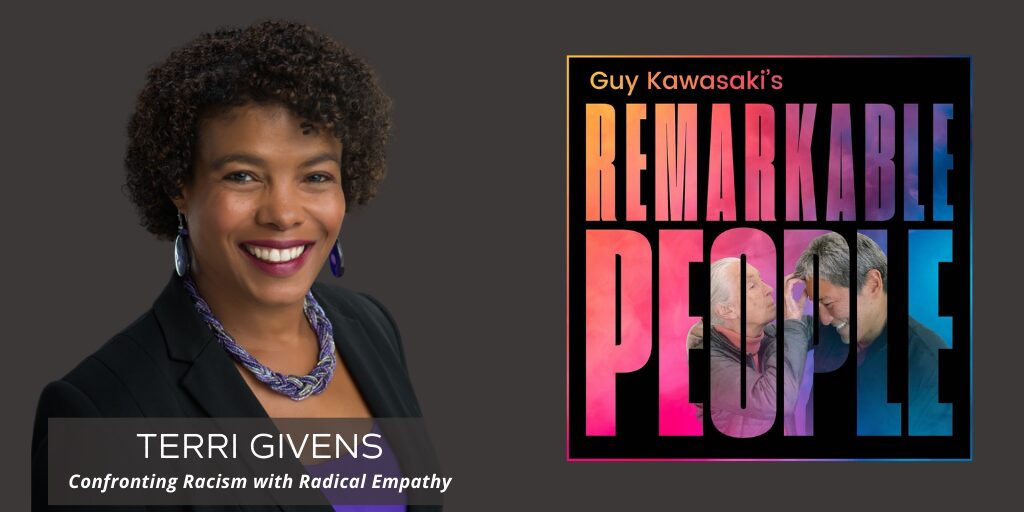

Welcome to Remarkable People. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Terri Givens, author of the groundbreaking book Radical Empathy.

Terri Givens is no ordinary academic; she is a trailblazer who has shattered barriers as the first African-American and first woman to serve as vice provost at the University of Texas at Austin and provost at Menlo College. Her dedication to fostering inclusive leadership in these troubled times shines through in her book, Radical Empathy.

In this episode, we dive into the complex issue of racism in America, exploring its historical roots and the reasons behind its persistence in modern society. Terri emphasizes the critical importance of understanding history to create meaningful change and shares her personal experiences navigating the challenges of systemic racism.

Please enjoy this remarkable episode, Terri Givens: Confronting Racism with Radical Empathy.

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Terri Givens: Confronting Racism with Radical Empathy.

Guy Kawasaki:

Hello everyone. I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People. We're on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Terri Givens. She's the former vice provost of the University of Texas at Austin and the former provost of Menlo College. Terri broke barriers as the first African American and first woman in both roles.

She has continued her journey at McGill University in Montreal, Canada. There she advises on anti-racist initiatives and contributes to academia through her professorship. Despite opportunities to ascend further in administrative ranks, Terri continues to make direct impact through her teaching of students.

In this episode, we dive into her new book, Radical Empathy. This reflects her dedication to fostering inclusive leadership in these very troubling times. I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People. And now, here is the remarkable Terri Givens. Would you start us off by explaining the roots of racism in America?

Terri Givens:

Yes, because that's a very important thing to understand, and this is why I wrote my book, The Roots of Racism, because I think we don't understand that history is still present today. And the roots of racism go back to the 1500s when you had Portuguese sailors first enslaving people in Africa. But the important thing about that is how they defined Africans at the time, which was they basically dehumanized them. And that dehumanization has persisted since then. So you see it in so many different ways.

And of course, to basically say that enslavement was okay, that the church was involved in defining who was human and who wasn't. And one of the important things we have to do is to trace the history. How did we get to where we are today?

As we know, people are trying to keep us from learning our history because they don't want people to understand those connections. They want to say, "Oh, we're done with racism. It doesn't matter." No, racism is baked into our systems, not just in the US but in Europe, across the globe. So we have to understand that history is critical to where we are today.

Guy Kawasaki:

I heard a theory from one of our other guests that, I don't know if it was 1600s or 1500s, but racism didn't really exist until somebody needed an intellectual argument for why we want to get free labor and enslave people. So in order to justify that, they came up with this theory that Black people are less than human, so it's okay to enslave them. What do you think of that theory?

Terri Givens:

I agree with it 100 percent. There's this really great book besides mine by Nell Painter called I'm going to forget the exact title, but it's how people became white and the history of white people basically. Because it's not just that we're saying Black people are not human, we're also saying white people are superior. So the underlying theme is that this whole history of white supremacy, and so you have to understand that component as well.

So yes, I agree with that. I said the Catholic Church was involved in saying it's okay to enslave Africans because they are not human. And so there's all these different factors. It really does go back to the 1500s when the church was involved in saying it's okay to enslave Africans.

Guy Kawasaki:

And why has something persisted for 500 years? You'd think we would figure out better ways to do business.

Terri Givens:

Well, you would think. But the reality is that we had this period of enslavement. We had the Civil War, which was to end slavery. But the federal government, after a few years of the whole process of theoretically moving us past slavery, just basically gave up eventually and let the south, and not just in the South, but they allowed the development of Jim Crow, voting laws, the disenfranchised Black people. I'm a researcher, this is what I do for a living.

And I'm actually working on a major project that is going to try to examine not just in the US, but why does this persist and what does race mean today? And so the bigger problem was in the United States and in other places that there was never a real acceptance of Black people.

You had all kinds of laws and regulations and rules that kept them from voting, that kept them from getting jobs. You can look in almost any developed country today, and Black people are going to be less employed. Let's take France, for example. This is a country that was a colonizer.

A lot of people who were in the colonies, like in Algeria have gone to France to find work. They get put into the suburbs because in France, the place where the poor people go is in the suburbs. So you've got Black people living in the suburbs. Their educational opportunities are less.

If you think about redlining, that happens everywhere. Redlining is the process where banks and regulators say, "Oh, we're going to make sure that people who live or buy these houses don't get preferred loans. They have to pay more," et cetera, et cetera.

And so there are so many different mechanisms that are put in place. That's why we call it systemic racism and systemic discrimination because you have the bureaucrats involved and they're doing these things consciously initially, and then they just get perpetuated over time.

Guy Kawasaki:

And do you think in this case that it's a racist argument, like, "We don't want Black people to have houses and competitive interest rates?" Or it's an intellectual argument that, "Oh, they're higher risk, so we have to charge them higher interest." Is it racism or flawed economics?

Terri Givens:

It's both. It's hard to separate out the two. I still have this issue today. I've been working on hiring more Black faculty at McGill University. And faculty will still come and say, "Why can't we just hire on merit?" We are hiring on merit. We're just saying that we want to recruit people who look different from you. And the funny thing is, we go around and we hire people from the best universities in the world, and then they're like, "Oh, I didn't know these people were out there.

Oh, let's go hire more." And it comes back to my other book, Radical Empathy, where people don't understand how they have internalized bias, how they have internalized these ideas about people. And they'll say, "Oh, we just hire on merit." But the only people you hire are your buddies who look just like you and you aren't willing to look at the people. We went to Stanford around the same time. No, actually I was ten years after you. So I'm a little younger.

Guy Kawasaki:

You're much younger.

Terri Givens:

I'm going to be sixty this year.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm going to be seventy.

Terri Givens:

Like I said, ten years apart. But even in that ten year difference, there were probably a few more Black students. But anyway, the interesting thing to me is that I was going to Stanford in the eighties and there were still a lot of issues around hiring Black faculty and they've gotten better. Don't get me wrong. I love my alma mater. But the problem is you look across academia and we're still only three or 4 percent of the faculty, and we're still struggling to hire and we're still struggling to retain.

And this whole idea of merit, we forget about the belonging component. And I know this is something you care deeply about and people should feel like they belong. So we hire these people, but we don't necessarily give them the opportunity to succeed in those positions.

Guy Kawasaki:

One of my frustrations with this is that how can you make decisions like this based on the color of skin? Tell me you made a decision on height or weight or color of pupil, but what's the rationale that someone with Black skin is somehow inferior to you and shouldn't get tenured? It makes absolutely no sense to me.

Terri Givens:

So this is the problem. We judge people, and I talk about it in the context of, "Okay, you have your tribal brain." You see somebody who looks different than you. And so your brain says, "Oh, this person isn't part of me." And so we have to fight against that tribal brain or that very basic idea that we only want to be around people who look like us.

But the reality is there's no one kind of Black person or Asian person. We all are a range of colors. And so basically in the 1800s and early 1900s, people just bent over backwards.

They wanted to look at things like skull size and all of that to try and say, "Oh, this group of people is inferior because their brains are smaller," kind of thing. So people have bent over backwards to try and find scientific reasons why people from Africa who have different skin color or people from Asia who are somehow inferior.

I could get into all kinds of trouble saying some of the things that people said about us, but it's a protectiveness. You see what is happening right now in places across the globe really, but particularly in the US, is people are trying to protect their privilege.

And so they ascribe a certain level of privilege to themselves if they're white. And then we don't want to let these other people have that same privilege because the problem is they see it as a pie. And if they get that, then I don't get that. Instead of saying, "We all get better if we all are open and accepting, all boats will rise." You need to talk to Heather McGee if you haven't yet, because her book is amazing, The Sum of Us.

Guy Kawasaki:

The problem is not to get a bigger slice of the pie. What you should do is bake a bigger pie. That's the solution.

Terri Givens:

Exactly.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm going to show you total naivety and ignorance. All right. But is there any example, in Africa, there's a Black nation and all the power structure was Black and they imported thousands of Europeans as slaves to work on plantations, and now it's 2024. And they're trying to wipe out their history of white enslavement and they're trying to preserve systemic racism against white people. Is there any country like that?

Terri Givens:

No, there's not.

Guy Kawasaki:

Not even Wakanda?

Terri Givens:

No. I wish Wakanda was there. Now the problem is you look at a place like South Africa or Zimbabwe, and they had white settlers. Once the governments were taken over by Black natives, South Africa has bent over backwards to support things for white people living there and their land and so on.

And Zimbabwe maybe not as much, but that's the only cases. There may be other African countries. One interesting case is Algeria, because Algeria, they didn't enslave. Nobody enslaved white people in Africa, as far as I know, maybe somewhere out there.

But Algeria was part of France until they got independence in the early sixties. And so once they got independence, a lot of the white French people left and moved back to France, and they felt like they had basically been expelled and they were unhappy. It's about that.

And that's why some of those people, their strongest supporters of the far right, National Front, which has now become the Rassemblement in France, but that's the closest I can come to is landowners. Once the country became independent, lost their land or had to leave and so on. So that's about the extent of it.

Guy Kawasaki:

I read your book about radical empathy and at the end, and this was in 2020, I would say you were fairly optimistic that things could get better. Now we're four years later, where's your mind at?

Terri Givens:

Very frustrated.

Guy Kawasaki:

Things have gotten worse.

Terri Givens:

In some places they've gotten worse. Yes. Not everywhere. And I'm always hopeful. It's my nature to be hopeful, and I'm actually working on a follow-up to Radical Empathy. And it's been hard to write because every day there's bad news.

But on the other hand, one of the goals of both Radical Empathy in the book I'm working on now is like you. I want to empower people. I want people to feel like they can do something. And when I wrote Radical Empathy, when I would talk to people about it, that's the first thing that came, which is, what can I do?

And so I'm hoping that yes, things are bad, and actually one of the things I'm writing about right now is the difference between apathy and empathy. And apathy is you just sit back and you're just going to let things happen. Versus empathy and radical empathy, which as you know is taking action. And we did in 2020, so many of us rose up and said, "Yes, I'm going to vote. I'm going to vote for democracy." And I think that's going to happen. I'm crossing my fingers and hoping that's going to happen again.

And we don't have interference and all of that. But I think that I am frustrated, but also still hopeful. I read your book and I'm like, "Look at all these amazing people and these remarkable people and what they're doing." And you're doing the work to bring these people to the forefront so people can see what you can do. And that's exactly what I want to do as well. I want people to understand I haven't given up. I'm still working, I'm still fighting, I'm still doing what I can do in my part of the world.

Part of the problem is, and there's some great books that have come out talking about how Black activists in particular, we tend to get burnt out and so on, and that we have to take care of ourselves.

And I'm doing that, but I also know that I'm privileged. I'm in a unique position. I am in the process of changing the university system in Canada to be more open to Black people. That's huge. And I think it's really important that we understand that the things we are doing, even in our little space of the world, is creating change.

Guy Kawasaki:

Would you say that America, 2024, is it an apartheid?

Terri Givens:

Not yet. And the reason we're not really apartheid is because the attacks that are happening now are intersectional. It's not just on Black people. When you get rid of a DEI program, people forget. It's not just Black people who benefit from that. It's women, it's people with disabilities. It's LGBTQI. It's everybody who is underrepresented or oppressed. And if it's an apartheid, it's an apartheid of white men versus everybody else. Because you can't say that, "Oh, we're getting rid of DEI."

And people want to say, "We're only going after this group." No, there's lots of research that shows one of the biggest beneficiaries of the civil rights acts and so on are women, all women. Women were able to get into the workforce, et cetera, et cetera. You're saying over 50 percent of the population is falling under the system of apartheid, I just think that there is resistance. No, we're not anywhere near that.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm going to tap all your political science expertise. Would you draw any similarities between America today and 1930 pre-Nazi Germany or pre-Nelson Mandela, South Africa? Are we South Africa or are we Nazi Germany? Are we headed in those directions?

Terri Givens:

Not yet is my answer. And even I've thought about this. Are we in Weimar, Germany? And I'm worried, but it's a different thing. So I'm a huge advocate of understanding history. But on the other hand, we also have to understand the complexity of our current age. And frankly, what really worries me is the inequality, that you have these billionaires out there who are controlling the media and so on.

And are trying to push certain types of agendas that is influencing people to vote particular ways and act particular ways. And that is different in the sense that I don't see the US going out and starting wars. And I think I see the US, if we go in that particular direction, becoming more insular, but we're in a very much a global environment.

And so I think when people in Europe, for example, have seen what's happening, in that Germany, they have a far right party, and there have been millions of people on the streets saying, "No, we don't want this far right party to be in our government."

And there are millions of Americans. The funny thing is, actually, it's not funny, it's sad, is there are protests and things going on in the US on a daily basis, and the media is not covering it. They're happy to cover, "We're going to go talk to this Trump voter," but they won't talk to the thousands of people who are protesting in front of the Supreme Court about their latest ruling.

And there's a lot of things happening. I have friends who are out there writing postcards to get people to vote. I have friends who are working with candidates all over the place.

Here in Canada, there's huge groups of people who are fighting for democracy on various fronts. And so I think that democracy is in danger around the globe, but I'm still hopeful that there's enough of us who are supporting. We both have lived in California. I always tell people I'm in Vancouver, British Columbia right now, but I think that the whole West Coast, if it gets to that point, we'll split away and we'll have California and Oregon, and Washington.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm up for that. That works for me. Gavin Newsom for president of our country. I could live with that. So in your book, you said several times, and it was certainly a surprise, but almost a shock. And listen, I'm an Asian-American male, so I don't walk in your shoes, but you say that racism manifests itself daily in your reality. So can you tell me how racism manifests itself daily in someone as successful and visible and powerful and et cetera, et cetera, as you.

We're not talking about some illegal immigrant who's working in the back of a restaurant, we're talking about Terri Givens, my God. So how does racism affect your daily reality?

Terri Givens:

Well, not everybody knows who Terri Givens is. They will eventually, especially after this podcast. They will.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's right.

Terri Givens:

But it's really interesting because part of it is internalized. So my reality is yesterday I was walking around and I was like, "Oh, I'm going to go into this boutique." Every time I walk into a place where people do not know who I am, I'm like, "Okay, how am I dressed? Are they watching me? I have to put a smile on my face. I try to be non-threatening."

And so that's not that the people in the store, I don't know if they're racist or not. And throughout my career, because I've been a trendsetter and ahead of my time in so many ways in political science.

I've been in high level positions. And the reality is that I'm often the only Black person in the room or the only woman in the room. And there's so many different ways that the racism manifests itself. And it's not just the fact that people see I'm a Black woman and might be racist towards me. It's just the things I study. I study race and immigration politics in Europe, and I can't tell you how many times people have said, "Oh, why do you study Europe?" They're so surprised when I tell them I speak French and German.

And the funny thing is, this could happen to anybody, but I could be a white guy as an American, "Why do you study French and German and so on" but they aren't going to be as surprised.

Guy Kawasaki:

I can honestly say Terri, that I have never met a white man who had imposter syndrome.

Terri Givens:

Yes. What's really funny, I'm on a job search right now for an executive director of an organization, and I was laughing because we didn't get very many women and minorities applying, but we had a lot of white men. And I was laughing because I was like, "These white guys aren't even qualified for this position, but they apply."

Whereas we know, research shows women and minorities won't apply for positions that they think they don't qualify for. But these white guys are like, "Oh yeah, I qualify. I'm going to go ahead." And we didn't keep them in the pool. The audacity.

Guy Kawasaki:

I don't know. So let me ask you something. So what's the end goal? To use your terminology so people don't get all pissed off with me when I ask this question, but is the end game for every Negro to be an exceptional Negro is that the goal?

Terri Givens:

No, absolutely not. The goal is for every person, for everybody to be who they are. So this was a struggle I went through personally is how do I make sense of who I am and so on and so forth. I'm Black. People would give me a hard time for the way I talked because I didn't talk Black, blah, blah, blah, this and that. The reality is people try to put you into boxes. So what I want for everyone, not just Black people, but for everyone just to not have to live in the box and to be who you are.

By the time I got to the end of my twenties, early thirties, I finally figured out just be who you are and don't be afraid to be who you are. It's not even racism. It's expectations. "Terri Givens is a graduate student at UCLA. Oh, she must be studying race and ethnic politics in the United States." I literally had people say, "I would give you a job if you studied race and politics in the U.S." That's not what I study.

And I don't want your job if that's what your expectation is. And that's why I'm like, "First of all, start with yourself. Who are you? And do you really want people putting you into boxes the way that you're doing to others?" Not everybody's going to be exceptional. We just want people to be able to have access to becoming remarkable, and that's what we're doing here. But also just being who you are.

Guy Kawasaki:

When the term in your book was used as exceptional Negro, it wasn't about getting the best scores or anything like that. It was basically fulfilling a white man's expectation of what a Black person should be. If you did that, you were "an exceptional Negro." Right?

Terri Givens:

And I was applying that to myself because the problem is people look at me and say, "Oh, you're exceptional, and Oprah's exceptional, and Chris Rock is exceptional, but the rest of those Black people, we don't care about them." And so this is the problem. We can pick out a few people, and they are exceptions. So that word exception is important. They're the exception to the rule.

And the rule is that Black people aren't to the level that we think white people are, "But you're okay." I remember when it was a big deal that Barack Obama was articulate. It's like, "Well, yeah, he speaks normal English. What's wrong with him?"

Guy Kawasaki:

And he smokes.

Terri Givens:

Yes. That's a whole other story.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, purely in practical terms, are you serious? Are you saying that a white male can possibly empathize with a Black woman?

Terri Givens:

I have had so many white males who have been the ones who have propelled me along my career. Yes, absolutely. Going back to high school, I remember my high school principal who was a Jesuit priest, stopped me in the hall one day. I'd recently taken the PSAT, and he was like, "Terri, are you going to apply to Harvard or Yale or Princeton?" I'm like, "What are you talking about? I'm first gen. I don't even know what college is."

And he saw me. It's not just empathy, it's actually being seen. And there are many white men who I can tell you have seen me. They accepted me as a Black woman who speaks French and studies European politics and can be a leader. And I always say there are people who saw more in me than I saw in myself. And those were mostly white men.

Guy Kawasaki:

Really?

Terri Givens:

Absolutely. 100 percent.

Guy Kawasaki:

Terri, they were exceptional white men.

Terri Givens:

You got me.

Guy Kawasaki:

So now you talk about just the beauty of empathy and even beyond that radical empathy. But are you saying conceptually that you should have radical empathy for the Trumps? Is there a limit to empathy?

Terri Givens:

The number one thing, and that's going to be the very top of the first chapter of my next book, is empathy is not absolution. I do say this in the book. Look, not everybody's going to listen to me or hear my message. I don't need all these people who support Trump to understand or have empathy.

But there's this huge number of people out there who are open and want a better world and want to understand these things. And I can tell you, I've had many interesting discussions about this over the last few years in particular.

And there's some people you can't reach. Not everybody's going to be remarkable, but what we need is that core group of people because we can move mountains. And that's the thing we have to understand is that I may not be able to convince this Trump voter over here, but maybe I can convince this independent person over here, and then they're eventually going to talk to their buddy who's a Trumper.

It's a process, and the process is working right now so that these people are cut off and they only watch certain media. But if we can start to break through those silos, not directly necessarily, but really get the word out so that people understand that there's a different way to think about them.

Guy Kawasaki:

You also expressed something, which when I read that, I said, how do these two things relate to each other? And you made a statement that empathy requires embracing vulnerability. So why does being empathetic require being vulnerable?

Terri Givens:

Thank you for that question, because that's one of my favorite things about radical empathy, and you'll see I'm vulnerable all the way through the book. I try to model vulnerability. But what I figured out in my own life, and I've seen this in other people, you mentioned imposter syndrome. So part of the problem for me personally was that I had a hard time accepting who I am. And it was partly because I didn't really understand who I was. And I grew up in Spokane, Washington. It's less than 1 percent Black.

And I'm just like, why did my parents choose for us to grow up in Spokane, Washington of all places? But as I learned that history and about the great Migration and how Black people from my parents' era wanted better than what they had experienced.

And so by moving to the Northwest, my dad was in the military, Spokane was the last place he was stationed, so it made sense for us to just stay there. It was where he grew up outside of Pittsburgh. I went there and visited, "Oh, no wonder he settled in Spokane. It's a lot like where he grew up." But a big part of that is that they wanted us to have better education, to be safe, et cetera.

So for them, Spokane was that place, but I didn't grow up around a lot of other Black people. And so that was something that I would beat myself up about. I wasn't in the same social situations as a lot of my friends when I went to Stanford, et cetera, et cetera. But what I had to learn was I had to be vulnerable to be willing to look at those stories, that history, to try to understand. So the first step in vulnerability was saying, "I need to understand better why my parents made these choices, why I am who I am."

Because I had some anger towards my parents. And so by being vulnerable, and it's hard to ask yourself those tough questions if you're not vulnerable. And Brené Brown, she's my model when I talk about vulnerability.

But the biggest thing about vulnerability, first of all, we can talk about it in the context of leadership, but it's really important to be vulnerable with yourself because people always say, "Why do I have to be vulnerable?" It's not with everybody else. You have to be vulnerable with yourself so that you understand yourself better so that you know who you are so that you're more open to other people.

It's really hard to love others if you don't love yourself. So you have to be vulnerable and look at the full picture and try to understand why you are the way you are and say, "I'm okay with that." That makes it much more likely that you're going to be okay with other people because you see yourself and then you can see others

Guy Kawasaki:

Explain to me. Well, that implies that I don't agree or I don't understand, which is not true. But why do we need to teach the history of slavery in America?

Terri Givens:

Yes, that's a great question. Because it still has implications today. So we had 400 years of enslavement, and we haven't been how many years since 1860s. Historically, we're still not that far away from it. And because you can't understand why we had Jim Crow, if you didn't understand slavery.

You can't understand why the US shut itself off to immigration except from Northern and Western Europe if you didn't understand the history of slavery. Because it was all part of a process where even though we ended enslavement, we still had the same ideas about people.

And that's why it's really important to understand that it wasn't just about slavery, it was about a worldview that said certain people are not human or certain people are lesser than. And that included people from Southern and Eastern Europe. That's why in the 1920s, the US cut off immigration from Southern and Eastern Europe and most of the rest of the world. People don't really know that we cut off immigration for most parts of the world except for Europe from the 1920s till the 1960s.

And after that is when you start to see more people coming from India. The first group of people to have immigration control placed on them were Chinese. You had Chinese exclusion in the 1870s. And so it's not just that there was enslavement, there was a whole worldview of white supremacy that said, "We don't want Chinese."

They couldn't get rid of the Black people. There were too many of us. So they were going to put all kinds of rules and regulations, and for Jim Crow laws about you have to sit in the back of the bus. And you can't go to good schools, et cetera. It's still impacting things. When I got to McGill University in 2021, there were twelve Black faculty out of 1,700.

Guy Kawasaki:

What?

Terri Givens:

Now why is that?

Guy Kawasaki:

Twelve out of 1,700?

Terri Givens:

Yes. Not because of me and many others who did a lot of work were close to fifty, and it's like Canada didn't go through slavery. And they did, but it wasn't like in the U.S. So why does this happen? Because people have ideas. Those ideas don't come from nowhere. Those ideas come from 400 years of enslavement, Jim Crow, Chinese exclusion, exclusion of people from Southern and Eastern Europe, Irish people being considered Black, all kinds of things.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. I'll tell you this story as an aside. I have hosted many AI panels, members of the panel, including chancellors of very large schools. And unlike most AI moderators, I always ask this question, which is, who would you rather have designed your kids' curriculum? Ron DeSantis or ChatGPT? Everybody says ChatGPT. I will tell you that I have gone to ChatGPT and asked why should we teach the history of slavery in America?

And ChatGPT comes up with six great bullet points about the benefits of teaching slavery in America. And I tell you that story only because I think ChatGPT is smarter than Ron DeSantis, but that's not a very high bar.

Terri Givens:

So AI is a learning model. It's pulling in information, and it's not biased in any way about that information. It's saying, "Look, here's what I have learned. I'm going to give it back to you." And so it has this material that is saying these things about why we need to understand this history.

So that doesn't surprise me. And frankly, there's so much research and I have colleagues all over who do this work. And what's really interesting is, forget DeSantis and all that. The people who matter are students, what are they learning?

I taught class a year ago. I love my students. It was just such a blessing. Even my students from Sweden, McGill is a very international university. So I had students from all over, and it was probably one of the most diverse classrooms I have ever taught.

Eighty students and a little bit of everything. And I tried to really create a classroom where everybody could say what they want, that they wouldn't have any fear. And so many students told their stories because I would tell my stories. So they would tell me their stories about their parents who were immigrants, the difficulties they had wearing the hijab, all kinds of things.

And the Canadian students coming to me and saying, "I never knew that Canada excluded Chinese people and had slavery and all these things." And so to me, that is just so gratifying that I have the privilege of being able to teach these students these things. And they're grateful. DeSantis acknowledged, "Oh, we're making white people feel bad."

No, we're not. We're helping them learn and understand their history. They don't understand why there's so many Black people living in horrible living conditions in the United States.

Why do we have homeless people living on the streets? All these things. They need to understand that because they want to create change. They have the energy, they're out there. So many students who've gone into activism and working in non-profits, and I think people like DeSantis are afraid they're going to overthrow this white supremacy, white male.

And I got to remind myself, I always have to remember to say white male supremacy because white women are being oppressed as well, but they want this change. Our students are the ones who are pushing for diversity and understanding.

Guy Kawasaki:

When you say that, isn't that the reason that school boards and stuff are trying to remove. Not to be too clever, but they're basically trying to whitewash history?

Terri Givens:

Yes, absolutely. Because they're afraid. But the funny thing is, these kids are getting this news. My boys are older, but we don't control what they read. And my boys are out there doing stuff that I'm just surprised they know more about so many things than I do because they are consumers of what's out there. And of course they follow what their mom does and so on, but they have chosen the things that they really care about.

The environment is a really big thing for them. And the funny thing is, the more you try to hold tight, the easier it is that things are going to slip away. And that's what they don't understand when they're trying to ban books. And it just makes kids curious, "Oh, this book is banned. Ooh, I'm going to read it."

Guy Kawasaki:

I'll tell you that this is another aside, but I hope that Think Remarkable is banned in Florida and Texas.

Terri Givens:

I know I keep waiting for Radical Empathy.

Guy Kawasaki:

There should be some service that submit your book to Ron DeSantis and Greg Abbott.

Terri Givens:

Absolutely. Roots of Racism, which is the politics of white supremacy in the US and Europe. That's at the top of the list.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh my God, that and The Project 1619, those definitely two books. I open up Think Remarkable with a discussion of Olivia Juliana because I'm hoping that some legislator reads this in Florida, in Texas, this is, holy shit. He opened up with the most radical Latina we know, and we got to ban this book, but it hasn't worked yet. If I figure out how to get my book ban, you'll be the first to know, Terri Givens. I guarantee you.

Terri Givens:

Thank you so much, Guy Kawasaki.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm always speaking about you. How do we bridge the racial divide? That's an easy question. Go ahead. I'll give you sixty seconds.

Terri Givens:

Let's see. How do we bridge the racial divide in sixty seconds? First of all, we have to recognize it. And so the first step is it's like that whole thing of vulnerability and internalizing.

And that's the other reason you have to be vulnerable because you aren't willing to recognize that there is a racial divide unless you're willing to be vulnerable and say, "Yes, I have internalized bias." That's a really important component. And I think we can bridge racial divides if we all understand that we all have bias and that we need to work past it.

And sorry I'm going past sixty seconds, but I have so many friends who are, yes, Black Lives Matter, blah, blah, blah, but they don't understand. I have a house in Menlo Park. We have to be willing to have more than just me and my friend who are Black living in Menlo Park.

And we have to figure out, what do we do to get there? And that takes action. And how do we make people who aren't currently living there to feel like they belong? So anyway, that's more than sixty seconds, but the most important part is recognizing the problem.

Guy Kawasaki:

All right, let's suppose that you have recognized a problem and you're not a provost or you're not in charge of a university, you're just, I don't know, your random Google or Apple employee or whoever the demographics are that listen to my podcast. And now you believe and you understand, and your question is, what can I do? What's the answer?

Terri Givens:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'll give you 120 seconds for this.

Terri Givens:

Thank you. Like I said, so first step, figure out where you are and what you have the capacity for. So some people, they are good at writing, so write your congressman. Some people are good at hosting friends, have dinner parties and talk to your friends about the issues. I think you talk about this in your book too, find what are you passionate about? What do you care about?

I joined the Peninsula Clean Energy Commission because of their Citizens Council, because I care about the environment. I support lots of nonprofits. I'm so proud of this organization, Foundation for a College Education. I was the board director for several years and they just got a two million dollar grant from MacKenzie Scott.

Guy Kawasaki:

MacKenzie Scott.

Terri Givens:

And MacKenzie Scott. Yes. And trust me, there were times when I didn't think that organization was going to survive, and now they're just blossoming. And I didn't know three years ago that this organization was going to do so well, but they did. And I can say I was a part of that.

And I can look back at every place I've been, and I've done something at every one of those places to create change. And it can be small. You can just convince one other person to vote. Or it can be big if you have the money, you can support a candidate you believe in or you can help an organization.

And I support lots of organizations. I've been on ten different nonprofit boards. Some of us do too much, but it's who I am. I always do too much. But the reality is don't feel overwhelmed. Do something that is within your capacity and then build on that. And eventually you'll get to that place where you're as remarkable as me and Guy.

Guy Kawasaki:

You should aim higher than trying to be as remarkable as me. Aim higher for Jane Goodall and Terri Givens. So that was Terri Givens. I hope you have a greater understanding of racism in America and what we need to end that problem. Check out her book Radical Empathy. It's sure to help you be a better person. My name is Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People.

May I just remind you that Madisun Nuismer and I, we have a new book out called Think Remarkable. We take the inspiration and information we gain from conducting over 200 interviews and make it into a very brief book.

Think of it as a guide to life, a guide to how to make a difference, and how to be remarkable. Anyway, now let's just thank the rest of the Remarkable People team. Well, you already heard Madisun Nuismer. She's not only my co-author, she's also the producer of the Remarkable People Podcast. Tessa Nuismer is our researcher. Alexis Nishimura and Luis Magaña are also on the Remarkable People Team.

And last but certainly not least, are our amazing sound design engineers. That would be Jeff Sieh and Shannon Hernandez. We are the Remarkable People team, and we are on a mission to make you remarkable. Until next time, Mahalo and Aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply