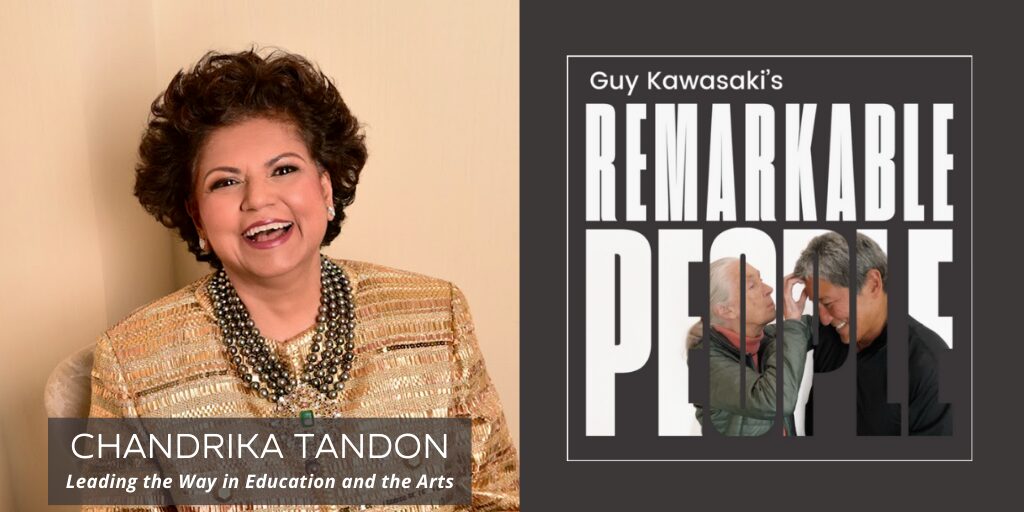

Welcome to Remarkable People. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Chandrika Tandon, a multifaceted leader, humanitarian, and Grammy-nominated musician.

Chandrika’s mission is to elevate economic and emotional well-being through education and the arts. Her work in higher education, especially in STEM fields, has been nothing short of transformative. She chairs the Board of the NYU Tandon School of Engineering, which has experienced remarkable success under her guidance.

But Chandrika’s influence extends far beyond academia. She’s a Trustee of New York University, a dedicated advocate for the arts, and a Grammy-nominated artist with a soulful voice that has graced major venues worldwide.

Join us in this engaging conversation as we explore Chandrika Tandon’s journey and her commitment to creating a better world through education and the arts. Discover how one person’s passion and dedication can inspire us all.

Listen to the episode now and be inspired by Chandrika’s remarkable story.

P.S. Chandrika came out with a new album, Ammu’s Treasures. Check it out…it will blow your mind!

Please enjoy this remarkable episode, Chandrika Tandon: Leading the Way in Education and the Arts.

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Chandrika Tandon: Leading the Way in Education and the Arts

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People. The Remarkable People team and I, we're on a mission to make you remarkable. Our guest today is Chandrika Tandon. She is a business leader, humanitarian and Grammy-nominated musician. Her mission is to elevate economic and emotional wellbeing through education and the arts. Chandrika has been recognized for her leadership in higher education as the Chair of the Board of the NYU Tandon School of Engineering. She has overseen the school's steady climb in rankings, groundbreaking global research and enhanced access for first-generation and female students.

Yet Chandrika is not focused solely on economic wellbeing. Through her soulful music compositions, she aims to nurture emotional health as well. Chandrika has produced several albums, performed in venues worldwide and in 2019 was nominated for a Grammy Award. Her latest album is entitled Ammu's Treasures and celebrates intergenerational love through a rich fusion of styles.

With experience in leading firms such as McKinsey & Company, Chandrika has an impressive professional background, but it is her humanitarian spirit and creative passion that truly set her apart. Chandrika endeavors to lift up people in communities across the globe. I can't wait for you to meet her. I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People and now here is the remarkable Chandrika Tandon.

You were a partner at McKinsey, Wall Street financial mogul, Grammy-nominated musician, NYU Business School named after you, and then your sister, CEO of Pepsi. And then you have this brilliant brother. I'm seeing a pattern here. Was it the environment or was it the DNA in your family?

Chandrika Tandon:

The waters of Chennai (Madras), India.

Guy Kawasaki:

Where can I buy some?

Chandrika Tandon:

We grew up with a grandfather and I was the oldest and we were in a very small town, Guy, in Chennai, Madras, it's called now. And we had no internet. Our walls were very tiny and our world was very tiny, but the way the windows and doors were open to me was through books. So at the tender age of ten, I was reading Thackeray and I was reading the multiple plays of Shakespeare, thirty-seven to be exact. I knew by memory about 200 poems from Daffodils to Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard.

So my world inside was very vast. From an ambition perspective, I was never going to be limited because however limited it was the world of books. And the other side of it is my mother was always playing music in the house and we only had two radio stations in Madras at that time. And those two radio stations started playing music at 5:00 AM or something like that and they would finish at 11:00 PM. And those two radio stations were on in different rooms all the time. So you didn't have a choice to pick, "Oh, let me listen to jazz right now."

Guy Kawasaki:

Tell me about your grandfather because I catch this thread that your grandfather was very influential?

Chandrika Tandon:

Yes. We lived in his house, we lived with him. My mother was taking care of him because my father would be traveling all the time and my father was the main son of the family. So my day began with my grandfather and my evenings and night ended with my grandfather. He was ninety-two when he died, and he was the most special person in my life. So he would work with us, he would study with us, he would learn any hobby that I got engaged with, whether it was chess or whether it was Scrabble or whatever interests I had, he developed, crossword puzzles.

It was an incredible, loving figure to have in my life. And because my grandfather was a judge, he opened all kinds of doors to me that I never thought existed, that I could never have envisioned in my little town of Madras with this very cloistered life that I was living. But I saw the world, I saw Cornwall through the eyes of Thackeray and I saw England through the eyes of every British author. So that's what happened in my life.

Guy Kawasaki:

One thread of thought here is that anybody listening should understand how much they can influence their children and grandchildren by broadening their horizons, right?

Chandrika Tandon:

This awareness is so raw and it's so big and so visceral in my consciousness, Guy, because what my grandfather did with me has stuck with me so many years later consciously and unconsciously and has changed the course of my life. And in a lot of ways I've got grandchildren now and I've been spending a lot of time with them whenever I can.

But trying to use that time very focused on sharing with them what it is that I can, whatever it is. But in my case, it was songs, it's nostalgia through songs, it's messages through songs. That's one avenue I've chosen. But I think we all have so much intergenerational wisdom and love and nostalgia and memories and experiences to share, which are going to have ripple effects for generations.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. Your story is remarkable. Going from Chennai to Citibank to McKinsey to New York to Grammy to philanthropy. Can you give us the gist of how that journey played out?

Chandrika Tandon:

In a very high level way, I was lucky enough to go on a hunger strike and be able to go to a great college and do a bachelor's degree in commerce or in business. And then to really fight to go to business school, the top business school in India. And then the journey continued over the years. I had a very singular business career for a long time. I say singular because my mind was focused on business.

Even though I love music, I loved a lot of other things, I would always be working, maybe even part of my forties. I never saw the light of day, I just worked hard. I worked really hard. But what I would do, Guy, because I love music so much, I'd be all over the world traveling for business but at ten o'clock at night, I would finish my client work and I would try to go to a piano bar, not try to, most nights I would go to wherever music was.

So that's where I heard the great Brazilian musicians like Caetano Veloso or Gilberto Gil or a lot of those great people when I was living in Brazil and in France and Australia. Wherever in the world I was, I would seek out music, but business was my main focus. But that went on and about twenty some years ago, I had a, the best way to describe it is a crisis of spirit because I had to ask myself the question, what am I trying to do? What is my point? What is enough? How much success? What is success? What do I want to keep doing?

And I'm so lucky that I got to ask those questions, Guy, because that changed the trajectory of my life. That's when I really started to focus intentionally on this answer, which is my joy, my happiest moments had something to do with music, always something to do with music.

I loved my business world, but I really was me when I was doing my music. And it wasn't because I was trying to get anywhere. I wasn't trying to win awards, it wasn't what it was about. I just loved singing. I loved learning and I loved sharing the music with people. And the second thing I made a decision about is that I would also spend a life doing something which had purity of purpose, that I would spend time serving, whatever in a small way.

It could be a random act of kindness or just something which is bigger than myself. Because we get so wrapped up in thinking about me, so I made a decision to step away from myself. And that's what began this incredible journey, Guy, where I went from a singular, single dimensional, business focused person into really building the music side and really building the service side, which is how NYU came into the picture.

And at that time, I found the dean of the business school and said to him, "Can I help in some way? I'm not looking for anything. I just want to help." And he said, "Oh, come on in. Please come in." Become what they call an Executives in Residence. Of course, I had a lot of years of business experience. And I started to teach classes, I started to work with the dean on different things for the school.

And that's how my whole association with NYU began till we gave a major gift for the engineering school. And for the music side, this is what happened, but again, by accident. So it wasn't that I was setting out to be anything. My promise twenty-two years ago was I would live a very authentic life, a life which really focused on clarity on what happiness was to me and a life that I would share whatever I had with other people, in whatever degree I can and that I wouldn't beat myself up.

And this is an important part I want to touch on because until then, so much of me was wearing this badge of I'm a perfectionist with great honor. I was always going to do better, I wasn't good enough and I wanted to do more. And oh goodness, did I not do enough of this? I wasn't a good enough wife, a good enough mother, good enough this, good enough that. I just started to drop all that.

I went from, I'm a perfectionist to I am perfection at this moment but let me live intentionally. Let me live authentically. So that has become the mantra. Am I 100 percent every day doing that? No, but I'm a lot more clear and intentional about it than I have ever been. And each year, each month, each day it gets easier. It's much more unconscious. It was in 1999, that's twenty-four years ago. I’m sixty-eight now, so going to be sixty-nine soon.

Guy Kawasaki:

We're the same age.

Chandrika Tandon:

Oh, we are? Wonderful. Yep. It was about twenty-four years ago.

Guy Kawasaki:

You said something in your answer that I need you to explain because I don't mean to make this into a joke, but when somebody from India says, I went on a hunger strike, it has a lot more meaning than a random person. And you said you went on a hunger strike to get your education. Can you explain that? Because I don't think you meant it in the Gandhi sense.

Chandrika Tandon:

In my own little way, it was pretty Gandhian because I did go without food for, it was two days, which was a lot for, the first time I was fourteen when I did it. Because my mother wouldn't let me go to a college, which I wanted to go to study business. Because the college was about an hour away and it was mostly men, and she wasn't going to have any of that.

And this was the only college open for women to study business at that time. It was a top college, it was a very prestigious program and I got in. And she wouldn't let me and I was determined that I was not going to be stopped. And so I did in fact stop eating. It was pretty Gandhian because she's a tough woman and I had never quite fought her before in such a profound way.

Guy Kawasaki:

And what did grandpa say when this was happening?

Chandrika Tandon:

Grandpa just would look very sadly at me because I was the love of his life and he would basically go to my mother and say, "Let her do whatever she wants." But what my grandpa gave me the courage to do, which is the most wonderful thing that happened, is he told me, "Why don't you ask your headmistress in school to help you?" Because I was crying so much. And so I went to school because I was still in school at that time. I went to school and spoke to my headmistress, who was from the Franciscan Missionaries of Mary, Sister Mary Nessen, and she was in a white habit.

And I'll tell you, Guy, I had been in that school from whatever, pre-kindergarten until 11th grade at that time, I had never seen her outside the school premises. For the first time in my life, she came to my little street, wearing her white habit in a black car. She came in to meet my mother, which the whole street was standing outside to watch this nun walk in. And then she said, "Mrs. Krishnamurthy, your daughter will be fine. You have to let her go." She was an Irish nun. And ultimately, I think that's how my mother relented.

So for the second time I went on a hunger strike, which was to go to business school, I was a pro at that. So my mom and I by now had our negotiating strategies worked out. She knew I wasn't going to give up and I knew I was going to win. But then this time, I straightaway went to the head of my school at college where I'd just finished my business degree and he came straightaway with a whole army of people to tell my mother she had to let me go to business school, but this time I had to leave home completely.

Which I understand how difficult it was for her to let her firstborn daughter who was supposed to uphold the family honor, here I was going off into a den of men, in the first case, and then I was going to be away from home, outside of her control the second time. And so I understand her angst, what was I going to do? How was I going to behave? Was I going to be respectable when I came back?

Guy Kawasaki:

I almost fell off the chair there.

Chandrika Tandon:

But now I get it, but at that time, I was single-minded in my pursuit. I was going to business school. Plus a thing I better tell you, Guy, is an uncle of mine. The reason I even applied to business school was an uncle of mine and I told him, "I want apply to this business school." It was a lark because my professor told me I should apply. He said, "Oh, you'll never get in. It's like a Nobel Prize. You're just a three-year degree because most people who get in are much more experienced. You're never going to get in."

That time I was going to get in or at least I was going to try hard. And since I got in, there was no way my mom or anyone was going to stop me. So it was like a wonderful fight. And really, I must say, even though I talk about this, I really honor the fact that my mother, hunger strike or no hunger strike, she could have still put her foot down and said no and I wouldn't have done it. I really have to hand it to her that she let me go finally.

Guy Kawasaki:

Is she still alive?

Chandrika Tandon:

Ninety-two and in great health and very lucid and will now tell you that she was the greatest proponent of my doing all these things.

Guy Kawasaki:

Is she in Chennai?

Chandrika Tandon:

She's in New York. Right nearby.

Guy Kawasaki:

Maybe I should interview her.

Chandrika Tandon:

She will tell you that she's so proud of everything we have done now.

Guy Kawasaki:

The entire arc of your life could have changed if she went on a hunger strike and said, "If you went to these schools, I'm not going to eat."

Chandrika Tandon:

It was something like that. Our fights were epic. My mother and my fights were epic. Because see, my sister had it easy because she was a year behind, so there were no fights in her case, I'd already done all the fighting, to go to business school, to go to college. And she followed me to the exact same college without nary a protest and business school, forget it. As I proudly think to myself, this is the path of whoever tries to pioneer something that's off the beaten track.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah. Dare I ask, what are your family reunions like? Is Indra bringing cases of Pepsi and you're bringing your musicals and your brother, it must be a hell of a reunion?

Chandrika Tandon:

Music was always part of how we all interacted with each other. India would have a lot of power cuts and load shedding, when the whole house would be plunged into darkness. So there wasn't anything else you could do so our family would get together and sing. So we would all sing songs together and the second thing we would do is make jokes. And we had a lot of uncles and aunts. My mother's one of a big family, my father's one of a big family and everybody would be just sitting there telling jokes, just happy family jokes.

So I'd say most of our family reunions are around a lot of jokes and now our children are all into music and so on. So I just think music and jokes are always part of how we interacted. Though I would say, as life has gotten a lot busier, Guy, it's that much harder to find time for real family reunions all the time because we've all gone in different directions. And interestingly enough, all of us came independent of each other.

This wasn't the chain migration here. Each of us came on independent paths for independent accomplishments or independent pursuits rather, we came in for. I came to McKinsey, my sister came here to do a business degree, my brother came here to go to Yale for his undergraduate. So all of us came completely on our own paths.

Guy Kawasaki:

Not exactly like that, all moving to Florida?

Chandrika Tandon:

No, we love Florida for certain parts of the winter, but I came into New York City in 1979 and I literally love the city so much. I've been here forever and wherever I go, and I go to many places because most of my work has been outside and all over the world, New York is home to me. This is the longest I've lived anywhere and I love the city. I'm very involved in different parts of the city, the universities, the cultural events.

And the wonderful thing here, Guy, is that New York City is many countries in one. We talk of melting pots, but there are so many epicenters because whatever your interests are, you can find your epicenter. If you like music, you can find it. If you like Brazilian music, some of the best Brazilian singers I've heard are in New York. In fact, Astrud Gilberto would be here and I would book tickets three nights in a row if she was performing.

And the same thing when you had French singers or a Stan Getz or any great person, Joan Baez, I've heard all of them in New York. The greatest Indian singers, in fact, the early years, many of them would come and stay with me because you have greater access to the cultural scene. So I just feel blessed and privileged to be here and to be able to partake of the city. And the other thing, being part of a university in whatever way allows me to connect with the research, the students, the young thoughts, the brilliant minds in areas I'm not that familiar with. So it's been like a continuous education over the last twenty years.

Guy Kawasaki:

I bet that people listening to this are wondering, how do I know when it's time to make a big career shift? And in particular, how do I know when it's a false flag, when I should not shift and I should stick it out? Because two conflicting bodies of thought, that you stick it out and you grid it out and you gut it out. Then the other is to make these transitions like you did. So how do you know when the time is right?

Chandrika Tandon:

This is a really great question, Guy. So I don't think it's about the time. I think it's about having the time to reflect on what it is that drives your happiness and your passion. If you're someone who loves to connect with people through podcasts, it doesn't matter what the age is. You owe it to yourself to find the time to do that, whatever your other job may or may not be. Over a period of time perhaps this will transition into a full job, maybe it won't, but you're not doing this because you want another job, because you want to transition.

I went to music because I felt my soul would collapse, my whole being would shrink and it was shrinking, without it having a center space in my life. It wasn't that I gave up everything and moved to a musical refuge and started singing for the next several years. No, it was an incredible struggle for me. Because I had for a period of time to think about how to balance my business life, I was still a mother, I was still a wife, I still had all kinds of responsibilities.

I still had a company to run, and I wanted to fit in music. And this is why I've told other people before, I would get up on Saturdays at 4:00 AM in the morning, every Saturday, and I would work intense schedules during the week. 4:00 AM to 6:00 AM, I would drive for two hours to Wesleyan, have a class from 6:00 AM to 8:00 AM and then drive back again and be back by 10:00 AM, 10:15 AM because my little baby would wake up, she'd be waking up by about 11:00 AM. Thank goodness she was a late riser.

And it's fine on a day to do that but try doing it when you're scraping ice off your car in the middle of winter and you're not even sure how icy the roads are at 4:30 in the morning. And I wasn't a particularly adventurous driver, so these used to be terrifying moments. So sometimes I would leave at 3:15 just AM so I could drive slowly, but I was going to get to my class. So it required a lot of adjustments in my life. And working with NYU in the early years and even now to some degree, Guy, nobody even knew I was doing it.

I was doing it for myself. I wasn't doing it because I wanted fame or fortune. I would spend hours at the school, I would spend hours with the students, not because anyone cared, but because I felt this is what I should be doing. I didn't give up anything else. I just rearranged some of the hours in the day. I stopped watching mindless TV, I stopped doing some of the great movies, the great shows. They all suffered a little bit until I found my rhythm.

Guy Kawasaki:

You attribute much of your success to your mentors and now you are being a mentor. Can you give us insights into finding a mentor, using a mentor, optimizing mentorship? And then flip it around, how does one be a great mentor?

Chandrika Tandon:

So in terms of finding a mentor, one has to look at two sides of the coin. One is, people will very openly and actively and energetically mentor you if you have done something good for them. There's something that they have to see. Every mentor of mine were mostly some of my teachers and I really worked very hard in their classes, they remembered what I did in their classes. So they were my best mentors. And I can name them from the time I went to lower school, kindergarten, I've had mentors and my headmistress. But I did very well in school, but it wasn't that I was academically good, I just took on a lot of jobs at school.

So this is one of the things I would say to my younger self and to everybody else. You don't just walk into somebody and say, "Oh, please be my mentor?" You have to do something, go beyond what is your call of duty. A lot of my clients have really stepped up for me. It's like a cycle of karma, but I did a lot for them in years when I didn't even know I was doing a lot for them. Because I didn't care as much about myself, I was very focused on their success or the institution's success. Karma has got a very long reach and it comes back in good and bad ways and this is like the great karma coming back to help you.

Now, the second side of this brilliant question you asked me is, how do you become a mentor? This requires a generosity of spirit. It's so easy to decide not to do anything. There's so many other ways one can spend your time. To decide to be a mentor, it's not just saying, "Oh, I'm your mentor." Very often it requires time, it requires many sessions with them, it requires sometimes putting yourself on the line to help them and really make sure when they're in a difficult situation to help them through it.

So there's so many shades of responsibilities that being a mentor carries and very often younger people are afraid to come and ask you about it. So you have to seek out opportunities. And I'm very lucky because being in a university and being very available gives me a lot of opportunities to connect with many kids.

Now, it's conscious and unconscious. I think many times many kids write to me and say, "Oh, I heard you speak. I heard you say this. I heard you do this. I was inspired and I'm going to do that." But I'm going to say one thing to you and this happened to me this weekend, I was in Washington DC. I was training a group of high school children to sing. We are going to sing together in two weeks. There were 250 of them. And one of the kids asked me, "Oh, I'm so inspired by you. How can I follow in your footsteps and what advice do you have that I can follow in your footsteps, and so on?"

And what I said to her, and this is something I've been thinking about all weekend, I said to her, "It would be most awful if you followed in my footsteps. Because what you have is footsteps that are so giant, with so much power and so much potential that you're going to be creating big footsteps and big strides and big paths for yourself.

Take lessons from everyone, good lessons, bad lessons, but it's up to each and every one of us to create our own footsteps, our own strides, our own paths." And I think to me, the greatest power I want a lot of young people to have is this power of curiosity and this power of asking questions and the power of asking for help, which will give you apparent and less apparent mentors who will have great impact in everyone's lives.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, let's say that you have paid it forward, as you describe, and now you have a mentor. How do you optimize it? How do you not waste their time? How do you get the most you can? How do you make it mutually beneficial?

Chandrika Tandon:

Very often when people think about mentors is around a couple of areas. One is they want advice about a tricky situation they're in or sometimes they want a network. They want you to connect them to something so that they can go forward in some way. I think often when I see these networking as the core idea, I think it works less well than when you want genuine help from someone.

Somebody said this to me at a very early stage in my life because I was very ambitious and I was very focused on I want to get this and I want to get that. And that person just said, "Will you just tell me why you're really here? Are you here to really seek my advice or are you just looking for something?" This was when I was probably fifteen. It was not exactly these terms, but some variation of this conversation.

That stuck in my mind forever because I think when you just go for take from someone, it doesn't work as well. So I think one has to really be clear about what you're asking for and be genuine about that and people are more ready to give advice and then very often the people that have a good heart or have an open heart and can help will help. You have to trust that.

Guy Kawasaki:

But what can a fifteen, sixteen, seventeen, eighteen, nineteen-year-old kid do for a person like you? What's that part of the bargain?

Chandrika Tandon:

It's not a question of doing something for me. It is just that you want to have a sense that the conversation you are having with that person is really important and valuable to that person. I don't talk to fifteen, sixteen year olds as much every day, but I definitely talk to a lot of eighteen, nineteen year olds. That is 60 percent of my life of people that I talk to. And most of them have lots of great questions, they've got big issues that they're wrestling with, they have big ideas that they're dealing with and sometimes they have a specific problem they want help with.

I'll give you an example. We had, and this is a different context, there was five or six, actually more, there was about thirty-one of them that represented probably about twelve groups of students that were all looking for help and mentorship for each of their associations. The ones that shone were the ones that were so clear about their issues and were honest and open and authentic.

You really wanted to figure out what to do because they were so passionate about what it is they wanted to do. They were so passionate about what idea they were trying to pursue. And they dragged you along into their vision. It's not too young to have a vision even if you are fifteen or sixteen or seventeen. I know all my visions were from a very young age.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'd like to be very specific. Give us an example of a really good question that you could ask your mentor and give us an example of a question that wastes people's time of a mentor?

Chandrika Tandon:

I haven't quite thought of it that way. Somebody very often you don't even know is a mentor. It could be just a professor when you're just walking into them, maybe haven't been as connected to them in the classes or whatever and then you just go in there and then you want all sorts of connections to different schools or different recommendations or lists of different employers. You haven't come prepared. That to me is a kind of what I would call a less prepared version of going to a mentor.

A more prepared version would be the flip side of this. The great examples I'll tell you is when somebody comes and tells you, "This is the club we're all trying to build, we've won all these prizes, but we are short all these ideas. We really need help figuring out where to go. Here are the three or four things we've done on our own. Do you have any ideas that you want to add?"

That was a very thoughtful way to approach this. And they didn't just do it to me, they did it with three or four very senior people. And they were very clear, by the time they were done, they'd not just raised everything they needed, everybody connected them to other corporations they knew and this club got much more than what they needed. But I think that to me is an example.

Because they had done their own homework, they knew each one of us, they had done their research on us, Google is ubiquitous. So they knew what they were saying, "Can you help us in these things? Can you help us find somebody to speak? Can you do this?" But they were so passionate, they weren't asking for favors for themselves, they were asking for favors for an idea that was bigger than themselves.

What is wonderful is that the children, what I've seen, and we have many thousand students at our engineering school at the NYU Tandon School of Engineering, I learn from these kids every day. We are talking about questions and so on. These kids are so hungry, they're so hungry, not just for themselves, they're so hungry to change the world, they're hungry to make a difference. And yes, they're hungry and ambitious for themselves too. Nothing wrong with that. That power is what children, kids, students, everyone needs to bring into whatever it is they're doing and then people will come to you because they're so attracted to the power of your passion.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. Great answer. I would like to hear your advice for raising powerhouse daughters like you and your sister.

Chandrika Tandon:

We all have different parenting styles. I'm going to tell you one thing. I was in Prague recently, it was on June 30th. And it was a performance I was doing with thirty some Ukrainian refugee kids, from the ages of three to twelve. With the Kroky Dobra, which is a refugee center and they're really working with families that have been displaced. Now, as part of this, the parents wanted to have a question and answer with me, but funnily enough, the questions that came to me were not from the parents, they all came from the children.

And all of them asked me, "What kind of mother were you? Were you a good mother? Were you a strict mother? What kind of mother were you?" And I was thinking to myself that this is a question that I have asked myself over the years, and I've also asked myself this question in the context of the last twenty years as my own personality changed. And the Chandrika of twenty years now versus the Chandrika of years before, in my forties.

And I think part of being a better parent for me has really become a greater awareness of myself. Because very often my vision of what it was about being a mother was to be strict and to be tough. And that's what I knew. There were lots of rules. But the one thing I think I subscribed to is setting very high expectations for your child, that there was not an option that she could not go to school, that she could not go to college, that she couldn't get a master's degree, that was simply not on the cards.

She could choose to do whatever she wanted with that framework, but she had to have a superb education. She didn't have to go to any particular school or study any particular subject, that was a non-option. So that was given almost from a very young age that she would go to college. So the expectations were high. She could have chosen in between if she wanted to take a year, take two years, do something else, come back, it's okay.

But come back, we hoped she would. And it wasn't that we forced her, but I think we inspired her that the possibility of education would just open a world to her that she cannot appreciate. And when she appreciated it, it might be too late for her because life would've intervened. So setting expectations I think was very important. I think the part that I wish I had done better, if I was being really honest, is that I wish I had been more compassionate with myself and with her.

And in my profession, you're always looking at what's wrong and you think your role as a parent is to make them perfect in some way. But I think as a parent, to really let their light shine has got to be the motto of one's existence. And we need the introspective ability to be able to understand what is that light that each child has. And you need to understand your own light because the other thing that I think I did at times, much less so after I got aware, is your definitions of success mean nothing to what her definition of success might be later on.

And I think you have to honor that and really applaud that, not just honor that, even if it's completely different from you. So I think with my daughter and now with my grandchildren, of course, it's a different role. I think that's the pathway which I've been finding in a much better way than I did in my early years.

Guy Kawasaki:

So you just explained how there was a framework of she had to have an education, but what if she came to you and said, "Mom, I want to be a musician. I don't want to go to college. I want to be a musician." What would you have said?

Chandrika Tandon:

I would've, which is what I've said to every kid at Berkeley when I was very involved with Berkeley, a school of music. "It's wonderful. Do your music and go to the best school for music. But don't forget, you still need life skills." It's pretty important. And in fact, this was my big theme. Look, even if you're a musician, I think it's important, what are the basics of life?

You need to understand the basics of finance, the basics of balancing your checkbook, the basics of dealing with a contract, basics of knowing what's happening in technology. The whole industry is getting upended by a lot of this stuff. If you have the ability, if you've got the wherewithal, why would you not get a well-rounded education while you're pursuing your passion, whatever that is?

So yes, if she'd come back and said, "I want to be a musician." I'd say, "Wonderful, do it. But you are also going to have some additional things." And by the way, I've been a firm advocate of this. I'll tell you, when we advertised for a job, this is a few years ago, this was an administrative assistant job, within one hour we had 400 applications and they were all from kids, many of them who'd gone to music schools and were just musicians. If you're a musician, it's wonderful, but you also need life skills, you need livelihood skills. And I feel very strongly about that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wait, so your point there is that yes, you can aspire to be a musician, but you still need to pay the bills?

Chandrika Tandon:

It's not just pay the bills, you need to have a basic understanding of how life works. Being a musician doesn't mean you have to ignore everything else. You can spend 80 eighty of your time on music and spend 20 percent of your time making sure you do other things so that you become a well-rounded human being in terms of living life.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. So I asked the advice of raising powerhouse daughters. Now flipping it around, what's your advice to become a powerful, effective, accomplished woman?

Chandrika Tandon:

Nothing's handed on a platter to you because you are anything. If you're a model, you have to work really hard. If you're a musician, you have to practice for hours. I think immersion in that craft, whatever the challenge is in life, you don't have a choice. So to me, once you have that source of power, it doesn't matter what your other challenges are, but you have this strength that you have going for you. So to me the second piece of this is inclusion. People have to understand.

And inclusion is also another part of it with human beings. Even if you end up working with people, you're going to have to work deals and machines and everything don't make the world, people make the world. So you have to be able to celebrate differences of people, work in harmony with different cultures, different people and see the best in everyone.

So that to me is the second part of finding your own power. And the third piece, which I spoke about, I'd say introspection. You have to go deep inside and understand your own confidence, your courage. We talk in the business terms and spiritual terms; we speak of being inner-directed and outer-directed. If your entire day is about, "He said that. She said that. I'm good because you said that." If you start to focus very much on what other people are seeing, you will be, as a major spiritual master calls it, a football of everyone's opinions. And you will never gain power that way. So you need time to introspect.

In fact, if you ask me what is the greatest advice I would give young people now is reading, writing, arithmetic is incredible. We learn to manage all these academic skills, but you have to find a way to get inside yourself and take the time to understand what makes you angry, what makes you happy, what makes you sad. That's when you'll be able to create success for yourself. It's not how much money you make or whatever, it's when you feel happiness and peace inside. So to me, the three I's is one way I think about it, but there are many ways I think about this question.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay.

Chandrika Tandon:

So when I think of finding one's own power, sometimes I think in terms of a framework of the three I's. And the three I's in my simplified way of alliteration is immersion, inclusion and introspection.

Guy Kawasaki:

A point of clarification. Earlier you said, "I am perfection." Could you explain exactly what you mean by that?

Chandrika Tandon:

This is a really important point. I spent a lifetime thinking that I wasn't good enough, that I'm a perfectionist, that I need to do better. Being a perfectionist was something I wore. It was like a badge of honor. And what that did for me is create a lot of stress because you're always found wanting. You're not compassionate to yourself because you are always saying to yourself, "I'm just not good enough. I could have done that better. Oh goodness, I wish I had not done this or wish they had done this differently. I wish everything was what was not.”

And by the way, if one were to look at it that way, you could spend a whole lifetime looking at what is not. You can look today and say what is not. Or we could look yesterday and say what was not. And then we can start to worry about tomorrow and say what could not be not. So that was what my frame of reference was. Perfectionist. I need to get somewhere.

Now, the big change that I've gone through in the last few years is I went from saying I'm a perfectionist who's trying to get someplace to this whole framework which says, I am perfection at this moment. What does that mean to me? It means that whatever is happening now, as long as I do my very best and that I will try to do as much as I can. And that I have to believe that everybody is doing their best and the moment that's come together at this moment, at this point, is a perfect moment. It's meant to be.

And that's taken away 80 percent of my stress because I'm no longer trying to change something, get somewhere, go somewhere, critique something. Yeah, there's always things that can be better, but right now, this is a perfect moment. Like this moment is perfection, I'm talking to an incredibly interesting person and we are having a great conversation. And this to me is perfection. There's probably lines I could say differently, there's probably things we could all if we wanted to go into that space, but that's not the space I'm in. I just appreciate this moment of perfection.

Guy Kawasaki:

All I can say is “Hear! Hear!” to appreciating every moment of perfection. This was Chandrika Tandon. What a great episode. I guarantee you it will help you be remarkable and make a difference in the world. Speaking of, Madisun and I have published a book, it's called Think Remarkable. I hope you'll check it out. It reflects the wisdom and insights of 200 guests plus forty years of working in tech. I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People.

My thanks to Chandrika Tandon for appearing here and also the Remarkable People team. That would be Jeff Sieh and Shannon Hernandez, design engineers supreme. Madisun Nuismer, the Drop-in Queen and producer and co-author. Tessa Nuismer, who prepares me for these interviews and monitors the quality of our transcripts. And then there's Luis Magaña, Alexis Nishimura and Fallon Yates. This is the Remarkable People team. We're on a mission to make you remarkable.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply