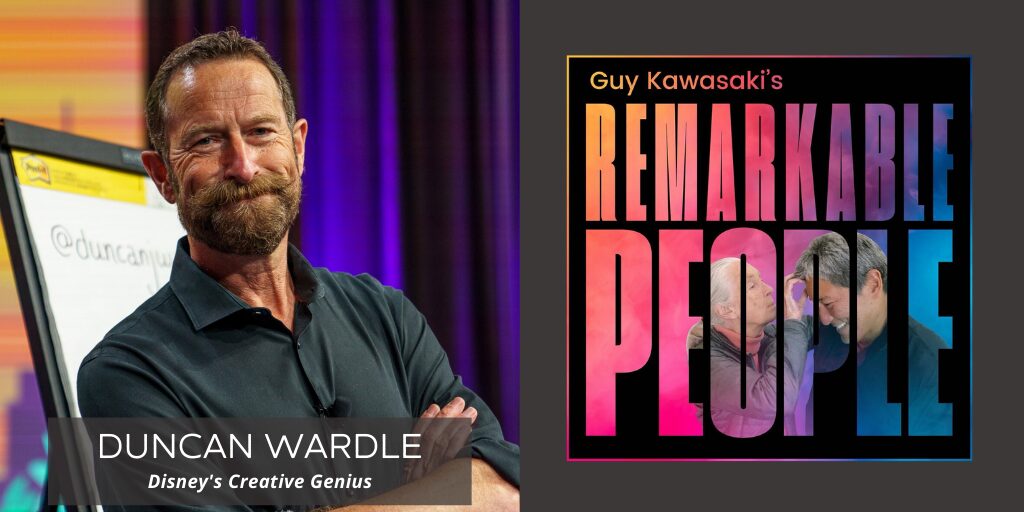

Welcome to Remarkable People. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Duncan Wardle.

Duncan is no ordinary business leader; he’s a creative force who transformed innovation at Disney during his remarkable 30-year journey. Starting as a coffee boy in London, he rose to become Head of Innovation and Creativity for Disney, Pixar, Marvel, and Lucasfilm, leaving an indelible mark on one of the world’s most beloved brands.

Duncan’s new book Imagination Emporium embodies everything he preaches about innovation. It’s not just another business book—it’s an interactive toolkit designed for different learning styles, complete with QR codes linking to animated characters, Spotify playlists, and even AI integration. As Duncan explains, “If it sits on your coffee table, we’ve failed.” The book serves as a practical guide for unleashing creativity, making innovation accessible to everyone, not just the “creative types.”

In this episode, we dive deep into Duncan’s fascinating career and his proven methods for unleashing creativity in any organization. From his infamous Roger Rabbit royal premiere mishap to “borrowing” presidential turkeys for Disneyland, Duncan shares captivating stories while teaching practical tools for innovation. His insights on breaking free from traditional thinking patterns and embracing creative methodologies are transforming how organizations approach innovation.

Let me share why this conversation matters: in a world increasingly dominated by AI and automation, human creativity becomes our most valuable asset. Duncan’s approach to innovation isn’t just about generating ideas – it’s about fundamentally changing how organizations think and operate. His practical tools, from the “Naive Expert” to “What If?” thinking, offer actionable strategies for anyone looking to enhance their creative capabilities.

Please enjoy this remarkable episode, Duncan Wardle: Disney’s Creative Genius.

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Duncan Wardle: Disney’s Creative Genius.

Guy Kawasaki:

I have to say that of the 260 guests we've had on this podcast, you have, by far, the best background behind you.

Duncan Wardle:

And it's real, it's drawn, it's painted. It's not one of those fake backgrounds. Well, I worked for this guy for thirty years. I finished as Head of Innovation and Creativity at Disney, Pixar, Lucasfilm, Marvel, but it didn't start that way. I started as a coffee boy in the London office. I used to go and get my boss six cappuccinos a day from Barrow Turn in First Street.

And about three weeks into the role I was told I would be the character coordinator. That's the person that looks after the characters that walk around. At the Royal premier of Who Framed Roger Rabbit in the presence of the Princess of Wales, Diana. I was like, "What do I do?" They said, "Well, you stand at the bottom of the stairs. Roger Rabbit will come down the stairs. The Princess will come in along the receiving line. She'll greet him or she'd blow him off."

How could you possibly screw that up? Well, that was the day when I found out what a contingency plan was because I didn't know. A contingency plan would tell you if you're got to bring a very tall rabbit with spectacularly long feet down a giant staircase towards the Princess of Wales, you might want to measure the width of the steps first.

So I hadn't. Roger trips on the top step, and he's now hurtling like a bullet, head and feet directly down the stairs towards Diana's head, whereupon he was met in midair by two Royal protection officers who just took him out.

There's a very famous picture of Roger going back like this, two Secret Service heavies diving towards him in a suit, and a twenty-one year-old PR guy from Disney in the back going, "Ah, shit. I'm fired." So I got a call the next day from a place called Burbank, which I'd never heard of, from somebody called a CMO, didn't know what they were either.

I thought I was going to be fired. And all I heard was, "That was great publicity." Was like, "I can make a career out of this." And so basically sort of great years at Disney I did I got to have some of the more mad, audacious, outrageous ideas. That's kind of what I did.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, Madisun, I think that that was probably the best start of a podcast in the history of the Remarkable People podcast. Usually, Duncan, we like to introduce the guests, but we got to get out of that box and let the guests tell their own story.

Duncan Wardle:

When people ask me to, they want me to read my bio when I get up on the stage. Do you remember the Charlie Brown cartoons? You remember the principal? "Wah, wah, wah, wah, wah." Don't read the bio, please don't. So I always do two truths to the lie. And the funny thing is when you get off the stage, you think, "Oh, this person's coming up to me. They're going to ask me a really important question." They just want to know which one was the lie.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, so clearly we are not going to do a traditional introduction.

Duncan Wardle:

Oh, no. Certain not.

Guy Kawasaki:

So I have to ask you this dumb question, but man, what was it like to work at Disney? Was it like being the Super Bowl MVP and every year you go to Disneyland? What was it like?

Duncan Wardle:

I hosted pretty much all of those guys. This was in the days before contracts. So you literally, at the end of the game, you had to get onto the field at the end of the game, grab the MVP, but everybody else was yanking your cameras and your cameramen and throwing them all over the place. Your job was just get to the MVP, get the line, "I'm going to Disney World," get them on the corporate jet and fly them down to Disney World.

That sounds easy, but except there's the MVP who doesn't want to go with you? They want to go drinking somewhere. So I got separated on the field from my cameraman, and he comes on the radio goes, where are you? I said, "I'm on the pitch at the halfway line." And somebody else goes, "I think he means he's on the field on the fifty yard line." I said, "Yeah, whatever."

So I worked for basically for, I suppose, 50 percent of my career was with Michael Eisner, 50 percent with Bob Iger. But Roy Disney was still there all the time. And I loved Roy and John Lasseter. They were the old school, but the old school which is they had less corporations. We got so tight and tidy and pretty now.

I think they pushed boundaries more. I admired them both because they broke the rules. The most successful social video I ever produced for Disney, and it was still the most successful one we ever produced, was because I refused to go through the approval process.

Which was, I'm sure if it had gone wrong, I'm sure I'd have been fired. But sometimes you have to stand up in what you believe for. I loved Disney because if you had a big idea somebody would fund it for you.

And I love working for Michael in particular because every time he walked in the door, he was always respectful, very courteous, but he'd say, "You know what, we're the world's number one entertainment company. Come back when you've got something that scares me." Come on it, all right? Brilliant. And so it was great.

And working with Bob was also fascinating because here comes Pixar, Marvel, Lucasfilm, ESPN, ABC, and suddenly you've got all these cultures who are very unique. But the challenge was everybody was better than everybody else. And so the task that Bob gave me was how might we embed a culture of innovation and creativity into everybody's DNA?

So the first thing I did was hire somebody else who knew what they were doing, thus make me look good. They were a consultant. They were never around for execution, but they were never going to show me how they did what they did or they were frightened I wouldn't hire them again.

Model number two, I'll be in charge of innovation, creativity. What could possibly go wrong? Well, it's kind of like having a legal team or a marketing team or a sales team. When you have an innovation team, you've kind of told everybody else you're off the hook, so that model failed.

The accelerator program. We bring in some young tech startups and take a fifty:fifty stake in their business for them we could scale. That's what Disney does for them. They could help us bring products and services to market much quicker than we normally did.

But we failed in Bob's overall goal, which was how might we embed a culture of innovation and creativity into everybody's DNA? And so I asked 5,000 people, I said, "What were the biggest barriers to being more innovative and creative where you work?"

Number one don't have time to think. Number two, we don't have the resources. Number three, we say we're consumer and client centric, but we measure by quarter results. Number four, our ideas seem to get stuck, diluted or killed as they move through approval process. And number five, we all had a very different definition of creativity.

So I set out to create a toolkit that has three principles, takes the BS out of innovation and makes it more accessible to normal, hardworking people. Makes creativity tangible for people who are uncomfortable with ambiguity and great.

Far more importantly, make it fun, give people tools they choose to use when you and I are not around. So I was with Disney for thirty years, I got the Jiminy Cricket, thank you for Thirty Magical years of service Bronze. And I looked at it and I thought, "Shit, I'm nearly dead. I've got to do something else."

So I left and I went home to England for a while and sat in the pub and felt sorry for myself and thought, "Okay, what do I do now?" And somebody said, "Could you come and give a speech?" Sure. And it just took off.

But see, I am the antithesis of so many other people. The word the creative drives me nuts. I'm sorry, it just does. I know some people are better at writing stories, some people are better at writing music, some people are better at acting. I believe everybody's creative. When you were a kid and you were given a gift for Christmas, it came in a huge box. It took you ages to take the toy out of the box.

Well, you spend the rest of the week playing with the box. It was your rocket ship, it was your force, it was your creative. But here's the challenge. Here comes AI.

And I was working with the engineer on that DeepMind project, and I asked her, I said, "How am I going to compete with what you do and what you are creating?" She believed the most employable skill sets for the near term will be the ones that will be the hardest for her to program into AI.

What are they? Well, the ones with which we are born. We're born with imagination. We're born creative, we're born curious. We used to ask why, why, why again. We're born with empathy, and we're born with intuition.

Will they be programmed one day? I don't know the answer, but in the short term, probably not. But the problem is then we go to school and the first thing our first grade teacher tells us to do is don't forget to color in between the lines. And then they say, stop asking why because there's only one right answer.

So I did a talk at a university of 3,000 students at university age. So I brought in one first grade class of thirty little six-year-olds and sat them in the middle with their teacher. I said, "Hands up here, who's creative?" Me, me, me, me, me. Thirty little hand shot to the air.

The other 3,000 stayed down. We are taught that we are not creative. By the time we're eighteen, most people have given up. And yet here comes AI, which will doubtless take away many roles but create new ones. But what have we got left? I genuinely believe there are things with which we were born.

Guy Kawasaki:

Duncan, has anybody ever told you that you need to come out of your shell and learn to express yourself?

Duncan Wardle:

And I haven't had a drink yet.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, if you don't mind, I'd like to ask a few questions in my podcast.

Duncan Wardle:

Fire away.

Guy Kawasaki:

So I want to hear about the philosophical impact of Disney calling people guests, not customers. What's behind that?

Duncan Wardle:

There's a tool I call how else? How by simply reframing a challenge, can you get people to stop thinking the way they always do and give them permission to think differently? So we'll try an experiment and then I'll answer your question. Where do you live by the way?

Guy Kawasaki:

I live in Watsonville, California.

Duncan Wardle:

Watsonville. So if I was coming to Watsonville and you and I were going to open a car wash together, tell me if you would, what are the three essential ingredients, three or four things we must have in a car wash?

Guy Kawasaki:

I would say good Wi-Fi is number one.

Duncan Wardle:

Okay, Wi-Fi. All right, okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

And then obviously you have to have the cars really clean.

Duncan Wardle:

Cars, yeah. What are the essential ingredients?

Guy Kawasaki:

The essential ingredients is your car comes out clean and then while you're waiting for it you're somewhat entertained. And I would say that's about it. Maybe there's a third. The third one would be that I hope that the water and the resources are being effectively recycled. We're just not polluting.

Duncan Wardle:

Okay, so now you and I are venture capitalist. We've been invited to open a new franchise of auto spas. Ooh, a spar. What have you seen in the spa? What would you like to see in your auto spa? Anything you want. What would you love to have in your auto spa?

Guy Kawasaki:

So I think what you're trying to say is that if you define it as car wash, you think of just the rollers and the sprays. But if you say auto spa, you think of manicure, pedicure, massage. You think of hippie music, you think of relaxation, you think of zen, you're not thinking of just getting your toenails cut.

Duncan Wardle:

Yeah, that's exactly how Walt used the tool. He said, July Seventeenth, 1955, when he opened the doors to Disneyland, which that's coming out for a Seventieth in a couple of months. Now I feel old. He said, we will not have any customers in our park, we will only have guests. We will not have any employees, we'll only have cast members. There'll be cast for a role in the show. They wear a costume, not a uniform. They work on stage, not backstage.

With that simple re-expression of the relationship between the employee and the customer as the cast member and the guest, Walter created a culture of hospitality that's rarely been repeated elsewhere. So now fast forward, how is it actually used in business today in 2011, if we'd asked the question, how might we make more money? We'd have put the gate price up at Walt Disney World. People would've complained they'd still come, we'd made our quarterly results.

You don't get to iterate in a post-pandemic world. So instead of saying, “How might we make more money?” We reversed the challenge. We said, "How might we solve the biggest consumer pain point?" Everybody knew what it was. It was called standing in line. And I said, "Well, what if there were no lines?" Didn't know how to do it. Again, if you know how to do it, you are iterating. If it scares you a bit, you're innovating.

So we used another tool which is about looking outside. I believe a lot of the insights for innovation come from looking outside of your industry. And we found a very small pharmacy in Tokyo, Japan that used RFID technology to enable people not to stand in line when they came to pick up their prescriptions.

Bing, welcome to the world of Disney's magic band. I'm not wearing one today. Oh, wait a minute. Yes, I am. Here we go. Do they come in red or gray in the mail? Yes, of course they do. Why? Because you'll like great to the Star Wars edition or the Mickey Jedi edition. Does it come in matching merchandise? Of course it does.

This is my room key. I don't check in or check out of a Disney resort today. It's my theme park ticket. The turnstiles are gone. My reservations for my favorite character meet and greets, my favorite rides. I can pay for food with it. I can pay for merchandise with it. I walk into the restaurant when want to walk in and the food comes fresh to me.

Had we have started by saying how might we make more money; we'd have made a 3 percent profit margin. But by reversing the challenge and saying how might we solve the biggest consumer pain point, the average guest at Walt Disney World today has over two hours free time they didn't have each and every day six years ago.

What has that resulted in? Record intent to recommend, record intent to return, and what is it you lovely people would do with your free time at Disney Theme parks? Spend money.

One of the biggest single revenue generating ideas Disney ever created. And what's the consumer doing every second of every day? They're crowdsourcing the future of every product and service Disney creates by telling what they like and what they don't. And it comes in themed merchandise.

Guy Kawasaki:

I swear I have my list of questions and I was going to ask you about this wristband case. So is this something that if you go back, it was like somebody in innovation thought of it or was it security thought of it or the hotel lobby staff thought of it? What was the genesis of this?

Duncan Wardle:

Well, the genesis was how might we stop people from standing in line? And when you're hosting twenty-five million guests a year, that's going to be tricky. And so, we looked in the theme park industry, but nobody was solving the issue. So this tool is about where in the world has somebody already solved the challenge of people not standing in line? So you look outside of your industry and borrow about the underlying principle and that's how we found the pharmacy.

But I will tell you there's another story, not specific, not pertains to the magic band. I love Ed Catmull. He always said, "Creativity doesn't follow job titles. It just comes from where it comes from." I love the naive expert. Actually, do you have a pen and a piece of paper?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes, I do.

Duncan Wardle:

Good. All right, come on then. So the naive expert, who or what is a naive expert? They are somebody who doesn't know what you are working on. What does that give them permission to do that you can't? Well, they can ask the silly question that you are too embarrassed to ask in front of your colleagues.

They can throw out the audacious idea ungoverned by your river of thinking. I define our river of thinking, the more experience, the more expertise we have, the more reasons we know why the new idea won't work, so we constantly shoot it down.

So I always bring in a naive expert. We were designing a new retail dining and entertainment complex for Hong Kong, Disney. In the room that day were the Disney Imagineers, the people you would expect. But on that particular day, I was faced with twelve white male American architects over fifty. So I brought in a young girl from China. Why? She was female, not male, under twenty.

Guy Kawasaki:

This is the Dim Sum girl.

Duncan Wardle:

Exactly right. So hang on. So I gave them the same challenge I'm going to give you now then. So I'll give you seven seconds to draw a house. Go. Come on, seven, come on, draw that house, Guy. Come on. Seven, six, five, four, three, two, one. Here's three. See? If you've drawn it. I know it's going to look like this.

So here's the thing. Everybody drew this except the young female Chinese chef she drew. Let's see if I've got a picture of it over here. So let's see if I've got it. Oh, here we go. She drew Dim Sum architecture. Why wouldn't she? She's of young female, Chinese chef. Never occurred to her to draw the house the same way we would.

On the way out the door somebody put a post-it note over her drawing that simply said, "Distinctly Disney, authentically Chinese." Seven years, the strategic brand position that guided the entire design of the Shanghai Disney Resort, distinctly Disney, authentically Chinese. The point is this, and companies don't understand it, diversity is innovation. If somebody doesn't look like you, they don't think like you. And that shockingly enough, they can help you think differently.

And I believe that sometimes we get the leadership meeting. Well, for goodness's sake, inviting somebody who's not a leader. Some young twenty-eight superstar who's been on touchscreen technology since the day they were born, virtual reality since the day they were five and they've been on ChatGPT for a year longer than any of us. But we don't because why do we do leaders and lead because that's the way we've always done it here. Well, maybe think about it differently.

Guy Kawasaki:

I got to take a rest just listening to you, but okay. So listen, I kind of know what you're going to say, but I just want you to say it for people, which is I see a lot of companies where there's like a chief innovation officer, there's a department of innovation, there's R&D specifically tasked with innovation. But should everybody in the company be thinking creatively in innovation or just these people who are supposed to be tasked with this?

Duncan Wardle:

The creatives, oh, give me a break. There was a lady, I won't go through the whole story. So we were doing a strategic pricing session surrounded by the EVPs, the SVPs and the gods from Mount Olympus had joined us for a day. It was how might we make more money? And they were all strategists and future planners and accountants and finance.

So I invited in Maggie. Who was Maggie? Maggie was a seventy-eight year-old cast member from our call center. Now why would I invite Maggie into a strategic pricing session? Let me think. She spends eight hours a day talking to our guests at the call center and we don't.

So we were just chatting during the lunch break and I said to her, I said, "Maggie, why do you do this? You're seventy-eight, you should be retired." She goes, well no dear, my husband passed away a few years ago and this keeps me company and I like making people happy.

I was like, "Oh, you're a lovely person." I said, "If you don't mind my asking, what do you not like about your job?" She goes, "Oh, that's easy, dear. My boss." I said, "Hang on a minute. Why don't you like your boss?" She goes, he makes me get off the phone. Obviously, she's there for the gossip and the chat.

I said, "If you don't mind my asking, how many people do you book in a shift?" She goes, "For every twenty calls I get, I'll probably convert one of those phone calls to a Walt Disney World vacation." I said, "Is that good or bad? I don't know how to think about it." She goes, "I reckon I could get three or four out of twenty if people would trust me." I was like, "Maggie, you're a grandmother. Everyone trusts grandmothers. You work for the most trusted brand on the planet."

She goes, "No dear, they don't." I said, "Why not?" She says, "Oh, we've got this policy called guest requests, don't suggest." I said, "Oh, God. Who came up with that title?" So I said, "What's that?" She said, "If the consumer is online and let's say it's the Valentine's Day offer. Let's say you have to book in January, travel in February, you get free carriage at breakfast with Anna and Elsa."

She said, "If the consumer doesn't mention that offer in those three specific bullet points first, I'm not allowed to mention it.” My intuition was like, "Ah, sound good." So I went off to meet the head of strategic pricing and yes, I should have been a bit more diplomatic in my response. I said, "Tell me about guest requests, don't suggest."

And he said, "It's worth x million dollars in incremental revenue." And I said, "What? By cheating people?" Probably didn't come quite out the right way. And he said, "We're not cheating people, we just don't make the offer first."

I said, "Listen, Maggie here reckons she could get three or four out of twenty you would take her out of your policy. Could you think we could take her and six of her colleagues out of your policy for six weeks to see how they perform?" Six weeks later, they were all booking three or four out of twenty. The policy went away and Disney made X amount of dollars in incremental revenue. I am a great believer though. Ideas come from anywhere. I was head of the innovation department. I think that was a mistake.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, you spend a lot of time in your book talking about “No, because” as opposed to “Yes, and” so now I understand the concept there, but can you just tell us how do you walk the fine line? Because you cannot say yes to everything. You cannot say no to everything either. So how do you decide what's yes or no?

Duncan Wardle:

I'm very clear in my signal. I say, "This is an expansionary session. Today we will be having a reductionary session. But today we're expansionists. And in this session, you don't get to say no because." And I don't let people say no because. I'll make them stand up just like an alcoholic and say, "I'm a reductionist." And we all laugh and cheer and they sit back down again.

You must clearly signal what you're looking for from people today. As long as they know they'll have the opportunity to evaluate the ideas later on, they'll stay with you on the yes and. I also think a physical room is very important. Steve created it first at Pixar. These rooms like the greenhouse or the Toy Story room, rather than room fifty. Come on, you can have the death star room. And these physical signals to everybody that when we're in this room, we don't get to shoot ideas down.

The challenge for all of us is the more experienced and the more expertise we have, the more reasons we know why the new idea won't work. So we constantly shoot it down. So I actually have an exercise that I do. Actually do you want to play?

Guy Kawasaki:

Why not?

Duncan Wardle:

Okay, so are we going to do a Star Wars party or a Harry Potter party? What would you prefer?

Guy Kawasaki:

Star Wars.

Duncan Wardle:

All right, so I'm going to come at you with some ideas for Star Wars party. I'd like you to start each and every response with the words you've heard every day “no, because” and then you'll tell me no because and tell me why not. So I was thinking we could actually take over some, ooh, the new blimp, the Goodyear, the coming out with that new blimp again and we could turn it into the death star, and we can have a death star canteen with food and wine in Tatooine.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now I'm supposed to say no because, and come up with a reason?

Duncan Wardle:

No because and tell me why not, yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. No, because the blimp cannot hold that many people. People will be waiting for hours in line to get on the blimp.

Duncan Wardle:

All right, fair. But I'll tell you what, then we do it at Disneyland at Galaxy's Edge and everybody could come dressed in their favorite character. Tall people could be Vader and small people will be E-Box. Pretty great.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well then security will go crazy because everybody will look like Darth Vader. And how do we know one of them isn't a criminal?

Duncan Wardle:

Fair point. What if we just did a twenty-four hour movie marathon, man, people could get free popcorn.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, how many people can really take a twenty-four hour kind of movie marathon? Yeah, it sounds great on paper, but how people will actually do it?

Duncan Wardle:

All right, so we'll stop there and now we're going to do the exercise again. This time I want you to start each and every response with the words yes and we'll just build on each other's idea as we go. Can we do Harry Potter?

Guy Kawasaki:

Sure.

Duncan Wardle:

Cool. So I'm going to come at you some ideas for Harry Potter party. I'd like you to start each and every response with yes and, and build on the idea. So I was thinking we could come to your house, put a sorting hat inside the front door and all the good people get the Gryffindor party and all the dark, mysterious people get the Slytherin party.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah, and then we could have this Quidditch contest, and I have a bocce court. We could convert it to some kind of Quidditch court and have everybody flying around in their brooms.

Duncan Wardle:

Yes and we could put one of those anti-gravity chambers where they could actually fly. All right, so we'll stop there. Listen, a lot more laughter, a lot more energy. And most of it became Italian for the first time. In the first exercise, do you think our idea was getting bigger or smaller as we were going through the Star Wars idea? Which direction was it headed?

Guy Kawasaki:

Smaller.

Duncan Wardle:

And with the Harry Potter idea, were we getting bigger or smaller?

Guy Kawasaki:

Bigger and bigger, yes.

Duncan Wardle:

Now we have colleagues and clients and constituents to bring on board with our ideas at work. Sometimes it's hard, the bosses and colleagues, et cetera. By the time we just finished building the Harry Potter idea together, whose idea was it by the time we finished?

Guy Kawasaki:

I hope all of us.

Duncan Wardle:

Exactly. “Yes, and” has the power to turn a small idea into big one really quickly. We can always engineer a big idea back down again. But far more importantly, any organization has the power to transfer my idea to our idea and accelerate its opportunity to get done. That is the value of “yes, and.”

But I want to come back to when I ask people, "Who are the most creative people you ever met?" People always say kids. And then you ask, "What do kids do better than you?" I say play. And then I'll ask people, "Who's encouraging playful at work every day?" And nobody puts their hand up. So let me ask you a question. Close your eyes. We're going to play a word association game. I want you to shout out. Keep your eyes closed. I can see you.

Guy Kawasaki:

I have to violate HIPAA here, Duncan. I am deaf and I'm listening through you through a cochlear implant and I'm also seeing a simultaneous transcription. So if I were to close my eyes and just depend on audio.

Duncan Wardle:

Got it, okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

Probably won't understand what you're saying.

Duncan Wardle:

That's fine. Okay, so keep your eyes open, but I just want you to shout out the first word that pops into your mind when I ask you the following question. Where are you usually and what are you doing when you get your best ideas?

Guy Kawasaki:

I am surfing and it is between sets, so I have nothing to do but think.

Duncan Wardle:

So people will say surfing, jogging, walking, playing, exercising, in the park, in the forest. And do you know, I've done it with up to 20,000 people and I get them to write it down, that one word. And I say, "Hands up, who put down at work?" Nobody ever has our best ideas at work. Why not? You remember that classic argument you were in with somebody recently.

You're a bit of a shouting match. You're angry at each other. You turn to walk away from the argument and the second you turn to walk away from the argument, what just popped into your head? The second you turn to walk away from the argument. What was it?

Guy Kawasaki:

How I could have won it.

Duncan Wardle:

The killer one liner. Yeah, that one perfect, beautiful line you wish you'd use but you didn't, did you? No. Why? Because when you're in an argument, your brain is moving in a thousand miles an hour defending itself. At work, emails, presentations, weekly meetings, compliant training. I hear myself say, “I don't have time to think.”

And when we say we don't have time to think, we're in the brain state called beta. I call it busy beta, where the reticular activating system, much easier to remember there's a door between your conscious and subconscious brain is firmly closed.

When that door is closed, you only have access to your conscious brain. So what percentage of our brain is conscious? 13 percent of our brain is conscious. 87 percent of our brain is subconscious. But everything is back here to help you solve the challenge that you're working on right now.

But when the door is shut, you don't have access to it. So what do I do? I run an energizer. What's an energizer? It's a silly exercise. Why am I doing that? To make you laugh. Why? Because the moment I hear laughter, I know that metaphorically I placed you back in on the surfboard where it is where you have your best ideas.

Is in the brain state science calls alpha, where the door is just wide enough open between your conscious and subconscious brain. You can still make an informed decision, but you can still have a big idea. I don't expect people to be playful every second of every day. I do expect people to be playful when they're trying to have big ideas. That's what children do better than adults.

Guy Kawasaki:

When I was reading your book and I came to that section about the four states of a brain, when I read Alpha, I said, "Guy, you are Mr. Alpha." I am in alpha when I'm in the shower, when I'm surfing, when I'm driving. Ask Madisun, I'm all alpha, all the time. And can I ask you a question about these four states?

Duncan Wardle:

Sure.

Guy Kawasaki:

Because you brought up a point here I didn't quite understand. So the four states are alpha, beta, theta, and delta. Now, in theta and delta, you talked about Edison and dropping a penny and then it woke him up again. And then you talk in the delta, the dreamy state about Dolly dropping a key and that would wake him up. So I didn't understand why Edison dropping a penny is on theta and Dolly dropping a key is in delta. It seems like those are very similar things.

Duncan Wardle:

Yes and no. So here's how it works. If you know the expression when the penny drops, that Eureka moment when I get the big idea, it came from Thomas Edison. He used thought for theta, he used to fall asleep at night seated on an armchair with the tin tray on the floor, and the penny was between his knees. As he would fall asleep, his muscles would relax, the penny would drop, it would hit the tin tray and it would wake him up and he'd write down whatever he was thinking.

And we might say, "Well, that's nuts. I'd never do that." Well, who had more patented inventions in the twentieth century than anybody else? Dolly used to fall asleep against his easel. As he fell asleep, he'd fall over and that would wake him up and he would sketch whatever he was dreaming.

I want to know he was smoking before he went to bed. But neither of them were unsuccessful. If you’re one of those people who gets our best ideas as we're falling or waking up, A, keep a notepad by the bed because you promise yourself you won't forget it by six o’clock in the morning.

Far more importantly, when you're working with your colleagues, I hear so often clients will come to me and say, "Could you solve something in two hours?" You're like, "Yeah. Right, sure." And the door was shut because we're stressed. And so the door between our conscious and subconscious being firmly stressed.

Brief it in a week or two in advance, give people time to go wherever they are, whether they're in the shower, whether they're falling asleep, whether they're in dreamy delta, which is way in the middle of the night.

So theta is the difference between, answering your question, between theta and delta is theta is just as you're beginning to wake up in the morning or just as you're nodding off at night. Delta is the doors are off. You're riding pink ponies and unicorns through the universe at three o’clock in the morning. Probably not the best brain state for creativity at work. I find the best brain state for creativity at work is the one that you live in, which is alpha. How do we get there? By being playful.

Guy Kawasaki:

I kind of want you to answer that question, how do you get to alpha? I don't have a problem getting to alpha, but how do other people get a problem to alpha?

Duncan Wardle:

So there's a series of them in the book. They're called Energizers. They are sixty seconds. When I walk into a room, I'll ask, the first thing I do is stand down and say, "Hands up, who's creative?" About 3 percent of the audience will put their hands up.

So then I get them to stand up in pairs and I tell person A they are the leading designer of parachutes for elephants. Person B, they're a news reporter. They have to interview person A about how they get their job done. And for the next two minutes, you just stand back and listen to the laughter in the room.

All I'm doing is opening the door between their conscious and subconscious brain and putting them back in wherever it is when they have their best ideas, when they're in amazing alpha. That's what the energizers are for. They are playfulness with purpose. And again, ask us, who are the most crazy people we ever met? Kids? What do they do? Play. This is not rocket science.

Guy Kawasaki:

I have to tell you, Duncan, that I'm almost afraid to admit this because people in California might go crazy when I tell them this. But I take three showers a day and I'm thinking in those showers all the time. And I surf once a day.

Duncan Wardle:

Plenty of ideas. An idea factory.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah. Ask Madisun, am I an idea factory or not?

Madisun Nuismer:

Yes, very much so. Always new ideas.

Guy Kawasaki:

And Madisun always says “no, because.”

Duncan Wardle:

Madisun, “yes, and” girl. “Yes, and,” come on.

Madisun Nuismer:

I'll work on it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Madisun is my beta. Between my alpha and her beta, we are an unstoppable team. I would love to find out, do you even think it's possible or does it merit doing this? But how do you measure creativity?

Duncan Wardle:

That's a tough one. I know how to measure an idea. Would that help?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes, that's close enough.

Duncan Wardle:

So at the end of the brainstorm, we finished the brainstorm and we're told we can put our three purple dots on the three ideas we like the most, the best. So we read all of the ideas, and then we look around the room and where's our boss? Oh yeah, they're over there, right? Where are they going to put their red dots? Oh, idea number seventeen. So we line up right behind them and we put our idea on our dot on number seventeen. We tell them how much we liked it too. But guess what? We didn't.

And so when the idea goes off to execution, it will get stuck, diluted, or killed because the people who are responsible for getting it done, were not passionate about it in the first place. So I have a talk called passionometer where I allow people to vote anonymously on their favorite ideas.

This is voting with your heart. Got nothing to do with the head, nothing to do with strategy. Well, this is the idea that I want to take home and tell my loved ones I got to work on this. It was one of my ideas. That's passionometer.

You want to find out where the passion of the team is first. I can get down from fifty ideas to about eight in a nanosecond doing that exercise, but it is done anonymously. Then I'll share with you this tool that I borrowed with pride from Richard Branson. I love Richard Branson.

When was the last time anybody ever called him a CEO? Never. Yes, he is. Of course he is. He's an entrepreneur. He's an entrepreneur. So think of all the things he's launched that failed. Coca-Cola, Virgin Cola, Virgin Vodka, Virgin Massages, Virgin Mobile, Virgin, you name it. So what?

Guy Kawasaki:

Virgin Bride?

Duncan Wardle:

Yes. Virgin Weddings. God, I remember. He uses a talk called Stargazer. So this is about voting with your head, not your heart. Virgin is a very elastic brand, right? Disney is a very non-elastic brand. So Virgin, he's done condoms and space travel and everything in between. So how does Virgin evaluate what new ideas and products and services they should bring to market? I use the same tool. I call it Stargazer. Let's just say for today's argument, is this idea a strategic brand fit? I'm making that up.

People would choose their own criteria, obviously. Is this idea embedded in consumer truth? Maybe our target audience today is twenty-one to twenty-four year-olds. Can I get this idea executed in the next twelve to eighteen to twenty-four months? My boss wants that done. Is it going to make us a bucket load of money?

You'll have a financial goal. And is it socially engaging? Is it going to get the twenty-one to twenty-four year-olds to talk about it on this social media? And all you do is you take each idea and the problem with ideas are they're horribly subjective, right? You like pink, I like blue, our boss likes yellow. It's a very good chance we'll be doing the yellow idea.

All you do is you go around and score the idea. Does it do a poor job, a good job, or an outstanding job of being aligned with our brand? It does a pretty good job. Is it going to make us a bucket load of money? Oh, hell yes. Is it socially engaging? It's fairly good.

Can I get it in the market the next eighteen to twenty-four months? Not a chance. Is it embedded in consumer truth? It does a fairly good job. And then with a different color for each of the last eight ideas you've got, at some point one idea will rise to the top as meeting your criteria the most, not the one you like the best.

By the way, the other thing that Branson always said was, "If it's not a three out of three of embedded in consumer truth and aligned with the Virgin brand, we must have the courage to throw it out." When we were bringing two new Disney cruise ships into market and we were bringing the big ones in, we had to decide where the old ones would go. Like any big corporation, that conversation takes too long. And oh, Dave's not here today. Oh, Sally's not here. Oh, we got to wait for Sally. No.

Or it comes to all the EVPs sitting in the room and go, "Do you know what? Last year I went to the Med, it was great." Oh, my wife loved the Alaska cruise." I don't give a toss. We use this tool. We're sixteen senior vice presidents of the Walt Disney Company.

We made a decision in fifty-nine minutes because one of them was, "Can I actually get a berth in the port of which we want in the next twelve months?" And if you can't, you shouldn't be doing it. And it's just great for cutting through all the nonsense. And again, the tours are designed to be simple, powerful, fun.

Guy Kawasaki:

So just as a little bit of realism here, if you looked at the top of the funnel when everything was “yes, and” and the bottom of the funnel, what percentage gets out and into reality?

Duncan Wardle:

That's very fair. So people often ask me what percentage of time they should spend in expansive versus reductive. And so everybody say, "Oh, 80 percent expansive." No, it's the opposite. It's 20 percent expansive, 80 percent reductive. The hard stuff is getting it done. Having ideas, like you said, you have hundreds a day. Getting them done through all the corporate approval processes, et cetera, et cetera, et cetera, that takes time. And that's where the innovation tools come in.

My favorite, as you could probably guess, is the one called What if? Why? Because it's about breaking the rules. So it was a marvelous tool, it was created by Walt Disney for the film, Fantasia in 1940. He wanted to pump mist into the theater and heat into the theater. And the theater owner said, "No, Walt. Too expensive. That's not the way we do it here." So Walt, step one, list the rules of your challenge.

So he just wrote down the rules of going to a movie theater. I must sit down. I must be quiet. It is dark. I must go to set time. I must watch the previews. I, Walt can't control the environment. Step one, list the rules. Step two, pick one. He chose the environment and he said, what if I could control the environment? Well, that wasn't audacious enough. The more audacious, outrageous and provocative your what if, the further out of your own river of thinking you'll jump.

So he said, "Okay, if I can't control the environment inside the theaters, what if I take my movies out of the theater?" Don't be daft Walt. They're two dimensional, they'll fall over. Well, what if I made them three-dimensional? How are you going to do that, Walt? What if I just had people dressed as princesses and cowboys and pirates?

People would be more immersed. Yeah, but you can't have Cinderella standing next to Jack Sparrow. People won't be immersed in her story. So he said, "Well, what if I put them in different theme lands?" Boom. What if I called it Disneyland?

Now for people watching, it's easy to say, "Oh, but I don't have the resources." So I'll give you another example, if I give you a big one, give you a small one. There was a very small company in Great Britain in the sixties that used to make glasses that we drink out of. They found too much breakage and not enough production when the glasses were being shipped and wrapped. So they went down to the shop floor, observed the industry, and wrote down the rules.

Twenty-six employees, conveyor belts, twelve glasses to a box, boxes made out of cardboard. Six on the top, six on the bottom. Glass is separated by corrugated cardboard. Glass is wrapped individually in newspaper, employees reading the newspaper. So somebody asked the somewhat provocative, outrageous waltz of questions and said, "What if we poke their eyes out?"

That's against the law and it's not very nice. But because they had the courage to ask it, somebody sitting next to them, the lady said, "Hang on a minute, why don't we just hire blind people?" So they did. Production up 26 percent, breakage down 42 percent. The British government gave a 50 percent salary subsidy for hiring people with disabilities. It's about listing the rules of the challenge, taking one and asking the most audacious what if question?

Guy Kawasaki:

Why didn't they just put newspapers in language that the people didn't read?

Duncan Wardle:

Ooh, see, there you are an amazing alpha again. Dude, nice one. Should have done it in Japanese.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, but I asked you a very specific question from the top of the funnel to the bottom.

Duncan Wardle:

That's fair.

Guy Kawasaki:

What's a percentage, one out of one hundred, twenty out of one hundred? What's the order of magnitude that get through this?

Duncan Wardle:

I don't think there's a set percentage. I would tell you one of the things that helped me get things done was persistence. I was like a bulldog and I wouldn't let go. If I believed in something long enough, I would go at it and go. I would drive my boss absolutely mental, and I wouldn't give up on it.

As I mentioned earlier on that the social video that we produced, which was the most successful social video we ever produced, I refused to go through the approval process. Why? Because the approval process will get everybody from brand strategy, touching everything and diluting the content completely.

And when we produce the video, somebody said, "Where's our logo?" I said, he's five foot two, he's got big black ears and everybody loves him. Get over yourself. Probably not the best. If you want somebody who stays inside the rule box, that's probably not me. But to the percentage of ideas that we came up with Disney, that came back out the other end, 5 percent maybe.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. Now, I think I know the answer to this, but how do you feel about these requirements of returning to the office? Do you think that returning to the office increases collaboration or returning to the office is going to kill the alpha state in most people?

Duncan Wardle:

Let's think about this for a moment. Who's making that decision? Oh, the boomers generation. Yeah, okay, great. Well done you. And what are you going to do? You're going to lose talent. Because the talented people can leave. They can get a job somewhere else.

If they don't need to be there, they don't need to be there. I'm sorry, I just vehemently disagree. As long as you get your job done, I don't care if you're standing on the moon. Here's the biggest challenge facing corporate America in the next five to ten years. Guess what? Generation Z doesn't want to work for you.

You already know it. It terrifies you. How would you stay relevant if this entire generation doesn't want to work for you? Why? Because you've been driven by quarterly results. They're driven by purpose. You think they'll bend to change to you? No, they won't. Just because you had to bend to change to your elders because you could only tell two people down the park. They can tell the world. So I was asked to give a talk to, let's just call it the largest tool manufacturer, about innovation and millennials.

So I didn't know anything about this generation in terms of how they reacted with tools. So I went down to Home Depot and Lowe's hung out in the aisle like some creepy dude, and I was just listening and watching at the point of purchase that we are taking this home. And I went back to this brand who is the largest manufacturer of tools in the United States of America.

I said, "Listen, this generation has never heard of your brand. They didn't mention you once. They didn't mention your products. The hammer, the chisel, the saw. They didn't even talk about the price, but they talked about what's important to them. We're going to remodel our dream kitchen, our dream bathroom, our dream apartment."

I said, "Your purpose, if you choose to create one, is you could be the brand who helps people build their dreams." You could see the finance guys going, "How quickly can we get this guy out of here?" I said, "Hang on a minute. If you are the brand who can help people build their dreams, could you be in banking? Yes. Finance? Yes. Engineering? Yes. Health? Yes. Education? Yes. Hospitality, sport."

You'd be in any line of it? "No. No, we make tools. We're really good at it. In fact, we're going to expand into Mexico and India. They have a great middle class, they will buy our tools."

Oh yeah? Okay, good luck with that. Have we seen the world of 3D printing recently? Right? India bypassed laptop computers and went to mobile phones. Generation Z will bypass tools and go to 3D printing. There's a chap now, I don't know if you saw the CBS special January last year, that's how much impact it had on me. Young guy in his thirties in Texas, building houses fully sustainable for 1,500 dollars in five days. And the first houses he gave to the homeless.

NASA have now employed him to print a landing pad on the moon from which he can print a printer from which he can build housing. And if we don't have purpose, I believe generation Z won't work for us. And if you don't have a new generation of employees, cast members, staff members, then I don't care how successful you are today, you're not going to be around ten years from now.

Guy Kawasaki:

I got to say that if I'm listening to this and I'm buying into this, my first question would be, I'm stuck in this company, it's full of “no, because” and my bosses and stuff. What do I do?

Duncan Wardle:

Leave. Now run to the door, run for the exit.

Guy Kawasaki:

Literally, you're saying leave?

Duncan Wardle:

Here's what I do with senior executives. I get them to do that “no, because” “yes, and” exercise. You can't tell people what to do. They have to do it for themselves. And so, people learn different ways. Some people will learn by seeing, some by doing, some by listening. And so I get them to do the “no, because” and the “yes, and” exercise because then they get, "Oh, I'm a no becauser."

And I tell them, "I know you have responsibilities. You are the CEO." Just remind yourselves, we are not green lighting this idea for execution today, we are merely green housing it together using “yes, and.” But I want to come back on those learning abilities for a moment. I can't get you to close your eyes, but we'll try it anyway. How many days are there in September?

Guy Kawasaki:

Thirty, I would guess.

Duncan Wardle:

Thirty? Okay, how did you know? How did you remember? How did you learn it? What did you just think of? What could you see with your metaphorically eyes closed? How did you know there were thirty days in September? Madisun, how did you know there were thirty days in September?

Madisun Nuismer:

Just remembering a calendar when I was younger.

Duncan Wardle:

A calendar. So Madisun can see it, okay. Guy, how did you remember it?

Guy Kawasaki:

I did it because I figured there's very few months with twenty-nine days. So it's thirty or thirty-one. So it's fifty:fifty, so just pick one and you'll be right half at a time.

Duncan Wardle:

30 percent of any audience will do this. Thirty days have September, blah, blah, blah, and November. All the rest, they are auditory learners. How do I know that? They just told me because how old were they when they learned the rhyme? Six. How do they remember it? Because they heard it. 40 percent of the audience would do what Madisun just did. They go, "Oh no, I could just see a calendar with a number thirty, the word September." They're your visual learners.

And then but you've never seen anybody do this. January, February, March, April, may, June, July, August. These are kinesthetic learners, right? They learn by doing. And when I decided to create a book, I said to the publisher, "It's not a book." He goes, "What do you mean it's not a book?" I said, "It's not a book. If it's a book, we failed." Why? Because when you see a book in an office, where is it?

It's on the coffee table, it's on the bookshelf. That's a waste of money, isn't it? So I decided, "Okay, what nonfiction book have I ever read where I could read one page today, put the rest of the book down, but know exactly what to do next?" I thought my mum's cookbook.

You want Shepherd's Pie, page sixty-seven. Cherry trifle, page forty-two. So the book is designed the same way. It says, "Have you ever been to the contents page?" It literally says, "Have you ever been to a brainstorm where nothing have happened? Go to page twelve. Work in a heavily regulated industry, go to page forty-two."

But it's also designed for our visual, kinesthetic and auditory learners. There's QR codes throughout, they're dynamic, so I can change them at any time. For the auditory learners, it's Spotify, but I'll change it to an audiobook over time. For the visual learners I'm now an animated character because I love doing things I haven't done before. So I went into a studio in LA and bounced around with some characters. And I teach you how to use the tools inside the Imagination board.

But for the kinesthetic learners, it is, one, I don't know if it's the first, but I haven't seen another one. It's the first ever fully integrated artificial intelligence book. So you can ask the book questions through the QR code on the back of the book and the book will answer you.

Now, here's the power of AI. So I thought, "Ooh, I live in the most litigious country in the planet, so careful now." So I thought, "Okay, I could just say, how do I use the tool on page sixty-seven?" Now who cares? I've just read the book. Why would I need that?

Now you can ask the book, "How do I use the tool on page sixty-seven to sell more orange pencils in the state of Pennsylvania on January the third next year?" The book will answer you. But I thought, "Ooh, but if they lose money on the orange pencils, are they going to sue me?" So it's like, "Here come the terms and conditions." I love doing things I haven't done before. That's the only thing that excites me. If I know how to do it, I get bored really easily.

So the book, it's a toolkit now. Now, I wanted to give it away for free. The publisher had slightly different ideas, still want to give it away free for students because these are tomorrow, and these are the people being told to stop asking why because there's only one right answer, don't forget to color between the lines. And they're identifying as not created by the time they leave university, and that's just sad.

Guy Kawasaki:

I read your book cover to cover and wow, there's so much in there.

Duncan Wardle:

Thirty bloody years, mate, tried to get into twelve pages. The editor had a field day. So the next book I want to write is called Rolling Back the Ears. It's all the fun stuff that happens behind the magic to make it happen like the day I stole the turkey from the President of the United States America on Thanksgiving Day or the day I sent my son's Buzz Lightyear into space for opening a Toy Story.

That's what I loved doing about Disney. What I loved the most was this Henry Ford quote, "Whether or not you think you can or think you can't, you're probably right." It was Disneyland's Fiftieth anniversary. The actual anniversary was over. The media were tired of hearing from us. I was like, "What else do the media have to cover even if they don't want to?"

Well, Mother's Day, Father's Day, Thanksgiving and Halloween, et cetera. I said, "Tell me about Thanksgiving." And this bloke said, "Well, the present pardons turkey." I said, "Hang on. That's the only turkey that doesn't get killed that year?" He goes, yeah. I said, "Wouldn't that make him the happiest turkey on Earth?" And everybody goes, "Oh, don't even go there, dude, because Disneyland is the happiest place on earth."

So I'm a great believer. You pick up the phone, you make your pitch. They could laugh, they could say no, they could put phone down, who cares? So I phoned the White House and I got through to the director of communications. I said, "Hey, what do you do with the turkey after the pardoning ceremony?" He says, "Oh, we give it to the National Turkey Federation." I was like, "Oh, didn't know we had one. Couldn't give me their number, could you?"

So I called the president of the National Turkey Federation, said, "What do you do with the turkeys after?" He said, "Oh, we just put them on petting zoo." I said, "Can I have them?" He goes, yeah. I was like, "Oh, aren't we supposed to negotiate or haggle?"

Then I found out more about turkeys than you could possibly want to know. turkeys when grown to a certain sites have heart attacks and die. I thought, "Oh, great. You want coverage?" The one turkey pardoned by the President of the United America is killed by a British PR guy in a stunt for Disney.

So in a moment of total and utter stupidity, Guy, we've all had those moments in our career which seemed like a good idea at the time. Well, I sent Pilgrim Mickey, the walk-around character and the parade music up to the pen, get the turkey kind of acclimatized, and then I phoned the National Turkey Federation.

I said, "You have told the White House we're taking the turkey, right?" He said, no. I said, "You have to because we're going to do the Super Bowl spot, 'Turkey One, you've just been pardoned by the President of the United States America. What will you do next?' 'Gobble gobble. I'm going to Disneyland.'"

So they phoned back and said, "No, the White House is in." I was like, "Oh, great." So then I get a call from our chairman. He said, "Duncan, I see you booked the corporate jet for the twenty-third of November from Washington DC to LA. Can you tell me the passenger manifest, please? I was like, "Well, Jay, I've got a couple of turkeys I need to move."

He goes, "Absolutely not." I said, "Jay, this is the second busiest travel day of the year. It's two days before Thanksgiving. If you cancel, we can't get this done. And the President says, we're doing it." He goes, "I don't care, we're not doing it."

Which I realized why afterwards, I wish he'd just told me. He said, "This would be his first request of the corporate jet from Bob, because Bob had just become CEO. And imagine being your first request, "I need the corporate jet." "What for?" "A couple of turkeys." So I'm now in my favorite meeting of my thirty years at Disney. Thirty-six people round the table. Very serious conversation. Animal welfare rights, corporate communications, operations, entertainment.

If the turkey dies halfway down Main Street, USA, will we run out of Shroud days or will we just look the other way and pretend it didn't happen? So then, God bless America, unbeknownst to any of us, the turkey that travels to the White House travels with a stunt double. This is what I loved about Disney. When you said, "Here's a problem," somebody went, "I got you." So this guy called Denny from entertainment pops up out of nowhere.

He goes, "Do you remember the old spy movies, the black and white ones?" I was like, "Denny, you really want to bring that up right now?" He goes "Yeah, yeah, yeah. Remember when the good guy's running away from the bad guy, as he hits the wall and the wall turns around, he's on the other side of it?" I said, yeah. He goes, "I'll build you one of those. We're going to put Turkey One out the front of the float, turkey two out the back. If Turkey One goes down, I've got your back." I said, "Oh, genius."

So now, when you think nothing else could possibly go wrong, it's a couple of weeks ago, bird flu hits the United States of America. I said, "Oh, for God's sake." So I phoned up the Director of Comms at United Airlines. I said, "Come on, we're going to have a bit of fun with this." And unbeknownst to us, they'd work with the Federal Aviation Authority.

So we walk into the airport, and this is back in 2005 now, where the airports used to go where the flights were dropped down, and it just came, instead of United Airlines 253, it just says Turkey One. I was like, "Oh my God."

So then we get on the plane, and they've got postcards in all the seats that says, "In honor of today's guests, Marshmallow and Yam, who have been pardoned by the President of United States of America, on their way to Disneyland, we will not be serving turkey sandwiches in today's flight. We'll be serving ham or cheese."

So now we get into the briefing room, and we did it for seven years. We did it with George Bush and President Obama. George Bush comes in, unbeknownst to any of us, his scriptwriter finds out where the turkeys are going, decides to have a bit of fun at our expense but nobody had told us.

And I'm in charge of public relations at the time. So George comes in, he goes, "This year, Marshmallow and Yam were a little bit nervous about going back to a place called Frying Pan Park." I was like, "Who the hell called it Frying Pan Park?"

He goes, "So this year the turkeys are going to Disneyland." I was like, "Oh, my God. The President of the United States of America." And he goes, "Not only that they were served the rest of their days at Disneyland." I was like, "Oh, my God. He said it twice." And then he wrapped up his speech, he said, "And not only that, they will serve as the grand marshals in Disneyland's Thanksgiving Day parade." I was like, "I could retire. This is the best day of my life."

So the head of entertainment for Disney Parks comes across the room looking really angry, very frustrated. I was like, "Dude, chill out. This is the best day of my life." He goes, "We don't have a Thanksgiving Day parade." I was like, "Oh, my God." He goes, "In order to build you two floats in a couple of days, it's going to cost you a couple of hundred thousand dollars." I said, "Well, Matt, I don't have any money. The President says, we're doing it, so over to you."

And two days later, God bless Matt, Marshmallow and Yam came down at the street of Main Street, USA Disneyland as grand marshals in Disneyland's Thanksgiving day parade. To me, it's the epitome. I love the Thomas Edison quote, "Whether or not you think you can or think you can't, you're probably right.”

Guy Kawasaki:

I dare you to try this again this November.

Duncan Wardle:

Don't go there. Do not. Do not go there.

Guy Kawasaki:

You and Elon with two turkeys. I can see that.

Duncan Wardle:

There's a joke there somewhere, but I'm not reaching for it.

Guy Kawasaki:

My last question for you is that you mentioned the concept of how to read your customer. Oh, I used the “C” word. How do you read your guest's mind? How do you read the mind of your guess?

Duncan Wardle:

Yeah, intuition. So if I were to ask people, have you ever stared at the back of the head of somebody you think looks totally hot and that person is a total stranger, they immediately turn around and look at you and you look away really quickly. Well, we've all done it. How did we know? How did they know? We have 120 billion neurons in this brain and 120 million neurons in this brain. The brain with which we as consumers and as business people, make a lot of our decisions when we say we went with our gut.

So what is the power of intuition in an AI-dominated world? We were tasked by Disneyland Paris to get more people to come more often, spend more money. Our data told us who could afford the brand, who affinity the brand had been shopping online. It was a ten out of ten of them coming this year. Well, they hadn't come. So my intuition told us our data was missing something. These people were either liars or procrastinators. So let's go find out.

So we went to go and live with one of twenty-six different families for a day. Now, going in hypotheses based on data and data alone was if we build it, they will come. Well, that's a 250 million dollar capital investments, Richie, so you better be right. So we went off to live with a series of different families.

Now, let me ask you a question, Guy, do you have children? Four of them. Okay, so I kind of need you to close your eyes, but not close your eyes. So picture the favorite photograph. It's in your house somewhere. It's a physical photograph. It's that favorite one of your children. It makes you smile every time you think of it. Which room is that favorite photograph in?

Guy Kawasaki:

It is a picture of me with my children. We're all in wetsuits. We're holding our surfboards. We just finished surfing.

Duncan Wardle:

And where were you that day? Where was the photograph taken?

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, there's two versions of that photo. One is in Waikiki and the other is in Santa Cruz. But let's say the Waikiki.

Duncan Wardle:

Okay, Waikiki one. Are you comfortable telling us your children's names?

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, of course. It's Nick, Noah. Nohemi and Nate.

Duncan Wardle:

Nick, Noah, Nohemi and Nate. How old were they the day the photograph was taken?

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, something like twenty-two, twenty, thirteen and eleven, something like that.

Duncan Wardle:

And how old are they today?

Guy Kawasaki:

They are thirty-two, thirty. I know. I'm going to get this wrong.

Duncan Wardle:

That's all good.

Guy Kawasaki:

Twenty-one and nineteen. I hope my wife doesn't listen to this.

Duncan Wardle:

Yeah. So give or take the photographs about twelve years old, the one that you just thought of?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Duncan Wardle:

Okay. So I asked the lady that I was living with, I said, "How old are your children?" The photograph looked like they were four or five. She goes, "Oh, no love. They're twenty-four and twenty-five." So I wrote it down. It's an individual clue.

It means nothing at the time. It's an individual data point. So when we got back together, we all had the same data point. When we asked the parent, when I asked you just now, when I asked her how old the children were, they turned out the picture was twenty years older in reality.

So my intuition was like, "Why is that? Why did you just pick the one that you just thought of?" Why people who are watching today or listening today who don't have children, close your eyes and think about that one in your parents' house with the dorky one of you from fifteen or twenty years ago where you look like a complete and utter dickhead.

But it's still there, isn't it? Yes, staring in the face every time you walk in. Why? Why is it still there? So I use the seven why's like a child, why, why, why, why, why. The insight for innovation comes on the fifth or sixth why, not the first or second why?

And all the mums talked about three moments in time through which parent and a child must cross. I've been through all three. I know where I was for all three. I knew when I was the day that my son, who was about nine, tears in his eyes, he said, "Are you Santa Claus?"

I was like, "Ooh." And what hurt was what was behind what he said. "I'm not your little boy anymore, daddy. I'm growing up." I know where I was when my daughter was thirteen, dropped my hand in public for the first time. It's a seminal moment between a father and a daughter. And I'm sure like me, you know exactly where you were when you had to say to your eldest goodbye for the very first time in their freshman year of college, and you had to turn around and walk away.

And so our going in hypothesis was, if we build it, they will come. But what we realized was despite what our data was telling us, there isn't a single mom on the planet that woke up this morning saying, "Oh, I wonder if Disneyland's got a new attraction this year."

But mom wakes up every morning as she does every day, worried about how quickly her children are growing up and how she wants to make special memories for them while they still believe, while they're still holding my hand, while they're still here. That's the segmented communication campaign.

Disneyland Paris, while Johnny still believes. Disneyland Paris, while Sarah will still hold your hand. Disneyland Paris while Dave is still here. Drove a 21 percent incremental attendance to the parks and turned a somewhat arrogant product-centric organization to a genuinely consumer-centric organization. It's now mandatory for every Disney executive to go sweep the streets of Disneyland one day or two days a year, and one day a year in the living room of one of our consumers using our intuition.

Guy Kawasaki:

And that happens to this day? That still happens?

Duncan Wardle:

Yeah. Oh God, yes. The thing is, when you get to my age, you get down on your knees to do some pin-trading with a small child, then you think, "Shit, I can't get back up again."

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, my. Duncan, man, it's seldom we have a podcast at such a pace. And this is like proverbial drinking out of a river. I know you use the concept of river of thinking in a negative way where you're stuck in that river, but this is drinking from a river of creativity and innovation. So I thank you for being on my podcast.

Duncan Wardle:

Thank you very much.

Guy Kawasaki:

And I'm going to look at Disneyland and Disney a whole different way, even more positive, if that's possible. And congratulations on your book again.

Duncan Wardle:

Thank you very much.

Guy Kawasaki:

Duncan's book's name is Imagination Emporium. And I cannot think of a book that is designed the way this one is, and with the colors and the illustrations. So as you would expect the book from Duncan Wardle to look like, it fulfills your every fantasy. So thank you very, very much, Duncan.

Duncan Wardle:

Well, thank you to you. And thank you, Madisun.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes, thank you. I'm going to thank the Remarkable People team, which is of course Madisun Nuismer, producer and co-author, Tessa Nuismer, researcher who dug up all the dirt on you for me. And there is my sound design engineers, which is Shannon Hernandez and Jeff Sieh.

So we are the Remarkable People team, and I find it hard to believe you're not a little bit more remarkable after listening to this episode and you're going to be more creative and innovative and change the world and empathetic and all that good stuff. And you're going to look at turkeys completely new ways. So thank you, Duncan. And until next time, Mahalo and Aloha from the Remarkable People team.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply