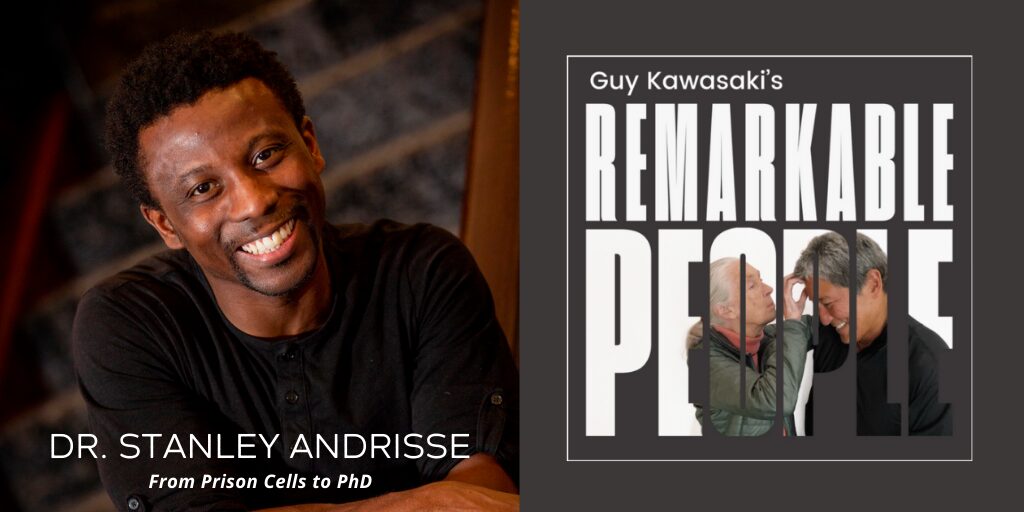

Welcome to Remarkable People. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Stanley Andrisse.

Stanley’s journey is one of resilience and redemption, an awe-inspiring transformation from a past marked by felony convictions to becoming a renowned endocrinologist scientist and professor at Howard University College of Medicine. His remarkable story has now been encapsulated in his new book, From Prison Cells to PhD.

In this eisode, you’ll discover the true essence of hope and transformation. It’s a tale that will challenge your perceptions and remind you that, even in the face of adversity, one can achieve the extraordinary.

In his book, From Prison Cells to PhD, Stanley provides an even deeper insight into his experiences and the journey that led him to where he is today. It’s a story of resilience, second chances, and the power of education to change lives.

Join us in this illuminating conversation with Dr. Stanley Andrisse, a living example that change is possible, and second chances can lead to remarkable achievements. Get ready to be inspired and uplifted.

Tune in to the episode now and embark on this transformative journey with us, and don’t forget to check out Stanley’s book for an even more profound exploration of his story.

Please enjoy this remarkable episode, Stanley Andrisse: From Prison Cells to PhD.

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Stanley Andrisse: From Prison Cells to PhD

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. We are, as you've heard, on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me today is Stanley Andrisse. He has one of the most powerful stories in our podcast. He overcame incredible odds to transform from an incarcerated teenager to a scientist and author.

Stanley grew up in Ferguson, Missouri and got into trouble at a young age. By his early twenties, he had amassed multiple felony convictions and was sentenced to ten years for drug trafficking. The prosecutor claimed he was beyond reform. While in prison, Stanley discovered a passion for science. He studied diabetes through phone calls and letters with a mentor. After his release, Stanley earned a PhD and MBA and became an endocrinologist at Howard University College of Medicine and the Georgetown Medical Center. As a professor, his groundbreaking work is about insulin resistance pathways. As an author of a book called From Prison Cells to PhD, he shares his story to inspire systemic change.

I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People, and now, here is the remarkable Stanley Andrisse.

Being on the straight path of study and hard work, how is that ever going to compete with the seemingly easy, exciting life of dealing? How are kids supposed to pick the hard path, the slow path, the less lucrative path?

Stanley Andrisse:

You start out right with some heavy-hitter questions there. That's a tough one. I answer that with another question. Why do the dominant cast individuals see that path as an attractive, doable, achievable path? So I think the question is, why is there certain groups of people in our society that society creates this imagery that it is not an attractive path for them?

I think science is quite exhilarating. I think the things that I do and the new ideas that I come up with in the field of science and endocrinology is quite exciting and exhilarating, actually, but how do I get a fourteen-year-old, fifteen-year-old to see that? Maybe actually, we are not that good at getting a fourteen, fifteen-year-old no matter what side of the tracks they come from to see science or accounting or writing books as something exciting. It's just something that happens over time.

So I would challenge that question with maybe that's not the real thing that we need to be doing. Maybe at that age, it's okay for someone to not yet see a path like science as something that is fun or exciting. It's just part of being a fourteen, fifteen-year-old teenage mind.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah, but as your case has proven out, it takes an act of God to get off that path, right? You're lucky your sentence went from seventy to thirty, but how often does that happen?

Stanley Andrisse:

It often doesn't happen for people that look like me, but it does often happen for other people that don't look like me, and I explained that in my book in that there was a couple of individuals that were just as deep as me that got caught up but they didn't look like me and society, the judge said, "We're going to give you another shot at this because I think eventually you will see that there's a better path for you in this world," but they didn't see that for me. That wasn't the way that the judge saw it originally, and I should say, really, the prosecutor more than the judge even.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, that prosecutor said to you, "You're never going to change," right?

Stanley Andrisse:

Yeah. I think the prosecutor essentially was pushing for twenty years to life in prison because she felt that I had no hope for changing or she stated that whether she felt that I argue that all the time, that I really don't think that she truly felt or believed that. She said it because the system encouraged her and incentivized her to give harsher sentences to people that look like me and to people that came from the places, North St. Louis. I was from a primarily Black area in North St. Louis and I got caught up in this predominantly White area and she was incentivized to sentence people like me for longer periods of time.

When I say incentivized, she was a young prosecutor that eventually moved up the ladder into being a judge, and a judge is in elected position that, really, the system is set up where the judges that make the decisions on things like law and order and should be fair. It's a political position. They really make their decisions based on what their people want them to make their decisions. In order to stay in office, they have to please the community that they're in.

In that particular community, there was a lot of White flight going on into this particular area out of St. Louis City. There was then a trail of more affluent Black people that were able to move into this particular area and the White individuals were not very happy about that. One way to keep Black people out is whenever a Black person got caught up in that area, let's make sure we let them know that if they come out here and do any type of thing, the life sentence became the modern day noose. That was how they started hanging Black people instead of just putting them out in the streets.

Thousands upon thousands, tens of thousands of people, Black individuals began getting life sentences in these thirty, forty, fifty, 160. Why would you give someone three life sentences? Even if you die and somehow get reincarnated, we're going to lock you back up, and then if you happen to get reincarnated again, we will lock you back up. You have three life sentences. You will never see daylight. How does that make sense?

Guy Kawasaki:

There's lots of things I read in your book that made no sense to me, and I'm going to try to hit on them. When you look back, and I don't know any other word but blame, when you look back, who or what do you blame for you turning to dealing drugs?

Stanley Andrisse:

There's a chapter in my book and the book is called From Prison Cells to PhD: It's Never Too Late to Do Good, and it's never too late to do good is this phrase that my father used to tell me. Hopefully, I will get into talking a little bit about that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Sure.

Stanley Andrisse:

Interestingly, I'm on a Facebook friend who was the second biggest dealer. He was my first or second big time dealer, but the first one, he was connected with the Mexican cartel. He was just moving crazy amounts of drugs for an eighteen-year-old. He was just a teenager and he was older than me. I think I was sixteen or something at the time, and we're still connected. He ended up doing some prison time as well. He's turned his life around and he just posted on social media and was sharing how he's so happy that he's a changed person now.

Then he had other people commenting, and this girl commented, I don't know this girl, but then I looked at her picture and I checked her out. She had a husband and beautiful children and looked to be living a pretty nice life. My friend on the other hand has led a very challenging life and he was in prison and all, as I just mentioned, and he was this big time drug dealer, cartel connected as just a teenager. He told this girl that she was the reason she asked in fifth grade, she was a cute girl, she asked him if he could get some weed and he got his first little bag of weed to try to please her, and that was this first sale that he ever made. Then he ended up a couple years later becoming this big-time cartel connected.

I shared that just to say how simple it actually can be. It wasn't these are bad people. I actually opened the first lines of my book, it's contrary to popular belief, "Drug dealers are regular everyday people." Then I opened the book up with talking about this family event that I was at where just like him that I just explained, we are humans that want love and care about those things. So how I got involved was really just a combination of things, but very similar to that situation.

I started selling drugs just to smoke a little bit with my friends. Then one day, I was just sitting with some friends that were obviously not on the right side of making good decisions, but they presented this person and opportunity presented itself. Somebody lost their drug dealer, and they needed a new drug dealer, and I was really just smoking a little bit, but I was like, "My guy, I think, I could get that amount of weed. I think I could solve that problem there. I'm just going to help this other friend solve this problem by getting a little bit more weed."

Then the next thing I know I'm getting ten pounds of weed every other day, and then all of a sudden I'm getting 100 pounds of weed every other month, and then all of a sudden I'm getting 300 pounds of weed and now everyone that I know carries guns and everybody's selling pills and cocaine. It just happened.

Guy Kawasaki:

So you often hear both users, but in general people are saying, quote, unquote, "It's just weed." So from both the users and the dealer's perspective, what's your opinion of this concept? "Eh, no big deal. It's just weed. It's not the really hard stuff."

Stanley Andrisse:

So that's obviously very interesting now that a large portion of our country has legalized weed, and to some extent, weed is less of a dangerous drug than, say, alcohol, for instance. So there's that side of the argument. It's not just weed though. So first, selling weed is very different. The amount of money and the amount of drugs, it was dangerous. So it definitely wasn't just weed because it was money, it was the amounts of money that people would kill for, literally.

So there's no way that you can say that it's just weed if it's that type of level of dealing, but at the lower level, I would caution against people thinking that it's just weed because it's the old saying of the gateway drug, but if you're dealing, it can lead to bigger things, but in terms of its use and the danger of its use, I do think that it is not as dangerous of a substance as alcohol is, and alcohol is more widely used.

Guy Kawasaki:

You never hear of someone drinking alcohol and becoming an alcohol dealer. You could make the case if it's, quote, "just weed" and it's less harmful than alcohol and weed is controlled by the government and all that, then it's okay, but it doesn't sound okay.

Stanley Andrisse:

Well, it's the illegal aspect that wasn't okay because I think ten, fifteen years down the road, we will move to where it is like alcohol when you remove the Black market aspect and when you do the research and dive into it. The opioid epidemic has drawn a lot of medical research into the field of substance use, and they've moved to the place where they actually open up, I can't think of the name of them, but they're facilities that people can come to, and use heroin and use drugs and they can use it safely though.

It's the Black market aspect of things that makes weed and anything that you're doing illegally so dangerous is because people will make sure that you don't bring it out of the Black market because if you bring it to the police, you could get me in a lot of trouble. So now I have to do nefarious things to make sure that it stays in the dark, but if we bring it to the light and we remove the stigma of it, we remove a lot of the danger.

Guy Kawasaki:

By the way, we're going to spend a fair amount of time on weed and prison and crime, but ultimately, we're going to get to your book because the real purpose of this, but for people to understand how great the book is, they got to understand where you're coming from. As you were starting dealing, did your parents or adults or other people warn you off, and why didn't you listen? Did you think you're going to be the person who got away with it? Surely you understood most people either got killed or imprisoned. What was in your mind that said, "No, I'm going to be the guy that threads the needles," so to speak?

Stanley Andrisse:

In multiple different instances within the book, I used the phrase we were teenagers, and to emphasize this idea that we know now that the human brain is not fully developed until a person reaches the age of twenty-five roughly, and the part of the brain that's not fully developed is the ability to see long-term consequences. I often equate it to I have a beautiful five-year-old daughter and an amazing soon-to-be two-year-old son. When I had my daughter, there's an app for everything. I had this app that told us every week the new development stages, and I just wanted to be on top of everything of raising this tiny human.

One week came up and it said that a baby just waves their arms around sometimes and there's a point in their development where eventually they realize that these things that are waving in front of their face is actually attached to their body and it's actually them and they're actually amazed at it. So you can see this point in the baby's development that they're so amazed at seeing their hands like they're tripping or something. When you think about how powerful the brain is, the brain literally was at a place that this thing that was attached to them, they could not realize that this thing that was attached to them was attached to them.

The brain is this powerful thing, and when it hasn't developed something yet, it's really just not there. All of a sudden, they can tell that this thing waving in front of them is their hand. When we say the part of the brain that understands consequences isn't there yet, I couldn't see it. We were teenagers. That goes back to your question and my response on the first question that you asked is that the thing about it is all teenagers are making poor decisions. It's just that certain people get punished more harshly for the poor decisions they make, and certain people, eventually, the society says that, "You can become this," but then society says, "You can't become this," for certain others.

For me, as I was writing the book, there was a chapter where one of the drug dealers that I was dealing with, this very dangerous guy, happens to be the same guy that I was just telling you about. I was going to pick up some drugs from him, about twenty-five pounds from him, and he has hundreds usually. I walk up to his house and it looked like somebody had broken in. This is a person that I know had just purchased, literally a couple days earlier, he was showing off his AK-47. He was like, "I just bought this for 20,000 dollars," and was shooting it off and was crazy. I see that somebody broke into his house, and I snuck into this very dangerous persons’ house.

Guy Kawasaki:

You went around the back, right?

Stanley Andrisse:

When it looked some crazy stuff was going on in the house, and yet my brain told me, "Hey, this looks real crazy. Let's get a little crazier though. Let's go inside and find out what's going on." Why? I look back at that, I'm like, "What are you thinking?" I'm writing it and I'm thinking, "This couldn't be. What? Why would you go in there?" and I just don't know. I don't know.

My brain was at this place where it just didn't see that far. I was good at math and I'm a scientist. I didn't all of a sudden just become smart. I was smart back then too, but for some reason, I walked into this very dangerous situation, and I walked into a lot of dangerous situations.

The only thing that really makes sense is that I was this teenager, that one, as a teenager, the brain is prone to not seeing long-term consequences and thus making poor decisions because they don't see those long-term consequences. Then I was conditioned by society to think that I should be reacting and doing things in a certain way and making certain types of decisions.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. I want to switch a little bit to prison because there's a lot of wisdom in your book about prison. First question is, how does one physically survive in prison? The next question is I'm going to ask you, how do you mentally survive? So that's common. So physically, who to trust? How do you pick your alliances? How do you not get killed?

Stanley Andrisse:

I think the way you survive prison is actually a mental psychological game. You survive the physical aspects by understanding the way to mentally and psychologically survive because physically, physical harm can be brought your way if your psychological and mental state is not in balance.

So if your psychological and mental state are in a place of somewhat balance or at least consciousness, less physical harm will come your way, but the thing about prison is that you've just been told that you've just gone through a sentencing process that basically says you have a mental problem, that's why we have to outcast you from society. You're thinking you walked into this drug dealer's house that was just shooting off AKs, you're thinking is effed up.

So you've already been told that your mental is effed up. You have a psychological problem. Then you walk in, and a bunch of other people have been told they have psychological mental problems. The truth is that a large percent of people do indeed have neurodivergence where they have different types of mental health issues before they even step foot into prison, but then it's just exponentiated through the process of being sentenced and going through incarceration. Then you're not able to be a real human and express normal human emotions in prison.

For me, for instance, maybe we were going to talk about this in a little bit, but I ended up losing my father to his battle with type two diabetes and he went through a challenging situation. Losing someone and having someone be sick, you can easily want to shed emotions, crying or being depressed or being angry and yelling. Crying could literally bring physical harm to you. If you didn't check this regular human emotion, it could literally bring you physical harm. Yelling, screaming, and other aspect of potentially going through the emotions of grief could literally bring you harm.

So it was really about understanding how to get your psychological self and mental health in a place of balance that helped you survive prison, but the thing that so many people that I witnessed had significant challenges surviving prison was because their psychological and mental health was not in balance, which when we think about it, why aren't we doing more to help people?

We know all the things that lead to prison, we know the process, but the way the prison system is, the people that act out, they just further get punished. They get put in the hole and segregated where their mental health becomes even worse. It's crazy. It's literally crazy the amount of time they put people in a tiny box. How could somebody think that's going to help this situation out? It only pours fuel on the flame for this person who is already volatile. It's crazy.

Guy Kawasaki:

So what are you saying in terms of advice? If you want to survive prison, you've got to get your mental and psychological states in balance, but what does that mean? When you're alone at night in the cell, what are you thinking about? Are you thinking about getting out, you're thinking about revenge? What should you be thinking about?

Stanley Andrisse:

I personally poured myself into books. So first, even before I eventually started pouring myself into learning, I read my first scientific article on diabetes while I was incarcerated. Then I started reading a whole bunch more, and that is, of course, the field that I'm in now, but even before that epiphany came, I would just read and read. Literally, reading just took you away from physically having to be present in some of the prison BS. You literally just weren't out on the yard, you're reading. Then I was an avid journalist.

So there was no psychologist or anybody helping me through this. I happen to be a journaler ever since I was in high school. So I would journal my emotions and what I saw that day and it would help me. I didn't know that I was helping myself process the trauma that was going on around me, and it gave me this avenue to, one, process the trauma and things that were going on around me, but then two, to take me away from it because it was literally taking time away from being in that environment.

Then there's the physical health aspect, which a lot of people do in prison because that's one of the main things to do is get big and buff, but that does help your mind as well to be in this state of physical fitness. Then I think there needs to be this aspect of some people will say it's putting it into God's hands. For me, I realized that I didn't want other people telling me how I should live my life or how I should react to something.

What that meant for me was I have been offered to join a number of gangs, and for me, I saw it as I would rather keep my integrity to do what is right and potentially have harm come to me because I was doing the right thing than to not have maybe harm come to me, but knowing in my soul that I'm not doing what my soul wants to do. So when I got to just letting my soul be itself regardless of what the outside world would think of me, and that's a challenging place to get to in prison.

Guy Kawasaki:

A lot of your book deals with the struggle of inform or not inform. So with hindsight, what's your analysis of, cost benefit analysis of being an informer?

Stanley Andrisse:

So you mean an informant to the police?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Stanley Andrisse:

So as I got to this place of really letting my soul make my decisions, and that is this integrity, and I personally believe that deep down inside a person's soul really understands this concept of doing good. Whether their actions and behaviors that matriculate out into the world is something completely different, but the world in prison will tell you that there's a lot of sociopathic people that just are very harmful, unrepairable people, but that number is the way society portrays it.

From my understanding of both research and just my personal experience, society's perceptions is completely wrong. The percentage of people in prison that are sociopathic, even people that have committed murder, the percentage of those individuals is very slim in terms of unrepairable and their soul being bad. When I was out on the streets, and I still believe that loyalty is one of the top qualities that I possess, and now I just don't make promises in the ways that I used to make promises, but if I make a promise to you, I personally think that to me, my soul tells me that the right thing to do is to keep my promise to you, and if I'm not going to keep my promise to you, then I should not make the promise to you.

In terms of informants, in the streets, the people that I was hustling with, we were married to each other, we said our vows and we became married to each other, and we promised to each other that we wouldn't go to the police and do this. So to me, what I would do now is not make that promise. I would say, "Maybe I could hustle with you, but I can't make this promise that I'm going to give up my mom and my loved ones for you," But that's the promise that I made. I basically said, "I'm hustling with you. I will give up my life. I will lose my family to keep this promise." So the problem I made was making that promise. I don't think that once the promise is made, personally I think that you've made it and you shouldn't break it.

Guy Kawasaki:

I didn't quite understand in your book how your sentence got reduced and you had this opportunity to get a PhD. Can you just explain how did Stanley achieve that?

Stanley Andrisse:

I think you're asking two questions there. One is the sentencing aspect of things, and then two, how did I get a PhD, which has both literal and, of course, figuratively behind that. So one, I often like to inform folks that they need to read the book to get the deeper appreciation for that, but really, the sentencing aspect was literally an act of God almost. I have never been given a true reasoning behind why that was changed.

For the PhD aspect of things, when I go and talk, I refer back to a portion of my life when I was nineteen years old and I was in Dallas, Texas and I was picking up 100 pounds of dope, and I walk into this hotel room and I walk in and my friend is the person who greets me and he's excited to see me and he's saying, "Hey, what's up?" and there happens to be a Mexican individual. So he's speaking in Spanish.

Then I look over deeper into the room and I see an individual with the sawed off shotgun and his finger on the trigger and the barrel is pointed directly at me, but I continue to have this conversation with this friend of mine. I pull out a lot of money and then all of a sudden people's expressions are changing and they hand over this big Tupperware bin of drugs and we go about our way.

I juxtaposed that with when I'm finishing up my PhD, I had this friend of mine who thought that my PhD committee was the devil and was the toughest PhD committee. Days before my dissertation he was like, "Oh, my God, aren't you terrified? Aren't you scared that they're going to eat you alive?" Looking back at the things that I've been through I was like, "No. I think I'll be okay. I think this is okay."

Partly how I got through the PhD was I knew that I had been through challenges that were literally life-threatening and so that I could push forward in this. Then the other thing is that having been given this opportunity that I didn't understand how I had gotten it, I didn't want to mess it up. So I was going three, four times as hard as my classmates in terms of studying and wanting to do the best that I could.

So I had this extreme hunger and thirst to be the best that there was at this, which was really a sense of fear that I had no idea how I had gotten out, how I had gotten into this program. My thinking was if the shit hits the fan, at least I can say, "I'm the top student in this program. why would you kick me out?" I was working so hard for that reason, but then also having gone through what I went through, I see challenge differently than sometimes my peers do.

Guy Kawasaki:

I would say that's a mild understatement. Oh, my God. Speaking of challenges, so let me see if I got this straight. There is a prison rule that mail cannot be longer than five pages. So your friends and family had to break up all the admissions pamphlets and applications into five-page letters, send multiple letters. You piece them back together again to get the whole thing. What's the logic of that rule that you can't get a brochure in prison?

Stanley Andrisse:

The logic is punishment and laziness. So there's literally people that have to scan through and read through every word of letters that come. Your letters always come opened up. So the envelope is always sliced open and having been opened and checked for if there's drugs in it, and also read to see if there's plans on escape. So there's the five-page limit, but then there was also a limit that you could have in your physical cell. The logic behind it is punishment, laziness, and punishment that they didn't want to have to go through that much mail.

The thing that really annoyed me was not the rule, it was the fact that they were unwilling to make an exception when I very clearly showed them what this was for. Whatever you got the rule for, but you clearly see what I'm trying to do here. I'm trying to get into school.

I'm trying to do exactly what I would hope that you want for the people that come through your custody is that they want to do better for themselves. So I've gotten to the place I want to do better and you don't want to let me do that. That's what really got me is that they denied me this exception. Basically, you're no better than anybody else. Why would we give you an exception?

Guy Kawasaki:

This is because they're focusing on punishment as opposed to preparing you for a life after prison?

Stanley Andrisse:

That's my thinking is that if the focus was on true rehabilitation and true belief that people can change, then making exceptions to those types of policies, and really, it should have been clear we need to change the policy. Whoa, one of our policies is stopping a person from getting their education. We need to change that. Why wasn't that the thinking pattern that they took towards that?

Because the policy could just be changed and it doesn't even have to go through the way that our society changes where it has to be voted on, it has to be the popular vote. There's one person that could just say, "We're changing this policy," and the prison system is set up to where the warden or the head of the prison system can make that change pretty unilaterally without there being some democratic process to it.

Guy Kawasaki:

You touched on this before. As you say, it's all relative in a sense, right? I don't if I even told you, but I'm basically deaf, and the way I'm doing this is because of a cochlear implant and I'm also getting real time transcription. So I'm thinking, "Man, Guy, you're such a stud because you're a podcaster and you're deaf and you're reading live transcription," and then I read your book and you freaking can't even get letters and you got to piece them back together, and then you send your draft response to Bodie and then Bodie sends it back, and then you got to write it back, and then the other person has to put it online and, "Guy, get real, man. You have faced nothing compared to the challenges he did."

Stanley Andrisse:

I think the resilience is an individualized thing. I look back at that and I still have a pretty strong drive, but that is a level of resilience that you cannot teach. What you've just explained is you were placed in this situation that I've never been placed in and many others have never been placed in, and you individually found the resilience to get to where you wanted and needed to be.

Guy Kawasaki:

You had these two great stories about how you became friends with Frank the racist and Mark the gay. What's the life lesson there?

Stanley Andrisse:

That is the aspect of I'm going to make decisions on where my soul sees being right and being comfortable with it regardless of what the outside world sees. I think there's just a level of integrity that you shouldn't be driven by the way the world wants you to be. You should be driven by your internal guidance of what is right and wrong and what is right with your soul. To me, I think that a lot of times, particularly dealing with the ideas around homophobia and different aspects of why people may shy away from certain people or certain things is because of what the world might think of them.

So I moved to this place that I would literally rather someone bring harm to me than not do what I feel is right with my soul. Once you're in that place, if you end up with harm being brought your way or someone, even worse, taking your life, my soul will rest knowing that I was in the right, that it was doing what I felt was right and good for the world. That's a place that's quite comforting, actually. You have this level of comfort with yourself that you come to this place of you're not directed by what the world wants you to be. For so much of my life, the world's influence was a big driver of how I thought I should be acting and behaving.

Guy Kawasaki:

With Chaminade and Dr. Shang, they stopped supporting you because of peer pressure. They found out your record, et cetera. What are they supposed to do? What is society supposed to do when they find out something like that? Just stand by you and deal with it or ... I could see both sides of the argument. What do you think?

Stanley Andrisse:

When I was fired?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Stanley Andrisse:

There was a couple of things that were just hurtful. Even beyond just the decision, it was that idea of promising. So for me, I had told this coach my situation, and I think it hurt him as well that he was like, "I know you're a good guy. I know you so well," and he was like, "I promise you everything will be okay." Unfortunately, that was a promise that was outside of his ability to keep. So I think it was hurtful in that way that it resulted in me wanting to pull back and not be vulnerable like, "Don't open yourself up for this hurt again."

There was just the aspect of being hurt because I told that, "We understand your situation, that you're formerly incarcerated, and we still want you," then all of a sudden to have it slammed in your face that, "You're a criminal. We don't want criminals. Oh, my goodness, stay a thousand feet away from my kids. You're a terrible person." So it was just the unexpectedness and it hurt.

Whether it was right or wrong, didn't take away from the way that it happened, made it hurt a little bit more than had I just been rejected outright and told that, "You can't get the job," and then I would've been like, "That's what always happens," but then to have the elation of getting the job and it'd be something that you really enjoy and then to have it ripped up under you and it smacked in your face that you're a criminal and the world doesn't like you, it was hurtful and painful.

Guy Kawasaki:

So Stanley, this is the big question. So why are there so few Stanleys? If you are in this kind of position, how do you become a Stanley?

Stanley Andrisse:

What I believe is that talent is distributed evenly and it's access and opportunity that are not evenly distributed. I think there are a number of other people that look like me that have been through the similar situations as me that have the talent to be where I am, but it's access and opportunity. They lack access to the resources. They lack the opportunities that happen to come my way. I really believe that we as a society and me as an individual and as the organization that I created, Prison to Professionals, we are working to create access and opportunity for people who look like me and who have been through situations like me.

So I think it's a matter of access and opportunity, and in order to start providing that, society needs to see that there are people that have talent. The first part of the equation is you have to believe there are other talented people out there that have gone through my situation and then you have to provide them access and opportunity.

Guy Kawasaki:

So if someone has in their circle of friends or family a Stanley, someone with this background, how do you treat, interact and support them? Are you supposed to just never bring it up or you bring it up? What do you do?

Stanley Andrisse:

One, I think that you do as much as possible to just respect and validate their humanity and their personhood. Words really matter. Moving away from using words like criminal, convict, ex-con, felon when you're talking about them in their presence and when you're not in their presence and just appreciating the experiences and voice that they can bring to everyday conversations. So I think you build up their personhood because for so many people that have gone through prison, their personhood has been stripped from them.

It's hard to feel regular emotions after you've gone through not being able to cry, knowing that if you're angry that it can bring harm your way or that it can make other people feel a little bit more fearful if you raise your voice in certain ways that another person wouldn't have that fearfulness of you. It's helping them understand that their personhood is valued and seen is one way to help them understand that they have those innate talents within them.

Guy Kawasaki:

Listen, I think your book is really interesting and it just opened my eyes. So I want you to take this uninterrupted moment and pitch people on why they should read your book.

Stanley Andrisse:

First, thank you for offering me that opportunity. I am a formerly incarcerated person with three felony convictions since the ten years in prison, was told by this prosecutor who was pushing for twenty years to life in prison, that I had no hope for changing the decisions that I had been making up until that time in my early twenties.

Fast forward some time, I did my time. I'm now Dr. Stanley Andrisse, an endocrinologist scientist and assistant professor at Howard University College of Medicine, the mecca of historically Black colleges and universities. Also, was a faculty at Johns Hopkins, visiting professor at Georgetown, took my hustles across seas and held a position at Imperial College London.

So I clearly didn't live up to these expectations that this prosecutor set. So I would encourage people to read the book to really help them understand how it is never too late to do good, to help them understand that too much of the way that our society views the criminal legal system is that people don't have that capacity for change. The book helps you understand that it is possible to do good, it is possible to be part of something that seems so dangerous and harmful to society, to being a person that can bring good into society.

Then the other aspect of what the book is, although it is my journey, From Prison Cells to PhD, it's not really about me. It's really about the social, political, cultural aspects of why a young Black kid from Ferguson ends up in what we now know as the school to prison pipeline and goes to prison, and then it offers ideas about how we might help change this school to prison pipeline and potentially create this pipeline of helping individuals move into higher education.

Guy Kawasaki:

I hope you enjoyed Stanley's remarkable story. To achieve what he did while in prison and then while carrying around his prison record is truly a remarkable accomplishment. I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People. My thanks to the Remarkable People team, Alexis Nishimura, Luis Magaña, Fallon Yates, the Ace design team, Jeff Sieh and Shannon Hernandez, and finally, the Nuismer sisters, Madisun, drop-in queen and producer of this podcast, and Tessa. Luckily, she doesn't surf because Santa Cruz doesn't need any more people dropping in.

Don't forget, Madison and I wrote a book, Think Remarkable. It is a book that I promise you will transform your life as you learn how to make a difference and be remarkable. Until next time, mahalo and aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply