interesting! Enough about Barack Obama. Now let's talk about speaking in general. So this is a real softball, down-the-middle question, what makes a great speech?

Cody Keenan: What makes a great speech is…if it's memorable. And I don't just mean something that's quoted down the generations, but the point is, you've got this captive audience, what do you want them to know? What do you want them to go away from here and tell other people, or tweet out to other people? A captive audience is this precious gift. Somebody has come to watch you talk about your ideas.

So a great speech, simply put, is memorable. And to make it memorable, you make it colloquial. You don't get too lofty. You keep it simple and concise.

You build structural elements into it like, obviously, just tell a story with a beginning, a middle and an end, but you can build instructional elements knowing that your audience is listening, not reading. Let them know where you are on the speech.

Tell them that the next idea coming up is important. Remind them what you've covered already and what's coming up, but ultimately it's to make a speech memorable and have a stickiness to it. The worst kind of speech is if someone asks you afterwards, “What did she talk about?” And the person goes, "I don't know," then you've blown your whole thing. So now did we always follows those rules? Not necessarily, but there are differences there.

He might speak for a full hour, which I don't recommend to anybody else try to do, but he also had a press corps that would travel with him and that would take the speech and broadcast it out on their networks or write about it for the next day's newspaper or tweet it live.

These are just things that other speakers don't have, so I would recommend that you should just keep speeches under twenty minutes because that's really all anybody has an attention span for. There's no way this quote is true, I think it's apocryphal but you see it all over the internet that JFK once told the speech writers to keep speeches under 12 minutes because after that people only think about food or sex.

Guy Kawasaki: This twenty-minute number fits in perfectly with Ted, right? TED is eighteen minutes. Maybe it was two minutes of bullshit. So sounds right!

Cody Keenan: There is because the one thing about TED talks is you're supposed to just start talking. You get right into what you're going to say. And my least favorite part of any speech is the acknowledgements at the top. You just waste a couple of minutes thanking the people for having you, giving certain people shout outs. It just used to drive me nuts in the White House.

People would start emailing us, being like, "Hey, can the president give a shout out to this person?" “Why? What they do? They got driven from the Capitol to the White House just to be here today and now we have to say that they're here?” I don't understand that.

If we're signing a piece of legislation that somebody has spent their career trying to make happen, fine. One time I almost just totally lost it on someone. I don't even remember what the speech was at this point, but they just kept hounding us for all these acknowledgements to the point where the first minute of the speech was just nothing but pointing out that people were here and thanking people for being here.

And CNN had been taking the speech live and Wolf Blitzer cut it and they were like, "All right, maybe we'll come back to that later." And I was like, "See? We just had a captive, nationwide audience and we lost it because nobody wanted to hear Barack Obama thank the eighth member of Congress who made the brave trek from Capitol Hill to the White House."

Guy Kawasaki: Delaware.

Cody Keenan: Yeah. You can tell it really bothers me. So that's my favorite thing about TED talks is you just get into it.

Guy Kawasaki: I have to coach a lot of entrepreneurs, and I have this rule for pitches which is the “ten-twenty-thirty” rule. Ten slides, or ten main thoughts, twenty minutes, thirty-point minimum font on your presentation. That's the Guy Kawasaki “ten-twenty-thirty” rule.

Yeah. I also tell people that think of yourself as an airplane. You can either be a 787 and need two miles of runway or an F-18 taking off an aircraft carrier. You're an F-18. If you don't get off in 150 meters, you're in the ocean and you're dead.

Cody Keenan: Grab your audience right away. That's what they're there for. Wow them with something.

Guy Kawasaki: So now what makes a great speaker?

Cody Keenan: Oh, good question. No one's ever asked me that a good what makes a good speaker is somebody who...

Guy Kawasaki: Wait, wait, wait, wait, wait, wait. How can no one have ever asked you? That's the most obvious question to ask!

Cody Keenan: I don't know. You're smarter than everybody else.

Guy Kawasaki: Can I quote you?

Cody Keenan: Because I already asked what makes a great speech, right? But the answer is similar. Hopefully a speaker has taken the time to think through what they want to say, has developed some interesting ideas, has a unique worldview.

I can tell you the worst kind of speaker is someone who just says, “Write me a speech about ‘X,’” and never looks at it. Never interacts with it. Just gets up and reads it. Why would I want to do anything, buy anything from that person or vote for that person, if they--do they even have ideas? What do you believe in? Who are you?

So what makes a great speaker is it's very similar to what makes a great speech is like, have you taken the time to think through these things in your own head? I don't want to just know what you want to say, I really want to know why you want to say it. That'll help infuse the speech too.

And then you add on the things like charisma and knowing what to do with your hands, and interacting with the audience, and actually caring about your audience and having a sense of empathy, what they've gone through in their lives, what they want to hear, what they need to hear, and entertain them a little bit and give them a speech that is memorable.

That's easy for them to follow and easy for them to go disseminate. That's what makes a great speaker.

Guy Kawasaki: Do you think they're born or made?

Cody Keenan: Made. I think they're made. Yeah. I do. Was Barack Obama born charismatic speaker? I don't know because I never asked him, and I didn't ask him a lot about--we wouldn't just sit around and talk about his early life, but he'd talk at times about how he was a loner in college who was really just sort of monkish and into books and just living a barren existence. That's not somebody who strikes you as a born, charismatic speaker.

Barack Obama also paid for speech coaching when he was very early in his career. He hired, oh yeah, and people should! He hired David Axelrod to help him become an effective speaker I think at the early two thousands, like before anybody even knew who he was and that pays off.

If he'd gotten up there in Boston at the 2004 convention, without practicing, without coaching, and just wing that speech, you might not even know who he is anymore. Maybe he would have been a one-term Senator. I don't know.

I'm being I'm exaggerating, but what empowered him to knock that out of the park and go from somebody who walked into the fleet center, a relative unknown, and walk out of global megastar after just eighteen minutes is that he took the time to know what he wanted to say, put it down on paper and just practice the heck out of it.

Guy Kawasaki: That seems like a, “Why wouldn't anybody spend the time to do that?” Sheer stupidity…? Laziness?

Cody Keenan: I don't know…fear? It is an awkward thing to record yourself. I'll do it. To record yourself speaking and watch it back, it's always cringe-worthy. Nobody likes how we actually sound or what we look like, and, “Are people going think my ideas are dumb?” And it's just a nerve-wracking thing.

And then you pretend that you convince yourself, “Maybe if I don't really work at this, it'll just come and go away,” but don't squander that moment. Don't squander that moment. Practice until--I gave the commencement address at Northwestern University a few years ago in the football stadium, and there were 15,000 people there and I was just terrified.

The worst part is sitting there for half hour before I have to speak and still looking at everybody, and I'm just like, "Oh my God. Oh my God." But at that point, once you get up there, thirty seconds into it, I just felt this sense of flow because I had read the speech out loud to myself so many times and practice it so many times. I've listened to myself practicing so many times that you're basically now just going through the motions.

I already know what's there. And then because you're not panicking anymore, you can read the audience. If they're laughing or applauding, you can ride that; build in pauses. You can start to notice the inflection in your own voice and go higher to make a point that you want people to applaud for, or go lower to hammer home that, “This is something kind of emotional and powerful,” that you want them to feel.

And that's when it's really at its best. The President has this awesome paragraph in his book that, I remember reading when he first drafted a few years ago about the interaction between him and the audience. When just for this one moment, the two of you become one, just riding off each other's energy, and at its best, that's when speaking can be so addictive.

Guy Kawasaki: Pre-pandemic, I used to get fifty to seventy-five keynotes a year, so I understand it. Like time stops for me. And I can go up there--I have given speeches with a migraine headache that I thought someone was pounding a nail in my head. When you're on, you’re on. You just--the show must go on, and it's magical. It's for me anyway.

Cody Keenan: Do you practice?

Guy Kawasaki: I give basically about four speeches, the same four speeches all the time, literally hundreds of times. So in a sense, I've been practicing for twenty-five years. In another sense, in the sense that most people mean, no, honestly. I'm no Barack Obama, but I have given a lot of speeches. So it's second nature for me at this point.

So I read someplace or I saw you say…oh no, you had an essay, that in Silicon Valley, we will always talk about, "It's okay to fail," “fail fast,” “pivot," all that kind of bullshit. And like it's no big deal, and you have a completely contrary opinion. So why should people fear failure?

Cody Keenan: Yeah, I believe I gave the convocation at NYU's Wagner School several years ago, and there was actually my first public speech, and so I was afraid writing it, but that's what I came up with is that you should be afraid to fail. I do think there's a little privilege built in when you can think, “It's okay to fail because someone will be there to back me and pick me up and fund the next venture.”

There's the Michael Jordan kind where, “I've failed over and over and over again. And that is why I succeed.” Okay. Fine. But even while you were failing over and over, you're still also leading the league in scoring.

I think you should be terrified to fail because that's going to push you relentlessly to make sure you don't, to make sure you succeed. And for me, it was sitting at a computer at three in the morning, so terrified that I would screw up this draft and that Obama would hate it and that it would get panned, that I would stay up all night long and do what it took and talk to other people and read and make damn sure that this speech at the mark because it was so fricking afraid that it wouldn't, that I will push myself to any limit to make sure it succeeds.

And when I gave that speech, I was talking to a group of public student service and public policy graduates, and especially for young people going into those ventures, they're all dedicated to giving people a good education, to building water systems in Africa, to fixing our politics, to giving more people economic chances.

And these are things we can't fail at, and you should infuse all of this good work with that principal too. It's like, “I cannot fail these people. I'll do anything it takes to get this right.”

Guy Kawasaki: I worked in the Macintosh division for Steve Jobs and I tell people the contrary to all the sort of, “woo-woo,” positive psychology, HR theories that I was deathly afraid of failure, and deathly afraid of him because he would humiliate you in front of people.

I wouldn't say he was impolite. He was a-polite. And so he would just rip you. And I lived in such fear that it drove me to do some of the best work of my career.

And people in today's world, like, everything is about mutual goals and being open and transparent and focusing on the positive. When I tell them that fear motivated me, they don't know--their heads explode! They don't know what to do.

Cody Keenan: Yeah. It's interesting you say that because Barack Obama was not that way, but he had another way about him that would inspire your best work. Part of the thinking in that speech came from one of the worst things he ever said to me, which was, we'd been working on a speech together a couple of months before that, and he called me up to the table and I sat down next to him on the couch and he said, "You took a half swing on this. Take a full swing."

Oh man, that sucked because it just--he's not saying it's bad. He's not saying you failed. He's saying you can do better. “I know you can do better.” And I was just thinking about obviously it's a baseball metaphor, so just thinking about baseball, right?

You're watching Anthony Rizzo go up. Bottom of the ninth, two outs, bases loaded, two strikes. If he's going to strike out, at least you want to see him swing. What's even worse is if somebody strikes out not swinging at all. So that's why he said, “You took a half swing at this. Take a full swing.”

And that also gives you the permission to really let it rip. And by even saying, “Take a full swing,” implicit in that is, “You can do better. I know you can, I've seen it. So go do it,” and fear is involved in that too. I didn't want to hear that from him again.

Guy Kawasaki: Do you think the GOP is going to survive Donald Trump?

Cody Keenan: Man, that's…yeah, I do. It'll be interesting to see what it becomes. They don't really have any ideas anymore in general. No policy ideas at least besides slashing taxes on corporations and billionaires.

So what they're trying to do is rig the game. People can't vote for Democrats. They're stacking courts, they're passing onerous voting legislation, like, right in front of us on the state level. They're basically building in ways to not just say that the next election is illegitimate, but basically just to throw out the results, and that's a terrifying prospect. That means they don't have to run on ideas.

They don't have to win votes. They don't have to deliver for the majority of the population that have voted for Democrats in almost every election over the last twenty years. So that's frightening. And that would mean that they don't necessarily even have to survive Donald Trump to do all that. If I were a Republican, I'd probably be alarmed at this kind of cult personality in the party. It doesn't seem to be bothering any of them one bit.

Guy Kawasaki: In a stroke of great minds think alike, The Remarkable People podcast is sponsored by the reMarkable Tablet company. I wish I could tell you. I was so clever that I planned it this way. It's not true.

The reMarkable Tablet is a single-focus device. It's all about note taking. Not checking email. Not checking social media. Not checking websites. Focus, focus, focus.

And now, Cody is going to explain how he does his best and deepest thinking.

Cody Keenan: I love this kind of question because I ask it of people too. There's this thing among writers where you always want to ask a writer you admire, “How do you write? What's your method?” Because none of us like our own methods, mine is a mess. If you watched me, like, draft a speech, you'd be like, “Oh my God…”

So I'm always fascinated by how people do deep thought. And I've read a book on flow once and I don't think I've ever been able to recreate it, but right now…

Guy Kawasaki: I can't even pronounce that guy's last name!

Cody Keenan: Yeah! Right now, I have a six-month-old daughter at home and my wife and I both work from home, so there is almost no chance for true, deep thinking except for…I go on walks a lot. In the White House too, if I would get trapped on a page and you just--you wrap yourself around a sentence or a paragraph and work on it for like an hour and you realize you're not actually working on the speech anymore. You're just procrastinating working on the rest of it.

Once I can pull myself away from the screen and just go for a simple walk, I would find my neural pathways or whatever, just opening and reorganizing themselves to see something different. And I might just suddenly come up with a great idea that I never would have come up with if I sat at my desk for another hour.

Same is true here. Once we finally get Gracie, our daughter, down at eight, I might just go walk around the neighborhood at night because I've always liked the night better. It's just-- it's bigger. It lets you think. In the White House, you're just getting hundreds of emails a day too, which everyone is a constant distraction, and you can't really turn them off because we need to know what's going on.

And once those emails would slow to a trickle around 8:00 PM, that's when I get my best work done. And sometimes, if I went home to my apartment, I'd sit in the window and just look out into the city and work until two, three in the morning. I can't do that anymore because of the baby, but I do my best thinking and working in the middle of the night, when things just feel bigger and quieter.

We live a few blocks from the Hudson River. I'll just go sit there, and there's something about water that just--that's sort of primal, and then helps you think bigger thoughts, but I'll also take inspiration and thoughts from anywhere.

I try to read as widely as I can. I'm never going to admit to which ones they are, but there are lines in Obama speeches that were inspired by great lyrics in a song I heard or an advertisement on a bus shelter, or like a really good commercial. It's like, “That's a great thought. That's a great idea.” So I'll take inspiration from anywhere.

Again, you want to be careful not to plagiarize anything or even come close to it. But one of my rules about thinking is I don't have all the ideas or even the best ideas. Other people do. So if I make sure I'm listening, maybe I'll find something really interesting or a new way to think about something.

Guy Kawasaki: One of the things I learned from Steve Jobs is it's a skill in and of itself. You need to know what to steal. When you can steal a lot of things, you got to know what to steal. I’m going to ask you one more question but I cannot let you go without giving me this, which is a lot of this talk, it's almost like a pre-pandemic kind of talk.

So now what happens with speaking and speeches when it's all virtual? I haven't given an in-person keynote speech in a year and a half. So now what changes? What do we do? How do you compensate for this?

Let's say that you're invited to give--I had to give a commencement address virtually. So you get invited to do something virtually like a commencement. How do you translate your skills into a virtual keynote? What do you do?

Cody Keenan: God, I had to do this last year too. I gave one last June, and you have to do a lot different because the sad thing is you're not looking at anybody. There's no audience looking back. This was broadcast live out to the graduating class, and so I'm looking at myself which is a total drag.

So there's a lot of imagination going on. I'm telling myself, “Just keep staring into the camera lens. They're out there watching. You don't know how many or what they're doing, but they're out there,” and it--but it's a real drag for the speaking aspect of it because when you're writing a speech, you build in applause lines, you build in jokes.

So I actually took a couple of the jokes out of my speech because if no one's laughing, you don't know how they land, and they--it just sounds like they're not landing at all. There's a little more performance aspect to it. Like I might hold things up or pull something out of nowhere.

Like the baby comes around the corner. You can have a little fun with your background. It doesn't have to be perfect or like have a pineapple in it, whatever that's all about. I played with the ideas of doing one live as I was walking through the city. I just said, “There's no way. Too many unknowns there,” like sirens going by. It's not worth the effort.

By and large, I think you keep it short. I had to work on a couple for president Obama last year and you're like, “Let's just…Normally for a commencement, we do maybe thirty minutes. Let's just keep this to ten or fifteen.” Even though you're Barack Obama, it's just, it's still a lot to ask somebody to just watch a video of you talking for a half hour.

Guy Kawasaki: The commencement I made was for UC Santa Cruz School of Engineering.

Sign up to receive email updates

Leave a Reply