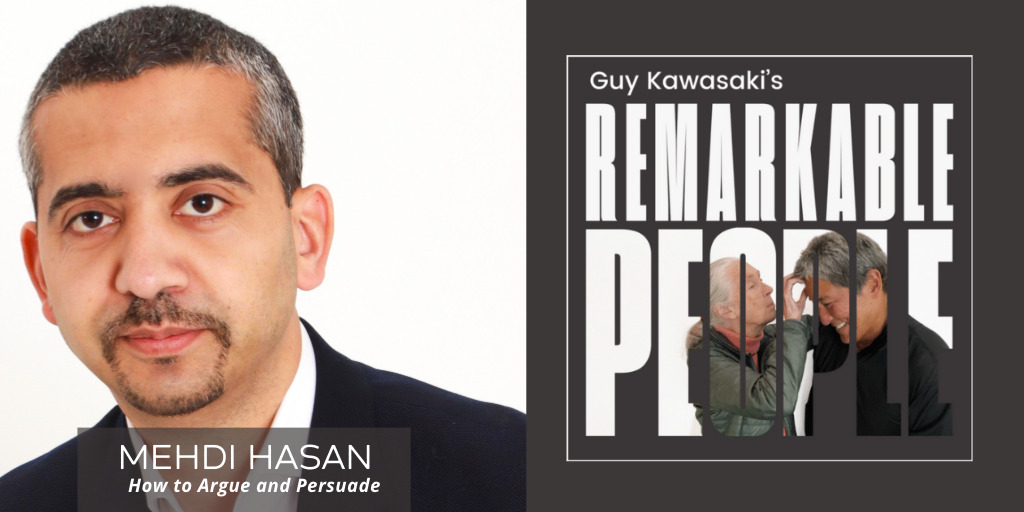

This is Remarkable People. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Mehdi Hasan, one of the most prominent and outspoken voices in politics, current events, and society.

Mehdi is a MSNBC commentator and host of The Mehdi Hasan Show on Peacock. Mehdi is also a best-selling author, and his new book, Win Every Argument: The Art of Debating, Persuading, and Public Speaking, shows readers how to win arguments and debates.

I learned a new concept in this interview. It’s called the gish gallop. The American people will be inundated with this technique for the next two years, so pay careful attention to what Mehdi says.

Please enjoy this remarkable episode with Mehdi Hasan: How to Argue and Persuade!

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Mehdi Hasan: How to Argue and Persuade:

Guy Kawasaki: I am Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. We're on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Mehdi Hasan, one of the most prominent and outspoken voices in politics, current events, and society. Mehdi is a commentator on MSNBC and is the host of the Mehdi Hasan Show on Peacock. He is also a bestselling author, and his new book, Win Every Argument: The Art of Debating, Persuading, and Public Speaking, shows readers how to win arguments and debates. I learned a new concept in this interview - it's called the Gish gallop. The American people will be inundated with this technique for the next two years, so pay careful attention to what Mehdi says.

I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People, and now, here is the remarkable Mehdi Hasan.

What is it like being a Muslim in Western countries today?

Medhi Hasan: That is a deep question. It's a question that I've asked myself, I've asked my kids, I talk to friends about it constantly. To be fair, less so than I did ten or fifteen years ago; I think things have improved but for all the wrong reasons, Guy, the reason why people aren't talking about Muslims in a threatening way anymore is because people have realized there are other bigger threats to us all - so we don't talk about Muslim terrorism anymore because we're so busy worried about domestic terrorism. And we're speaking, Guy, after a weekend in which there were two massacres of people, one on Saturday in Texas, a shooting, and one at the border in Texas where a guy drove his car and both, so far we don't know for sure, but have been linked to far right causes. So being a Muslim right now in the West, I grew up as a Muslim in the UK, Guy, until my thirties. I moved to the US nearly a decade ago. I've been living as a Muslim in the US.

My kids are British and American, they're dual national. It is hard because since 9/11 in particular, but also pre 9/11, there has always been the case that you have to somehow prove that you are not the angry Muslim ,regardless of your resting face. You have to prove that you're not the extremist and you have to fit this loaded box that says, "Don't worry about me, I'm a moderate Muslim," which is a very loaded phrase. What does it mean to be a moderate Muslim? So there's always a sense of difference. There's always a sense of having to prove yourself. There's always a sense of having to do things that others wouldn't have to do to be accepted, and the struggle continues. But as I say, things are much better than they were. I work at MSNBC now, I do primetime shows for them. Ten, fifteen, twenty years ago, I'd have laughed in your face if you said there'd been an opinionated, outspoken Muslim hosting on mainstream American TV. So things are improving for sure, and Muslims in Congress as you know.

Guy Kawasaki: So, still, have you had "the talk" with your kids about if they're pulled over or something?

Medhi Hasan: Not a pulled over conversation because I don't think Muslim women have to worry too much about that in the same way that young black men do, but I've definitely had the Muslim parent talk, which is be careful what you say about your religion in public. Be careful what you say about other religions. Be careful what you say politically. During the Trump era, one of my kids would tell me that, "Oh, people on the bus are talking about Donald Trump." And I would say, "You don't." Keep your head down because, of course, as Muslims, as young Muslims in an age where Muslims, immigrants, people of color are being targeted in a Trump era as outsiders, as threats, as not real Americans, that's not what I want my kids to have to put up with. Now, that's not what I'm going to tell them for their whole lives. At some point I do want them to speak out, but not as young children. No.

Guy Kawasaki: Okay, and pardon the ignorance and maybe blasphemy of this next question, but is Islam that different from Christianity? I think there's a lot of people in the United States who try to make out Islam as inherently violent and they're all trying to kill us and they all got bombs strapped underneath their trench coats. But fundamentally, is it that different?

Medhi Hasan: No is the answer. We, Muslims, consider themselves to be part of the Abrahamic faith tradition alongside Jews and Christians. In many ways, Islam and Judaism is more similar to each other than Judaism and Christianity. In many ways, Islam and Christianity are more similar to each other than Christianity and Judaism. So it's very strange in the sense that Islam could be paired up with either of those Abrahamic faiths and you could say they have more in common than with the third Abrahamic faith. So, I always find it odd when people try and yet treat the Judeo-Christian tradition and Muslims as some outsiders to that tradition. As for your point about violence, it's something I've been arguing for twenty years, the great myth of Islam as a uniquely violent, intolerant religion, but not just right wingers and Trump types of push... The Sam Harrises and Bill Mars of this world have pushed for years, "liberal centrists," the Richard Dawkins types, the new atheists.

And it's been a source of great frustration that the facts just don't get through on this. And that is right now, for example, the FBI says the biggest terrorist threat to the United States is a domestic far right terror threat. As I mentioned over the weekend, we have people killed possibly by far right types. So it's funny because I just did a segment on my show about this whole, "Republican refrain of thoughts and prayers" every time there's a mass shooting. Thoughts and prayers, but no action. And I ended up quoting from the Bible and the Quran, the same line, almost the same line, which is, "faith doesn't work unless you also have action." So the faith tradition, the messages, the background, the history, yes, it's all very similar. What the real issue, Guy, which people don't really want to admit, is that it's much less about religion, much less about theology, and it's to do with race.

The reason why Muslims stand out is not because of our theological views, it's because we're brown. It's because we don't look like what the archetypal white-American is supposed to look like. So a lot of this, as with most things in America, all roads lead back to race.

Guy Kawasaki: The myth that America is land of the free and equal and all that is pretty much bullshit at this point. We should just come to grips, we are a racist society.

Medhi Hasan: Oh, if you say that, Guy, you'll be accused of hating America. You'll be asked to leave the country. You'll be claiming that you're anti-American. What's really interesting, I don't know if you've noticed Guy, but right now there's Nikki Haley running for president on the Republican side, a brown woman, daughter of Indian immigrants, and Tim Scott of South Carolina, also from the same state, black man, is about to declare in the coming weeks to run for president. So you'll have two people of color running there. And there's another guy, Vivek Ramaswamy, I think his name is.

Guy Kawasaki: Yeah.

Medhi Hasan: Who's also running pointlessly. But it's interesting that all these black and brown Republicans, they make it very clear when they run, "We don't think America's a racist country." They go out of their way to say that because you need to make the white Republicans feel comfortable with you, but then they throw in the line when they do their backstory of how they overcame racism.

So Nikki Haley has a whole story about her family and her father getting stopped by police in her fruit cart, how she had a beauty contest, wasn't allowed to take part as a kid because she wasn't black or white. But they say all this stuff and then they say, "But you can't say America's a racist country." You can't say anything about systemic racism because that would take you to critical race theory and critical race theory is Marxist indoctrination that's destroying America.

So it's hard to have these conversations, sadly. But yes, you're right, the BS, it's very clear what is happening in America today. The guy, Donald Trump, who said he wants to ban Muslims and build a wall, was not just elected, but second time round even though he lost, he increased his vote share and now he's running for president again and Rolling Stone reported last week that he's told people in private, he wants to bring the Muslim ban back when he gets back into office.

Guy Kawasaki: I'm shaking my head, I'm shaking every part of my body actually. Can you foresee a time where Muslims are registered and interned just like Japanese were doing World War II? And in my mind, that's eminently possible.

Medhi Hasan: Oh, it is eminently possible. Anyone who tells you otherwise is a fool or a liar because as you point out, it's happened before in American history and Donald Trump in 2016, people forget, he ran saying he would consider a registry for Muslims. And when he was challenged and said, "How would this be different to what happened to Jews in Nazi Germany?" He said, "You tell me." This is what he said to the reporter. "You tell me," was his response at the time. And we know that a second Trump term would be a deeply lawless term. There would be no guardrails. There would be no adults in the room. And yes, Muslims are an easy target. As I say, right now, we're not so much on the radar because ISIS has been defeated, the terrorist attacks are not at the same level, thankfully that they were a decade ago, and because we all know the real terrorist threat are the people who tried to literally overturn an election and attack our capitol who were white Christian dudes.

So in that sense, we are not number one villain of the month right now. I think Muslims have to get behind Mexican immigrants and transgender athletes right now as the number one boogeyman in society. But look, it only takes, God forbid, a terrorist attack or something else to easily make Muslims again a target and allows people like Trump to fear monger about Muslims and minorities. And I still meet Muslim friends of mine who joke about, "I'll see you in the camps if Trump gets back in." And it's black humor that we engage in, dark humor, but it's eminently possible. Anyone who says otherwise doesn't understand or know the history of this country.

Guy, we're all in this together. I know it's a cliche, but I've been banging this drum for seven, eight years. There's no scenario in which you can allow people on the far right to play, divide, and rule with minorities, to do a whole, "These minorities are good. This is the model minority. These are the hardworking people, and these are the criminals and these are the terrorists, and these are the invaders," because once they come for one group, they come for all groups. And we've seen that. Look at the hate crimes against AAPI people. Look at the hate crimes against Jews. Look at the hate crimes against Muslims. Look at the hate crimes against black people. Look at the hate crimes against LGBTQ people. They're up across the board. There's no group that has been inoculated or immunized from hate crimes over the last few years. Just look at the FBI data.

Guy Kawasaki: Mehdi, you got to tell us how you really feel. Stop holding yourself back. Okay? Ah, I got a smile out of you.

Medhi Hasan: That's what my wife-

Guy Kawasaki: I got a smile out of you.

Medhi Hasan: ... says to me very often.

Guy Kawasaki: This is the resting happy Muslim face I saw. Okay, switching gears here. I really enjoyed your book. I enjoy books about psychology and Bob Cialdini and Angela Duckworth and Katie Milkman and Mehdi Hasan. But I have to ask you, in a sense, is life one long debate contest? Because it seems to me that your book is about winning arguments, but winning arguments may not be what life is. Is life winning arguments or influencing and persuading people to join you? Because the two things are different.

Medhi Hasan: Well, there's a lot of questions in that one question. I would say, first off, are they that different? I think we can get lost in pedantry. I think some of the skillset are the same, and I think some of the goals can be the same. Is life one big argument? Yes. Is life about winning arguments? No. The title of the book through a lot of people, a lot of people have said to me while I've been on book tour saying, "Do you really want to win every argument? Is it wise to want to win every argument?" And just to be clear, I'm not saying you should win every argument. Of course not. And I actually make it very clear at the start of the book, don't try it with your spouse. That's one place I definitely don't try and win arguments.

But what I am saying is, win every argument. I'm providing you with the skillset to win any argument you should choose to engage in. That's not the same thing as you should go out and just argue with everyone all the time. It's like if I wrote a book called Drive Every Car, I'm not saying go out and literally drive every car. I'm saying this gives you the skills to drive any car that you would like to drive.

So the point I've made, and I'll say it again is, sometimes you can't avoid arguments, Guy. Sometimes, and it depends how you define it. So I for example, define it very broadly. I would say, for example, if you go for a job interview to try and get a job, that is an argument. You're trying to win an argument, you're making an argument, hire me. Don't hire the guy you're going to interview after me or the guy you interviewed before me. And you may even know in your head that you're probably not the best guy for the job. So you're arguing something maybe you know is not true, that you're the best, but you need to do it because you need the money, you need to put food on the table, you need to pay for your kid's education. So you are making an argument for yourself in that context. And there's multiple contexts like that where we can't avoid the argument. We have to engage in the argument, and we have to win whether or not we think it's right or proper or correct.

So, I wrote this book for the world as it is, not as the world as we want it to be. I would love to live in a world which was free of bad faith arguments, in particular. But this book is about good faith arguments. I talk very much about the democratic moment that we're in, that I believe that democracy cannot be safeguarded, our free press cannot exist without open debate, without the willingness to argue for and against a point, without free and open discussion and disagreement. So, it's a tricky one. I'm very much not saying we should spend our whole lives arguing, but I am saying we cannot avoid argument and therefore we should be properly equipped for it and right now, we live in America in a world filled with bad faith actors pushing bad faith arguments at corroding and degrading our public squares, and we need to be equipped to push back.

Guy Kawasaki: So one of the methods that you cite as being most effective is showing the receipts. Now, I understand that concept completely, but if you follow news today, it's not clear to me that receipts matter. There's plenty of receipts about Clarence Thomas's trips and tuition payments and payments to the spouses of Supreme Court Justices, but those receipts don't seem to matter.

Medhi Hasan: So yes, we do live in an America where receipts have become increasingly harder to deploy and use. And when I talk about receipts, I'm talking about evidence, facts, figures, statistics, empirical evidence to back up your claims. And I think you cannot really ever fully win an argument unless you have that evidence. Now, what I cite in the book, I cite studies from the Political Behavior Journal and other places from Pew, Gallup, polling that shows, "Look, people still do value facts, figures, and evidence." You still can change some people's minds, but it's a smaller pool of people. It's an increasingly shrinking group of people who are willing to be open-minded, willing to hear out the evidence, willing to consider A, B, C, and make a decision because yes, a lot more Americans and previously are locked into their partisan tribes, are locked into their information bubbles, are cut off from facts and figures.

I would say anywhere up to maybe thirty percent of Americans now are just beyond facts and figures, are just not reachable by conventional methods of proof, debate, and argument. Now, that doesn't mean the rest of us should give up on it and one of the main points in my book is, sometimes we get lost in arguing with the other person, the person in front of us, and saying, "I'm not getting through to them. Okay, fine. Maybe you're not getting through to them, but are you getting through to a third person? Are you getting through to an audience that's watching?" And my big point is, "Yeah, there are tens of millions of Americans who aren't going to listen to me about Clarence Thomas, who aren't going to hear the evidence about the corruption at the heart of the Supreme Court, but there are tens of millions of other Americans who are, who need to see the receipts, who need to be equipped with the facts and figures so that they can debate with their family members, friends, colleagues, neighbors."

And I think that's what's so important. Sometimes we forget about the broader audience, the big picture, and we get locked into a pointless battle with someone who's never going to change their mind. And people keep saying to you, "How do you argue with someone who's got a closed mind?" Don't argue with them. Make your case to the wider public.

Guy Kawasaki: And what do we do with the thirty percent that will not listen to... Do you just write them off? What do you do?

Medhi Hasan: It is the $64 million question of our age. What do you do about an increasing number of Americans who have made it very clear? There's a poll out today, Guy, the day we're speaking for, I think it's from YouGov and it's going viral on social media. It's a trust-in-media poll and they polled Republicans and Democrats on which media sources they trust. Here's crazy stats, that Democrats are more likely to trust far right wing media outlets than Republicans are likely to trust C-SPAN. That's how much trust in media and public institutions has created on the right. The right basically trusts Fox, Breitbart, and that's about it. No one else. Democrats still trust a variety of sources including right wing sources.

So we live in this age where they've lost all trust with the media, they've been told the media is fake news, public institutions have been demonized to the point where, something I never thought would happen in our lifetime, Republican politicians are saying, "Defund the FBI, defund the FBI." Republican politicians are attacking the military and generals. There was a time when you would never imagine the Republican body would be anti-law enforcement and the military, anti the CIA. They're anti everyone. So they're anti all the public institutions. What do you do on that level? When we live in a social media age in particular, where lies go viral, where misinformation is rife? It's very hard to get through to some of these people who have that media diet. And I work for a news channel, I work for MSNBC, which people say, "Oh, you are just a left wing Fox," which is a nonsense, but clearly parties and people watch my channel, I'm an opinion journalist, but we're still news. We're still within the realm of reality. I still try and provide facts and figures for what I'm saying, unlike the Fox guys who as we saw in the Dominion trial, are saying one thing in public and one thing in private.

So when you live in that kind of information age where misinformation is rife and people are in their bubbles and partisanship is high, and you have cult leaders like Trump on the scene, yeah, I don't have an answer for what we do. I do know that if we continue down this path, democracy can't survive. Democracy can't survive if tens of millions of people in the country don't accept basic reality, don't accept the rules of the game, whereby when you lose, you concede defeat. You don't launch a violent insurrection. Yeah, I think you have to hope that young generations, that younger voters will save us, which is a big hope. We have to put a lot of faith in younger generations to be more political and media literate, to be more open-minded, and I think we have to reinforce our institutions as they are.

You mentioned the Supreme Court. A lot of our institutions are not fit for purpose and therefore the bad faith actors and the authoritarians and the cultus are able to exploit them. So I would like to see us democratize our institutions much more, reinforce our failing and broken political and democratic institutions. I would like to see young people energized, emboldened, empowered much more, and yeah, for the twenty-five percent of Republicans who think QAnon is real, I don't see how you get through to them. I think you've just got to contain them, in a sense, and try and prevent them from doing damage and try and prevent them from holding on to the levers of power.

Guy Kawasaki: A few months ago, I interviewed a guy named Mark Labberton, and at the time he was president of the Fuller Seminary, which is the Harvard Business School of Christianity, really. And I asked him about this question, what do you do about people who just don't believe and so contrary to you? And he said, "Rather than arguing with them about facts and figures and trying to change their mind, the question you should pose to them is how did you come to believe? How did you come to believe the election was stolen? How did you come to believe that vaccination doesn't work?" And by asking that question, it reduces the barrier and it fosters discourse that has a chance of changing people.

Medhi Hasan: So I would half agree and half disagree. I definitely think you need to get to the source of the problem, and for me, the media is everything. I always say, you show me an extremist, you show me a terrorist, you show me a conspiracy theorist, and I will show you their social media diet. I will show you what they've been reading and watching. People don't wake up one morning and believe in QAnon - that is taught to them, that is something that they imbibe through traveling down rabbit holes online. I consume so much of this stuff and I watch so much of what the right is producing, that when I see or hear people send me hate mail, troll me on Twitter, if I meet a family member who pushes some right wing... I know exactly where it's come from, I can trace the origins of that, and that's clear to me.

Having said that, there's polling and focus group work and reporting that shows there are people who will tell you that the election was stolen. And you will say to them, "What's your evidence?" They say, "We don't have any evidence." They're very open about, "We don't have evidence, but that's what we believe." The same people who say facts don't care about your feelings, their feelings are more important than facts. And so, I write in the book a chapter about feelings, not just facts about appealing to people's emotions. If you do want to reach some of these people, and some people you may not want to reach, you have to find some common ground. You have to be able to appeal to their hearts and not just their heads. Receipts are important, but emotions are even more important. I talk about the importance of storytelling. I talk about the importance of showing your own emotions to engage with people, to find some kind of engagement and connection.

And there's been a lot of work done that I don't address in the book. The deep canvassing, for example, the people have done, a lot of political scientists have done this work on, if you go and talk to someone who's anti-transgender at the doorstep and you spend ten minutes just letting them speak and hearing them out, the importance of listening, that can translate into a changed mind over the course of three to six months, it has an enduring effect. Now the problem with that is, it's not scalable. You can't go and knock on everyone's door in America and get through to them in the same way. Plus, after you've knocked on their door and made your case and found some common ground and great kumbaya, that person then goes back and watches Sean Hannity or Tucker Carlson, and it's all undone.

So again, the media diet is so crucial, but yes, there are certain things you can do, and I talk about it in the book. You can engage with people emotionally, which is better than engaging with them factually. You can engage with people by hearing them out, empathetic listening, by putting yourself in their shoes, making them clear that they're being heard, even if they're wrong, even if you don't agree with them, you're hearing them out. A lot of the people just want to be heard. So there are different methods. None of them are easy. There's no silver bullet here, Guy, sadly.

Guy Kawasaki: Okay, let's look at January sixth. So I'll give you two sides of what's happened about January 6th. There are a thousand people who were indicted and roughly 500 have been convicted or pleaded guilty. There has been no exonerations. So you look at that, you say the system works. The flip side is, roughly half of the Republicans think that January 6th was peaceful and it was legitimate political discourse.

Medhi Hasan: Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki: So what do you make of those two completely contradictory things?

Medhi Hasan: It tells me two things. Number one, facts on their own will not convince anyone. So you can bring all the statistics you want about how many people have been indicted and convicted; they will move the goalposts. Number two, it tells me that, again, media diet, the people who are saying it's legitimate political discourse, the people who are saying it was peaceful, the people who are saying these were just tourists. Where are they getting that from, Guy? They're getting it from Tucker Carlson who gets the footage from Kevin McCarthy when he used to have a Fox show, he no longer does, but he did it on his Fox show. He showed selective footage to say this was peaceful, to the point where even Republican senator said, "This is garbage. We don't accept what Tucker Carlson is saying. Our lives were in danger that day." So yes, the ability to take January the sixth and transform it, shows you the power of propaganda. And what's interesting Guy, is if you polled people in the days immediately after 1/6, they didn't hold these views. It takes time to create a propaganda narrative, to disseminate it to your base, and to have it imbibed and repeated as fact to one another. And that's a mistake that Democrats made by allowing all of these investigations and trials into Donald Trump, into the insurrectionists, to drag out for so long because we don't have time on our side when it comes to stopping these narratives from forming and hardening. Everything should have been done much more quickly.

I also think you mentioned if 500 convictions or guilty pleas, et cetera, none of the ringleaders, Guy, none of the ringleaders, these are all the foot soldiers. And that's another problem. Unless you hold the people at the top to account and tell the story fully in the way the 1/6 Committee partly did, you're not going to be able to change people's minds. But above all else, I say in the book, "Show, don't just tell." And I think the power of imagery is very important. Just telling people, 500 people arrested is not enough. You got to get them to watch the footage of police being assaulted, of police being hit with poles, of police being teargassed and electrocuted and say, "This is what you support? This is the peaceful protest?" I think you've got to bombard them with that imagery. Look at the way that Fox used imagery of burning cities. Much of it was months old, and they used it during the summer of 2020 on a loop. They were showing Portland burning night after night, three months after, they were showing it as if it had just happened tonight. And what does that do? That led to millions of Republicans today who believe that the summer of 2020 was a summer of violence and looting and rioting and burnt cities, which is actually not what the evidence shows, but that's what they saw night after night after night.

Guy Kawasaki: Okay, so in your book, you discuss ethos, pathos, and logos, character, emotions and logic as the three factors for winning arguments and discussions. And so I look at those three factors, character, emotions and logic, and I say to myself, how the hell does Donald Trump get seventy-five million people to vote for him if you apply those three factors? His ethos, his pathos, his logos, what am I missing?

Medhi Hasan: So what you're missing is that we define these things in ways that fit with our rational, liberal, conventional mindsets. Just for your viewers and listeners, those three appeals: the emotional appeal, the logical appeal, the character based appeal, pathos, logos, ethos, they go back to Aristotle. This is 2000 years old stuff, this has been talked about and agreed upon. Let's just take one of them, Guy, ethos, your personal credibility, your character, your ability to persuade people based on who you are and what you've done. Donald Trump has ethos. It may not be the ethos you and I respect or agree with, but let's not forget when he runs in 2016, he runs almost purely on ethos at the front. He has a lot of pathos as well. He knows how to emotionally rouse his base with demagogic rhetoric. He doesn't really do logos. I think we can all agree, but ethos, oh yeah, that's a big part of his appeal in 2016.

I'm the businessman. I'm the guy you saw on The Apprentice firing people. I'm the multimillionaire realtor. I'm the guy who gets stuff done, and I'm the guy who's going to go and knock some heads together in Washington DC. I am the outsider. I'm the guy you send to burn it all down. Trust me, you know me. You've seen me on TV do it. There is no presidency of Donald J. Trump without The Apprentice. The Apprentice is what cements him in the popular imagination in the public mind as this can-do, brilliant, billionaire businessman, complete opposite of reality. The reality is he's a failed businessman, multiple bankruptcy, lied about his wealth, can't even fire the people around him, he's such a coward, but created a fake game show where he fires people on TV. So yes, I would argue that his own weird, distorted version of character and credibility, his own ethos, definitely had an appeal to millions of Americans.

Guy Kawasaki: Wow. Let's say the Democrats call you and say, "Man, we need some advice. Are Democrats just basically too wimpy?"

Medhi Hasan: Yes, sure answer, yes.

Guy Kawasaki: What would you do?

Medhi Hasan: You got to replace a lot of the people at the top of the party who just don't have the stomach for this fight. Let me give you one example, something you and I have been nodding towards for all of our conversation. Clarence Thomas right now is thumbing his nose at the American people and at the political establishment saying, "What are you going to do about it?" Every day there's a new revelation. This billionaire paid for his great nephew who he brought up, paid for his private school education, paid for Clarence Thomas to go on jets and yachts, paid for his mother's house, paid for part of his wife's salary indirectly, other billionaires have paid for Ginny Thomas's salary. Just every day a new revelation, just one of them would be enough to sink a Supreme Court justice, multiple. And yet he's untouchable. Why is he untouchable? Not because Democrats don't have power, but because Democrats refuse to wield power and because Democrats refuse to go on the offensive.

Dick Durbin is the chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee. Here's what he said about trying to get Dianne Feinstein, who's another democratic senator who's absent right now because of illness - when he tried to get her off the committee so he could bring in another Democrat and have the number of votes he needed, he said, "I would like the Republicans to show kindness." Kindness? Have you been asleep for ten years? What are you talking about? Because they're not going to show you kindness. This is zero sum politics, scorched earth. On the weekend he said, "History will judge Clarence Thomas." Now history won't judge him. You are supposed to judge him. You are supposed to hold him to account. The rhetoric, the action. It is weak. It is timid. They bring a butter knife to a gunfight. Republicans bring a rocket launcher.

And that's just in terms of actions, Guy, don't even get me started on rhetoric. I talk in the book about how Democrats will always want to win a debate, win an argument, win over voters with facts and figures. That's not how it works. The Democrats are the people, Guy, who say, "If you give me just a few more minutes to give you a few more statistics, one more pupil, one more peer reviewed paper and I'll win you over." That's not how human beings get convinced. Republicans come along, Donald Trump comes along and says, "Build a wall. Ban Muslims. Lock her up." He said that in 2016, Guy, we all still remember it because it was pithy, it was emotive, it was rousing. It was horrible in many ways, but it was memorable. What did Hillary Clinton say? I'll give you my seventeen-point childcare plan, which I'm sure was a great childcare plan, but that is not how you engage with people. That is not memorable messaging.

The Democrat messaging needs to be more aggressive. It needs to be more emotive. It needs to meet people where they are not where you want them to be. It needs to be something that rouses your own base. There's much they could be doing that they're not doing. I'm glad Joe Biden put out a video announcing his reelection in which he hit the Republicans on 1/6, on the insurrection, on book banning, on freedom. That's more of what I would like to see. Gavin Newsom, the governor of California, has been very aggressive in trying to reclaim the language of freedom from the right. I highly approve of that. These values, freedom, equality, liberty, you have to reclaim them.

Guy Kawasaki: So one of the concepts you discuss in the book is a Gish gallop. Is it Gish, Gish, or Gish?

Medhi Hasan: Gish. The Gish gallop.

Guy Kawasaki: I had never heard of the concept. So first, just for my listeners, can you explain the concept?

Speaker 2: So the Gish gallop is the technique that's known in debate circles and that's used by people like Donald Trump or a Marjorie Taylor Green today. It's become much more common today, sadly, in politics, which is whereby the debater, the speaker, the person you're arguing with, tries to overwhelm you with, for want of a better word, bullshit. Wants to just steamroll you with cherry picked facts, out of context quotes, distorted studies, and wants to throw them at you at a pace and with relentlessness so that you are unable to rebut all of them or even any of them because there's so many of them, and we see that with Donald Trump. He throws you nineteen lies in one statement. You're trying to rebut lie number seven, he's onto lie number twelve, you get to lie number twelve, he's already onto line number twenty-five. So it makes it very hard for somebody to defend against that; it's one of the trickiest techniques to argue back against.

It's why it's so cynically effective, ,t's why Trump does it, because you don't have to engage in facts and figures. You don't need substance. You just throw enough shit against the wall, see what sticks, and see your opponent basically get drowned in the bullshit. And the name comes from a guy called Duane Gish, who was a Christian creationist who would debate evolution in the nineties and the eighties with evolutionary biologists. And you would think this guy is a creationist. He's not a scientist. He'll lose. He'll lose to the scientist, but he would win. And he would win because the scientist was not trained in the art of debate, would come along and start quoting lengthy scientific papers, and Gish would throw a hundred questions and a hundred rebuttals at him, most of them nonsense, but the scientists couldn't respond to them all and the audience would say, "Wow, this Duane Gish really knows his stuff." And Trump has whether knowingly, unknowingly borrowed this technique as have many Republicans now, many Trump mini-me's.

Guy Kawasaki: Okay. So if you're on the opposite side of this, what are you supposed to do?

Medhi Hasan: So, it's very hard to push back against. I in the book, give three techniques that I think you can use and I've used and others have used to try and push back against a Gish galloper. Number one, I say pick your battle. Somebody throws seventeen lies at you, don't try and respond to all seventeen because that's what they want you to do. They want you to spread yourself thin and you'll look foolish and you'll run out of time. Pick one. Pick the weakest, most ridiculous thing that your opponent said, focus in on that, and make the audience believe that yeah, the rest of the stuff they said was also bullshit.

So I give an example in the book when I was debating a woman on Islam at the Oxford Union many years ago, an Islamophobe, she basically did a long rant where she accused Muslims of 200 different crimes and I wasn't going to be able to respond to all of them in my time. So I just picked on one thing she said, which was that, "Saudi Arabia is the birthplace of Islam." And I said, "Saudi Arabia was formed in 1932. Islam was created in 622. You're only thousands of years off." Got a big laugh from the audience, damaged her credibility, her ethos, from the get-go and I didn't need to deal with all the other points. It made it very clear to the audience, "Don't trust her. Her claims are nonsensical." So first thing is pick your battle.

Number two is don't budge. The Gish galloper Trump wants you to move on to the next question. And I once interviewed a Trump proxy, a guy called Steve Rogers, sadly not Captain America, and he basically came to the interview and tried to defend Trump and I said to him, "Donald Trump said that six new steel mills have been created since because of his policies. US Steel have said that there are not six new steel mills." And he said, "What he meant to say was, there's a lot more steel being produced." I said, "That's not what he said though. He said, 'six new steel mills.''" "That's not what he meant. Manufacturing's up, Trump's doing well." "Great, deal with my point. Six new steel mills." I wouldn't budge and I kept asking him the same question, and at one point, he got so frustrated and so flustered; he was so unused to this because he's used to interviewers moving on to the next subject. He said, "Just ask me your next question." And I said, "No, I'm not going to ask you the next question. That's what you want me to do. I want you to answer this question." So don't budge. The Gish galloper relies on you moving on. Don't move on.

And number three, call it out. Make it clear to the audience what's going on. Tell the audience this person is engaged in nonsense, "Is trying to flood the zone with shit," to quote Steve Bannon. That Vladimir Putin does it too. And we need to point out when Vladimir Putin talks nonsense, we say, look, he's talking about Ukraine, but suddenly he's talking about transgender rights in the West. He's all over the place. Point out to the audience what's going on. There's a line, "Put raincoats on your audience to protect them from the fire hose of falsehood," is the analogy that the RAND Corporation gives. So number one, pick your battle. Number two, don't budge. Number three, call out what's going on.

Guy Kawasaki: Wow. So you could just focus on Jewish lasers and just never give that up. Just keep saying Jewish lasers, Jewish lasers, Jewish lasers.

Medhi Hasan: Yeah. She came on sixty minutes and the interview was deeply inadequate from Leslie Stahl, who's a storied, respected award-winning journalist, but that was a classic example where if you watch that interview with Marjorie Taylor Greene, Leslie Stahl tries to factor on a couple of things and immediately Greene takes over, starts Gish galloping being saying, "But what about my childhood? Are you going to ask me about my childhood? What about my speeding tickets? Are you going to ask me about speeding?" Don't get Gish galloped. Stahl should have said, "That's all fine. Answer my question about X."

Guy Kawasaki: And is there such a thing as a truth gallop?

Medhi Hasan: That's a great question, and I've not thought about that and I think there is such a thing as a truth gallop, and you know what I would call a truth gallop? I do a segment on my show called the Sixty Second Rant, where I speak very fast, like an auctioneer, as you could have guessed, I speak fast, but I speak even faster. And in sixty seconds, I try and cram as many facts on a topic as I can. So for example, Donald Trump says, "I've never said X, Y, Z." Sixty seconds, here's all the times he said it. So yeah, we call it the Sixty Second Rant on my show, but we could rebrand it as the truth gallop.

Guy Kawasaki: Feel free.

Medhi Hasan: That's a good name.

Guy Kawasaki: I made the resting angry Muslim face smile twice already. I like, hold a record for this. One of the points you make is that, in order to win arguments, you have to listen well. And so, how does one listen well?

Medhi Hasan: It's a great question and I'm not a very good listener. So when I wrote the chapter, I wrote it very honestly as someone who struggled with the issue myself, I say in the book, when I told my wife I was writing a chapter about listening, she laughed out loud and then she paused and she said, "You're writing a book about listening? You're an awful listener." I said, "I know. That's why I need to write this chapter because it's as much for me as for my readers."

Look, you have to be able to listen critically because you cannot win an argument if you're not paying attention to what your opponent is saying, if you're not on the lookout for lies, inaccuracies, contradictions, that requires critical listening. Engaging in what's being said. You also need to be an empathetic listener if you're arguing in public because you really want to have the audience on your side and to be an empathetic listener, as I mentioned a moment ago, you really need to put yourself in the other person's shoes, especially an audience member, even if you don't agree with them, you want them to feel heard, respected. You want them to feel like they have a dignity and a voice, and that's more likely to get them on your side, even if you don't agree maybe on one set of facts or political opinions. So empathetic listening is crucial, critical listening is crucial. For critical listening, I lay out several techniques in the book.

One key one that people don't really value anymore is note-taking. I think you've got to write stuff down. People don't really value this enough and I talk about how some of our great entrepreneurs and billionaires, the Bill Gates and Richard Branson's as well, they swear by old-fashioned note taking with a pen and paper, not on your phone, not on a laptop, with a pen and paper. And in fact, the example I gave a moment ago of pushing back against the Gish galloper in that Islam debate, who said "Saudi Arabia is the birthplace of Islam." I remember writing that down, Guy, and saying, 1932, and making a note, "I'm going to come back to this, I'm going to rebut this." So note taking's very important as a way of listening, getting off your phone is very important, great distraction. But in terms of empathetic listening, something again, we take for granted, but we don't do, eye contact, Guy, eye contact. I'm listening to you. Don't be looking at your phone. Don't be checking your watch as George Bush Senior famously did in a 1992 town hall where an audience member was asking him a question, he's busy looking at his watch, he's not paying attention.

Eye contact is so key to show someone that they are being heard, that you respect them, that you are trying to put yourself in their shoes. So I think there's many different ways to improve your listening skills. Obviously practice, it's not something you're just going to develop overnight, but I think critical listening requires things like emptying your mind of junk, not being distracted by your phone, maybe being able to take notes. And empathetic listening is about, for example, eye contact, showing that you are fully present, showing that you're paying attention, and that you're not just ignoring the other person.

Guy Kawasaki: I'm going to give you two pieces of data. First, I have a pen in my hand during this whole interview and I'm taking notes. And number two, I hope you noticed that I'm making a lot of eye contact. I have a trick and the trick is that this screen is being projected to an iPad, which reverses it, turns it upside down to a teleprompter so I can look right into your eye and still see this window, which is in a virtual setting, the way I can make eye contact, it's very hard to look at the camera screen.

Medhi Hasan: In virtual settings it's much harder. This is why in-person is always seen as a way to have the best interviews and have the best conversations. Even in this setting, I'm looking at my camera at the top of the screen. I'm trying not to look at the rest of the distractions on my screen or around me.

Guy Kawasaki: Yeah, I can send you the setup for a teleprompter to make it much easier if you want. Oh, third smile. Okay, so now I want practical tips about how to come up with zingers.

Medhi Hasan: I have a chapter in the book on the art of the zinger, and this is very important as we know from the social media age, with the mic drop emoji. You want to have that one line, ideally ten, fifteen seconds, something that's not too long, something that you may have work-shopped a bit or ideally spontaneous, but it can be work-shopped. And I mentioned in the book, Guy, the one most famous zingers from presidential debates were ones that were premade-

Guy Kawasaki: Elizabeth Warren.

Medhi Hasan: ...pre-fabricated. Elizabeth Warren's one minute takedown of Michael Bloomberg at the Presidential debates in 2020. Or the very short and sweet Lloyd Benson takedown of Dan Quail in the 1988 Vice Presidential debate where he says, "I knew Jack Kennedy. You're no Jack Kennedy." That came, as I point out in the book, from extensive debate prep where his team reminded him that this is a good line to use if Quail brings up the Kennedy analogy. So it wasn't some spontaneous thing that he pulled out of his backside. I'm someone who says, "Do your practice." If you could come up with one on the spot, great. If you're that nimble on your feet and you have that great a sense of humor, go for it. But if not, try and work out, "What is that one line? What is that one insult, mic drop, joke, gag, either self-deprecating or on the other opponent that you can have up your sleeve, that can get you out of a corner, that can give you the upper hand when you are backs against the wall?" And I cite a famous few from the presidential debates in the book.

In terms of practical terms, like I said, practice. But here's one other thing. Look at what people before you have said. And I talk about, it comes back to note taking. When you hear people use good lines, make a note. That's not because I want you to plagiarize them, it's because it's the kind of things that can inspire you. It's the thing you can synthesize with other great lines, and also, you can quote other people. There's nothing wrong with quoting people. I talk a lot about the importance of quoting in the book, using a quotation in a speech or in an argument or in a debate or in a column or in an article, it's very powerful because it gives you a sense of authority. It brings in a second voice to reiterate what you're saying, it provides a change of pace.

If it's a funny person, people say to me, "How important is an audience?" And I say, Billy Wilder, the movie director, and I quote him in the book, says, "One person, listening to one person, that person might be an imbecile, but a thousand imbeciles together in the dark, that's critical genius." That's the famous Billy Wilder. Always gets a smile or a laugh. Yet, that's a good way of making your point. So don't be afraid of quoting people. Don't be afraid of doing research and having some work-shopped lines up and make sure it's short and pithy and try it out on friends and family. I always say this, "Any kind of humor that you want to use in public, any kind of one-liner, test it out on people." Say, ""Hey, I'm going to say this. What do you think? Because they might say, "No, don't say that." And they may save you from some public humiliation. So what you think is funny, might not be what a room full of strangers think is funny.

Guy Kawasaki: Okay, so let me test out an idea I had for E. Jean Carroll.

Medhi Hasan: Okay.

Guy Kawasaki: So when Donald Trump, or they say, Donald Trump said, "I didn't rape her, she's not my type." I think E. Jean Carroll should have said, "Donald Trump's not my type. That's why it was rape."

Medhi Hasan: That's true. So just turn the line around. There you go. So that's another example of where you're using an existing line and making some changes to it and turning it back against your opponent. Something I often do in interviews. Something I do in interviews-

Guy Kawasaki: I love it.

Medhi Hasan: ... when I'm interviewing a guest is I will notice a verbal tick they may have. They may say a line again and again, and I'll wait for a moment, and I'll say that line back to them, and it totally disarms them.

Guy Kawasaki: I must say, preparing for this interview, I had reservations that I was going to get slaughtered.

Medhi Hasan: Never, Guy, never. Only when you come on my show, then I'll slaughter. No, I'm joking.

Guy Kawasaki: So you talk about zingers. Now I want to get two more really tactical pieces of information from you. One, how to make a grand entry, and two, how to make a grand exit.

Medhi Hasan: I have many examples in the book. Let me give you one on each. Grand entry. You want to start with something that's going to blow the crowd away in a few seconds. I say in the book that human beings, according to some studies, have a shorter attention span than a goldfish, like eight seconds. We have our phones, we scroll, you have an audience of people who are not a captive audience. There's no such thing as a captive audience anymore. You can switch the channel if you're at home. If you're live in an auditorium or a chamber, you can just go on your phone and ignore the speaker. So you have to grab them straight away. So what are you going to grab them with? You grab them with a question, a provocative question. You grab them with a provocative quote. You grab them with a provocative story. You want your opening line, as the Dale Carnegie quote, "The first thing you say is the most important thing." F-I-R-S-T, the first, not the second, not the third. People start speeches with, "Thank you for inviting me. It's great to be here." No, you're wasting precious time. Get straight into it. That's the grand entry.

Grand exit. You really want to go with a call-to-arms. You really want to leave people, A, leave them wanting more, there's that famous line. There's a quote I use in the book, which is, "People may not remember what you told them, but they'll remember how you made them feel." That's how you want to leave them, on a high. You want to leave them roused, inspired, uplifted.

So again, is it a story? Is it a quote, or is it a call-to-arms? I prefer to use a call-to-arms. I prefer to say at the end, "What are you going to do about it when you leave this room today, or when you finish watching this show? What should we do tonight? How do we stop racism? How do we end corruption on the Supreme Court? What are you going to do about it?"

Guy Kawasaki: What is a good press secretary supposed to do?

Medhi Hasan: That's a good question. I think if you are the president of the United States and you have a press secretary, you probably want them to do three things. You probably want them to be able to convey your message to the media in an eloquent, articulate, and competent manner, you probably want them to be able to spot crises before they've happened, see around corners, and you want them to be able to firefight once you're in the middle of a crisis, be able to get you out of the crisis, be able to have the connections and contacts and messaging and strategic abilities to get you out of trouble. Those are three things off the top of my head that I would want from a press secretary if I was a politician.

Guy Kawasaki: And obviously you must consider Jen Psaki one, but do you have, "these are press secretaries I really respect list?"

Medhi Hasan: Jen Psaki was very effective. I'm biased now because she's now a friend of mine since she's left office and she works at MSNBC with me. But I think it's fair to say most people thought she was very eloquent and dealt with some of the Fox folks in a very clever way in the Briefing Room. She clearly was across her brief. I don't know, it's a good question. I think a lot of press secretaries think that the best way to be is to bully the press, especially on the right. If you look at Ron DeSantis's team, who I've clashed with a lot on social media, they're just a bunch of online trolls and bullies who think that they can just scorched earth on journalists and treat the media as enemies. And I think that's now backfiring on DeSantis. He's now trying to run for president nationally. Turns out, you actually can't just demonize the media and expect to get good media coverage. Shock horror. Doesn't really work out for you on the national stage. It might work for you in little old Florida. It doesn't work for you on the national stage.

So I think a lot of these press secretaries really need to find the right balance between being tough and aggressive and actually being charming and being able to engage and win over journalists. I think the bigger challenge for those of us who are interviewers and journalists is not to get lost. My big worry is a lot of my colleagues get seduced by people in power. A lot of journalists in America, Britain, and beyond get too close to people in power and that's what I try and warn against, and I try and check myself from falling into that trap too.

Guy Kawasaki: And if you're a press secretary, who's your audience? The president, your boss, or the journalists, or the public?

Medhi Hasan: If you were Donald Trump's press secretary, certainly you were playing to an audience of one, which was you bash the media and hope the boss is watching and says, "You did a great job of defending me blindly." But no, that would be madness. If the only audience was your boss, your boss may not have the wisest or most best strategic sense. Your audience should be a mixture of the American public and the American media. Of course, you're sending different messages, to the public you're trying to show that you're across everything, you're on top of your game. Crisis. What crisis? Everything's fine.

And to the media, you're trying to project confidence. And I have a whole chapter in the book on the importance of confidence. If you don't look confident, people will not trust you. People will not believe you. People will not respect you. People will not hear you out. So you either have to be confident, or if you genuinely lack confidence in the moment, you have to fake it. You have to project confidence.

Guy Kawasaki: You had a few pages where you actually supported fake it till you make it right?

Medhi Hasan: Yeah and there's a reason for that. A, because it's effective. B, because we all have moments where we lack it, and C, because there's a lot of social science research, and I mentioned Amy Cuddy of Harvard who says that faking it till you make it actually is a self-fulfilling prophecy. Because when you fake it, you actually do become more confident so then you're not faking it.

Guy Kawasaki: As I was reading your book, I thought, "Man, it's inconceivable to me that the people who need your book the most are actually going to read it and believe it.

Medhi Hasan: That's a good point. And some people have very flatteringly said, "Oh, great book, but don't be silly. We can't be like you. Just reading this book won't turn us into you." And I say, "Number one, thank you very much. That's very kind, good for my ego. Number two, I'm not trying to make people like me. I'm not saying you read the book and you become a TV news anchor or you become Barack Obama public speaker. What I am saying is that you can improve your own skills and become a better speaker."

I'm very much of the school that people are not born speakers, there's no natural born orators. You can learn this stuff. Aristotle told us this 2000 years ago, Demosthenes, another famous ancient oratory I talk about, he began life as a very incompetent speaker with a very bad stutter, lacking in confidence, shortness of breath. He overcame it all and became the father of modern rhetoric, became the badass of rhetoric.

So it can be taught, it can be learned, it can be developed, and that's why I wrote the book. I would not have written the book if I didn't genuinely 100% believe that this stuff can be learned if you put your heart and soul into it, if you practice, if you read the right things, if you learn the right techniques. Now, does that mean overnight you're going to become Winston Churchill? No. But again, Winston Churchill didn't become Winston Churchill overnight. He spent decades practicing in the bathtub how to address the House of Commons, as I point out in the book.

Guy Kawasaki: As you mentioned in the House of Commons, there was a place where he just lost his train of thought.

Medhi Hasan: In his twenties when he was a young MP, before he was the famous Churchill of "fight them on the beaches" that we know today, he tries speaking impromptu without notes, and he crashes and burns. He loses his train of thought and he gets heckled from the podium.

Guy Kawasaki: This is a real tactical question, but you cite so many great stories of Aristotle, Socrates, et cetera, et cetera. How do you get these stories? It's not like you can just go to ChatGPT and get everything. Where do you get these stories?

Medhi Hasan: So I'm glad you appreciate the stories. A lot of people have appreciated the stories, and I have appreciated the stories because I didn't want to be a hypocrite. I didn't want to say, "You know what? The art of persuading people is through storytelling and then have no stories in the book." And nor did I want all the stories to be about me, because I'm not a complete megalomaniac. Even though your publisher and your agent says, "Make it personal, and people love personal anecdotes," and they do. So there's a mix of stories from my life and my career and interviews that I've done and experiences I've had, for example, in wintry rural southwest England. But see, I took a lot of news, I put it back to you, and there's stories from ancient history.

And the reason I tell stories from ancient history, A, they're fun like the Winston Churchill's story in the tab or in the House of Commons. But B, I want to show people, look, these great people, Martin Luther King, Winston Churchill, Demosthenes, these people had to work at what they did to become who they are. So you can too. I wanted to try and inspire the reader with role model stories. Now, I have a chapter in the book on research, the importance of research. I devoted an entire chapter to it. I'm someone who's always been known for doing a lot of research, bringing receipts. My interviews are known for being interviews where the guest says, "I never said that." And I say, "Yes, you did. In 1997, May the second at this venue, with this person you said, and I quote." And that's what we're known for, my team, both at Al Jazeera English, where I used to work, and now at MSNBC where I currently work, we work very hard to bring receipts, to do research, to do our homework, to dig deep beyond page one of Google, to read original sources and make sure that we are fully equipped with the right quotes and stories. And I applied that same technique to the book.

It was a lot of fun writing this book because A, it's a book I feel strongly about. B, it's a very personal book. And C, I enjoyed digging out these stories, some of which I already knew over the course of a lifetime of speaking about public speaking and rhetoric. And B, just in the course of the researching the book over the course of a year saying, "Hold on, let's work out how Winston Churchill became Winston Churchill." And then you're going to go and you get, I've got it. Where is it? If I've got it to hand, I can just pull it out for you. Do I have it to hand right here in a pile of nonsense I have by my desk? Let's have a look. Do I have it here? I want to have it here and throw it out. Sod's Law. I can't-

Guy Kawasaki: Take a screenshot, Madisun.

Medhi Hasan: So I've got... I'm looking around to show, look, this the kind of crap that I have on my... No, I'm going to find it. I'm going to find it. Here you go. Look, right here. Underneath my desk on the floor. Here is Boris Johnson, former Prime Minister of the UK writes the book, The Churchill Factor. Great book. As much as I loathe Boris Johnson as a politician and a prime minister, great writer, and this is the book where I came across the story about Churchill crashing and burning in the Parliament. It was a lot of fun, actually, Guy, to go, "Well, hold on. How did Aristotle become Aristotle? How did Demosthenes become Demosthenes? How did Elizabeth Warren destroy Michael Bloomberg?" And I went and I spoke to the Warren team, and I said, "Can I talk to you about this? How did you come up with this stuff?" And they told me the backstory. So yeah, we did the homework. I did the homework on this book just as I do on my show, and I'm glad it's come across, and I'm glad, someone like you appreciated it.

Guy Kawasaki: And if you were writing this book today, don't you think that ChatGPT would make it infinitely easier?

Medhi Hasan: It's a great question. We had a debate about ChatGPT on my show recently with two tech guys, one saying it's a threat to the democracy in our future and the other saying, it's amazing. I don't know where I stand on ChatGPT, I need to dig a little bit more. I did the debate on my show and I felt like I need to dig a bit more. When I first came across ChatGPT, I was blown away by it. Since then, I've seen a lot more critiques come out. For example, its factual accuracy has been questioned by a lot of people. It produces a lot of "biographical data" about people that's just not true. And it's susceptible to the same kind of political and racial biases that search engines and algorithms that we know are susceptible to. So clearly, it's a help.

Will it lead to a generation of high school and college students doing plagiarism? Maybe. That's what Google did at the beginning. Can it help shortcut some of your research? Sure. If that's the case, go for it. I have a chapter on research in the book. I would probably mention ChatGPT now, just as I talk about, in the book I talk about Google, for example, the ability to use Google to find what you need. I tell a story about how, one of the most famous interviews I've ever done with Eric Prince, the mercenary, the former founder of Blackwater, the brother of Betsy DeVos, it's one of the most famous interviews I've ever done. And one of the moments when I nail him is when I say, "You're working in Xinjiang, where Uyghurs are being genocided, how are you okay with that?" He says, "We're not working in Xinjiang. My company's not in Xinjiang." I said, "But your press release says you are." And he says, "No, no, no, that's in Chinese, that's a mistranslation." I said, "No, we found it in English on your company website. It's not translated."

It's a great moment in front of a live audience. And we found it that day, an hour before the interview, my producer found it literally by Googling the name of his company, Xinjiang, and PDF. And that's what came up.

Guy Kawasaki: ChatGPT is maybe the most valuable tool I have as a writer.

Medhi Hasan: Interesting.

Guy Kawasaki: And now-

Medhi Hasan: It's interesting to hear you say that.

Guy Kawasaki: Yeah. I'll give you an example. So in my book, Remarkable Mindset, I talk about how many remarkable people have made really diverse, major career changes. And so everybody uses the same old example, Jeff Bezos, investment banker, bookseller, that kind of example. And so I asked ChatGPT, "Give me examples of famous people who made big career changes." And it came up with Julia Child. Julia Child, until her mid-thirties was a spook. Then she married somebody in the CIA, they moved to France, she became interested in French cuisine. I would've never found that example without ChatGPT. Now, I have MadisunGPT, check ChatGPT, making sure that's not a bullshit story, but ChatGPT has changed my life as a writer. So anyway, I'm done. I hope I have broken the record for making Mehdi Hasan smile in an interview.

Medhi Hasan: Yes. Yes, I think you have.

Guy Kawasaki: Now my life is complete.

Medhi Hasan: Now your viewers and listeners have to go away and watch my interview on YouTube to actually see my resting angry Muslim face.

Guy Kawasaki: We'll use your angry face for promoting the episode.

Medhi Hasan: The reason I mention that in the book, the serious point of your listeners is, is your facial expressions matter, your body language matters. It's one of the crucial ways of winning over people.

Guy Kawasaki: You won me over. So-

Medhi Hasan: I appreciate that, Guy-

Guy Kawasaki: ... thank you so much.

Medhi Hasan: Thank you so much. It's been a great conversation.

Guy Kawasaki: I hope you enjoyed today's episode with a wealth of experience in political journalism and an unwavering commitment to the truth. Mehdi Hasan is one of the most respected voices in the industry today. I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People. Speaking of respected voices, there's Peg Fitzpatrick, Jeff Sieh, Shannon Hernandez, Alexis Nishimura, Luis Magana, and the most respected drop-in queen of Santa Cruz surfing, Madisun Nuismer. Until next time, Mahalo and Aloha!

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply