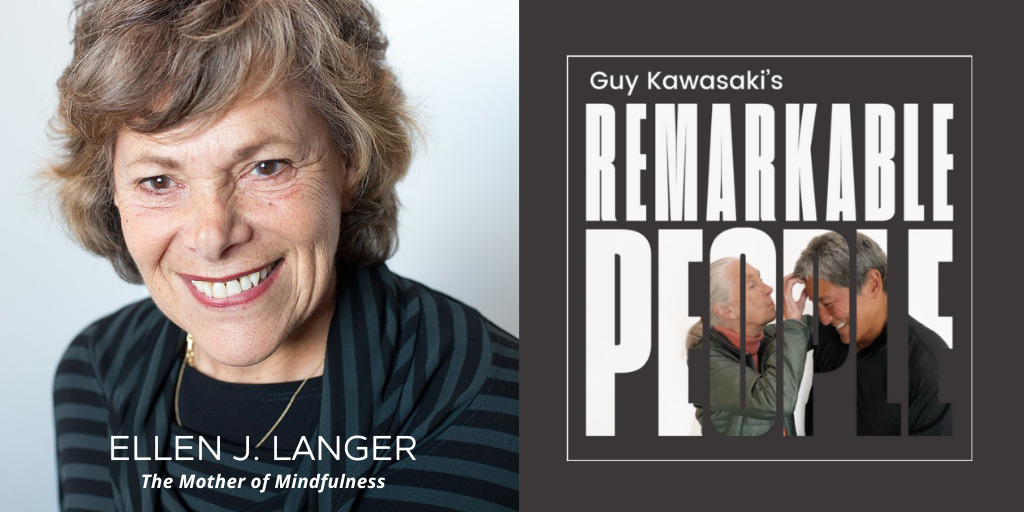

Welcome to Remarkable People, where we’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Ellen Langer.

Ellen Langer is no ordinary psychologist; she’s often referred to as the ‘mother of mindfulness’ and has spent over 35 years as a professor at Harvard University.

Her groundbreaking research has transformed our understanding of the human mind and its incredible potential.

Ellen is the author of 11 books, including bestsellers like ‘Mindfulness’ and ‘Counterclockwise,’ which reveal the transformative power of noticing, flexibility, and embracing uncertainty. Her work has earned her Guggenheim and scientific awards, and she’s garnered praise from thought leaders across various disciplines.

Join us on this remarkable journey as we uncover the secrets to living a more fulfilling life, one shaped by mindfulness and the endless possibilities that lie before us. Ellen Langer’s insights are sure to leave you inspired and motivated to explore your own potential. Stay tuned!

Please enjoy this remarkable episode Ellen Langer: The Mother of Mindfulness

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Ellen Langer: The Mother of Mindfulness

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People. We're on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is the remarkable Ellen Langer. Ellen is the mother of mindfulness. She is one of America's most influential psychologists. She's been a professor at Harvard for over thirty-five years and has pioneered groundbreaking research on the psychology of possibility, mindful learning, and the mind-body connection.

Her trailblazing studies demonstrate how our thoughts and perspectives can profoundly shape our health, happiness, and wellbeing. Her latest book, The Mindful Body, is a deep dive into this topic. If you've heard about the famous study where the word "because" seems to have special powers, this was Ellen's experiment. Ellen has proven we have more control over aging and illness than commonly assumed. Changing our mindset can improve vision, hearing, chronic symptoms, and with effort, people of any age can surpass presume limits.

This episode of Remarkable People is brought to you by MERGE4, M-E-R-G-E and the number four. I'm an investor in the company because they make the world's coolest socks. In fact, if you ever see me ask me if I have MERGE4 socks on and if I'm wearing any socks that are not MERGE4, I will give you a pair of Merge4 socks. For those of you who don't encounter me and don't win this challenge, you can get a 30% discount by using the promo code, “friendofGuy”. No capitalization, “friendofGuy”.

Anyway, I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People. And now, here is the remarkable Ellen Langer.

We interviewed Carol Dweck a few weeks ago, so we had the mother of the growth mindset and now, we have the mother of the mindful mindset. So, now, we've got all the mindsets covered. So, this is a big day for us. So, we recently had a guest named, Jerry Silver and he is an expert in spinal cord injury recovery. He has license plates that say, "Glia Man," G-L-I-A M-A-N, because he deals with neurons and glia and stuff. So, I want to know if your license plates say "because."

Ellen Langer:

No, but actually, my license plate without me having ordered it says MDF and then I don't know what the number is. So, I took that as mindful, but I didn't create it myself. This Jerry Silver should be a good driver because you don't want a license plate that's so easy to be remembered leading by the policeman.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, people are warning, "Why is Guy asking her about 'because'"? And people have asked me about what's it like to work for Steve Jobs or "Are you related to the motorcycle company" thousands of times. So, you may be sick of this question, but you got to explain your photocopy and "because" study.

Ellen Langer:

Yeah. This was one of the first mindlessness studies that I did and we had somebody go over to somebody at a Xerox machine when they still recall that and people use them and ask them if they could use the machine because they wanted to make copies. Now, that's an empty request because what else are you going to do with the Xerox machine except make copies.

What we found was when the person who is asking for the favor said "because" and then followed it by anything. People were likely to give into the favor and say yes. And the "because" followed by "because I want to make copies" is totally meaningless. And essentially, it was the first study that showed me that, "Gee, people may not be there much of the time."

Forty-five years later, I can say with great confidence, almost all of us are not there virtually all of the time. What's the next question you're going to ask me or I'll just assume there's a question and answer it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Has there been any more recent thinking about the power of "because" and why it works?

Ellen Langer:

If so, I'm not aware of it. My purpose in doing the study was essentially to show that most of us are not there and we're not aware that we're not there because when you're not there, you're not there to know you're not there. And that this is ubiquitous. The "because" is a way of saying that there's some meaningful explanation that's going to follow. And so, the person tunes out. They don't need to listen to it.

Now if I said to you, "Can I get ahead of you because I want to cut off your arm, I need an extra hand," chances are you're not going to let me do it. There were better and more convincing tests of this mindlessness. But after forty-five years, I tell you that what we find with just very little instruction for people as to how to be mindful, what we end up with is an increase in health, happiness.

People who are mindful are seen as more charismatic. Relationships are better. It improves virtually everything. And when you perform mindfully, you actually leave your imprint on the product that you're making. So, it's easy, it's fun, and it couldn't be better for you. So, my assumption is once somebody hears about it and how easy it is, they will do it.

Now what happens, Guy, you're going to ask me, "Why is it so easy?" Because a lot of people confuse mindfulness as we study it with meditation. Meditation is an entirely different thing. Meditation isn't mindfulness. Meditation sets you up for post-meditative mindfulness. For mindfulness, as we study it, it's just noticing, noticing new things about the things you think you knew. Then what happens is you see, gee, you didn't know it as well as you thought you did. So then, your attention naturally goes to it.

So, let me give an example. I start lots of my lectures this way. Guy, how much is one plus one?

Guy Kawasaki:

Two.

Ellen Langer:

Yeah. And you think, "Why is she asking me this? Is there's some problems she has?" Because we know our facts. It turns out that one plus one, the thing we think we know better than anything else is not always two. If you add one wad of chewing gum plus one wad of chewing gum, one plus one is one. If you add one cloud plus one cloud, one plus one is one. If you add one pile of laundry plus one pile of laundry. In fact, in the real world, one plus one doesn't equal two, probably as or more often as it does, but we think we know.

Now, interestingly, if you just think about it now, and let's say later today somebody should ask you, it's unlikely, but somebody asks you, "Guy, how much is one plus one?" You're not going to quickly say, "Two." You're going to pay some attention to the context. All right. And so, you see that when you don't know, you tune in and you can tune in or learn that you don't know in two different ways.

So, the first way, as I told you is just notice new things. Notice three new things about your spouse, your boyfriend, your girlfriend, three new things when you open the door and look outside. And gee, you just didn't know it as well as you thought. The other is to adopt an understanding of uncertainty, a mindset for uncertainty.

This is the only mindset I believe anybody should have. Everything is constantly changing. Everything looks different from different perspectives. So, we can't know. And we tend to confuse the stability of what's on our mind with the underlying phenomena so we think we know. And we do that in order to feel some control. But by doing that, we're actually giving up control.

All right. So, people are afraid not to know, and you're talking to your boss and you pretend you know. He's pretending he knows, or she, that if we recognize that it's not that we alone don't know, because we don't make a personal attribution for not knowing. Instead, we make a universal attribution. I don't know. You don't know. Nobody knows. And then everything becomes potentially interesting. And the situations we've avoided now we might eagerly approach.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. So, I just want to point out to the listeners, because this is a world-class example of how I asked her about the word "because," and she transitioned it to what she wanted to talk about, which is mindfulness and her book. And that was one of the smoothest transitions I have ever witnessed in my career. And I'm saying this because I want Ellen to know, I noticed, okay. Steve Jobs would've been proud of that transition. All right, so now hypothetical. Okay, Ellen?

Ellen Langer:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let's say that you and Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi go into a bar, and you talk about mindfulness, and he talks about flow. What comes out of that conversation? What's the difference between flow and mindfulness?

Ellen Langer:

That's an interesting question. First of all, there's great overlap. Now, I'm a social psychologist talking to one audience and Mike, as we call him because it's easier than pronouncing his last name, was when he was alive, a personality theorist. So, it's not unreasonable that there'd be similarities that we both came to at basically the same time.

The major difference is he believes that flow is a very unusual event. I believe that becoming mindful is very easy. And when you're there, fully there, you're going to be experiencing more or less this flow state. Now, everything he says about flow is also true when you're completely mindful and you're wonderfully creative. There's nothing standing in your way.

Guy Kawasaki:

But my at least superficial understanding of mindful is that I'm truly in touch with my feelings, my body, what's happening. But when I believe I'm in a state of flow, particularly writing, I think I'm completely absent of perception of my body, my state, my environment. I only think about writing.

Ellen Langer:

Yeah. You're misunderstanding mindfulness. When you're mindful, you're totally engaged in whatever you're doing. It doesn't matter. It's the same writing. However, when you're writing and you start off as mindful, you have a soft open awareness to your entire body. And so, if you were having difficulty breathing, you would notice it sooner than before you just passed out.

So, the more mindful we are, the more aware we are of wherever we put our attention. But when I put my attention, let's say, to our discussion now, Guy, there's still part of me that is not totally oblivious to everything around me. I'm not attending to it, but it wouldn't take me very long for instance, if somebody in the other room screamed. Where for somebody else who's learned about the world mindlessly and assumes they know when they're doing one thing, they're blind to everything else. You can never attend to everything.

But what you want when you're mindful is to be aware that you should not be certain of anything. You should never be mindless. Okay? So, you're either mindful, potentially mindful or mindless. When you're mindless, you're not there. Now, you're going to ask me, "Isn't there sometimes an advantage to being mindless?" Another fast transition for you, and I'm going to say, "No. It's never to your advantage unless two conditions are met."

The first is you found the very best way of doing something, and second, the situation doesn't change, which those two circumstances are never going to be met. So, you say, "Okay, you're in a park and you're with a little kid. And the little kid wanders into the road. Isn't it better to just mindlessly grab the child to get him out of harm's way?" And I say, "First of all, if you were mindful, the child wouldn't have been in the road." Second, that if you grab that child mindfully or mindlessly, the difference is only going to be milliseconds at most.

And if you're there, you might notice that the way the driver of the oncoming car is turning the wheel, so you take the child in the other direction. You don't just randomly move the child and hope that you've guessed correctly which way the car is coming. And when I tell people they should be mindful all the time, another group of people shut it. "Oh, my gosh, it sounds so hard," because they don't understand. They confuse mindfulness with thinking and thinking has gotten a bad rap. Thinking is fun. What's not fun is worrying about making a mistake, worrying about not being able to solve the problem.

If you came and visited me, so I know you're in California now. I'm on the East Coast. You've never been to my house here. It's lovely. If you came to visit me, you'd look around. Everything would be new. You might notice different objects in the house. You wouldn't have to practice it. You would just naturally because you don't think you know.

If you're going to take a vacation, you're expecting to see new things, and people find vacations energy-begetting, not consuming. When you're at play, you're being mindful. If you're not noticing new things, it's not fun. If you did a crossword puzzle and then did it again where you now know all the answers.

All right, so mindfulness is the essence of engagement. When you actively notice, that puts you in the present, makes you sensitive to context and perspective. You could have rules and routines, but they shouldn't tell you what to do. They should gently guide what you're doing. When you're mindful, you can take advantage of opportunities to which other people are blind and avoid the dangers not yet a rhythm.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm in Santa Cruz, so I got to ask you this question. Do you think mushrooms can enhance mindfulness?

Ellen Langer:

It's interesting. I think that if you ate an ordinary mushroom, but you ate it with the understanding, you ate it with the desire to actually taste it and taste how each part of it, each bite is different from the last bite, yes. The way I eat too often is I taste the first bite and then I just eat mindlessly, which is not good. Sure. In fact, that would be a fun study where we give people like you mushrooms to eat and we lead you to believe it's a special mushroom. And my guess is it would have an awakening effect on you.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, do you have any more tips for getting into the mindful state other than mushrooms?

Ellen Langer:

No. It's very easy. Recognize that you don't know. If you don't know, you're going to pay attention. If you think then when you're looking at the things you think, notice the ways they're different and then you'll see, gee, you didn't know it as well as you thought. And then you're on your way. And you see it feels good. It's the way you are when you're engaged and who doesn't want to be engaged?

It is so easy that it almost defies belief. But after forty-five years of research, I can say with as much confidence as one can say with anything, that it extends one's life. Our injuries heal more quickly. People find us charismatic. Our relationships improve, our memory, our strength. It's phenomenal. So, ask me about mind-body connection and unity and all of that.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, one of the consistent themes through your book is this question about when and if rules matter and how the mind can defy many rules and myths. What are the limits of that? If you've got a gunshot wound, you're not going to just think, "Oh, I'm going to be fine. I don't need to take the bullet out and get sutured." So, what's the limit of mind-body?

Ellen Langer:

You asked two separate questions. First about rules and the second about health healing and what have you. And they're the same and they're also separable. So, first, with respect to rules in general, don't cross the street, that kind of rule, which has nothing to do with taking a bullet out of your own.

Once we recognize that rules were written by people. My favorite example, I'm a tennis player, intermediate. And so, I serve the ball, throw it up, hit it, I kill it, it doesn't go in. And then I have a wuss follow-up second serve. If I wrote the rules, you'd have three serves. The first one, you kill it. The second one, you also try to kill it because now you've learned something and then you still have your baby follow-up serve. All right. So, it's only because somebody different from me wrote the rule that I'm not as good a tennis player as I otherwise would be.

All right. So, the point is to recognize that most of the rules that we mindlessly follow weren't handed down from the heavens. It was somebody's view of how to do things and this somebody existed at a different time and it may or may not be to your advantage to continue.

When I give talks, sometimes I look in the audience to see if there's some real big guy and I invite him up to the stage. So, I'm five foot three inches. I try to find somebody over six foot three inches. We look silly next to each other. I ask him to put his hand up. I put my hand next to his hand and you can see his hand is about three inches larger than mine. And then I raise the question, "Should we do anything the same way physical?"

So, the point is the more you're different from the one who created the rule, the more important it is for you to question the rule and to instead of doing it their way to do it your own way.

Now, as far as the healing goes, can we back up a little bit so I can put this in context for people? All right? I dare you to say no. Okay, so what a lot of this book and a lot of my research is about is about mind-body unity. And with mind-body unity, what I'm suggesting is it's not that we have a mind and we have a body, then we have to figure out how do you get from one to the other? See it as one thing. And when it's one thing, then wherever we put the mind, we're necessarily putting the body. And so, we put the mind in unusual places, take our measurements from the body.

Let me give you a little history first because this book, The Mindful Body, started as a memoir and then became the book that it is. So, I have lots of personal stories. So, I was married when I was very young. And we go to Paris on our honeymoon. And I order a mixed grill and one of the items on that mixed grill is pancreas. I shudder at the thought of eating it.

Guy Kawasaki:

I love this story.

Ellen Langer:

I asked my new husband, "Which is the pancreas?" He points to it. Okay, so I'm a big eater, I eat everything with gusto. Now comes the moment of truth. Can I, now a woman of the world, a married woman, eat this pancreas and I'm getting sick while I'm eating it. And he starts to laugh. And I say, "Why are you laughing?" And he said, "Because that's chicken. You ate the pancreas ages ago." All right. That was my first experience, personal experience with mind-body unity.

Let me just tell you one other quickly before I tell you about some of the research. This was a more important experience. My mother had breast cancer. It had metastasized to her pancreas. Oddly, both stories about the pancreas. When the cancer reaches your pancreas, that's the end game. So, she was told she had very short time to still be alive. Then magically, it was totally gone and the medical world couldn't explain it, but I could explain it with this idea of mind-body unity. Okay, so now, we do lots of tests. Do you want me to tell you about some of them?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes, absolutely.

Ellen Langer:

The first one people might know about, because I've written about it before, is the counterclockwise study. I can call this a famous study guide because if you turn on The Simpsons, go to “Havana”, they actually describe the study. What we did was we retrofitted a retreat to twenty years earlier and we had old men live there as if they were their younger selves. So, they spoke about past events in the present tense for example. All right. And they spent just a week there.

And a period of time of one week, what we found was their vision improved, their hearing improved, their strength, their memory, and they look noticeably younger without any medical intervention, without any face work, all right, without any hearing aids. By putting themselves in their younger bodies, in their younger cells, their body is cooperated. And most people know about placebos, which I think are basically our strongest medicine. In some sense, we gave these people a social placebo. Okay. So, now we have many studies. I'll just tell you about two to make sure people understand the power of this.

The next one we did in that series was several years later. We did this with chambermaids. So, you ask chambermaids how much exercise they get and oddly, they say they don't get any exercise because they see exercise is what you do after work and after work, they're just too tired. All right. We teach them, one group of them, that their work is exercise. Making a bed is like working on this machine at the gym and so on. So, now we have one group sees they work as exercise. The other, it doesn't occur to them.

We make sure we take lots of measures. We make sure by the end that they're not eating any differently, they're not working any harder. Still, the differences we found were phenomenal. The group that now changed their minds saw their work as exercise, lost weight. There was a decrease in waist to hip ratio and a decrease in body mass index. And their blood pressure came down. We believe just from the change of mind.

Now, let me just give you the very last one, the newest one. We have people, we inflict a wound. Okay. It'd be nice and dramatic if it were a big wound, but obviously, I don't want to hurt people and I doubt that the review board would let me. Okay. So, it's a minor wound, but a wound nonetheless. People are sitting in front of a clock. For a third of the people, the clock is going twice as fast as real time. For a third of the people, the clock is going half as fast as real time. For a third of the people, it's real time. The question we're asking is would that wound heal based on real time or perceived time, which is what the clock is telling them.

And obviously, I wouldn't be telling you this if their wounds didn't heal based on their beliefs about how much time had passed. We have people in the sleep lab. You wake up, you think you got more sleep, less sleep or the amount of sleep and what happens, your biological and physical functions follow your perceived amount of sleep.

All of this just says we have so much more control over our health than most of us realize that it's phenomenal. So, now we go back to your question, the person who was wounded, should we take the bullet out or just tell him to change his mind about it. I'm still of this earth, although some people question it, so I say, "Sure, take the bullet out."

But I think his healing will depend on his state of mind and how mindful he is, number one. Number two, we really don't know that if the bullet stayed there, people don't realize this is scary. But the number of sponges that are left in people after surgery, it's frightening. And yet, these people, they don't know the sponge is there and they live their regular long life.

So, maybe with the bullet. But if you ask me, should you take it out? Sure, take it out. But then, your psychology counts. And now, we have a study going on where we rather than do what the medical world does, which will tell you how long it's going to take for you to heal. So, you break your arm or where that bullet has hit you, it's going to take six months to heal. We have a setting now where we find the very quickest healing time that anyone has done and we're giving that to people as possibly how long it'll take. And I think that people will heal faster.

Guy Kawasaki:

But people listening to this and they just got a diagnosis for breast cancer and they listen to this and they say, "Oh, I just heard about mindfulness. I'm not going to get chemo. I'm just going to focus my mind on this." So, where do you draw the line? When do you listen to your oncologist versus your psychologist?

Ellen Langer:

I don't think it's mutually exclusive. I think that if you are part of the medical world and your doctor and your family are all suggesting that you get chemo, I'm not telling you not to get chemo. I'm telling you that whether or not you get it, you can enhance your health. Cancer is an interesting thing. Remember I started all of this with my mother who had a spontaneous remission, which the medical world thinks is very rare. I don't. We don't know how many of us have had tumors that we don't know we have and then we don't know, but they're gone. They may not be that infrequent.

And it's also the case that when we're diagnosed with something where we're told we have no cure for it, I find that offensive because people often hear that as they should just be helpless. And there's always stuff you can do.

I showed this slide in some lecture. I think it was in my class or whatever, during COVID when they didn't have a cure for COVID. We have one now. And I had an Olympic athlete, so she is running. You can see her jumping over the hurdles and very strong. And you have somebody else who is in a bathrobe and sort of lazy watching television, which I enjoy watching television. She's eating chocolate, which I also enjoy, but it's clear, this is the way she's spending her afternoon, which I don't think is the best way.

And I simply asked them if they both were exposed to COVID, who do you think would suffer more from it? And I didn't do any research on it, but it just seems to me intuitively that world-class athlete who's stronger. So, if you have some disease where there's no cure, you certainly can do things to make the rest of your body stronger. And in doing that, I think we do ourselves a great service.

And also, Guy, we have a lot of research that you know about, but your listeners don't on this psychological treatment that I call attention to symptom variability, just a fancy way of talking about mindfulness, noticing change. That's what being mindful is, is noticing. And so, we take people who have big diagnoses. We haven't done with cancer, but we have multiple sclerosis, chronic pain, stroke, big things.

And what we do is we call them periodically and simply ask them, "How does it feel now? Is it better or worse than the last time we called and why?" And we do this a few times a week in the course, a few times a day in the course of a week and maybe two weeks depending on the disorder.

Now, three things happened with this. The first is let's say pain. People who are in pain think they're in pain all the time. No one is anything all the time. So, when we call them and they say, "Oh yeah, right now I'm not in as much pain," they instantly feel a little better. Second, by asking people why now and not before. "Why are you a little better or a little worse?" They're doing a mindful search. And as I've already told you, when we make people more mindful in this active noticing way, health improves and they actually live longer.

The third is that I believe you're much more likely to find a solution if you're looking for one. So, let's say, Guy, that you're one of these people who thinks you're stressed all the time. No one is stressed all the time. So, now I call you and somebody else is calling you periodically to find out when are you more or less stressed and you discover you're maximally stressed when you're talking to Ellen Langer. Okay. The cure is simple. Don't talk to me.

Guy Kawasaki:

Not true.

Ellen Langer:

All right. It's good for you to go on this search. You don't feel helpless. You're actually noticing things. The neurons are firing, which I said is literally and figuratively enlivening. And across all these different diseases that we've looked at, we find a significant improvement.

There's something else that I talk about in the book that supports the mind-body as one, mind-body unity idea. Remember the borderline effect? In the borderline effect, let's say for argument's sake, Guy, you and I both took an IQ test and let's say you get a seventy and I get a sixty-nine. The way psychologists look at that is now I'm cognitively deficient. I have problems. Nobody in their right mind would think there's a meaningful difference between our scores, sixty-nine, seventy. I could have sneezed and gotten the question wrong.

But from that point forward, we go six months out, our lives will be enormously different. People will treat you. You'll treat yourself as if you're normal. I will treat myself and be treated by others as if I'm not. And it snowballs. So, we did this with cancer and we did it with diabetes, where we looked at people who were just a little bit above, just a little bit below the diagnosis, whatever the measurement was. So, it was no difference.

But yet over time, there is a difference. And the only way to explain that is by psychology. That there are ways we can spire against ourselves. And just by knowing, that doesn't have to be so may go a long way in helping us stay healthy.

Guy Kawasaki:

One of the topics you brought up and as a marketer and as an entrepreneur I found so interesting is you talk about empathy. And to use business examples, Toyota has this concept of go and see, which is if your factory's not operating well, instead of just looking at reports, you actually go onto the factory floor and look. And then our friend, Martin Lindstrom, he has a theory of go and be. So, not just watch the factory but be one of the workers, which is even better. So, I think that's where we're crossing into radical empathy.

Ellen Langer:

I take it a step further. Go on.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, take it. Go from here.

Ellen Langer:

I think that anything that leads us to understand each other better is obviously good and something I'd be in favor of. But this was something I learned a while ago that is probably the one thing that's been more important to me than anything else over these forty-five years of research on mindfulness. And that is that behavior makes sense from the actor's perspective or else the actor wouldn't do it.

What that means is that every time we're casting aspersions, putting somebody else down, belittling them, we're being mindless. Let's say for example, Guy, you might not like me because I'm so gullible, which I am, but that's because from my perspective, I'm trusting. I can't bear you because you're so inconsistent. From your perspective, you're flexible. So, it turns out for every single negative ascription we have for people, there's an oppositely balanced, so you say negative, a positive, that's equally strong.

And then what happens is we don't want to change each other quite as much. And then, this experience happened to me. Okay. So, I'm at the house here. And we have a big basement. And we're expecting a large load of furniture to be stored. And there's a guy here, remember now, I'm a genius, all these wonderful things. And he by all accounts, he's uneducated. He's depressed. He doesn't think he's worth very much at all.

All right. I am sure there's no way they're going to get all that furniture in the basement. He not only gets it all in but gets it in so that every single piece there is available to be used. It's incredible. And then I thought it's just not fair. And so then, I wrote a little song that I'm not going to sing to you. Actually, I wrote it for my grandkids, but I have my Harvard students sing it, which is that everybody doesn't know something but everybody knows something else. Everybody can't do something, but everyone can do something else.

And that once we recognize that all these people that we see as less than or in a company, they don't have anything to offer, we can start to view them differently, value them, and then we all prosper. I was giving a talk to some group in South Africa. And I was staying in this very fancy hotel.

So, one afternoon, I went down to the pool and I wanted to be separate from everybody. I don't know why. And I noticed that there was a tremendous amount of real estate, so to speak, that the hotel owned that was totally unused. It was only the cabana boy, the "lowly" cabana boy who had this information. And had he been respected enough, he would've had a way to give this information and increase the bottom line, which is what most businesses are really easiest to doing.

But when we take ourselves apart, it's the same thing. That we did what we did because it made sense when we did it or else we wouldn't have done it. And rather than looking back at it and looking at myself as gullible, for instance, are you looking at yourself as inconsistent to recognize that you did it because of your being flexible or my being trusting. You end up with even more empathy than you would have just saying to yourself, "Gee, let me try to think kindly about this person."

And sympathy is the worst because that says, "Boy, they really have this terrible thing." And what you're going to do is acknowledge that they have it and try to get past it rather than recognize the virtue that it actually brings with it. You want me to give you a chance to talk?

Guy Kawasaki:

I will have to mention that you are the first guest in 200 that got to the recording half an hour early. You've established a new record. No one ever has done that.

Ellen Langer:

And Guy, that's because I'm an anti-procrastinator.

Guy Kawasaki:

Getting back a little bit to radical empathy.

Ellen Langer:

I'm an anti-procrastinator. I do everything early. And that if I'm going to sit someplace waiting, I might as well sit in front of the computer. So, if you are there early, we can start early and have more time to tease each other.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. This is what I want to ask. My question is, I love the discussion of empathy and radical empathy, but you threw a wrench into the works when you discuss The Prince and The Pauper, which is to say the prince acts like a pauper, radical empathy and all that. But at the end of the day, the prince goes back to the palace.

Ellen Langer:

Right, exactly.

Guy Kawasaki:

And the pauper is still a pauper. So, now what do I do? Are you saying radical empathy is overrated?

Ellen Langer:

No, I think what's called radical empathy is better than a little empathy. But I think that a mindful empathy is even better. That when the prince is putting on the clothes of a pauper and walking the streets, yes, the main difference is that he knows he can stop being a pauper at any time. And this is the one thing the pauper can change. And so, when Martin Lindstrom, it's wonderful, let him go be a worker. But he also knows that at any point as the prince, he can say, "Okay." And so there's a limit to just how much information we can get by that, but certainly it's worth seeking.

Guy Kawasaki:

If you want another Martin Lindstrom story, he's been on this podcast and he told the story of being retained by a pharmaceutical company who wanted to "get closer to the customer." And so, what he did, instead of hiring McKinsey or Arthur D. Little, what he did is he took those executives and he made them breathe through straws. And after they struggled, he said, "This is what it's like to have asthma." But as you just pointed out, after that exercise, they threw away the straws and they went back to normal living.

Ellen Langer:

Martin is terrific and I think that's a wonderful exercise. But as we've just said that to notice its limits, he then, I assume, would discuss that with the drug makers that, "Well, you suffered and couldn't breathe. At least you knew that you take out the straw and you're fine. People don't have that possibility."

So, it's saying you're getting some information, but don't for a minute think that now you know what it's like being in somebody else's shoes. And the whole idea of walking in somebody else's shoes, if I've been walking in my shoes, so to speak, for seventy years, seventy, how old am I now? Seventy-six years, and you're going to put my shoes on for five minutes, how dare you think you know what it's like. So, there.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, jumping back a little bit because I feel like you're Hercules and you're diverting a river, and I'm just trying to swim upstream and trying to not drown in this interview. So, you talk about examining people's intentions and from their side, what they're doing is making sense. So, how far can you push that? Can you look at January 6th and say, "Oh, I understand why those thousand people attacked the Capitol."

Ellen Langer:

Sure. If you were taught, let's take one step even worse, if there is, which is Nazi Germany. If you grew up and you were taught that Jews are vermin and they carry disease and the only way to get rid of vermin is to kill it, and you're brought up this way for a short lifetime, then I think it makes sense that you would then when face-to-face with a Jew, try to kill the person.

Now, clearly as a Jew I can say that I'm not suggesting that this is proper. I'm not suggesting with what people did in DC that the law should look the other way. But I am suggesting that if you want to change a situation, the best way to change it is to find out why the person is engaged in it in the first place, which we often don't.

If you want me to stop being gullible, no matter how many times you persuade me that people are gullible, seem weak and so on, "Oh yeah, I don't want to be gullible," but then I'm going to fall back into it. Why? Because I'm not being gullible. I'm being trusting. So, you want me to stop being gullible? Get me to not value being trusting. If I want you to stop being inconsistent, I have to get you to not value being flexible or else, what would more likely happen is we'd accept it. But we're not going to accept murder and murderous acts and transgressions that are costly to people.

Guy Kawasaki:

How do you make mindful decisions?

Ellen Langer:

Most people are making decisions pretty much the way they should, but they suffer terribly worrying about are they making the right decision. And so, look more closely at decision-making and realize several things. First, you can't possibly sensibly do a cost-benefit analysis because there's an infinite regress. So, how do you decide what's a cost and how do you decide that's a cost and how do you decide that and so on. That's the first thing.

The second, and it's so important, especially when we were talking about stress, that events are neither positive or negative. We make them positive or negative by the way we understand them. So, let's say, Guy, to celebrate your birthday, you decide the two of us are going to go out to eat. And the food is wonderful, "Yay, it's a hit." Now, if the food is awful, "Yay, that's a hit," for me because I'll eat less and that'll be better for my waistline. All right.

If it's the case that in equal measure, again, every positive is a negative, every negative is a positive. You can't add them up to see what to do because it's going to add up to zero, if it's equally positive and negative. So, you can't be doing that.

Second, then even if you thought you could do that, nobody tells us and there's no natural endpoint to the information you could bring in to make the decision. I can't decide whatever you've asked me because I have to take the next three years to think about it. When is enough? There's no rule for that. When you add all of us together, which is hard to do. But before I give you the bottom line, let's go back a half a step. You make decisions based on predictions. I predict that saying yes to being on your show is going to be a good thing. I say yes to your show rather than do something else with the time.

Turns out that predictions are illusions. In The Mindful Body, remember I said to you that it started off as a memoir. So, I have this story about my interaction with Hells Angels and I'm not going to give it away, but it was harrowing to say the least. That at each moment in the book when I'm telling the story, I stop and I said, "Okay, what would you do?" After the fact, it's very easy to know what to do. And we all know the expression "Monday morning quarterbacking," but we really don't realize that with respect to everything.

Two people arguing at a party. If I asked you right then, "Are they going to get divorced?" Who knows? People argue. Now, if I didn't ask you that, and the next day you find out, "Hey, they're getting divorced," you say, "Ah, I knew it. You should have seen them go at each other at the party."

I use this example in the book with my graduate students in a seminar in decision making. I tell them, "I have taught a version of this course for forty years. I have never missed a class. Am I going to be here next week? Predict." So, we go around the room, and these are Harvard students, so they say silly things like they say, "97 percent," because they know they're not supposed to say 100 percent. But so essentially, they all say, "Yes, I'm going to be there."

I say, "Okay. Now, let's go around the room and each of you give me a good reason why I won't be here." The first one always says, "For forty years you've been here, you deserve a time off." The next one says, "Your dog has to go to the vet." The next one says, "Your car got a flat tire." And they give me twelve, fifteen good reasons why I won't be there. I said, "Okay. What is the likelihood that I'm going to be there next week?" And now, that 100 percent drops to 50 percent. Going forward, we have no idea. Looking back, it's quite easy to make everything make sense.

All right. So, if you can't predict whether you're actually going to like this thing, we're trying to decide which restaurant and one restaurant was a restaurant I've enjoyed in the past, but that doesn't mean I'm going to enjoy it now or anymore. My tastes have suddenly gotten more sophisticated or whatever.

So, the way we think we should make decisions is that what's going to happen, what's good or bad about different outcomes. You add them up in some complicated way and then you do what that cost-benefit analysis leads you to do. Wrong. Nobody does it. It doesn't make sense to do it. So, what's the bottom line? Okay, Guy, you tell them what's the bottom line?

Guy Kawasaki:

This is a test. I'm getting tested by my Harvard professor. The bottom line is we go to this restaurant, it has terrible food, and we make the best of that decision, which is, "Oh, we won't stuff our faces. Oh, we won't oversleep. Oh, we won't get a hangover."

Ellen Langer:

No. That if the food isn't so good, we get more time to enjoy each other and to seriously think about what the other person is saying. So, the upshot, since you can't make the right decision, is to make the decision right. You could flip a coin, and we did this. I had people spend a week not making any decision, just the first option that comes to mind, do it or flip a coin or roll a dice, whatever it is you want to do. And at the end of the week, "How was it?" "It was great. I didn't have to worry about making a decision."

Then I had another group, I said, "Make everything a decision." And, "Should I put my right sock on first or my left sock, my right shoe, my left shoe." And at the end of the week, they also had a fine time because part of the stress that comes from decision-making is that we don't make that many important decisions.

So, if I gave you an exam and you had one question, that's a little scary because you get that question wrong, you fail. If you have 100 questions, you can make a few mistakes and it doesn't matter. And so, that's why making a decision every minute also puts each decision in a different perspective. But people should try it. Just randomly choose whatever it is, because you can't know because everything is changing, everything looks different from different perspectives. Prediction is an illusion. And whatever it says, do and make it right.

And data for this comes from some other people entirely different on regret that people tend to regret the party they didn't go to, the whatever it is that you're rejecting. Because once you accept it, you make it work. "Oh, gee, it was a good thing I was there and Guy and I got together and we had a wonderful conversation. He's a surfer and I learned all about him. And if I didn't go, I wouldn't have that information," that I'm eventually going to use to tease you with.

Guy Kawasaki:

I kid you not. When I read this sentence, "Don't try to make the right decision, make decision right," I swear to God, Ellen, that was like the light went on. It was a turning point in my life this morning. I'm not exaggerating. That is humongous ramifications. One right in front of Madisun and I right now is we're writing a book based on this podcast about how to be remarkable. And we have three names as the final candidate, The Remarkable Way, How to be Remarkable, Think Remarkable like the Apple ad.

And after I read your thing, I said, "You know what? We're just going to pick one. And rather worrying about whether the decision was optimal and right, we're going to make the decision that we made the right decision." Yes? Isn't that the application?

Ellen Langer:

Yup, that's right. Now, so if you like one-liners, I have two others that are useful. The one that probably most useful since people suffer stress, and I think stress by the way is the major cause of illness. That if we took people who all just found out they had cancer, any kind of cancer, now nobody's going to be happy about that. But let's say three weeks later we start measuring their stress level over and above nutrition, genetics, everything, I think that stress would predict the course of the disease.

Okay, so here's the one-liner. Ask yourself, is it a tragedy or an inconvenience? It's almost never a tragedy. I missed the bus. The dog ate my homework. I couldn't finish the report. And once you ask that, you sort of just relax. And the other is that I don't think people will get as much out of this, but I think it's important that we have to stop using yesterday's solutions to solve today's problems.

Guy Kawasaki:

Which means what?

Ellen Langer:

Which means that everything we're doing, everything we decide to do is based on what worked yesterday. And so, what we need to do is sit up and pay attention now. So, when you're hiring somebody in, I don't know, managers or anybody in business, everything you're doing is based on the world as it existed last week, not tomorrow. And so, I think that what we need to do is hire people who are mindful or teach them to be mindful because that's the only way we can take advantage of all of the positive changes.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, in a sense you're saying, "Hire the best athlete, not the proven athlete."

Ellen Langer:

I'm not saying anything about an athlete. I'm saying even with an athlete, that if we had five athletes that we couldn't decide which was the best, I would hire the one that was most mindful because they're changing their performance ever so subtly rather than saying, "Oh, now I've got it and just keep performing in the same way."

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, my last question and probably not your last answer, but my last question. After I read your book, I have come to the somewhat semi-facetious conclusion that the best case is that I or the listener or the reader not have read the book, but my friends and family have. So, my friends and family have read your book. They learned about placebo. They learned about variability. They learned about uncertainty. They learned all these great concepts and now they apply it to me because now that I read your book, I know all these things and I'm thinking, "Oh, is this the placebo effect? Is it real? Am I doing the decision wrong?"

So, it would be better if people around me knew all this thing.

Ellen Langer:

No. I write these books because of the deep belief that the world will be better, my life will be better once everybody becomes more mindful. And an interesting part of the book is some of the new work that's wild, I'll just take a minute, just talk about it, about mindfulness being contagious. If it turned out that your family and all the people around you are mindful, you would end up mindful whether you wanted to or not. So, that's good. That means in our hiring, we don't have to make sure to the one, the person is mindful.

But I can't say given that when you're not mindful, you're not there. And my belief is if you're going to do it, you should be there for it. And being there for it should be fun. Why? You would want just the people you love to become more mindful. I don't know if you saw it. I think this is a great video. It's called Piano Stairs. And people who did this in Scandinavia, I don't remember just where, but they went down to subways.

And in many places, as we have here in this country, you have an escalator and stairs. And they videotape this and everybody's taking the escalator. Only a few young boys take the stairs. Then what they did was they put down a piano keyboard on the stairs. As you're going up the stairs, you're making music. Okay, now in almost no time at all, everybody gets off the elevator and they're taking the stairs.

And what I say when asked if I'm talking to an audience or tell my students, why wait for somebody to put a keyboard down that we can make virtually everything fun and interesting and meaningful. And again, I say, if you're going to do it, be there for it or don't do it. I tell my students, if they're going to write a paper, if they're not going to find it interesting, make it meaningful to them, don't write it. Life is too short. And they know this.

We have now different from when you and I were younger, we have all of these people like Jobs and Bill Gates, who dropped out of school and did just fine. They know that if they're going to be in school, they don't need to be there, make it matter. And I think now with AI, there's this big thing at Harvard probably in schools around the country, oh, my goodness, AI, ChatGPT-3, 4, 5 can write the paper for them. And so, what if they all cheat?

And I think that we don't want to prevent people from using technology that's extraordinary. What we want to do is to teach them how to use it so they prosper from it. And just letting somebody else write your reports, you'll get the A, but you'll never feel good about yourself. And the downside also with Chat is they'll say something that's wrong and you'll have no idea and that will be the end of your career. But who am I to speak on?

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, as an aside, I will tell you that ChatGPT and Bard and Claude, which is the big three that I use, there is no doubt in my mind that they have made me a better writer. And I don't tell it to write my book. I use it as a research assistant.

Ellen Langer:

No, and I think it's extraordinary. And so, let's say you were hiring right before any of these came on market. The person you're hiring would not necessarily be the same person you'd hire today, now that we have chat to do it, for example. And the same thing with tomorrow. Things are always changing. And so, I think that we want to hire the people who can accommodate, appreciate, be aware of all the change and facilitate that in other people.

Guy Kawasaki:

And what if somebody says, ChatGPT and AI is going to be the death of mindfulness because it's going to make people not have to pay attention and just put in a prompt and not even think about it.

Ellen Langer:

Yeah, I can't imagine that that would be so. And people are ever so resourceful that if Chat were able to do all of your work, hopefully, I'm sure the people who are more mindful would then spend their time in other meaningful ways. So, for me, I paint, I play more tennis, I do lots of activities that I enjoy as well as I enjoy writing books and teaching.

We had one where we were going to have, we didn't do this study, but tell me what you think of it. We were going to have people who have learning disorders, disabilities choose a person who they would like as their teacher. So, Guy, you might want Jerry Seinfeld to teach you. And so, Chat would take the lesson and teach you as if he is Jerry Seinfeld. And I think then you'd learn better, that all of us are capable of learning once we put aside the diagnoses we've been given and our thoughts of ourselves as being less than we might otherwise be.

Guy Kawasaki:

If we come to that, I'm going to pick you and Carol Dweck and Phil Zimbardo as my teachers.

Ellen Langer:

Okay, that's great. Carol and I went to graduate school together and Phil Zimbardo taught me psychology.

Guy Kawasaki:

I was Phil Zimbardo's Psych One proctor at Stanford.

Ellen Langer:

Oh, okay. Yeah. And he is an incredible teacher.

Guy Kawasaki:

He was the best.

Ellen Langer:

I can tell.

Guy Kawasaki:

I think I got as much as my little brain can handle. So, now, just pitch your book one last time.

Ellen Langer:

This book is a culmination of my research over forty-five years on mindfulness without meditation, that essentially shows through lots of research how everything is mutable, everything can be changed to make it work better for us. That even our diseases, that once we put the mind and body back together, we have enormous control over our bodies. And that sets us up for enormous control over our wellbeing.

Guy Kawasaki:

And may I just say that every parent needs to read this book. And I'm being repetitious now. But I will tell you, this sentence, which I have bold faced on my notes, is "Don't try to make the right decision, make the decision right," is an absolute game changer in life.

So, there you have it, how your mind can impact many aspects of your life, including some that you would not have thought could be affected by mindfulness. This has been Ellen Langer, Professor of Psychology at Harvard University, her latest book, The Mindful Body, check it out.

Now, I would like to thank the Remarkable Team because, there's that magical word, because they make this podcast what it is. The team is Jeff Sieh, Shannon Hernandez, Madisun Nuismer, Luis Magaña, Fallon Yates, Alexis Nishimura, and Tessa Nuismer. These are the people behind Remarkable People. And don't forget our sponsor, Merge4, the world's coolest socks. Promo code, “friendofGuy”. Until next time, don't just think different, think remarkable. What a great title that would make for a book. Mahalo and Aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply