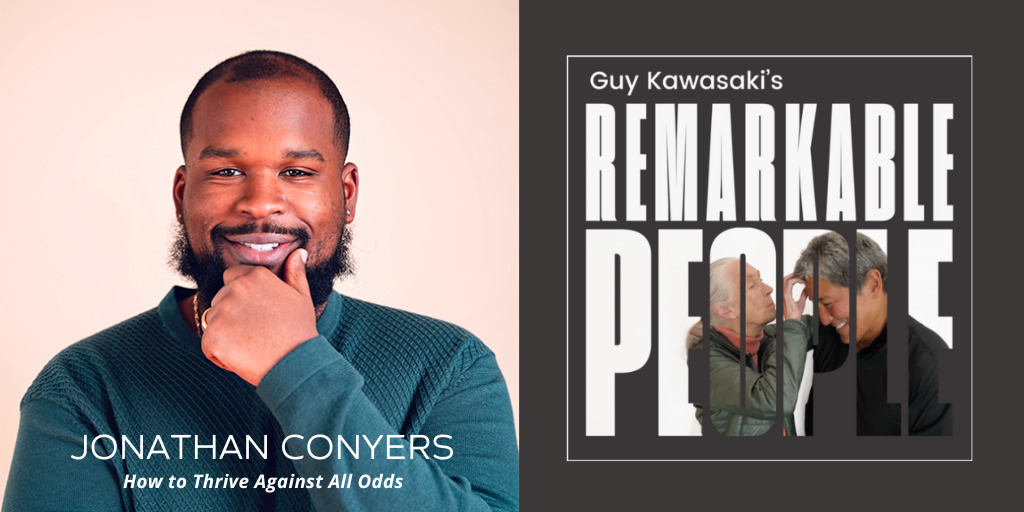

Welcome to Remarkable People. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Jonathan Conyers.

Jonathan is no ordinary individual; he is a force to be reckoned with in the field of education and healthcare. His journey from humble beginnings to extraordinary achievements is a testament to the power of perseverance and the transformative impact of truly remarkable educators.

Within his new book, “I Wasn’t Supposed to Be Here: Finding My Voice, Finding My People, Finding My Way,” Jonathan shares an incredible story of escaping challenging circumstances and highlights the transformative role of teachers, mentors, and guides along the way.

From struggling to read to becoming a breakout star on his high school debate team, Jonathan’s life-changing friendship with his transgender debate coach, DiCo, played a crucial role in shaping his future. In fact, DiCo makes a special appearance at the end of this episode that you don’t want to miss!

Please enjoy this remarkable episode Jonathan Conyers: How to Thrive Against All Odds

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Jonathan Conyers: How to Thrive Against All Odds

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. We're on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Jonathan Conyers from the projects in New York City where both his parents were crack addicts. To graduating from college and becoming a respiratory therapist, Jonathan's journey is a testament to perseverance and the impact of remarkable educators. He went from struggling to read to becoming a breakout star in his high school debate team. He had a life-changing friendship with a transgender debate coach named K.M. DiColandrea, AKA, DiCo. Jonathan's story was even featured in the Humans of New York series. I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People, and now here's the remarkable, Jonathan Conyers.

If nothing else, after reading your book, I have a ton of respect for respiratory therapists. I had no idea it's so hard to become a respiratory therapist. So my hat's off to you for achieving that.

Jonathan Conyers:

Yeah, respiratory is an awesome field. I think technically people still say it's kind of a new field. Nursing has been here forever. Respiratory therapists really came about, I think maybe I'm wrong here, but I'm thinking around the 1940s. So technically is a new profession and fortunately, but unfortunately, COVID really showed what we do as individuals who manage mechanical ventilators and are responsible for people's airway and to breathe. It was one of those things where the world really relied on us during the COVID pandemic. So yeah, it is a tough job. It's tons of responsibility to be able to manage somebody's lungs, to put tubes in babies, to put tubes in adults.

I know that sounds kind of ugh, but it's a part of our job. And I remember being at Stony Brook University, a professor telling me to hold my breath, and I held my breath and I couldn't breathe anymore. And he was like, "Stop." And he was like, "What did you think about when you couldn't breathe?" And I was like, "Nothing." He was like, "That is the essence of respiratory therapy is the idea that when you can't breathe, you can't think about nothing else." So doctors, nurses, nobody can do their job unless we allow our patients to breathe. So one breath at a time.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yup. And you got to save your mother's life?

Jonathan Conyers:

Yeah. That was a tough experience for me. I've never actually even shared that ever publicly. The people haven't got the book yet, but to be able to use my expertise and knowledge to help give her CPR and revive her when she was going through that difficult situation was tough and mentally draining. But it was also a remarkable experience as I think about it, to even have the tools necessary to help her in that difficult situation.

So yeah, it's kind of ironic because I wanted to get in medicine because of my mother's diagnosis of multiple sclerosis when I was nine. And I vowed to myself that I would work in medicine, that I will change lives, that I will help people.

So I'm sad to say that I haven't found a cure for multiple sclerosis, which I said I would do at nine. I don't think that's ever going to happen throughout my life, but to be able to help my mother in other ways. Like for instance, she has COPD and she has asthma, and to be able to understand the lungs in a very detailed way and to give her guidance and advice and to essentially have saved her life in that moment gives me joy of all the studying I did throughout college and in my current life.

Guy Kawasaki:

I majored in psychology. Maybe someday I can help somebody.

Jonathan Conyers:

The brain is very interesting and it's tough. You can help a lot of people.

Guy Kawasaki:

So how are your parents these days? It was quite the journey reading your book.

Jonathan Conyers:

Yeah, my parents, they're both still alive. I know most viewers haven't read the book, but in the book I talk a lot about my parents' journey with their addiction. I don't really have a concrete answer yet to say that they're clean or they're not clean. I think it's something they're still battling, it's something they're still trying to figure out.

But what I can say is that they are amazing grandparents. They have done better by their grandparents than they have by us, and as they were going through their journey with addiction and as they were figuring out some things in their life, but they are amazing grandparents. They have a lot more stability in their life, and I'm proud of them. I'm proud of them and their journey. I'm proud of them and their efforts to be better people, to be remarkable people.

And I'm happy we have these stereotypes and especially Black families that you don't speak, you don't say, you don't tell what's going on in the household. So for my parents, even in their age, to get rid of that myth and to create a safe space and be vulnerable and allow us to have these conversations, which is essential to our healing and my healing journey and my siblings healing journey, it says a lot about them and how far they've come.

So they're great. They'll be traveling. It'll be one of their first times on a plane next week. I'll be taking them to the Virgin Islands with me. So I'm excited about that to show them something bigger than the Bronx, New York for once in their life. So there's a whole world out there that they have no idea about that I'm excited to now in my life, be able to give them those opportunities and enter this new chapter of our lives.

Guy Kawasaki:

It seems when I was reading your book, you were surrounded by a lot of supportive people, a dozen or so, your village. But did anyone ever tell you that you could not succeed and you had to prove them wrong?

Jonathan Conyers:

Yeah. How can I explain it? So one of the things that's very important to say, just to give some backstory, is that the reason why I wrote the book was to show two things. It was kind of to show the idea of resilience and why resilience is extremely important. And two, was to talk about the idea of a village, the idea of finding people who may not necessarily look like you, who may not necessarily understand what you're going through in this given moment, but who can be guideposts throughout your life.

So my village was extremely important, and everybody that was in my village, whether they made the book or not, wasn't always supportive. There were people in my village throughout Stony Brook who gave me the drive when they said, "You can't work in medicine." Where, "Maybe you should major in English. Maybe you should major in history because you'll be insane to be a teenage dad with a baby on campus and think you're going to do medicine at such a top university."

Those were people in my village, even though those stories didn't make the book, I consider those people a part of my village because they helped build my confidence, they helped build my awareness. They put me in situations of adversity and situations of doubt, which I hope throughout the book I showed that in those moments I was able to overcome, and I was able to step up to any challenge.

So there were a lot of moments just being born into the life I was born into, being born into the type of parents I have, being born into the zip codes I was born into. My whole life was a walking idea of your less than because of the color of my skin, because of the type of stereotypes that came with being a child of two drug addict parents.

So yes, throughout my time in Virginia, there was a lot of people who put me to the wayside. The book talks about how I start off in special education where I couldn't read till third grade, and there were so many teachers who was willing to give up on me, who thought I should be a part of the system, who thought I should be another Black kid who will be a statistic.

So there was a lot of those moments. I felt like throughout the book, it was unnecessary to bring those people in the village because there was enough grief, there was enough pain, and there was enough hardship throughout the story. So I wanted to focus on the people who was trying to get me out of those places instead of giving light to the people who doubted me. I think the book is testimony enough that their thoughts and their doubts didn't matter.

Guy Kawasaki:

And would you say when they had these conversations with you, was it given in the spirit of I want to be realistic and help you, or was it like mean-spirited, racist, actually trying to put you down?

Jonathan Conyers:

Most of them was in the spirit of mean, racist and putting you down, and it was due to other people's perceptions on life, perceptions of what a Black kid who had made so many mistakes would do. People trying to find the idea of where to put their energy to. One of the things I talk about, like the idea of being a village member, I'm talking more on the positive side, is that people think that if you're a part of somebody's village, that you have to sacrifice your career, you have to sacrifice your life.

A lot of people are so afraid to say, "Hey, if I want to help you throughout my journey or throughout your journey, then I have to sacrifice too much or I don't want to commit to these things." And I hopefully throughout my book, there was a village member who was homeless throughout my book. It was literally a couple of sentence where I talked about the homeless man who taught me how to tie a tie.

I tie so many ties today. I don't know who that guy is, I can't tell you anything about him. But that one lesson he taught me, one, gave me confidence going into my first day of high school. And two, has carried over throughout my life where I'm constantly speaking and wearing suits and talking to individuals. So I felt like a lot of people who were negative throughout my journey, some of it did come across, I don't want to speak for them, I really don't know where it came from, but some of it felt like it was coming across as like, I don't have time to help you with your journey.

You have a rollercoaster of things going on. Sometimes you're high, sometimes you low, and they felt like putting energy into towards me or giving me advice or constantly checking up on me would've been too much for them, where it could have just been a positive conversation or just a life lesson, or here's a meal that would've made them positive impacts in my village.

So I think it's a tough question. I'm not for sure where those negative thoughts was coming from, but overall, I would like to say that a lot of people who are being mean or who are being negative or who don't want to be a part of somebody's village, it comes from a side of insecurity on their part or a side of the fact that they think they have to commit too much to help somebody throughout their journey.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, if that homeless guy had loaned you a belt, you would've had a perfect first day at FDA.

Jonathan Conyers:

It would've been perfect, but I don't think he had a belt. I don't think he had a belt, but it would've been perfect. It would've been perfect if he would've gave me a belt.

Guy Kawasaki:

A consistent huge theme in your book was about college, getting to college, and graduating from college and how that would be a life-changing, life trajectory improvement, et cetera, et cetera. But recently, lots of people, I might add mostly white and rich, say that college isn't necessary or sufficient to succeed. And yet for you, I think it was an absolutely vital goal. So what's your take on the goal of going to college 2023?

Jonathan Conyers:

It's extremely important to go back to your comment about individuals of privilege who may not think going to colleges necessary. I don't want to dismiss their feelings. That may be truly accurate for them. When you come from a situation of privilege, when you come from a situation where maybe dad can invest into your first business, maybe you have had conversations your whole life since you was five at the dinner table of how to be an entrepreneur, of how to run a company.

When you have been molded and got some of the best private school educations in the world and is already at a certain level within your life of knowledge and connections and networking, then maybe college is an unnecessary investment for them. But as a Black kid who grew up extremely poor, who grew up to drug addicted parents, who grew up in some of the most dangerous areas in the South Bronx, who went to middle school where you had to worry about metal detectors and gang violence, and you go to a school where the reading level is 7 percent for the entire school, college is a necessity.

College is more than just that piece of paper. It's about development, it's about finding yourself. It's about learning how to network. It's about knowing how to thrive in different communities and learn from other people and take in so many different information. So for me, in 2023, in 2030, in 2040, trying to predict the future here, but people of color and people who are going through stressful situations and who may not have that guidance or people in their life to set them up for success, you have to start somewhere.

And that start is the foundation of your education, that start is the foundation of getting a college degree, and that start is getting the tools necessary so you can be in these rooms and show people how special you are, and how your upbringing don't define the trajectory of your life. So I will forever be a huge advocate of college and getting your education.

Guy Kawasaki:

Amen. Amen. So now suppose you are a rich white kid at Andover and it's the summer and you encounter the (MS)2 students. And maybe some of this is just pure ignorance, but what would your advice be to that rich white kid when they see a bunch of Black kids at Andover, clearly different economic status, et cetera, et cetera? What do you tell that white kid?

Jonathan Conyers:

Use them. I would tell them to use them. I think a lot of times in college I thrived so much. At (MS)2, I thrived. And I think a lot of times a kid of privilege, a kid who thinks they have it all figured out, a kid who thinks wealth defines their journey and their development as a person has misunderstood. I think one of the things that happened to me throughout my life was that I always assumed that I was less than. I always assumed that I didn't have what it takes to thrive at a Andover. I didn't have what it takes to thrive at a Stony Brook University.

But when I got there, I learned something very, very, very interesting. That it was one thing that separated me from all of them, that made me thrive and do better than them was resilience. And just to bring it back to the book, the book is made to talk about resilience, is made to talk about the idea that if you can get through adversity, and I don't care what color you is, I don't care about your sexual orientation, I don't care what pronouns you go through, we all at some point, rich, poor, we all at some point have to be resilient. We're all going to face a challenge that money can't solve, that your connections can't solve, where you got to wake up and you have to do what you have to do and you have to overcome something that's very hard.

And being poor and being born into the lifestyle that I was born into, it gave me that resilience. So every time adversity knocked on my door, every time there was a challenge, I was able to go through it. I had a lot of friends that today I talked to that went to Andover, I had a lot of friends at Stony Brook who came from wealthy backgrounds, and there was a lot of times where we're in our science courses that anxiety would overcome them. They would be so stressed because they didn't know how to respond to certain type of adversities.

I would tell any kid of privilege at Andover who's in a summer session program and who's not a part of the (MS)2 program, which we can give more detail about later, that learn from those kids, learn from those kids who are resilient, learn from those kids who are standing on the same boarding school as you, who are going through unimaginable things at home, who are facing things that is difficult, that the majority of the world can't overcome.

That's their superpower, that's their gift. The fact that they're resilient in the fact that they are there and the fact that they're sharing that same space. And I would tell the Black kids who are from the south side of Chicago, who are living on reservations, who are Black and Brown kids from Baltimore, New York City, which are most of the kids who make up (MS)2, from Texas that use those kids also, pick up on their habits.

The first time I heard of The New Yorker, the first time I started worrying about the New York Times was watching kids in summer session, rich wealthy kids at Andover read them. And I said, "Why do they read that paper every morning?" And then I also told them, don't be intimidated because when their back is against the wall, I'm taking you any day over them.

So I would tell both groups and both audiences to learn from each other, to accept each other, and to go back to the idea of village, one of the interesting things about my book is that my village was comprised of so many different types of characters, so many different types of people. There weren't just a bunch of Black men because I was a Black boy.

And no, it was all different groups of people who taught me so many things about life and about their cultures and about their circumstances that gave me the tools to thrive. So I think we all have something to learn from each other. I think being open to differences, being open to different ideologies and people's way of living is what is really and truly going to continue to make the world a better place.

Guy Kawasaki:

Arguably, you are the world's greatest expert on building a village if you don't inherit the village. So what are your recommendations and tips about how to build a village? Maybe Hillary Clinton can learn a few things from you.

Jonathan Conyers:

Great question. Yeah. If Hillary wanted to talk to me, I'll take that conversation every day. I think I could learn some stuff from her also. But one of the most important things is to be open. People in your village don't have to look like you. And I think that's the problem with most people who are trying to assemble their mentors and the people they want to look up to. If you think about my college counselor who's a mother to me, who I love, Pam, who I talked about in the book.

If I would've looked at Pam as just a little person with a disability, a person who didn't understand me, a person who was going through their own fight and had their own community that they love and support, I would've missed out on being a respiratory therapist. I would've missed out on the opportunity to save my mother. I would've missed out on all of the life lessons this wonderful lady has taught me about how to be a better father, about how to be a better student, about how to balance twenty credits and two jobs.

If I would've looked at DiCo who was trans and changed his pronouns and said, "This is who I am, Jonathan." If I would've said, "Well, I'm Black, I have my own fight. I don't want to know about the problems that's going on in your community, I don't want to accept you for who you are because of this ‘ism’ or this ‘ist’ or whatever box I'm trying to put somebody in," then I would've missed out on one of the most brilliant minds I've ever met.

The Brooklyn Debate League wouldn't exist right now. I would've never got to debate at Harvard at the level I debated at. I would never now not be standing side by side with this individual creating speech and debate programs throughout New York City for at-risk kids. So there are so many people throughout my journey, especially a lot of people who go through life and say, "All right, I like violin. Guy is an awesome surf boarder. What can Guy teach me about anything? I want to work in medicine."

Guy Kawasaki:

That's a good question actually.

Jonathan Conyers:

Yes, Guy is a tech genius. He loves marketing. He's very good at selling himself. What can Guy teach me? Well, Guy can teach you about how to work hard. Guy can teach you about a podcast. Guy can recommend some books to you that may change your life. Guy can just smile and give you positive energy and create positive content, and that could be enough to get you over the hump.

One of the things that was so interesting to me when I was just doing my audiobook, and one of the things about my audiobook that I loved so much was that I got to bring characters from the book, and we created bonus content. I let them explain their side of how they were interpreting the book and what they did to my life and my true feelings on what they did for my life.

And Francisco, who's a character in the book, he comes in and he's like, "Jonathan, I know you're amazing. We knew that since you were a kid, but I don't know why the heck you invited me here. I didn't do nothing for you. I'm not a part of your village." And I smiled and I said, "You've been in education for over fifteen years, which is one of the hardest jobs in the world, and you have no idea that you're a role model. Your presence and your openness to tell true stories is getting kids through so much difficult times in their life."

For him to come to me as a Black man holding a baby about to enter freshman year of college as a teenage dad, and to say, "I've done this. I have done that, you'll not use your daughter's existence as an excuse. Instead, you'll use it as motivation to be the best because all these other kids have time to play. You have a mouth to feed. You have to be the best. There's no what if. This is a necessity for you."

That ten to twenty minute conversation sparked something in me that changed my life and that made him a part of my village. He didn't buy my kid Pampers. He didn't show up to my door every day at 5:30 in the morning saying, "Can I babysit her?" No, it was a conversation. It was him being vulnerable. It was him saying, "This is how I'm feeling. This is what I went through as a single dad on the same college campus that you on and I did it, and now you can do it. Good luck kid."

Guy Kawasaki:

Yep.

Jonathan Conyers:

And then that's how you build the village and that's what's important. There are so many people out here who want to do right by people. I know media, I know the news, and everybody's always highlighting all the negativity that's going on in the world. We're constantly trying to be divided in so many ways. My memoir is not just your typical Black boy make it out the hood story. It's a story of inclusion. It's a story of coming to action. It's a story of why affirmative action matters, why the decisions of the Supreme Court is invalid, why it doesn't work, why different communities and people of different communities can come together and help save and change lives.

It's a book that shows that drug addicts shouldn't be displayed in a certain way, that people who are addicted to drugs still can be caring, still can love their kids, still can defy odds and teach about education. It is so much to it, and part of the village is really showing that it is up to you to find people who are willing to support you no matter what they look like, no matter what they believe in. And it's very important for all of us to dig deep and find our village.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. So I also consider you an expert in how to ask and accept help. So give us the gospel according to Jonathan about how to ask for and accept help.

Jonathan Conyers:

Closed mouths don't get fed. It's simple. I've heard that my whole life. Closed mouths don't get fed. Pride is the devil. We are so prideful. We have to create this false image, and especially for my generation, this idea of creating this false reality of who you are and this perfect picture of your life, through pictures, through Instagram, through Facebook, we get to create this false reality in real time.

And we don't understand that the power of vulnerability, the power of asking, the power of yearning for knowledge and asking for help is what makes the world go around. Collaboration is important. Going out there and telling the world of what you need and leaning on your elders and people that are wiser and have lived life longer than you is what's really going to carry you not to just being successful, but to creating longevity, which should ultimately always be the goal.

And that's really what it's about. It's just about being able to say, I need. Why should we suffer in silence? Why should I hurt myself or hurt my family because of something I made up in my head or this stigma or this trauma that's not allowing me to escape and scream and say, "I need help." There are so many people out there that want to help.

I just recently said that there's so many people out there that want to do good, there's so many people out there that's yearning to give back to their communities, and I was blessed to understand that at an early age, and I was blessed to find those people who were willing to do it. And throughout that journey, yes, your pride may be hurt. Somebody may say no, somebody may be having a bad day.

But I had goals and that's one of the things, I never did things with blind faith. I always found the task even to the day. I found the task. I obsessed over that task, and it was never about the in-between. It was always about how do I get to that task?

So whatever Jonathan needed to do to get to that task, I was willing to do. And a lot of that from a kid who didn't have resources, who didn't have the mentors and the role models early on. And being an intern of life where there was substance and things that can carry me to that, I had to find those people and I was willing to do it. And that's why asking for help and finding those people is crucial.

Guy Kawasaki:

And how do you decide who to believe? Case in point, Tyson. You chose not to run with Tyson, but many Black kids in general pick the wrong people to believe. So with hindsight, how do you decide who to go with, who to believe?

Jonathan Conyers:

Well, in the book I did believe Tyson, I did believe RJ, but people always think that your village members are always positive role models. Some of my village members was drug dealers. Some of my village members told me what not to do. Some of my village members gave me the blueprint of what my life would be like if I kept going down this pattern and I made mistakes. I was a kid.

A lot of me assembling my village was luck. I'll be irresponsible to say it wasn't luck. And a lot of me developing my village members was going through bad situations and taking some of the lessons they had and trying to use those lessons to show what I didn't want for my life. Some of my village members was there for a short period of time just for survival. I knew they weren't good people. I knew they weren't doing the right things, but I knew I had to rely on them to survive in that moment in my life.

And I prayed very hard that in those moments of survival, I didn't jeopardize my life forever. And I came very close, Guy. I came very close to jeopardizing. And I'm here not just because of my village members. I'm here because of the grace of God. I'm here because of luck. And I'm tired of people in my community always having to be lucky, which is another reason why I wrote this book. I wrote this book, one, to show that I am not an exceptional person and I know, I know.

Before you say, you may say, "Jonathan, I read the book, you're definitely an exceptional." And here's what I would say to that. Here's what makes me "exceptional." I was able to listen. I had people in my life that said, "Hey, you need an education." I showed up when adults that were smarter than me asked me to show up. What is exceptional about that? That is something that every person innately has in them.

I wasn't born with special DNA; I wasn't born six feet eight inches and can jump over a hoop. I wasn't born with God gift genetics. I was born with grit and resilience. I was put into spaces because of my zip codes, because of the people and things that were going on in my community, because my family was not in a position to give me the things I needed at that time and my necessities.

So I had no choice but to be resilient. I can take you to any neighborhood in the Bronx and show you 1,000 resilient kids. This book was shown to give them the blueprint to say, "Hey, you don't have to struggle. You don't have to think Tyson's your only option." Maybe listening to RJ sooner would've helped me not be in that situation with the law, not be on those corner selling drugs.

So that is the message of the book. How do I show you kids through my trials and tribulations that you can have a better life by just listening, to just loving people and opening your heart to people who may not look like you, who doesn't understand our community. I know DiCo didn't understand what it was like for a kid to go through a metal detector every day in sixth grade, or to be a Black boy in the South Bronx.

I know Pam didn't understand what it was like for me to go through those things, but they understood things that I needed that will get me out of those situations. They understood what going to college was like. They understood what being successful in college was like. They have seen thousands of kids like me go through the system and come out.

So I just had to rely on them. I just had to listen, and I don't want to make it seem like that's easy too because so many kids who are hurting, there's so many Black and Brown kids who are hurting who need to understand that it's the little things. It's not the big things. Mommy don't need a lawsuit. Nobody needs to win a million dollars. It's looking for people in your community.

Every community has them. I don't care what's the crime rate. Every community have some group of powerful ... And superheroes, which are our teachers, which are our counselors, which are our community advocates that love people and that want to help, and that have a wealth of knowledge that they want to give.

We just have to tap into our kids and show them the walking proof. There's not a lot of people from the South Bronx that end up being Jonathan Conyers and I understand that. But now I want to go back and show them that I'm no different than you. I grew up in these same areas. The only difference was I was willing to do whatever to assemble my village, and I was opening to listening and following directions. And I think that's important.

I also think it's important from the adult side. This book is also for the adults. It's also for people like you Guy to read it and say, an act of kindness, bringing remarkable people on this platform and creating healthy dialogue. You're becoming a part of people's village without you knowing it. There's going to be people who watch this and say, "Hey, maybe I want to read Jonathan's book. Maybe I love his journey. Maybe his journey makes me want to be a better teacher, makes me want to be a better person, makes me want to give a homeless man a meal."

I watched an episode with David Ambrose, he called me and he was like, "Jonathan, I'm a part of your village now" and we've talked about these things. I've never met David in person, but now he's a part of my village. It's the conversation. And that happened through the book world.

It's the conversations, it's just picking up the phone and the act of kindness where you could become a part of somebody's village. And adults need to understand that even more than kids. Adults really should be reading this book. People that want to do good and to understand that just a smile on your face, just the, are you okay? Can get somebody from going off that ledge and being the best version they need to be that day.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow, Jesus. So Jonathan, let's suppose that there are kids listening to this, and you had an extreme case, both your parents were crack addicts. But what's your advice to kids when they're in that kind of setting, and how do they break out of the cycle?

Jonathan Conyers:

It's hard. Guy, it's hard. I don't want to sit here and be irresponsible and make it seem like I have the recipe for how to survive drug addict parents. I don't. But one of the things that really helped me was my ability to dream. My ability to dream in the dark. My ability to believe that there was something out there that I knew I couldn't touch, that I couldn't grasp, but just to know that there was better.

My ability to be open. One of the most difficult things about this book was I wanted to forgive my parents. I wanted to learn more about them. And by learning more about them, I learned how remarkable they were. And I think a lot of kids who have parents that are on drugs fall into the trap of the stereotype, fall into the trap that their parents are beneath them, that their parents are less than, that their parents are not worthy of love and respect. And I was one of those kids before.

But to learn that my mom sang at the Apollo, to learn that my mother was a junior in nursing school when she got addicted to drugs was so good to feel. To learn that my dad almost won the Golden Glove Boxing Champion in New York City, to learn that my dad graduated from high school with a 4.0.

Lightning doesn't strike multiple times. If you look at me and my siblings, all of us are doing well in life. My parents raised five kids, both was drug addicts, and yet all five of their kids have degrees, all five of their kids are homeowners, all five of their kids are out there changing the world. I have multiple brothers in education. Two of us is in medicine.

There were beautiful gifts about my parents and they passed us on work ethics and mindsets. My mother always tell me, "What would I have been if I didn't get addicted to drugs? Look at my kids. You guys are the recipe of what my potential can be."

And although I am thankful and I'm happy that my kids turned out okay, it hurts her to see that maybe she could have been a CEO, that maybe she could have been executive if she didn't get trapped into a cycle that I don't want to come here and sound like an expert, that was forced into her communities, that was a part of a bigger plan that I believe, within the Black community.

So what I would tell those kids is that one, you have to find your village because you're born into a place where the people who are supposed to provide for you, the people who are supposed to protect you just cannot. And no matter how much they try, even if your parents love you, that drug will consume them, and it will make their reality a forced reality.

And they won't be able to give you the things you need that every parent should be able to give their child. And I'm not talking about a fancy vacation, I'm just talking about the basics. Shelter, food, conversation, warmth, love. It don't take a lot to give those things, even at the lowest level. And my parents, they were struggling to give some of those things because of what they were going through.

So I had to rely on other people, whether it was my siblings, whether it was village members, and I had to find ways to release that frustration and anger. And I didn't always do it right. You'll see throughout the book, a lot of times I made mistakes, but I never gave up hope. I never stopped dreaming and I believed and I created deadlines. I created goals to force myself to believe that I can get out of what I was going through. Even when deep down inside, I didn't see a way out, I felt trapped.

So that's what I would tell all these kids is to one, don't try to understand your parents or forgive them for them. Do it for you. You can't move on. You can't heal. You can't see clearly unless you decide to forgive them and understand them for you.

Two, survivors will survive. How do you use education? How do you use teachers? How do you use positive role models? How do you use people that are destroying your community as village members to learn what I should be doing and what I should not be doing? And the book is a blueprint for all of that.

And more importantly, it's not really on the kids, it's on the superheroes, which are the teachers, which are the people in the community, which is people who have platforms like yours, which is people who have platforms like me to pick up my book and read it and know what kids are really dealing with. DiCo and a lot of people read my book, had no idea of all those things.

There's things that I talk about in the book that my mom is going to find out for the first time, that she couldn't believe that she missed because she was so deep into her addiction that she wasn't paying attention to the things her child was doing. And I never had to explain to them that I was going through a lot. They just showed up and was guideposts for me every time I needed them to. And that was more than enough to overcome what I was going through.

So it's really not less about what the kids will do because the kids are going to be kids. They're going to make mistakes, they're going to lash out. It won't be a perfect story. It will be a drop, it will be a climax, it will be all over the place, it's going to be a NASCAR race. And it's up to the adults, it's up to the village members to put it into these kids' heads that they're special, to understand that when they lash out or they don't have a pencil for class today, that that may be because they didn't even eat dinner last night.

How could they focus on a pencil? To pick up on the social cues, to be willing to give a little bit of yourself to make the world a better place, and I think that's where the true responsibility come from. Not what kids should do, what adults should do to protect these kids. And I'm very fortunate that I had plenty of adults who was willing to protect me and fight for me.

Guy Kawasaki:

Can I ask you what you may consider to be a tasteless question?

Jonathan Conyers:

You can ask me anything.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah, you don't have to answer. But with hindsight, and you mentioned David Ambrose, what do you think would've happened if you went into foster care and the government broke up your family?

Jonathan Conyers:

So that's a great question. Me personally, I don't know. I wasn't in the foster care system. I was a foster care child briefly because my brother took me from my parents, which I talk about in the book, but I didn't go through the foster care system. So I don't know what it's like. I've heard stories. I know that it needs tons of work. I know that our nation has a lot to do with foster care rights and making that situation better for kids in that situation. But I don't have no lived experience of it.

So I don't know. I don't know what could have happened to me. I don't know what trauma could have came in my life from that experience. But what I will say, guessing based on the person I am, I probably would've found the best person in the foster care system where I was located. And then I probably would've found the worst person, made them a part of my village and used them to try better my life.

And I say that and I make that crazy guess because again, I'm resilient, and people that are resilient are the strongest and most gracious people in the world. And my resilience would've made me survive. I think I could survive anything. That doesn't mean I want to. I'm tired of surviving. I'm waiting for the point of my life when I could just live, when I could just give back, when I could just thrive. But I am a survivor.

So I think I would've survived. I would've learned as much about it as I can like David Ambrose is doing. And I would've went back and stuck it to them and tried to change the system, like I'm trying to change many systems that have personally affected my life.

Guy Kawasaki:

Like what?

Jonathan Conyers:

The juvenile system, drug addiction and how that affects people, the narrative of how that affects Black communities, the narrative that all crack heads beg on the street and don't love their kids and can't raise families. That narrative is changing due to the opioid crisis. But we know, I hope people know why it looks like that's changing because of the type of people it's affecting now. So I am trying to bring speech and debate to numerous communities.

There's a reason why I'm trying to do that. I think having a voice, I think creating a safe space for kids, I think kids being able to go into these rooms and have conversations about things that are affecting them, that are hurting their lives, being able to freely express yourself when you're going through a lot is important. So there are numerous things I'm trying to do to bring awareness to a lot of issues that's going on in the world and to make sure children and adults have platforms and a voice to speak up on things that are hurting them.

Guy Kawasaki:

So you mentioned this very briefly a few minutes ago, but there's this line of reasoning, again, primarily by rich white men, that affirmative action should go away, and these entitlements and like that kid you encountered in that first debate, "People in the projects, they're just taking the free money and they're living great lives and we should stop these social programs." And so all things considered, where are you on affirmative action and those kind of programs post this Supreme Court decision?

Jonathan Conyers:

Well, we want to get rid of affirmative action, I think we also should get rid of legacy. People with legacy shouldn't be admitted also. So if we're going to tear down the system. Let's tear it down and make sure nobody get any privileges. And also too affirmative action, yeah, maybe I was a product of it. Matter of fact, no, let me take that back. I was a product of it. Maybe I did get into college because of affirmative action, but I had to earn my spot there.

You can check the records, I'm pretty sure I did better than 90 percent of the kids at Stony Brook University. None of those grades was handed to me. I not only did it with one of the hardest majors, I did it as a father, I did it working two jobs continuously throughout four years. And I finished on four years with a major and a minor, and I just didn't finish. I excelled.

So affirmative action, it's not giving anybody anything. It's just stopping these individuals from being prejudiced and blocking the door and being gatesmen from letting us into these universities. And even with affirmative action, how many percentage of Black and Brown people are really at these universities? The margin is still so wide, we still have a lot of diversity issues in a lot of these Ivy League schools and a lot of these institutions. And it doesn't benefit the counterpart. You want people from all different walks of life to communicate with each other, to talk to each other, to learn from each other.

And anybody who thinks that I had any advantage in life, or to think that people in the projects are living luxurious lives, one, I am willing to give my email. I will give you guys a tour of Webster Projects any day, and you tell me what type of advantage I had in life. People that are parents now, it's hard and I'm adult with much more resources. I don't even know how I did it at seventeen. I think back, and how did I even survive that?

So affirmative action I think is important. And I think there's a stigma behind this, a stereotype where we're giving someone something. People still have to earn their spot at these universities. They still have to qualify to even be considered for these universities. What it does is it stops the machine and these individuals from blocking us out, even though we deserve to be there. And it's righting our wrongs. We have redlining. We have so many things that have set Black people so many years behind. And the people who have caused these issues and who have pushed this setback should be responsible for trying to help us at least lower the playing field.

And I hope everybody in SCOTUS picks up my book. I think they should see the type of kids that benefited from them, from affirmative action and what these individuals are doing in society once they're given a platform, once they're given the right tools to lower the playing field. And I think it sucks. It's a difficult time in our nation right now with so many things being stripped apart from women's rights, from all these issues with voting issues, from segregation, from books being banned.

It's like we're moving backwards so much and it's discouraging, but it's going to take people like me, it's going to take people like you and it's going to take an effort to continue to share these stories. Storytelling is what's going to save this. I really believe that. I think storytelling and sharing ideas and sharing real life experiences of why these programs and why these issues matter is what's going to change the narrative. We have to take back the story.

We have to show that affirmative action is not a handout, and the people that are benefiting from it are doing amazing things and deserve a spot at the seat. It's crazy that there's people on the Supreme Court that benefited from it, and they're a Supreme Court justice, so I would think they would know that it works. But okay. I'm not an expert in these things, but hey, it seems like they should be more aware that it works.

Guy Kawasaki:

Listen, at the very least, you should send a copy to Clarence Thomas.

Jonathan Conyers:

I would love to sit down with him too. I talk to anybody. And respectfully, everybody deserves dialogue. Everybody deserves a conversation and respectful, healthy dialogue. I don't know, you think Clarence will read it? I think he should. I don't know if I want Clarence a part of my village though, but God bless him. God bless him, honestly. I'm praying for him.

Guy Kawasaki:

I promise you that when your episode is ready, we will send a link to Stacey Abrams. I had Stacey Abrams on a few weeks ago and she is a remarkable person. Oh my God.

Jonathan Conyers:

She is the remarkable person. I am very aware that you had the wonderful Ms. Abrams on. I was actually sad a little bit because I was like, "Why didn't Guy interview her after me? I can't follow up Stacey Abrams," so I was a little sad. I was mad at you just a little bit. I was like, "I don't know if I'm going to let Guy be a part of my village after doing that to me."

Guy Kawasaki:

Jonathan, let me set the record straight. Stacey said, "You're having Jonathan on? Shit, I got to get on before him because there's no way I could keep up with him." I'm doing her a favor by putting her on before you.

Jonathan Conyers:

But that is amazing. If there's any way I can send Stacey Abrams a copy of this book, which I wholeheartedly believe that she will read this book and know that what she's doing and her impact aligns with what my book is. If we can get Stacey a link and I can get Stacey a book, that is more than enough. I appreciate you for doing that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Jonathan, with total certainty, Madisun and I can get her a copy of your book. We know this because we send her socks as we sent you, so we have her address to send socks. We can certainly send your book. We will take care of that, okay?

Jonathan Conyers:

You're the best, man.

Guy Kawasaki:

Actually, we should have it autographed by you and then you send it or something, okay?

Jonathan Conyers:

If she gives the green light, please. I wouldn't hesitate. I'll walk to Georgia to give it to her. Just let me know. It may take me some time, but I'll get it to her.

Guy Kawasaki:

We're coming to the end here.

Jonathan Conyers:

It's all right, man, take your time.

Guy Kawasaki:

I want to embrace a very important subject, which is how do you show gratitude to your village? In particular, this example where you wanted to get in touch with Mr. Marshall and he had died. How do you show gratitude?

Jonathan Conyers:

That's a great question. If you talk to most of the people in my village, they would show you that I'd show too much gratitude. When Mr. Marshall passed away when I was in ninth grade, it was one of its toughest things for me. I vowed to myself that in my blessings, I would never make it about me. I always will remind the people who have helped me, the people who stood side-by-side with me during some of my toughest times will know how much I love and appreciate them.

My story went viral for the first time, and a lot of people started to reach out to me. My Instagram blew up. I created a huge following after the Humans in New York story came out. The Humans in New York story was supposed to be about me, and I switched it. I made it about DiCo.

The reason why I did that was because the Brooklyn Debate League was going through some tough times. I could have selfishly just told my story. After you read the whole book, you know that the Human of New York story is barely touching iceberg. There is so much more in depth that nobody know and a lot of secrets that I told in the book.

But I decided to take that moment that I knew would be viral, that I knew Brandon Stanton, the amazing friend of mine, had this huge audience and platform, and I made it to highlight teachers and their impact. Because of that, DiCo's nonprofit, DiCo says it's our nonprofit. I'm the co-founder, but it's really his. But DiCo's nonprofit received $1.3 million off my story. That's how I show gratitude. Pam, I speak at Stony Brook University all the time. I was just their commencement speaker.

I do mentorship, I talk to students. I provide internships for the students at Stony Brook University through the EOP program, which stands for the Educational Opportunity Program. That's how I show gratitude. Malcolm, who was a character in the book, I've supported his career tremendously and gave him opportunities for him to express his art and acting career. That's how I show gratitude.

People in my village, the majority of them was in my audiobook. I gave them a five star treatment. That's how I show gratitude. I'm constantly reminding them how much I love them, how much I respect them and what they do. I think I'm overbearing. I could see they like, "Jonathan, stop. We know you love us." But that's the way I show gratitude. My blessings, I always try to share with them. I always try to give them opportunity.

I try to give them knowledge now of things that they gave me when I needed it. As far as the book world, as far as the podcast world, how do you do this? I have so many mentors and villagers who have their own ambitions that I never knew about because they were so busy trying to save me as a kid. Now as an adult, I can be their friends. I can learn about their story. I connect them to friends. I support a lot of their businesses. I invest in a lot of their businesses.

That's how I show my village members love and support. I also show them love and support. The number one way is by showing that their effort was not wasted. By waking up every day and being a good person. By showing them that the energy they put into me, the investment that they put into me was worthwhile.

Now I'm doing that for hundreds of students. That's the real essence of it. It's not the investment. It's not the money. It's not even the connection so they could chase their dream. It's the proof that all the work I put into you, Jonathan, was worthwhile. Because you are out there trying to change the world. You are out there paying it back forward to so many kids at risk who need your stories and who need your guidance.

I think that's the real true testimony. Even though I never got to tell Mr. Marshall, I never got to tell Dr. Hodge I love them and I appreciate them and all the yelling I did at them. It took a little while, but I understand now why they did the things they did. I hope they're looking down at me and saying, "Boy, all those fights with that young hardheaded kid was worth it." I pray that I'm living a good life and a righteous life for them.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow, that's a great way to end this podcast. But I have one or two more questions.

Jonathan Conyers:

Hey, Guy, you can ask me four more. Come on. We are having a good time, you don't got to end it. Don't worry.

Guy Kawasaki:

How do you measure your personal success? How do you keep score now?

Jonathan Conyers:

I keep score by how many times people tell me, "Thank you." I keep score by how many times people tell me, "John, this helped me. John, thank you for showing up. John, thank you for picking up the phone." My success is in the little things. In college at first and I was like, "I want to be a doctor. I want to work in medicine." It was all about money. It was all about living a lifestyle.

It was all about sticking it to them. It was all about showing them that this kid who had nearly a 1 percent chance of graduating college based on all the trials and tribulations I've been through was going to prove them wrong and make a boatload of money and have a gigantic house and do all of that.

Unfortunately, I haven't accomplished none of that, but it's okay. Is by the thank-yous. Is by doing right. Is by paying it forward. Is by being a great coach at the Brooklyn Debate League. It's by being a great clinician. It's by holding patience and holding parents' hand during some of their most difficult time. It's about showing up and not cheating myself, knowing that I'm doing right by everybody who comes across me, and know that I'm giving back and making a difference.

That's the true definition of success for me, making the world a better place. I'm in the early stages of it. I'm still twenty-eight. I don't know what these conversations have for me yet. I don't know what all the things I pour into my community has for me yet.

But I truly pray that years from now, I could look back and I could read one of my students' memoirs. I can have a student come back and give a speech for me at the nonprofit and say, "Coach, that conversation, that meal you bought for me, showing up to the courtroom when I was in a bad situation, letting me stay at your house for a couple of days when we got evicted."

I hope all of those things that I do makes them a better person, makes them have the life they dream of, and make them pay it forward to the next generation. That's how I measure my success. Right now, I'm feeling very successful at all the kids and all the amazing people I get to help.

Guy Kawasaki:

You can say no, but I hope you'll consider me as part of your village now?

Jonathan Conyers:

Guy, you're definitely a part of my village. Yes, I appreciate you for giving me the platform. I appreciate you for even creating a platform and a positive platform. I love a lot of crazy podcasts. Some of them are messy, but I love a lot of good ones too where I can learn something from it, where the dialogue is powerful, where the conversation means something.

Your podcast is definitely doing it. I hope my podcast can get to where yours is at one day, so thank you and thank you for even thinking about me. I don't think I'll ever be able to surf like you, but maybe I could do podcast like you.

Guy Kawasaki:

I have one last request. Do you know who Garrett McNamara is?

Jonathan Conyers:

No, I do not.

Guy Kawasaki:

He had a series called 100 Foot Wave. He surfs a 100-foot waves in Nazaré in Portugal. He's maybe the greatest big wave surfer. I asked him in his episode if he would someday tow me out at Nazaré and let me catch a wave at Nazaré. Thank you, God, that my wife has not yet listened to that episode. But anyway, you are wondering what the hell does this have to do with me, Guy? Here comes the relevance which is someday when I come to New York, I want you to give me a tour of the projects.

Jonathan Conyers:

Done.

Guy Kawasaki:

I want to see firsthand.

Jonathan Conyers:

Done. You'll be safe too, don't worry. Nothing's going to happen. I gave very, very wealthy friends tours before, family members. I'll give you a tour and introduce you to people in the community. We could walk and it's cool. Another thing is too, they call it the Joker stairs now. Remember the stairs where the Joker is dancing down those.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Jonathan Conyers:

I grew up right across the street from those stairs.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow.

Jonathan Conyers:

Yeah, my project building is literally across from those stairs. It was always funny, us in the Bronx, we get mad. Like, "Do you know how dangerous those stairs used to be? I ain't going to dance around there." But we could walk up the Joker stairs, we could talk. We could have a great time. My grandmother still lives there. It doesn't matter how well I do in life, she will never leave. We could visit grandma, too.

Guy Kawasaki:

You can just tell all your friends I'm Jackie Chan.

Jonathan Conyers:

They know you, Guy Kawasaki, you're famous enough on your own right.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now we are cutting to a recording of a phone conversation that I had with DiCo. I expected this to be a five, ten minute conversation about Jonathan, but we got deeper and deeper. I hope you enjoy what I intended to become a gray bar actually became an interview in and of itself. Here's DiCo. I interviewed Jonathan for my podcast, which is called Remarkable People. It struck me that truly you are a remarkable person.

DiCo:

Wow, that's kind of you.

Guy Kawasaki:

I just wanted to have a conversation with you too.

DiCo:

Well, that's very kind of you. Thank you.

Guy Kawasaki:

It's obvious. I happen to believe that as a profession, teachers are pretty much always remarkable. I have had great teachers in my life, so I want to express this appreciation for you and all teachers really to start off.

DiCo:

Thanks, Guy.

Guy Kawasaki:

Your story is so interesting. I obviously read it from Jonathan's side, but maybe you can tell me your side of how this kid is showing up in your debate club as a freshman and most of the people in the room are sophomores, juniors, and seniors. Can you just relay that story to us?

DiCo:

I certainly can. Would you like me to give a little the backstory of how I ended up in that room?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah. Absolutely.

DiCo:

Okay. All four of my grandparents were immigrants to this country. My parents both went to the local high school, and then my dad became a construction worker because my grandfather, his father, told him, "You have to work with your hands. That's reliable work." My dad ended up being on the construction team that built my high school, and I went to Stuyvesant High School, which is one of the specialized high schools in New York City you have to test to get into.

When I was there, it was a transformative experience. It's a phenomenal school, and really great teachers and kids. But the really transformational part for me was being a member of the speech and debate team. That became even more important after September 11th because my high school was located a couple blocks away from the Twin Towers.

I was sixteen at the time, and I was there. We saw the buildings on fire. I remember friends standing at the window and pointing and telling me that they could see people jump. I don't remember if I looked. I do remember running for my life. I remember thinking I was going to die. I remember in the months afterwards suffering from what I now recognize as symptoms of PTSD. The only place that I really had to process what happened and how I felt about it was speech and debate.

At those tournaments where I was showing up and talking about current events and real world topics and talking to my peers and also talking to adults who were judging those tournaments, it was my space to process this traumatic thing that had happened to me. To talk about why it mattered and to start to make meaning out of it. Two years later, I went to college. I was the first in my family to go to a four-year college. Much to my surprise, I got accepted to Yale University where I studied philosophy.

But had four great years there, mostly learning how to take care of myself and recover from PTSD through the help of some very compassionate and wonderful teachers and friends that took care of me. By the time I was about to graduate, I wasn't sure what to do next. When I looked at all the things in my life that I'd enjoyed, the common denominator was being around kids. I'd been tutoring every summer during the school year, and I loved teaching other people. I was a freshman counselor, I was working with younger students, and so I joined Teach for America.

My placement school was Frederick Douglas Academy, and that's where I met Jonathan. From the first year at FDA, the principal told me that every teacher had to run a club. He asked me what sports I had played and I told him rugby. He said, "Great, you're going to be our lacrosse coach." I was like, "Sir, I don't know how to play lacrosse."

He's like, "Whatever, it's a violence. It's the same thing just with sticks, you hit each other. I was like, "Dr. Hodge, look, let me start your debate team," and I did. We were a motley crew for a while that I didn't have a classroom. We were meeting in the culinary arts room. There was no budget. We were selling chocolate bars and Gatorades I was lugging in from Brooklyn to Harlem on the subway every day in some rolling suitcases.

But I remember by the time I met Jonathan; I think I was a third-year teacher there. We had a team at that point. We had a captain of the team, and we had been to Yale and Harvard and a lot of local tournaments, but also some national circuit tournaments. Dr. Hodge, because he saw that it was a successful program, gave me the chance to grow it by building classes into my schedule that were just for debate. In addition to teaching Latin, which is what I primarily taught at the school, I got a couple of debate electives.

Most of the kids who signed up for my debate electives were seniors because seniors have the elective blocks in their schedule. That made sense. Most of them were seniors, some of them were on the team, some of them weren't. But one day this freshman shows up at my door and he goes, "It's my lunch period. Can I just sit in on your class?" I remember being a little stunned because this was a high school, kids don't audit classes during their lunch periods. I was like, "What are you talking about? But sure, you can definitely sit in on my class. Here's a chair. Have a seat."

I wasn't sure what to expect. Maybe he was just going to sit there and be quiet. It wasn't like he was taking it for a grade or anything. But immediately this kid started speaking up and blowing everybody away. He was holding his own with these seniors, and it was not an easy class. They were reading Immanuel Kant. We're learning about deontology and consequentialism and John Rawls.

I have them reading Professor Michael Sandel over at Harvard, teaches a course on ethics and he wrote a book called Justice: What's the Right Thing to Do? I have them reading Michael Sandel's book. We're listening to the lecture series and watching it in class. It's a very rigorous class that is not just a passive thing, you could sit through it.

But Jonathan, he's doing all the reading. He's coming to every class. He's writing the papers. He's participating all the time. I say to him, "You got to join the debate team, man. You are so good at this." He joins, and again, he blows everybody away. He comes to all the tournaments. He comes to all the practices. He's a really, really smart kid. He's a kid that's just always got away with words. You can hear it now when you talk to him. I'm sure you heard it yesterday.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes.

DiCo:

But he's always been that way since I knew him when he was a thirteen-year-old kid. He's just got away with words. When he went to tournaments, he did really well. You can imagine my surprise at the end of the year when I gave the kids a chance to stand up and say what this class meant to them and what they're taking away from it because I like ending the year in full circle reflection way. You can imagine my surprise where John stood up and was like, "I joined the debate team to keep myself off the streets." We all looked at each other. The kids, me, were all like, "What is he talking about?" Then he kept talking, "I was at juvie last year."

We had no idea that this was a kid who had struggled in the way that he had struggled because he was just the nicest, most respectful, smartest, hardest working kid in that room. I remember looking around when he's telling us the story of what happened to him and how he was in juvie. How he joined debate to keep himself off the streets. Every kid in that room, their jaw was on the ground. Everyone was like, "Whoa. What?" You would never guess. You honestly would just never guess.

After he told us that and I learned a little bit about his backstory, I still didn't know the whole backstory because when I read his book a couple of weeks ago, I learned stuff and I was like, "Jesus, John. I didn't know that happened to you." It's incredible how resilient he is and what he's been through. But when I learned a little bit about his story, it made me even more certain that this kid belonged on the team.

It's not like our traumas were the same, because they're not. But I remembered when I was sixteen and trying to process terrible things that had happened in my life, speech and debate gave me the platform to do it, and how important it is for kids to have a place to use their voice to talk about what matters to them. Particularly in school where often what they're told is to sit down and shut up. They're not told to stand up and speak up about what matters to them.

It was important that we have this platform, so I was thrilled that John was on the team. It so happened that the following year, his second year on the team, when we were going to Harvard and he had earned a spot there because he was just such a phenomenal debater. The topic was about juvenile detention and whether juveniles in the system should be treated as adults or not.

I remember pulling him aside before the tournament started and I said, "John, there's going to be 400 debaters from around the country here. They're going to be the top debaters from the nation. But let me tell you, I guarantee you, you are going to be the only one who has ever experienced the juvenile detention system out of all 400 of them.

When you go into those spaces, I want you to remember that what you have to say really matters because you get this in a way that nobody else does." It was really special for me and for him to have that particular opportunity at that tournament to speak up about this thing that had been so traumatic for him as a kid.

Guy Kawasaki:

Then the irony is that when he lost that last round, the judge says it was because he used too much of his experience in his debate.

DiCo:

Yeah. That's something that unfortunately I have seen over and over again with many of my students in speech and debate. I think it's because people that are judging this event sometimes lose sight of the point. There's a lot of jargon and debate. There's a lot of technical stuff and words that you use and strategies that you use, and it's a very competitive sport. But for educators like me, and most of my coaches, my colleagues would agree at the end of the day, it's not about the jargon or the technical pieces or the language that you use, the strategies because kids aren't going to use that after debate.

No one is going to be talking about critiques and turns and spikes. That's all just jargon. What they're going to use after debate, we hope every educator hopes, is their voice. They're going to understand that what they have to say matters, and they can say it in any space across lines of difference to rooms of people that don't look like they do, that didn't grow up the way they did, or where they did.

And that gets lost sometimes at tournaments because people get caught up in the competition and in what they think the conventional debate is supposed to look like. And I understand there's value to conventional debate, but at the end of the day, the reason I do it is so that kids understand that their voices matter.

Guy Kawasaki:

I did not expect the interview to go like this. Oh my God, I think I'm going to go interview more debate coaches. My God, you're so articulate.

DiCo:

Thanks. I'm a debate coach, so I hope I know how to speak well. I'm working on it.

Guy Kawasaki:

If you are a work in process, oh my God, I would hate to see someone who's finished.

DiCo:

You should listen to some of my kids.

Guy Kawasaki:

I interview at least fifty or sixty very remarkable people a year. And this is like Jane Goodall, Margaret Atwood, Stacey Abrams. I have pattern recognition. I can recognize remarkable people, and you and Jonathan are both so remarkable. And from the outside looking in, what's the lesson of Jonathan? What can people hear about his story and say, "Huh, this is what I learned. This is how I can apply this to life"?

DiCo:

There's a lot to learn from Jonathan's story. I think people that have been through similar circumstances can take away that their circumstances don't define them. And even though all of society might be telling you that this is your destiny and this is your fate and this is where you belong, and this is what's going to happen to you, it doesn't have to happen that way. It's really up to you and the choices that you make.

And for those of us that were lucky enough to not have to go through the circumstances that John went through, I think the takeaway is to remember and to recognize the resilience of people who are struggling with serious traumas.

I'm a white person and I'm never going to understand what it is to be a person of color and especially a Black person in this country. But when I talk to somebody like John and I learn about his struggles that his family has faced and that his friends have faced whether we're talking about drug abuse, whether we're talking about mass incarceration, whether we're talking about the school-to-prison pipeline and being in schools.

A lot of his friends didn't learn how to read in middle school because it's such a failing public school. It just makes me really check my privilege and think about we have a lot of work to do to change the systemic oppression that is working to keep our fellow friends and neighbors and community members down. And that's I guess why I stayed teaching that there's so much at stake here.

We're talking about people's lives. And to me, and I guess probably John would say the same thing, the key is education. And I know that's what changed my life, and I was the first in my family to go to college. The trajectory of my life is different than my parents and then my grandparents and heaven knows the people that came before. And I imagine John would say the same thing. When we talk about education in this country, we have to remember just like when we're talking about speech and debate, it's not all about just jargon and strategies and concepts and things. Yeah.

Don't all those things matter? Sure. But we're talking about very high stakes and sometimes I feel like that sense of urgency gets lost and the human impact of this gets lost when we talk about education and kids suffer from that. Kids get lost in the shuffle, but we have to do better because there's a lot of Jonathans out there. I've met a lot of Jonathans in my fifteen years in the classroom and they deserve better.

Guy Kawasaki:

And how do you react when you hear people, primarily white male privileged, who say, "We should go to a skills-based perspective and the college degree per se is not necessary or sufficient"? You can interpret that as, yes, it's a better way of looking at the whole person. Or you can say, it's only because you're white and rich. You can say you don't need college. If you're Black and poor, you do need college just to break the barrier.

DiCo:

There are so many hot-button social issues right now that when you look at through this lens, your view might change. That's one of them. The extent to which college is not a nice to have, but a need to have right now. Another is, speaking of college, look at what happened just last week with the Supreme Court's decision about affirmative action. What about meritocracies? Like I said before, I went to Stuyvesant and my brother went to Stuyvesant, my other brother went to Bronx Science.

My siblings are products of the New York City Public School System and the specialized public school system. But I also recognized that my parents could afford to put me in a test prep program where I was able to study for that test and I got help. Not all kids have that advantage. And it's a problem right now that out of the 1.1 million kids in the New York City school system, so many of them are stuck in schools like Jonathan's middle school where kids literally were not learning how to read.

When we talk about the meritocracy and what's fair and should we have SATs and should we just look at test scores and how do we figure out who gets the spots at the best high schools or the best colleges, it's not as simple as that. I'm not saying that we throw the baby out with the bath water and there's no tests and no scores and whatever. I'm saying that number one, there needs to be a balance and that we need to be looking at the whole kid and their whole story and what challenges they're facing and that they've overcome and that they're working on.

And then number two, that when we move forward as a society, we need to remember that it's in everyone's best interest for everyone to have the best shot possible. Maybe instead of focusing on who's in the top schools, maybe we focus on what's happening at the other schools. Instead of lifting the ceiling, how about we lift the floor?

How do we ensure that every kid regardless of what zip code they were born into, or what school they were zoned for, or how much money is in their parents' bank account has a decent shot of getting the skills that they need to do better than their parents did, and to live their lives in a way that everybody would find acceptable? It's complicated right now. We're not doing a very good job as a society in navigating those questions, I think.

Guy Kawasaki:

When you hear a CEO say, "We're dropping the college requirement as we recruit," do you say, "Hallelujah, that levels the playing field," or you say, "You are inadvertently unintended consequence, you are hurting minority students"?

DiCo:

I can see it both ways, but I don't think college is the be-all, end-all necessarily, because I know lots of people without college degrees who are very successful and lots of people with college degrees who are not. I think what it comes down to is the quality of education that people are getting, especially in the foundational K through twelve years. And if they want to pursue vocational school afterwards or graduate school afterwards or college afterwards or whatever, professional school, they have options.

And I know lots of people that skipped college and took a coding bootcamp and are now making twice as much money as I am and good for them. But had they not gotten the foundations in K through twelve, they don't have options. When John talks about his life in his middle school when he moved here from Virginia, he couldn't believe that in the middle school in the Bronx where he was, nobody knew how to read.

And these are things that we take for granted that literacy, that's a right that people enjoy. And it's not right now. I think that's the wrong question to be focusing on of whether colleges are requiring SAT scores or CEOs are requiring college degrees. And I think we have to be looking way earlier down the pipeline of somebody's life of, what was your educational experience from K through twelve? Were you in a place where you were safe enough to focus on your school and prioritized and valued enough given the resources you needed to succeed?

John probably told you the reason that he came into my debate class at FDA during his lunch period was not because he was curious about philosophy. It's because he wasn't safe in the cafeteria because there were rival gang members there that could have hurt him. Kids can't focus on learning if they're worried about being safe.