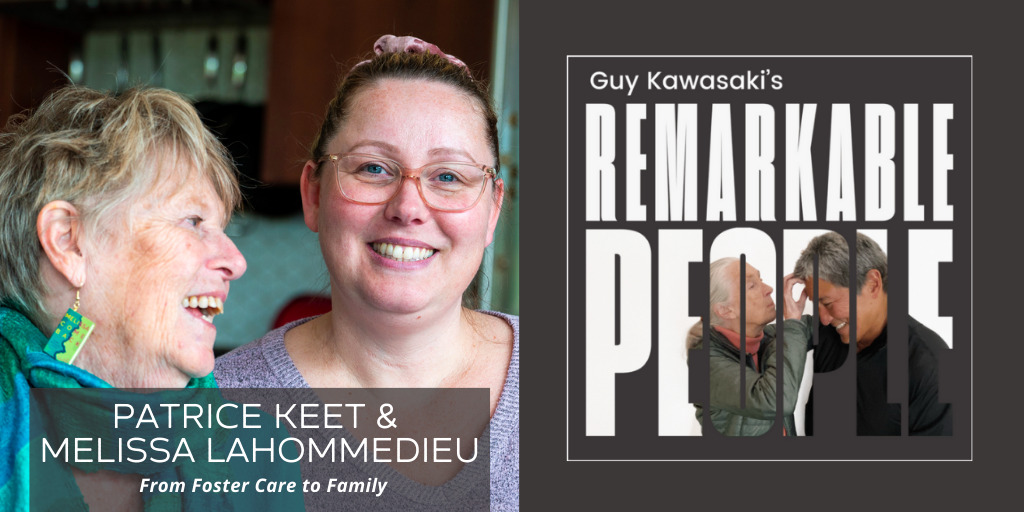

Welcome to Remarkable People. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Patrice Keet & Melissa LaHommedieu.

Patrice, a seasoned marriage and family therapist, and Melissa, a dedicated social worker, have a story that is nothing short of remarkable. Their lives intersected in a unique way, leading to a connection that has endured for decades. Their book, Melissa Come Back, captures the inextricably intertwined narratives of their lives, stemming from a unique connection. Melissa, once a foster child who ran away from Patrice’s home, reconnected with the Keets decades later.

In this episode, we delve into their experiences, the challenges they’ve faced, and the profound lessons they’ve learned. Patrice and Melissa’s insights are not just heartwarming but also profoundly thought-provoking, offering a fresh perspective on the power of human connections.

Whether you’re a fan of heartwarming stories, interested in the fields of therapy and social work, or simply seeking inspiration, this episode is for you. It’s a reminder that remarkable stories are all around us, waiting to be uncovered.

Join us on this journey of discovery and inspiration as we explore the remarkable lives of Patrice Keet & Melissa LaHommedieu. authors of Melissa Come Back. You won’t want to miss it!

If you are interested in learning more about their story and reading their book, check out www.melissacomeback.com

Please enjoy this remarkable episode Patrice Keet & Melissa LaHommedieu: From Foster Care to Family

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Patrice Keet & Melissa LaHommedieu: From Foster Care to Family

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. We're on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Patrice Keet and Melissa LaHommedieu. Together they are the authors of a book called Melissa Come Back. It captures the extraordinary story of their relationship.

Melissa was a foster child who ran away from Patrice's home. Decades later, they reconnected by pure chance. Their narratives, like their lives, have been intertwined ever since. Patrice is a marriage and family therapist, as well as a radio show host, nonprofit leader, a children's museum founder and a mother in more ways than one.

Joining Patrice, we have Melissa LaHommedieu. As a social worker, Melissa's mission is to create stable homes for individuals and families in Santa Cruz County. This episode is simultaneously deeply disturbing and remarkably uplifting because of the challenges they faced, the lessons they've learned and the unbreakable bond they formed.

This episode is sponsored by MERGE4. I'm an investor in the company because they make the coolest socks. I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People. And now here are the remarkable Patrice Keet and Melissa LaHommedieu.

Patrice Keet:

I was a school counselor in Capitola. I had been a marriage family therapist in private practice for maybe ten years. A teacher referred Melissa to me. She was in a foster home and she walked in and something happened to me. I fell in love with her as soon as she started talking. It was an experience like surreal.

And the more she told me about her story, the more I thought, "I want this girl in my life. I want to help her. I want her to be part of our family." She started describing the kind of family that she wanted and had never had and had been permanently taken away from her biological family.

So, there was no chance for that happening. And the more she talked about it, yes, we have love. We have resources. I didn't say this. We still have parenting love. We had two teenagers, one in college and one in middle school. And we still have love.

And anyway, as soon as she left my office, I called my husband. "What would you think about being a foster parent to this wonderful girl I just met?" He goes, "Let's talk about it over dinner." Because we hadn't ever talked about it. We had jokingly talked about adopting a child because we both love kids.

So, we talked and it was lickety-split. Within two weeks she was living in our house. It was expedited more than the usual process because I think I knew people from my profession. And anyway, she lived with us. It was magical. I've got three children, I can't believe it.

And we had a honeymoon period that was fabulous and went on and grew to love her more and more. And then she started pushing back and separating or not joining. And she would see her mother and grandmother every month and come back very distraught from that. "You're not my mother. You'll never be my mother."

And I wasn't quite ready. I will be the first to say, with all humility, I had so much hubris when I went into this. And Melissa did things that my kids hadn't done. Naturally, she came from a whole different culture, a whole different background. She had been traumatized. And whereas I could handle things in my office when I was at home, I was like,

"You stole a wallet. Oh my God, what are we going to do?"

Guy Kawasaki:

The famous red wallet?

Patrice Keet:

Yes, the famous red wallet.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wish you've gotten bucks for finding.

Patrice Keet:

Yes, oh yeah. That may be the only funny part of the book. And anyway, I didn't handle things well and wasn't prepared. And then the idea of adoption came up. Melissa heard from somebody, maybe her social worker, that we were thinking of adopting her.

Had learned mistakenly that if she were adopted by us, she would not be able to see her biological brother who was, and I would say still the closest person to her besides her children. So, she then started acting out more and more. I don't want that. And then I took her to a bad therapist, which was a mistake.

Guy Kawasaki:

Is this the famous Olga?

Patrice Keet:

Yes, the famous Olga.

Guy Kawasaki:

Did you change the names in this?

Patrice Keet:

We changed many of the names.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, it's not really Olga.

Patrice Keet:

No.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, if I encounter a therapist named Olga, I shouldn't say, "You're the Olga."

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I would be shocked if she was still in practice.

Patrice Keet:

I don't know that, but that's not her name. So, that was probably a breaking point. Bob and I went on a vacation. Melissa ran away. When we got back, I mistakenly pushed her to ask by saying, "We love you. We want you in our family."

"We don't want you running away. Do you want to be in our family?" And she said, "No." And she persisted with that. And her CASA and her social worker listened and lined up behind that. And she moved to a group home. And that was so traumatic for both of us, Bob and I.

And Bob said, "We need to listen to her. Maybe we're not the right people for her. She may know her own mind." And he still continues to believe she knows her own mind all the time, which he's her number one fan. And anyway, so she left and we had no contact with her, which is unusual.

So, that's partly why I wrote the book to figure out why did I act so different? And essentially what I came up with was I had been rejected. It pushed old wounds and I felt inadequate. I didn't want to go through that again, being inadequate.

And I didn't know she wanted to come back. So, fast forward twenty years later, Bob and I are at a gala event at Chaminade. And I'm about to open the children's museum. I'm looking out the window. This beautiful young woman is speaking to 250 people.

And eventually we figured out it was Melissa. And we started crying and fell off our chairs. "Is that our Melissa?" From there, I ran out after she finished. Bob went and got her. We had a phenomenal reunion in the hall.

Took her out for lunch a couple of days later. Fell in love with her massively again. Took her daughters out a couple days later. Fell in love with them. They were the same ages that Melissa had been when she came to us and then left.

And so, they were thrilled to hear what she had been like as a child. Because they didn't have very many other people. They didn't have any other foster homes to talk to. Fell in love with them.

Found out during that outing that they were about to lose their housing, about to be evicted through no fault of their own. Bob and I took about a week, a day to start thinking about it. And then a week to really put it in place. We had an apartment in our other place that we could retrofit for them.

And asked her, and she was reluctant at first because she was feeling a stronger sense of independence. And short story, within four weeks they moved in with us. And that has been eight and a half years now.

Guy Kawasaki:

Not this house. Different house.

Patrice Keet:

No. Different house. Yeah, we moved here four years ago. And we only looked for places that would accommodate them. They're a family. So, we looked for places with a unit.

Guy Kawasaki:

Is there a more perfect plot line for a movie? Oh my God.

Patrice Keet:

All over that.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, I guess one question is after you ran away, you didn't run away.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Oh no, I ran away.

Guy Kawasaki:

No, not the time on the bike or you're trying to bike on the freeway. The social services were involved. They knew where you were. You didn't just disappear.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

No, they knew where I was at the whole time. But at that point, running away, it was like a tool in my tool belt. It was part of my repertoire that I had already learned. It was a manipulation tool. It was the only power play that I really had.

And so, I held out on that one. And I'd only pull it out until the very last minute when I didn't really see a resolution, when I didn't really see a happy ending anymore. When I felt all right, this is it. There's no recovering from this. And then out it came.

Guy Kawasaki:

And was there a period where you would've taken her back and she would've come back if both of you knew that was possible?

Patrice Keet:

Yes, on my part.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I don't know that I would've gone back. Yes, there was a point that I would've gone back. But it would've required me to greatly suppress a very large amount of pride at that point. And there wasn't a whole lot of things that kind of fed into my self-esteem as a young child.

And I think it would've been hard for me to say, "Yes, okay, I am going to come back. I want to try this again." Because I think a part of me knew that I couldn't meet the expectation that was being presented to me. I really couldn't.

And I don't think that Patrice could really see how her expectations were not realistic for me. Because all she saw was my potential. And she saw all of these skills that I have and all of this progress that I had made. I didn't learn to read until very, very, very late.

It was after I was already removed from the care of my biological family. So, I was seven and a half when I was taken away. I was still living with my paternal aunt when I learned how to read with her. And you think about that's between what the age of eight and nine?

That's pretty late on. And so, by the time that I ended up with her, I was very far behind. And I made leaps and bounds. Even though I wasn't necessarily always getting good grades, there was a lot of catch up that I had done. From her perspective, it was like all of this potential, all of this talent, all of this skill.

And she wanted to facilitate the growth of that or kind of like a catchup, I guess. And I think it would've been difficult for her to see what kind of was hidden underneath that. And why it wasn't realistic for me to catch up to the level of a child who had been born into that amount of support and had been born into that healthy environment.

Patrice Keet:

But I think there is a sort of almost Shakespearean tragedy about that. Because we would've definitely taken her back. And if we had help, ask for help and gone to therapy together as a family, and Melissa could have said some of those things.

And I already was humbled by the fact that she ran away. So, I have eternal optimism that it would've worked. And when I found out from her that she had been taken back to other foster homes. That was the standard. Run away, then you get put back.

Run away, until finally they get sick of it. That she expected that even if she didn't think it would work out, that at least that would happen. And I found that out in the midst of writing the book. And like, oh my God, really she was waiting for us.

Guy Kawasaki:

And why didn't it happen?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I don't know. I have a feeling, an inkling that they were afraid to do because the previous time that I had run away, there could have been legal repercussions against them for placing me back in because they didn't listen to me. And that was very extremely abusive, and they ended up losing their license. But I didn't tell anybody about that. I had to run away from that home three times.

Guy Kawasaki:

This is the Larsons in the book?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

The names are changed. So, it's the first home that I come to live in Aromas when I am sent away from my paternal aunt. And that's the home with the sexual abuse and the physical abuse and the locked cupboards. Which don't get me wrong, the locked cupboards were standard in a lot of foster homes.

But the level of abuse in that home was not standard for a lot of foster home. It wasn't until several months after I was removed and I divulged the information to my counselor, who I saw once a week and then that facilitated them losing their license and the children that they had guardianship over being removed from their home. So, I have an inkling that maybe they were like, "Maybe we shouldn't send this one back just in case."

Guy Kawasaki:

But that stepfather or father was not a stepfather. But that guy never was criminally prosecuted?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

No, he wasn't. He never received any criminal charges to my knowledge. That's not the way that it was explained to me. The way that it was explained to me is that it was conducted in a very kind of hush, let's dot our i's and cross our t's type of way.

But mind you, I'm a nine-year-old kid. So, this is just what memory is available to me. But I do remember being very angry about that. Because in my mind I'm like, "Wait, that happened to me and my stepdad went to prison. And then this happens to them and nothing happens. They're just taken away."

So, it just didn't line up. I think you have a concept of what's just and fair from a very young age. And in my mind, I just felt like that's so unfair. That's not right. It made me very angry. And the fact that I wasn't sent back, it could be a lot of things.

It could be like, "Oh, she's just going to run away again." It could be that this one's a liability. It could be that we think the foster or a group home setting is more applicable to her.

The point is, I don't know, because these things weren't communicated to me as a child. Nothing was communicated to me. So, we're only left to speculate at this point.

Guy Kawasaki:

And if someone were to read just this book to get a window into foster care, it is not a pretty picture. There's stuff in this book I could not believe. And that just shows how lucky I've been and fortunate and protected.

I freely admit that. But holy shit, I could not believe some of the stuff that you wrote. And really I do not understand how you did it. How you survived it, much less how you wrote about it.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah, I think that is a common response. It is definitely a common response for people to have shock about what the foster care system experience is really like. And it's really interesting. Because when you think about a lot of the stigma that is carried by foster youth, at least particularly what I experienced and why I learned not to divulge that information so freely to people, was that you're very quickly painted as a bad apple.

There's a lot of negative associations for children who are in the foster care system. So, it's really interesting to me that it can be accompanied by all of these negative stereotypes. But nobody sits and questions, why are these children acting that way? What's wrong with this scenario?

But your response, it's very common. I don't think I've ever met anybody who's like, "That makes sense." And I have yet to meet a foster child. And also I have to make the distinction between growing up in the foster care system and being illegally adopted.

They can be similar experiences, but they can also be very different. But I have yet to meet a child growing up in the foster care system who has had a positive experience all around.

Guy Kawasaki:

Not one?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Who can say, "Wow, my experience in the foster care system was great." I have not met one foster child who said that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. So, I mean, are you telling me that many or most foster children are abused?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I'm not saying that most foster children are abused or experienced the same level of trauma that I experienced in the system. But the very fact of entering it is traumatic in itself. And there may be a foster child out there who's, "I disagree with that."

That may be a response that we get and says, "You know what? Mine was great. And I would applaud them. I think that's absolutely wonderful. But the point of making that statement is that there's inherent flaws in entering the foster care system. The very fact of being placed in it is traumatic in itself.

So, you're already off to the negative and traumatic start. And even if you come in and you find a completely appropriate placement who doesn't have any marker of legitimate abuse, think back to your own childhood.

Was your own childhood absolutely fantastic and easily navigated and you never had any issues with your parents whatsoever or having them enforce stuff? You complicate that by the fact that there's no relation that says this is the way it's supposed to be. You always fall back on that, you're not my mom.

You can't make me do anything. It's just further complicated by external factors. And so, it inherently alters the experience. And I've even shared parts of my story with people who have not been in the foster care system.

And at one point somebody said, "Even if you hadn't been in the foster care system, you can still experience a lot of these things." I said, "You're absolutely right. You can experience a lot of those things." But the way in which you experience them would be very different.

Because there's an inherent sense and idea that you belong with where you're born. You belong with your family. And that sense of belonging is interrupted when you're removed from your home.

Guy Kawasaki:

And do you still think you belong with your biological family?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Oh no. Not whatsoever. But as a child, I understood that's the natural law that I'm supposed to be with them. So, when I talk about belonging, no, I didn't feel like I fit in with my biological family. But I knew that's where I was supposed to be.

I didn't question whether or not that was what was right. That there was a belonging, that there was a reciprocity there. Did I question what was happening to me, whether or not that was right or wrong? Absolutely.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, if someone listening to this and thinks, "I belong with my biological family who's abusing me." What would you tell that person, this kid?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Honestly, I wouldn't even want to challenge that belief. Because belonging isn't necessarily the problem. And the messages that I received around my family were very different than the messages that are portrayed I think in a lot of ways today.

You have to keep in mind that this is years ago. I'm thirty-nine today, so it's been thirty years of mistakes and lessons learned that have been applied into the foster care system since I was in it. And so, no, I wouldn't challenge that sense of belonging and that sense of mis-justice.

Because what they're expressing when they say that I don't belong here, they're expressing a mis-justice that they've experienced. This is unfair. I should be with my mom. I should be with my dad.

And so, my response wouldn't be to that. It would be into the parents' ability to care for them and care for themselves. But that wasn't really the approach that was taken. That was the conversations that I had with my kids.

And it was just in relation to their biological father. When they say, "I wish I had a dad." And I'd be like, "Oh, you do have a dad. I wish he was around too." “Why can't he?” “He's not really healthy. He can't really care for himself. It's really hard to care for somebody else when you can't care for yourself. But it doesn't mean he doesn't love you.” That's a very different message than saying, "No, you don't belong with your family."

Guy Kawasaki:

Do they see their father at all?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

He actually passed away last May. May 1st I believe, or March 1st.

Guy Kawasaki:

As I was reading the book, I have to say, I asked myself about ten times, "Did she leave anything out?" Oh my God.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Oh yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

There's worse stuff?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I try not to get into adversity Olympics, but there's a lot more stuff is what I would say. Yeah, there's a lot that was left out. I think you could probably speak to the kind of thought process that we had and what we kept in and what we kept out and try and create a balance and a flow in the book, and also protect the reader a bit.

Patrice Keet:

What I gather from you is that there are things that you didn't even put on paper. There's a backstory. That's what you mean. We edit out maybe two rounds of going back to the mother-in-law.

It impeded the story. Oh, you're going to recycle back one more time to Salinas or wherever they are. And so, in my opinion, there was nothing lost. But you're asking, I think, is there more to Melissa's story that was too hard to tell or didn't get in the book?

Guy Kawasaki:

And you can tell me yes and not give me the details.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

If you're telling me there's even more, I'm telling people who are listening to this, there's a mind boggling amount in there. It is fucking mind boggling.

Pardon of my French. It's the only way I can say it. Really just the evil that you encountered in your life. There's no other way to put it. It's evil.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah, there's a lot of misfortune. I always put it in the term like a catchall that I use is I say, "I've had a really long life in a really short period of time."

Guy Kawasaki:

You've had several lifetimes, yeah. So, how did you break the cycle?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I think I still am. I think that's going to be a continual journey for me. But in a lot of ways, I've made huge strides and I've accomplished a large aspect of it. And I think a lot of it for me was around education. A lot of it was around building a healthy support system.

Obviously my parents played a huge role in that. And then I was also able to take that and extend it into other chosen families. So, like the friends and people that you bring into your life and keep around.

Guy Kawasaki:

When you say education, you mean formal education?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Formal education was really important for me because that was the pathway that I identified for myself. And not everybody can say formal education is the right answer for me. Because a big part of my story is poverty.

That was a huge factor. And people can navigate out of that, and there's many ways to accomplish that. And it depends on the individual, but I always knew that the formal education system was the right path for me. I was good at school.

And people tend to enjoy things that they're good at. And so, I was able to identify that early on. And then also, I'm ambitious. And the career that I'm interested in, you can't really get there without a formal education.

If I walked up and I just had my GED, which is all I had before I went back to college, nobody would consider me as a social worker with just a GED and lived experience. So, in that aspect, yeah, it played a huge role. But then in addition to that, my background is in psychology.

That's what my undergrad is in. And so, going through the process of understanding human behavior, you can't help but tie it to your own personal experiences because that's how you relate to the world and other people. There was a learning process in that as well that was not necessarily formal, but facilitated through my formal education.

Guy Kawasaki:

But if let's say a person listening to this is living in the kind of conditions you were. Whether it's a foster family, that was what you experienced after you left Patrice and Bob. And this person is wondering, "How do I break the cycle?"

And I don't think for many people they can say, "Oh, Melissa said go to college. I can't go to college." So, at a really tactical level, what does this person do who's trapped?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah, it's just not as simple answer. It's so individualized. It really depends on the person. I think for me, there was really distinct decisions that I had to make along the way. Even before I decided to go back to school. So, school, that was a long-term goal.

But there were choices that I had to make all along the way. And I had to stay dedicated to it. And I constantly had to weigh out, okay, what are my choices here? How is this going to help me to get to that end goal?

So, I was constantly having to weigh choices. But it wasn't always in relation to school. Sometimes it was in relation to how do I get out from under the thumb of my ex-husband and his family who were extremely controlling to me and very abusive?

And so, sometimes the decision was, do I work with the current CPS case that's opened against us? Because we had another screaming and yelling argument and the neighbors called the cops and we got another referral back to CPS. Should I open up to them about what's going on?

Or should I keep it a secret and just keep working on my own? Should I tell my CalWORKS representative that I need my childcare? How do I keep my childcare without telling them that my ex-husband is using drugs and is disappearing for days on end and that's why he can't be a caregiver? But without losing the benefits that I receive.

Because a lot of what I'm receiving is paying to support him as well. And without supporting him, I had nowhere to go. So, the option was do I tell her he's not really participating as a parent at this point because he has a drug addiction?

But if I did that, then I would lose all of the aid, the what? $200 of aid that I was getting for him. The whopping $724 to support a family of four. So, you take $200 of that away while I'm working, while I'm going to school, while I'm doing all these things.

These are the type of decisions that you have to make. And so, I can't just say, "Oh, do this one thing." But I guess the answer would be you have to sometimes weigh your options against what your long-term goal is. And so, a lot of the times, both those options are bad.

I think that was one of the messages that I was trying to get across in the book is, yeah, I made a lot of bad decisions in my life. But I wasn't always presented with any good ones. And when your choice is two bad decisions, you're going to choose a bad decision.

Guy Kawasaki:

And as you said, this was a long time ago. Do you think those kind of decisions are still forced upon people where if you report something, you lose money?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Oh, yeah. Absolutely.

Guy Kawasaki:

Is there a way to fix that?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Not necessarily. It would have to happen on a federal level. That's essentially what determines all of this aid. So, it's federal policy that determines how much aid people receive who are receiving social services. And it's also used to determine how long they can receive the aid.

It's used to determine what the qualifications thresholds are. And so, we would have to facilitate a major movement in reeducating and going against mainstream beliefs, which tend to be highly conservative. And moving away from the view that the problem is inherent in the individual.

And something is inherently wrong with them to where they can't support themselves, to being able to look at a much broader picture and looking at ways in which the system can adapt to serve their needs, so that they can become functioning parts of society. Because essentially, when I think about my success, that's essentially where I'm at. I'm a functioning member of society now.

And I'll always have more work. And even if it's just maintenance, the same way that you maintain a brand new car, we do that for ourselves too. But that's the end goal. We all want to be well-rounded whole people who feel like we have a purpose and can support that our dreams and our goals, and contribute to others.

Guy Kawasaki:

You have insights on how to break the cycle, Patrice?

Patrice Keet:

I think that not everyone who was in the situation that Melissa was in will get as lucky as she did. And you say that too, right?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah, absolutely.

Patrice Keet:

And I think that systems change needs to happen on so many levels. We need to have more foster families. And as David Ambroz in his fabulous book and podcast talks about why not retrofit unused government buildings into dorms for foster youth to go to college?

They need support. And luckily now there's new legislation within the last ten years between eighteen and twenty-one. But at twenty-one, a traumatized young adult does not have the same skills that a child who came from an intact family with resources has.

So, they need more education, more educational opportunities. Foster families need more incentives. People said to us, "Why are you doing that?" We had to say, "We want to. It feels good. We love children. We want to make a difference."

Not everyone's going to have that inclination or that ability. On a personal individual level, I believe that let's say someone, a child like Melissa is a cup. And that we all as a society have responsibility for how full she is. Because we in some ways facilitated her being born.

I guess I'll start back. Number one, parenting has to be a choice. In this country, we have to make it so that parenting is a choice, not a default result of a mistake someone might've made. So, that's where we start that parenting is a choiceful.

And we all know who are parents, even in the best of circumstances, it's a challenging thing to do. So, if you don't want to be a parent and you're forced to be a parent by your society, we're off to the wrong start. After that, a child who is in an abusive neglectful situation needs adults around them to be looking at them.

I like animals. Not as much as most people, I have to say. But our society loves animals. And if they see a hungry animal downtown or they see a hungry animal.

Guy Kawasaki:

Or a whale.

Patrice Keet:

Or a mistreated whale. How many rescue services do we have?

Guy Kawasaki:

Millions.

Patrice Keet:

And do we put those same resources into children? No, and it's very curious. And I want to do much more thinking about why that is. I guess the whole parenting relationship with kids is much more complicated.

You can't just grab them out. But we all need to have our eyes on how well children are functioning, the teacher, the social worker. And we need to be willing to intervene and say, "There's something wrong there."

Yeah, that's a hungry child, and I'm going to do more than just give them a snack at school. It's a societal responsibility. Otherwise, it becomes a societal liability, which we see. So, we need more government intervention.

We need more money to the foster care system. We need foster parenting to be raised up to a level like we need teachers to be more recognized and valued.

Guy Kawasaki:

No kidding.

Patrice Keet:

And same thing with foster parents, so they may need incentives. As David Ambroz again says, "Why not give them supplemental incomes or benefits like their own children can go to college for free or community college?" So, there's that.

But back to the cup analogy. I think that not everyone's going to take a family into their home and a young person into their home like we did. But we can all donate clothes to Hopes Closet in Santa Cruz or somewhere, leftover clothes.

We can pick a charity and put a little bit of extra money in that. We can foster legislation and help that way. So, my belief, and I'm an optimist, is that as we look at and touch into our generous spirits, we can make little bits of differences that eventually fill up, say, Melissa's cup.

And she spills over. And look, she is spilling over. She is generative. She is making the world a better place as are her kids. Her cup got full enough. And there are ways that we can do that. Our priorities are wrong. We have plenty of military spending. People spend money on sporting events. They spend money on concerts.

Do we spend money on a hungry child? I maintain my optimism that we are basically good and that we will come to a realization. And that there are improvements. Melissa's on the CASA board, I was on the CASA board.

We both believe very much in that organization as mentoring and a bridge for foster children. And when parents cannot always take care of their children, that was the case with Melissa, for a bunch of reasons. And the society needed to do that and failed her many steps along the way.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you think Universal Basic Income would've helped?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

It depends. I think fundamentally, UBI is a positive concept. It's a step in the right direction. But am I confident that UBI would be implemented in a way to where it provided enough support to meet basic needs?

If Universal Base Income was enough money to fundamentally cover basic needs, I think it would facilitate a lot of growth and improvement. And that's just fundamentally based off of what? Maslow's hierarchy of needs.

When you have your essential needs met, it allows you to look beyond that and facilitate growth in other aspects of your life. And so, yeah, I think that's something that I have considered. And I think that I would be on board for, depending upon how it was implemented.

If it's implemented in the same way that our current welfare, what's commonly referred to as our welfare system, is implemented, then I don't think that it would be effective. Because welfare isn't implemented in a way to where it allows people to meet their basic needs.

It's just like, "Here, we're going to give you a little extra. We're going to give you a little something because you're so far away from meeting your basic needs." But it never balances it out and brings them up to where they can start thinking about, "Oh, cool, I have a roof over my head."

"I have food. I have clothing. I'm not going to die of hypothermia in the cold. I don't have to think about getting my very fundamental, basic need met the next day." That's when you can start looking beyond and saying, "Okay, what is it about myself that I want to work on?"

"What is it that I want to be? How do I want to contribute? What type of life do I want to provide to my children?" It's really stressful being poor. And when you're poor, it's hard to parent the way that you want to.

I think anybody can look back on just a bad day at work and coming home. And who's the first person that you usually take it out on? It's the people that you're closest with. And it's just because you just don't have the capacity in that moment.

So, when every single day is like that, it just piles up and it piles up more and more. And it suppresses your ability to be more, to look inward, to give.

Patrice Keet:

So, to think of a solution for that, we need more parent support. We need parent support groups. We need foster care support groups. And Melissa at one of our talks came up with what I think was a great idea, which is mentoring for foster parents.

I believe some foster parents do it well. And I understand that you haven't had the experience of knowing the results of that. But the ones that do it well and have had positive outcomes should be there to mentor. And that should be a mandatory thing.

I think for foster parents, you're going to meet with people who know how to do it. It's like a grandmother. And societies historically have worked because there's a clan, there's a community.

Guy Kawasaki:

And what if someone listening to this is considering being a foster parent? What would you tell him or her?

Patrice Keet:

I would say, look at what your motivations are. Look at what your resources are. Are you a single parent already and a little stretched? Don't give up on the idea, but try to enhance your support system.

Because it's hard enough to raise a child alone. And some people have that ability. They have the internal resources, the external resources. But find out more about what it's like.

Talk to other foster parents. Talk to social workers. And look at what your motivations are, what your resources are. And then maybe take that leap and step into it and learn.

Guy Kawasaki:

What should be your motivations?

Patrice Keet:

We'd have to go back and say, "Why do we have children?" And part of it is to get love, to give love. It's like CASA, the court appointed special advocates. They do an extensive training and evaluation of people to figure out what their motivation is in becoming a CASA.

And if it's all about meeting the adult's needs, then they're screened out. So, I think that could be implemented. Right now there's a shortage of foster parents, so it's not as selective. I think if there's a larger pool, it can be more selective.

And there can be a way of saying, "Why do you want to do this? And what do you think? And how's the rest of your life going." And all that. And then when they become foster parents, they need training.

They need skills training, specific conflict management. They need to learn the developmental stages of children and developmental stages of traumatized children. What are going to be the unique things that a traumatized child brings to your family? And then the family needs support.

I remember it is in our book, my son Colin said to me at one point after Melissa had been with us for maybe a half a year, he said, "When is she going to become a Keet?" And I knew what he meant. And then I deconstructed it a bit.

And it was like, "Oh, she doesn't play with Barbies and doesn't eat meat." There were very superficial things. And he was well-adjusted, and he was fine with having Melissa, but I had to educate him. I never told him the details of what she had been through.

But I had to say, "She's different. It's okay." One time he said she's bragging and she's going to lose friends that way. And I said, "It's okay if she brags. She hasn't felt good about herself for a long time. Let's give her the place to brag."

So, a foster family that has children in it, biological children, needs support as well. They need some education too. So, let's shore up families in general and let's shore up foster families especially.

Guy Kawasaki:

My wife and I have adopted two children.

Patrice Keet:

I did not know that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah, so we have two children adopted from Guatemala. And it has been a beautiful experience. It is one of the most, maybe the most, important experience of my life. And probably my wife would say that too. In fact, I'm sure she would say that too.

And I remember the adoption process, the questions and the research and the screening that we went through. If biological parents went through that screening, there would be a whole lot less kids who are not loved.

Patrice Keet:

Absolutely.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, we talked about breaking the cycle. The question I have to ask you, Melissa, in particular is just how do you deal with trauma?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

That's a good question. I guess it depends on the type of trauma and what stage of dealing with it I'm in. If it's an emergency situation, somebody's been in a car accident, I see somebody get hit by a car. I'm probably going to be the most levelheaded person there. And the calmest out of everybody and able to call 911.

But then after that experience, when everybody else is coming back to their senses, that's when my trauma sets in and I start processing. And I'm like, "Wow, that was really crazy." And there's a little bit of shock that comes in.

And I think for me, it takes me a little longer to come out of that than other people. So, what I'm saying is there's pros and cons to the way that I've been socialized to experience trauma. In some ways, it's really helpful and it gives me an advantage if I'm able to harness it in certain ways.

But then in other ways, it really is a disadvantage. Small things can set me back for a really long time. And so, it really just depends. I think one thing that I tend to rely on most predominantly is that I tend to process things through verbal communication.

And so, when I've experienced a trauma, I seek out people that I trust so that I have someone to help me process that. And it's not necessarily like I'm going to them and I need your advice what to do. But more or less just having somebody there to help me work through it on my own. I think that's one of the ways that I process trauma.

Guy Kawasaki:

It's some of these questions I don't even want to ask, but I want to take the extreme case. You're being sexually assaulted.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

By my stepfather. And many others, yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

And many others, yeah. How does one deal with something like that?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah, that's a good question. So, I think the initial tool that happened for me, which is really common is dissociation. So, dissociation, it makes it to where you detach from your feelings. And you look at yourself, it's like a de-realization and a depersonalization that happens where you don't really feel like what you're experiencing is real.

And then that's the de-realization. And depersonalization is it can be expressed as somebody looking down on an event happening to them. And even though they know it's them, there's no emotional connection that's happening to it. That's essentially a foundation of dissociation right there.

And I think that was an adaptive mechanism to help me get through it while I was experiencing it. And then after I was experiencing it, it presented in behavioral outbursts, which is really common for young children. And I'm not really sure how I managed that.

But there was a few things that were maladaptive that I can respond to. And a lot of them, it was like an escape. So, I would experience something and then I would want to sleep an exorbitant amount of sleep to process. And it's like an escape tool.

And then I've processed it in so many unhealthy and then healthy ways. Eating is another one, like eating feelings. That's a really common one. And then writing. I started writing poetry. Just writing in general was really cathartic for me.

Guy Kawasaki:

You never used drugs as a way to deal with trauma, to escape?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Not initially. It's hard to say yes or no to that. I think that my relationships with drugs, I couldn't necessarily relate to the same way that it was expressed by people who identify as addicts. Where they're like, "I just can't say no to it. I need to have this."

My relationship with drugs, it had some sort of function to it. And then once that function was no longer there, then I wasn't really interested in it anymore. And so, I don't know. It's hard for me to say.

Guy Kawasaki:

In the book, there was a part where you said that you were taking meth so that you could stay up so that you could protect your kids. And my head exploded. That's kind of a rational thing, honestly. You took meth so that your kids would not be harmed so you could watch them twenty-four hours.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Right.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm still putting pieces of my brain back in my head after I read that. That was unbelievable.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I can tell you that's actually a fairly common experience. It's a fairly common experience that has been conveyed to me in my case management and social work and working with particularly women who are homeless, street homeless.

Many of them will resort to drug use for that very purpose because they have to stay up to protect themselves. Whether it be from theft, whether it be from sexual assault, whether it be from physical assault. But it's not a super uncommon motivator.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, let's say that your friend confides in you that they're being abused, they're being assaulted, whatever. And this friend who has the best interest of the person at heart has this very difficult decision, which is, I want what's best for her. Do I report this?

But if I report this, she may be taken away from this foster family. She may be separated from her biological brother. Who knows what's going to happen if I report this. And the person is telling me, "Don't report this because I don't know what's going to happen."

"Maybe my next family is worse than this family." So, what is this well-meaning, well-intentioned person supposed to do? What is their decision process? Do I report? Do I just let it go? What do I do?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah, I guess this kind of reminds me of a similar scenario in the book where I'm in the foster home, the very abusive foster home, and I had made it an alliance with Rochelle. And she had shared information that she was being sexually assaulted by the foster father and her family. And had confided in me that there was a history.

There was another older girl in the home who had also been sexually assaulted by him. And she didn't want me to share that with anybody. And I actually grappled with that for a really long time. Because the way that I grew up was honoring that or withholding that information was a representation of our friendship and my loyalty to her.

And it was really difficult. And that's actually sharing that information with my counselor is what facilitated that foster family losing their license. And I grappled with the exact same concerns. “Oh, she's going to be so upset with me. What if she goes somewhere different?”

The short answer is, I don't know. I can't answer that for anyone. I think for me, the reason that I ended up sharing it was because first of all, I had the support of a therapist helping me to work through some of these conflicting emotions and concerns.

But ultimately, it was the decision for me to share that wasn't out of loyalty to Rochelle. It was like, what about the next girl who goes in there? That was the position that I was in. So, I think that for me, when I'm struck with really difficult decisions, I have to separate myself from the personal connection of it, take myself out of it.

It's not all about Rochelle, it's not all about me. But if I don't share this, then I'm allowing another girl to go into that situation and potentially be harmed. And that's why I ultimately shared that information. So, I don't know if it answers your question or if it's going to help anybody else, but that was the thought process that helped me in that scenario.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you have any insights into this thought process?

Patrice Keet:

I think that in every group, including a group home, there'll be a bonding, as Melissa's saying she did with Rochelle. So, it was hard to figure out what would be best for Rochelle. And again, David Ambroz was so amazing that he so often was asked questions.

And he lied because he was afraid that it would get worse. And he was asked in front of his mother, which was egregious. And it did get worse. There should be protections for people, and there should be enough supports, including therapists.

And a sense of, I don't know, I guess right and wrong. I think that for you, Melissa, it was in some ways the family culture of your biological family. You were told to lie. You were not supposed to tell the truth because it would break you all apart.

And all you had was each other. And to have that broken apart, you didn't know what that would look like. You didn't know if it would be worse. You didn't even have the luxury to think that. So, you stayed as you did with your husband because it looked scarier to not stay.

So, we as a society need to provide that picture that it can get better. There are resources for people. And that this is not the way to live. And it re-traumatized you from your earlier experiences to see what was happening to her.

So, you, at some point, had to take care of yourself too. I don't want to be the victim again. I don't want another person to be the victim. When you took the moral high ground, which is a great place to be, I think in this case where you protected her, yourself, and as you said, other children.

So, it's so hard to break that loyalty bond though. And to change the thinking that I can tell the truth and the truth may save me, it may save other people. And in his case, David's case, it was almost death that made him realize, "I've got to get out of this."

"I can't protect my mother anymore. I have to protect myself." And I don't think there were enough other adults in his world. And I don't think there are in most foster children's worlds who can say to them, "You're worth more than this."

"You don't have to live this way." And he didn't know that there was another choice. He just knew he couldn't die.

Guy Kawasaki:

Bottom line, Melissa, thirty-nine years old now, did the system work for you?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I guess.

Guy Kawasaki:

You could tell me it didn't. I don't know.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I don't know. I think it's pretty clear the ways in which it didn't work. But I think astounding about my story is that I found ways to make that experience work in really positive ways for me. My outlook supports my growth in a lot of ways. Is it easier for me to look back and say, "Oh my gosh, that was horrible."

"There was nothing to have been learned from that." Or look back on that and be like, wow, "I may not be the person that I am today without those horrible experiences, and I really like who I am." And I chose the latter.

So, I guess in a sense, it worked. In a sense, there was a positive outcome for it. But I think for many people there's not. And that's the enigma to the story is we don't know. We don't have the formula where we're able to identify a lot of key recipes.

And there was a lot of key recipes and maybe certain attributes that I was born with. There was a key recipe is a lot of luck. A key recipe was certain events that facilitated this, just astronomical reworking of my psyche in those moments. And so, there's key ingredients in the recipe.

But we don't know the whole formula. And you can take key ingredients and put them together. But it's still without the little guys, the little things, like that little dash of salt or a little baking soda to make it rise properly. You're not going to get a whole cake.

So, I like to think that it worked for me because that's what helps me cope with it. Otherwise, I think it would be really easy to get lost in those traumas when they resurface.

Guy Kawasaki:

But, Melissa, for every successful Melissa, how many people got ground up and spit out?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Too many.

Guy Kawasaki:

You're the exception.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I'm certain I'm not the only one though.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Patrice Keet:

He didn't say the exception. You're an exception.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I think that my story is an exception to the rule. But that's part of what motivated me to put this into writing in the first place. And not just for foster youth. I think a big aspect of it, because such a huge part of my identity is being a former foster youth.

It shaped a lot of who I am and how I relate to myself and others. But there's a lot of other things in there too that are separate from that experience. There's poverty, there's substance use, there's codependency, there's domestic violence.

There's being a single mother, there's being first generation college student. There's a social mobility, there's internal growth process in coming of age. There's just so many other things that are wrapped up into the story.

And it's because of all of those that I wanted to share it with people in the hopes that they could relate. And it's been an amazing tool in being able to relate better with my family as well, particularly with my mom. And oh, to clarify, when I talk about my mom, I'm talking about Patrice.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah, that should be obvious.

Patrice Keet:

Which wasn't always the case.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

No, it was not always the case.

Patrice Keet:

I would say it's how long?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I don't know. It just melded into this organically.

Patrice Keet:

Would you say years, months?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah, using the term mom I think it started with relating to us as family. And then relating to you and Bob as my parent. But I can't really pinpoint where it was, but it was very natural an organic process, coming to refer to you as my mom or Bob as my dad or as my parents. And it was just very gradual.

Guy Kawasaki:

I mean, at this point, Patrice is mom, Bob is dad. And when they introduce you as my daughter, not my foster daughter.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

There was a period of time where we did though. And it would teeter back and forth. Sometimes it would be daughter and sometimes it would be foster daughter. And I did the same thing with them. Actually, I wonder if you have that platter that I painted?

Patrice Keet:

Yes.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Oh, we should find that and show it to them. So, the girls and I went down to Petroglyph for one Christmas, I think it was like two years ago.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, the place where you paint?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

So, my mom loves entertaining. She's really good at it. And I was like, "Oh, I'll paint a platter. So, they had this platter down there." And I did this platter and I wrote in cursive on it this really funny thing about how we relate to each other as a family. We'll have to pull it out and show it to you at some point.

Patrice Keet:

Yeah.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

It's really funny.

Patrice Keet:

Yeah, it's very lovely. And it's not simple. It's not simple raising children. It's not simple raising a child that you didn't have a start with. So, there were missteps along the way. Both of us have had trouble attaching, I think I'd say that's fair to say.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

And then she disappeared for nine years.

Patrice Keet:

Twenty.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Twenty.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, twenty?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah.

Patrice Keet:

Twenty.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Disappeared for twenty years.

Patrice Keet:

Yeah, and we found out that they were going to be homeless and that she wouldn't be able to meet her dreams. Because when we went out for lunch, I said, "I know you always wanted to go to school. How far did you go?" And I think you said, "I've taken a class at Cabrillo."

Melissa LaHommedieu:

No, I had taken a year and a half at Cabrillo.

Patrice Keet:

Oh wow. On your own. Holy moly.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah, I had taken a year and a half at Cabrillo. And I had to take a step back because I got a promotion at work. And that's why I actually had left Carl’s Jr. to go to Burger King because I was trying to fit that back into my schedule. And Carl’s Jr. wasn't willing to accommodate that.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, when you ran into her at this speech, that was twenty years from the time she left?

Patrice Keet:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

With no contact?

Patrice Keet:

None. No, she had gone into Bob's office to see another doctor in his office. Right. And he came home and told me about it, and I was just completely discombobulated.

Guy Kawasaki:

What year was that?

Melissa LaHommedieu:

2008.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, how many years had you been gone?

Patrice Keet:

So, twenty. We re-met in 2014.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I'd have been twenty-four at that time.

Patrice Keet:

It had been twelve years, and she wasn't in a good place. And I, for a lot of reasons, just wasn't willing to reengage. She wanted to get out of his office as fast as possible.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Oh yeah. I couldn't get out of there fast enough. It was horrible.

Patrice Keet:

It wasn't she said, "Oh, come tell me. I want to go see Patrice. Let's get together again."

Guy Kawasaki:

So, she walks out, twelve years go by and goes into Bob's office by mistake.

Patrice Keet:

Happenstance.

Guy Kawasaki:

Then another eight years go by and you see her making this speech.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

You find out she's about to be homeless and bada-bing, bada-bang, she's back.

Patrice Keet:

Yeah, we had a second chance. We got redo it. There was some psychological block of not knowing who she was immediately when she was standing in front of the 250 people giving a speech about her life. I'm looking out the window like, "Where am I going to get money for the Children's Museum?"

"Who am I going to hire? What the hell am I going to do to get this project moving forward?" And I just wasn't paying attention. At some point, there were enough identifying pieces of information where we said, "Is that our Melissa?"

I waited until she was finished. I ran. I said, "I've got to go Bob. I've got to get out of here." I ran out. I tried to call my other daughter and say, "Am I okay? I'm okay." Because it brought up all the shame and the failure, and I can still feel it right now of having failed her.

I was a successful therapist, a successful parent, successful member of the community, and I couldn't keep a foster daughter. And I couldn't make our life work together. And I was so full of shame. And I just had to look at that and look at myself. And so, I just ran out and I needed affirmation.

And couldn't reach my other daughter. And finally Bob brought Melissa to me. And she came running down the hall at Chaminade and I had been dragged out of the bathroom. And Bob said, "Are you ready to meet Melissa?" And I said, "I don't know if this is a good idea."

And she came running up to me, buried my head in her hair, which was really massive and beautiful, and we're cheek to cheek. And she said, "I'm so sorry I hurt you. I love you so much. I never should have left." I collapsed into her.

And like it was written. Some of the other aspects of our story, they just came that it was like a script. I say to the higher power or whatever, write me a script that will make me feel okay, that will make me feel validated. That will make me feel close. That will make me take away my shame.

Guy Kawasaki:

You can ask ChatGPT to do this now.

Patrice Keet:

Exactly. She must have done that because it was perfect. And from then we just started sharing our stories. Man, I literally get chills now about that experience. Because it was like, yes, all those things are true. I was hurt.

You had some part in that. I'm not giving you all that, but I love you. I love to hear that you love me. And yes, you should not have left. Evidence is proving you should not have left. But now we know it. So, it was already, wow, how are we going to get more of her?

Are we going to get back with her? Not to live with us. I had no idea about that. But just make it right, make peace with this person that I loved. And then her daughter spilled the beans when we were out on our sailboat.

Guy Kawasaki:

That you needed a house?

Patrice Keet:

That you were getting evicted. And it was against Melissa apparently. I was out with the other daughter. But apparently, according to Bob, Melissa blanched tried to shut her daughter up and said something like, "It's fine. We're always going to make it."

"We're going to be fine. Don't worry about us”, and make her daughter feel okay. But Bob, when he got in the car and told me what had happened, I was speechless just like we had been when we met her at Chaminade. And I just rode home and tears running down my face.

And right after that, we went out to a restaurant and we were eating dinner. And Bob said, "I don't think I can ever go out to a restaurant again. I'm picturing them hungry. I'm picturing them unhoused. I just can't do this. I can't do this." And we both knew where it was going.

We both knew where it was going to see if we could reconnect and help again. And yeah, could I spend a minute sharing what I learned as a foster parent?

Guy Kawasaki:

Of course.

Patrice Keet:

I would say to a person who starts engaging in the process of being a foster parent, slow down, chill out. I was so unchill. Like Melissa said, I encountered this nine year old. I could see this potential. She was so bright and so articulate and so amazing. And I just wanted to catch her up. And I ran rough shot over her past. I thought, "I want to put a force field around her past."

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, you refused to look at her file, right?

Patrice Keet:

I went that far.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes.

Patrice Keet:

I went that far. And that was well-meaning in my world of I want to give her a refresher. I don't want to know what else she did. It was so misguided. People out there, please read the file, get to know your child.

Get to know them, and slow down. And get to know who they are. You don't necessarily want to have abusers in your house and visiting, but let their past be real. They have to process it just like in therapy. And I was so bent on the idea that we had the secret sauce.

We've got this thing that we can do for Melissa and just bring her on. So, instead of building a bridge from her past to us, culturally, economically, everything, almost everything, I just chopped it off. I put the moat. They're there, we're here.

You've got a new start. None of that. And we've been better with her daughters in letting their past organically come in and asking them questions and finding out what their past is. But foster parents out there, slow down. Get to know your child.

Meet them where they are. Don't try and take them too fast to where you want them to go. And that is not true for all parenting. We have agendas for our kids. Because well-meaning, we want them to be happy and successful and enjoy life.

And sometimes we're in too much of a rush and don't let them be where they are. And so, it's a process that we were continuing to learn for me to let Melissa be where she is. Making missteps, even as a thirty-nine year old, I hope she allows me to make missteps as an older woman.

And so, there's just a lot. And I used to teach parenting classes back in the day as part of my job. I have a desire to share with the world what I've learned as a foster parent. And I'm hoping that this book will go in that direction of helping foster parents, not they'll have to do it the hard way.

Learn from some of my experience. Just like, Melissa, your intention is to have people learn from your experience and learn that there's hope. There's hope at the other end. There's hope for a foster family who's tried it twice and got it right.

We believe in our story and what actions people might take. They might say, "I'll take a chance too on a foster child. I'll take a chance on keeping my eye on that child who's not doing well, who needs extra help."

Guy Kawasaki:

What I hope people understand there's humongous problems. And you think, "What can I do?" The old saying about there's so many starfish who are dying on the sand, and you picked up five and threw them back in the water. What difference does it make? What it does make a difference to the five starfish and you made a difference to this starfish.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Right, yeah.

Patrice Keet:

And our children.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

Yeah, and that carries on. I don't think we'll ever really truly understand the impact that we have on people's lives. Because sometimes the smallest thing can have such a huge impact. And you never know what the consequence of that impact is going to be and how it's going to get carried on and facilitated.

It's like a little rip. And sometimes the smallest little pebble can make the biggest waves. And those carry on and carry on. And I'm even seeing that with my children today. And it's something that's really beautiful and inspires a lot of hope moving forward.

Patrice Keet:

And that partly kept me going thinking that we had a positive impact on you in that almost two years that you were with us. Friends would say, "Yeah, she's gone and we see you suffering. But you did good things for her and maybe that will help her." And then you've since said, those were the only happy childhood memories that you had.

Melissa LaHommedieu:

I wouldn't have had the connection that I do to academia. I wouldn't have had a lot of the same values that I do today had I not been introduced to it. And there were other foster homes that I went to that were not bad homes. There was nothing wrong with those homes.

But they still weren't happy homes for me. And I think I got little kernels of that in the home with my parents, that there was some secret sauce there. You did have some secret sauce.

Patrice Keet:

And you let your guard down. You let yourself say to yourself somehow along in those moments, "This could be the happy family or this moment is happy, and that your loyalty to your biological family had its limit." You were able to maybe say, "This is a little bit better."

"This is better.” If we're getting off into another area here. But I think listeners can hear whether it's a teacher, how many of us say, "Oh, that teacher was the one who inspired me to do X, Y, and Z." Or some people say, "That was the only person who believed in me when I was young, that coach, that teacher." So, anyone who's paying attention and around children pay even more attention.

Guy Kawasaki:

Thank you to Patrice Keet and Melissa LaHommedieu for sharing their remarkable journeys, their wisdom and their resilience. They are truly sources of inspiration. Their intertwined narratives remind us of the power of connection, the strength of the human spirit, and the incredible ways in which our lives can intersect.

My thanks to Janice Manabe for making this episode happen. If she had not brought Patrice and Melissa to my attention, I would've never heard this great story. Further thanks to the remarkable people team, producer and drop-in queen Madisun Nuismer, Tessa Nuismer, Luis Magaña, Alexis Nishimura, Fallon Yates, and the incredible sound design team of Jeff Sieh and Shannon Hernandez.

Thanks also to MERGE4. Remember, they make the coolest socks. Enter the promo code “FRIENDOFGUY” to get a 30 percent discount. Until next week, mahalo and aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply