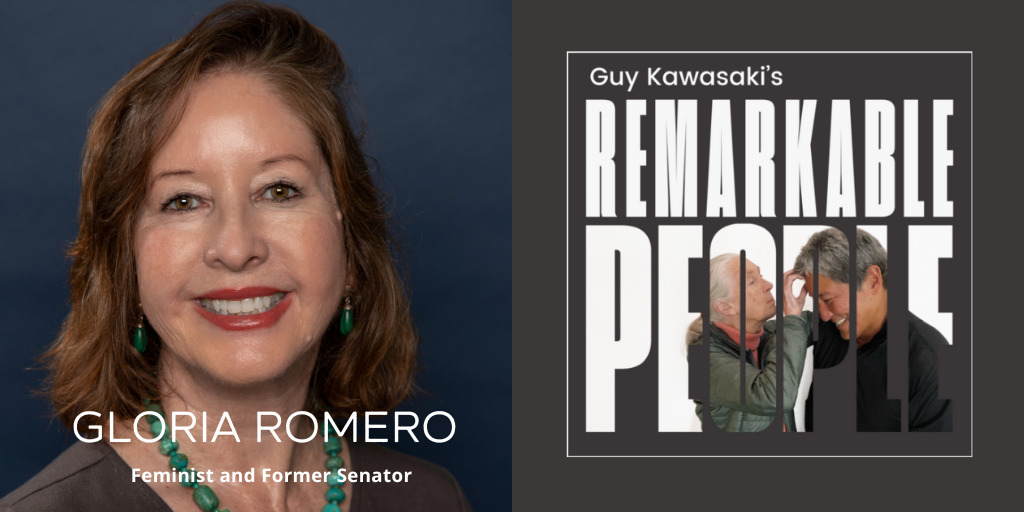

Gloria Romero is a Professor Emeritus of psychology at California State University and was the first woman ever to hold the position of Majority Leader of the California State Senate.

Gloria also served as chair of the Senate Budget and Fiscal Review Subcommittee on Education, making her a powerful voice on education policy in California.

She received both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees from California State University and has a Ph.D. in psychology from the University of California, Riverside.

Senator Romero recently released a new book, Just Not That Likable: The Price All Women Pay for Gender Bias, which focuses on sexism in politics and the workplace.

If you are a woman or parent of a girl, this episode is required listening. Her admonition to get over being liked is priceless. There is an extensive discussion of Ann Hopkins. If you’re not familiar with her, she was up for a partnership at Price Waterhouse in 1982.

Despite her outstanding qualifications, she was denied the promotion. She resigned and sued the firm for sex discrimination. This landmark case eventually reached the Supreme Court, and it upheld her claim in 1989 by a vote of 6 to 3.

Enjoy this interview with Gloria Romero!

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Gloria Romero:

Guy Kawasaki: I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is the Remarkable People podcast.

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

I am on a mission to make you remarkable.

Today's remarkable guest is Gloria Romero. She is the Professor Emeritus of Psychology at Cal State University and was the first woman ever to hold the position of Majority Leader of the California State Senate.

Gloria also served as the chair of the Senate Budget and Fiscal Review subcommittee on education, making her a powerful voice on education policy in California.

She received both her bachelor’s and master’s degree from California State University and has a Ph.D. in psychology from the University of California, Riverside.

Gloria recently released a new book, Just Not That Likable: The Price All Women Pay for Gender Bias.

It focuses on sexism and politics in the workplace. If you are a woman, or a parent of a girl, this episode is a required listening. Her recommendation to get over being liked is priceless.

There's an extensive discussion of someone named Ann Hopkins in this episode. If you're not familiar with her, she was up for a partnership at Price Waterhouse in 1982.

Despite her outstanding qualifications, she was denied the promotion. She resigned and sued the firm for sex discrimination. This landmark case eventually reached the Supreme Court, and it upheld her claim in 1989 by a vote of six to three.

I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People, and now here is the remarkable, Gloria Romero.

I want to get what I consider the 800-pound gorilla off the table. And I'm going to ask you this. And then after I ask you this, you may say, "Huh, screw you, Guy. I'm going to end this interview.”

What a caveat, huh? Would you explain to me your endorsement of Larry Elder? And let me explain why I'm asking you this because, on the surface, Larry Elder, influencer of Stephen Miller, says there was a fraud.

Trump is almost godsend. PMS stands for punish my spouse, denied the gender gap, and then he gets endorsed by Senator Gloria Romero. How does that work?

Gloria Romero:

Very easy. The biggest issue for me has always been education as a civil right, and education in California has been a disaster, especially for high poverty children of color, where we find 80 percent of African American kids not reading at grade level, not doing math computations.

How will they ever become an engineer? For Latino children it's about 70 percent of all prison inmates do not have a high school diploma.

So what I did was I basically called a general strike, and I said, "Look, ya basta. I'm tired." Year after year, governor after governor, legislature after legislature, we talk about the great promissory note, which is education, to access the American Dream, and we never get there.

So what I said is, "This is a governor who sends his children to private school. God bless him, but he denies the same for high-poverty parents. This is a governor who shuts down the schools in our communities, but his children continue going to school. This is a governor who tells everybody, including little children put that mask on, but his children run around maskless."

So I just finally said, "I'm tired." And so I knew it would cause a ripple, but I've said education is the big issue. So I don't agree with Larry Elder on climate change, or reproductive rights, or so many other issues.

But when half the state budget is going to education and my mother had a sixth-grade level of education, and I see those same faces of moms in East LA. And I think they're no different from my own mother. I just said I'm not going to continue.

So I've said it's a monkey wrench I'm throwing in. Let's talk about education because I am no longer just going to endorse and support anybody who just goes along with education as it is. So that was really it.

Anybody who knows me knows that education is my passion. It's what makes us equal. It lifts us out of poverty. It gives us a chance. And especially after COVID, that chance is diminishing.

So that's why. I knew it'd be controversial. I didn't realize it would be as big as... I mean, it just went international, but it speaks to why we've got to look at opportunities in education.

So that's why I endorse Larry Elder. He spoke about education from the point of view of African-American kids trapped in historically and chronically failing schools in South LA. And we can extend it to East LA and going forth to the Bay Area.

So it really was to say, we've got to address this. And Mr. Governor, with all due respect, you can't be so tight at the hip to the most powerful political force in California, the California Teachers Association, which has always blocked the kind of reforms that I believe we need to make schools better for all children.

Guy Kawasaki:

So is this sort of like an evangelical saying, "Listen, if you're anti-abortion, you can be a racist, sexist, crook pig, but I'm going to endorse you?"

Gloria Romero:

No, I wouldn't say it like that. But it does say that for me, I'm just tired of education being half the state budget, almost half the state budget in California, year after year, the failures.

And when I was in the legislature, I not only was the overseer of the education committee, but I also oversaw the prisons, the Prison Reform Committee. So I've been in virtually every prison in California for nothing I've done.

I don't want to edit that incorrectly, but I would see firsthand, who goes to the big house?

And then looking at basically the role of education and what we've done, and the perpetuation of teacher contracts that really facilitate what we call the dance of the lemons, where the neediest neighborhood schools don't get the caliber of teaching that we need. And so I just said, "I'm tired. I'm not going to go for a governor who will shut down."

So I did let people know, "Look, education is what I'm driving this on. I want us to have a debate about education."

So be prepared because I'm back. I'm going to be supporting its education savings accounts for California. This would be the first time we would have them in California. I'm working with get ready, Ric Grenell, the Head of Fix California.

And to me, you will see that I am really very nonpartisan when it comes to education. Because when I see the parents out there, parents bring their kids to schools, and they don't say, “My child's a Democrat. My child's progressive. My child's a Republican. My child is a peace and free.”

My child is my child, and I want the best for them.

So, anybody who will tell you about my days in Sacramento, they will say that I'm actually from the left, that I'm progressive, but that I listened, I worked with Democratic and Republican governors.

It was Arnold Schwarzenegger, who actually was governor for most of the time that I was there. We did prison reform, and we did school reform together.

So I worked across the aisle with people. That's why I actually empathize and am enjoying Joe Manchin today because I do think that even when we disagree, it's not about name-calling.

It really is saying this is the issue, let's make it better and park our labels at the door, and in a very politically partisan world, it does create surprise. And I think that's a good thing.

Guy Kawasaki:

One more question on this topic, because it fascinates me. So what happens if you endorse Larry Elder? Larry Elder wins. Larry Elder as governor, suppresses voting, no more mailing ballots. Makes fewer polling places where black and brown people vote.

So California flips from blue to red. When it flips from blue to red, Donald Trump, Ivana Trump, they all get elected. Now they're president.

So the Republicans truly control the country even more. Uh oh, I don't think that they're going to be supporting education for brown and black people if they come to power.

So wasn't there a humongous danger when you did that?

Gloria Romero:

I don't believe so. And on the voting issue, I'm going to say with all due respect scare tactic, we have a legislature that is one party in California, it's Democrat, and I'm a Democrat, but I look at it, and there is no way you would have a change basically in how we do voting in California via the legislative process. Every state elected official is a Democrat, including the Secretary of State, for example.

So the scenario of suppression change, et cetera, we can't have by theory that occurs overall. So I wouldn't foresee that happening overall. And so, I don't think that it was one about what would happen if Larry Elder were governor.

I really think that even as a governor, and Jerry Brown or Arnold Schwarzenegger will tell you, you still have to negotiate with the legislature.

There still are the people representing us, et cetera. If anything, what I find is actually now, during the era of COVID, the governor has assumed extraordinary powers, but the declaration of a health emergency that's been recognized nationally, and the legislature has largely been very silent in all of this. It has not always been that way.

So I think there is sort of the going along with Gavin Newsom, but I will say frankly before I endorsed Larry Elder, I was hoping that a Democrat would run. That was my first hope.

And I was hoping actually that he had run before Antonio Villaraigosa would've run. Again, he ran against Gavin the last time, but I have been in party leadership in the state legislature. I know how it works.

And basically, they told people, "Sit down, shut up. Your political careers will be ruined." Kind of like cruise booths the month. If you can go back and remember when that recall happened. So there is a great deal of retaliation.

People say, "Gloria, why don't you run for governor?" I don't believe in flattery, and it's shows me the money. It’s a multimillion-dollar campaign. And Gavin would've had all of the status quo.

So I looked for who else can we get, et cetera. Antonio, you've got some strong backing. I'm going to go out on a limb and say, I know that he looked at it. He considered it.

And I can't speak to why he ultimately did not go, but he backed off. And I think partly it's the sense of retribution. And that's something that, whether one's Republican or Democrat, we really shouldn't be proud of.

So I looked at that, and then I thought, if the party is going to shut people down, remember the secretary of state tried to disqualify him and all this stuff. And see, I don't believe in that. I just think you know what? Play fair, remember he didn't get this in and bad in and-

Guy Kawasaki:

Reforms?

Gloria Romero:

Exactly. And I don't play that game. So I gave it a shot. Is there going to be a Democrat? Okay. No. Then I'm going to look at the column. There's no Democrat. I'm going to look to see which Republican, Larry Elder.

I wasn't going to go with John Cox or some of the other ones. I just didn't care for their position overall. But to me, Larry Elder, what everyone thinks about him. And he is a genuinely nice person.

He speaks very eloquently about black and brown kids, especially in California. And that was where I said, "I want to throw a monkey wrench into the system and say, "Hey look, folks, we got six and a half million children in California. It's more of a public works program than a public education program. And our kids are just being left behind. And when we get left behind, we don't go to college. We can't think of being architects and engineers. Our families, we go to prison."

That's what ends up. We become alliterate and go to prison, and we get locked in menial positions." And I've just said, "I'm going to speak up. And I want people to think about it."

So that was really why. And I stand by it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, can I ask you a couple of more political questions? And then I promise you we'll get to your book.

Gloria Romero:

Like they say, in politics, you have to have a thick skin. And for women, it's got to be even thicker because they will come after us even more so.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, my father, when I was growing up, was a State Senator in Hawaii. I think he was Vice President of the Senate. And then he was the second or third highest person in the city government for Frank Fasi.

So I come from a political family. So I know that's why I'll never get into politics, but that's another decision.

So you've mentioned Joe Manchin a few times, and I just want to know why you mentioned him in such a positive light because it seems to me that he's standing in the way of a lot of reform and change and et cetera, et cetera, that most Democrats would find highly desirable.

Gloria Romero:

I always tell people, look, I got into politics with JFK, Bobby Kennedy. That was my motivation. But these were like, "Oh my God, somebody was speaking up for the little people, blah, blah, blah."

So really, sort of the JFK, I'm moving forward. My father worked the railroads, and so he always thought every politician was a crook, by the way. So when I first got elected, he said, "Well, except for you."

So I kind of came out of it, like really what fits the working class, the little guy. I do think there's so much corruption in politics, there's big money, et cetera.

So fast forward from that background, I'm not supportive of further debt. I do think that it's really looking at the debt. I don't believe in paying off student debt. I tweeted to AOC pay your own debt. She's got 17,000. I said, "You know what? Pay your own debt." Didn't respond.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's probably how much that dress costs, but okay keep going.

Gloria Romero:

Yeah, exactly. So I look at it, and I tell because everybody says, "Gloria, why don't you leave the democratic party?" But I go, "I'm not a Republican."

If anything, maybe I'd be independent these days. I tell people, like so many others, "I'm not leaving the party. The party has left me," and I hear that over and over. And even if you look at national polling, there is a great deal of numbers who don't believe in the Build Back Better bill. The first one went through, okay. Infrastructure, et cetera. I am very and more so over the years, become much more averse to great debt.

And so I do think that in writing the bill, there are ways where they could have disentangled it and put one program that would last for, if you want to last for ten years, then put it for ten years. But I know how these bills are written.

Basically, you put the news, the camel's head, under the tent, and once they're in the tent, you never then undo a program.

It becomes really difficult, and I've never met Joe Manchin. I've never contributed to him, but I've watched him then Kyrsten Sinema, by the way, from Arizona. She has stood up as well. I like the independence.

What you'll find about me is I the just don't go along with everyone. Go ahead and hold your grounds. Speak up. Even if the world is... Because think about this.

When I was in Sacramento fighting for education and prison reform at the same time, I had to deal with two of the most powerful unions, political forces in California, the Teachers Union, and the Prison Guards Union.

And they're like, "Gloria; you're taking them on at the same time." And I just thought, 'That's what I'm here to do. This is what I believe in." So it never got to me.

So with Manchin and looking at it, there's a lot of discussions. I think overall, people don't feel strongly about the BBB. I do think they could have taken it apart. I do think you can negotiate it. I really do believe you got to get to fifty votes. You can't just say we got forty-eight Democrats. You two sign-on.

So I like that independence in him and Kyrsten Sinema. I'm a bit of a troublemaker in my own party.

Guy Kawasaki:

My head is exploding, but okay. I just want you to know that I am the Chief Evangelist of a company named Canva. And it does online graphic design, and it's doing extremely well. And I want to go on the record to tell you that my boss is a woman who is half my age.

So I'm breaking two barriers right there, and I'm proud of it. And so I want to put that out there. Question number one, getting into gender bias and your book, is, do you think that if Elizabeth Holmes was a man, she would be in as much trouble?

Gloria Romero:

I don't know all the details with Elizabeth Holmes. Okay. For purposes of full disclosure. So I've been just following it from afar.

I think women are held to a tougher standard because of the expectations that we aren't really as equal in terms of being a leader. And I say that because, in part, if we look at the numbers, numbers tell a story to a great extent. They're very lopsided.

In my book, I talk about how some of the reports say if we ever get to gender parity and not that parity is the answer. I don't want to say there's a quota system because I don't believe that either that you have to have fifty-fifty, but when we look at the discrepancy between the number of women who actually lead Fortune 500 companies, versus the number of women who graduate with MBAs, but then stalled in their careers, we take a look at what are the expectations for women and how much shorter fuse do we have when we believe that women mess up. And so we are more harsh with women.

So to go back to your quest, I would say it would be a different story. We'd be seeing a different record overall because of the expectations of success and failure that we still have, especially for leaders in our society.

Guy Kawasaki:

I've done about 120 of these interviews. And I would say probably 60 percent women. I am very cognizant of at least equality, or the majority of my interviews being women from Jane Goodall, Margaret Atwood, Angela Duckworth, you name it, Arianna Huffington.

And I'll tell you three things that I've observed with this podcast.

First, when I do a recording, and you can see it here, we both see each other, and only women make a comment like, "Oh, are you recording video too because I'm not really put together enough for video."

No man has ever said that. Observation number one.

Observation number two is I've interviewed many female CEOs. And one of the consistent issues they bring up is they had to get over the imposter syndrome that they didn't deserve to be on the board of directors of Verizon or the CEO or get this award of this promotion. No man has ever said, "Oh, I had to get over the imposter syndrome."

My third observation. No one, man or woman, has said that their father was the major influence. Everyone who brings up their parents says, "My mother fostered my independence, fostered my education, fostered my dreams and aspirations." No one has said, "Father”, do you have any comments about my observations?

Gloria Romero:

I think they're very accurate. I'd say said probably for at least in my case, on the mother-father situation.

First of all, let me say that. If you'll notice, I didn't ask you if we were being videoed. I did read my notes. I had very good preparation, and I did read them.

But also, I thought this is me. I thought I'm not putting on a suit. I've got a scarf on, et cetera. My daughter said, "Put mascara." I had passed the days of mascara.

So I thought I'm okay but also remember I'm at home right now, but in the workforce on the stage, et cetera, you're absolutely right. We look at women. We observe women. We will make critiques of women, especially leadership, in terms of we didn't dye our hair. We've got the spot of gray. Oh, she needs Botox. She doesn't smile enough. What about her clothing?

I had mentioned Senator Sinema before, who, again, I've never met. She's from Arizona. I don't know her. I don't contribute to campaigns outside of California.

But I recall just recently they were criticizing her clothing, her outfits, her fashion choice, et cetera. And that is what women get. I'm not talking about. We have to agree with them politically.

But when Carly Fiorina was running and was running for the presidency, it was about her face. What did she look like? Did she have to have a facelift? She also acknowledges that her looks were something that people raised much more, so yes, women still are looked at in terms of how we appear, how we dress.

So I can see that in doing the podcasts and others, we get a little bit more attention. I mentioned in the book as well. We talk about ageism, and there's a whole section that talks about Hollywood, et cetera, Geena Davis, and some of the fabulous work that she has done at USC and her institute, looking at how women age in Hollywood, they talked about turning twenty-five, thirty when you're past fifty, forget it.

Your looks have gone. So therefore, you're not as popular anymore. It's the same thing in the political arena. In the corporate arena, there is attention overall.

Then you had asked about the father and the mother about both of mine, for example. Both my father and mother played a very important role.

I mentioned my mother all the time on education, which is really what has moved me forever. And she really made it possible for me to understand what a parent will do. And all she did was show up. She would clear the table. We didn't have desks. I mean six kids. We were a working-class family. She would give me space to do homework.

My mother played a fundamental role, but my father was really the one who I followed. He took me to union meetings. He took me to community meetings. He talked, and I'd listened in those days, I didn't talk. I listened.

So a lot of what I say now, I feel like his consciousness is coming through me. So both of mine are actually very important in my life as mentors.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's true for me. My father was very important in my life, but it was just an observation. No one's ever mentioned her father except you.

How do you think Ann Hopkins would do with this Supreme Court?

Gloria Romero:

Oh, first of all. And I'm going to say. I didn't know who Ann Hopkins was.

Guy Kawasaki:

I didn't either until I read your book.

Gloria Romero:

I mean, honestly, and let me tell you, you probably know as well. I was a university professor. In fact, I have a nice title of Professor Emeritus now because I retired from the university too.

I taught for twenty years in psychology, women's studies, gender studies, sex and discrimination, blah, blah, blah. And I would always touch on the issue of women in the workplace discrimination.

We mostly talk about overt discrimination. Like when women don't get the same pay for the same work or basically saying, we're dealing with something very violative, we didn't really go into looking at stereotyping.

So when I started doing the research and looking at this, I was really stunned to learn about Ann Hopkins, and I think, "Oh my gosh, I want people to know her name."

I call her the Rosa Parks, really of the gender discrimination of the gender bias movement. And I hope if nothing comes out of this book that people understand and know who she was and what she did.

So fast forward to this court. How would she do today? I can say I don't know what would happen with the court overall if the case was brought up today, but we certainly talk about precedence. We certainly take a look at what has happened overall.

But when we think about the court that existed when she came up, that wasn't exactly a liberal court either. I'd have to study the history of everybody who was on the court, et cetera, what their leanings were, but that was 1989 when the court ruled. And it wasn't as though it was a great leftist coalition or anything like that on the court.

Guy Kawasaki:

No kidding.

Gloria Romero:

So I suspect that with more women on the court today, I think it was so overt that you have basically been told that you can discriminate on the basis of stereotypes' likability. I would like to think that this court today, if they met Ann Hopkins for the first time, would rule in the same way.

Guy Kawasaki:

How do you think gender bias has changed since Ann Hopkins case?

Gloria Romero:

Sadly, I don't think it's changed enough, and that's what is shocking to me. But in the book, I point out with the number of cases that are filed, and the good thing is that we're filing because I really argue that there are choices, and some women decide to go to court, but to take it to trial, depends on their resources overall.

Others might go into arbitration depending on their employment. Some might just file. Some might do a blog. Some might write a book. We have all these different examples of what women have done based upon their own personal experiences.

But what is important is that women are documenting today, and that's what we've got to do. It can be scary. It can be a frightening process. I have filed a claim of gender bias as well. And all I can legally say is the matter has been resolved, but it's important for us.

So, where are we today? We still look at the statistics, and the statistics still show that there's this big mismatch, this gap between women who get to the C-suite, the highest levels of authority, including in the political arena.

And yet we don't stay there, or we get in such few numbers. And then when you start examining what's happening, and you start taking a look at even the psychology and sociology studies that still show today that men and women readily say, "They'd rather work for a male boss than a female boss."

Or we still see the results of psychological studies that show even if it's the same resume for a male and a female, a hypothetical male or female leader that we tend to like the male leader, but we don't like that uppity abrasive unlikeable woman who's trying to act like a man.

In the political arena again, irrespective of people's politics, thinking back, Hillary Clinton, Amy Klobuchar, Elizabeth Warren, Kamala Harris, they were all described as “Mean, nasty, aggressive. They're angry women.”

On the other hand, there's Bernie Sanders, who I like as well, but there's Bernie Sanders. And he's always seemed to be yelling at somebody, but everybody loved him. He was affable.

So you think that Elizabeth Warren can't scowl because she's angry and she's mean, but there's Bernie. And we expect him to yell at us, and then we love him because, oh my God, he's just the little socialist with four homes. And so you look at that gender bias, and it hasn't changed.

Guy Kawasaki:

Did the liberal press condemn Sarah Palin in the same ways?

Gloria Romero:

Yes. Somebody asked me about this, and I hadn't included her because I was talking about the presidency, but we look at the vice presidency to a large extent. She was vilified as well in terms of how she presented herself as a woman. I think it was even a little bit harder for her because she's a conservative woman with a more liberal press, but she was mocked.

And it would be interesting to go back and take a look at women just sitting down with women. That's why I said, forget the political persuasion. If women who have run for office would sit down with each other and just go around in a circle and say, "Hey, this happened to me.” I would bet. No matter how we would vote on any piece of legislation, we would all say, oh yeah, that happened to me. You could host that.

Guy Kawasaki:

So you touched on it very briefly, but I would like your comments about the concept of nondisclosure agreements.

Gloria Romero:

Somebody you might want to interview is Senator Connie Leyva, here from California. She has carried legislation on curbing and curtailing the use of nondisclosure agreements. So there are pros and cons overall.

I think there are more cons than there are pros to this. And especially when something happens with taxpayer dollars, say in a school district or looking in city government, for example, that's paid with taxpayer dollars. I believe the people have a right to know what's happening.

So what happens with NDAs is that oftentimes men and women, we come into the workforce, we start day one. We're given the contract and buried in there is, you go to arbitration and blah, blah, blah.

And most of us never think we will ever get to a situation where we might need that. So that's step number one. There has to be a lot of discussions when we're signing the employment contract. What rights are there? And can we begin to do reforms there that will not mandate arbitration from the get-go because that's a big problem right away?

But having gone through that, then you could say at the end of it, what do I do? I can go to trial. And we saw, for example, Ellen Powell, when she went to trial, and she lost her case, great personal expense, et cetera, money, resources, et cetera. It can be a great deal of turmoil. And do you have the economic resources? A lot of women don't.

So going through arbitration and a settlement might be an easier way. I'm not saying one way is better than the other, but I do believe we have to look reforms and NDAs because what it does essentially is it says at the end of the line, basically, you can't talk about it. You cannot say anything.

And it's almost as though if we think about the experience of being raped, you've been raped, and then you can't talk about it with anybody. You're just supposed to settle with your assailant. Maybe you can talk about it with your spouse, that's it. But you can't share the story. You have to basically have it stifled.

I'm a psychologist by training, and that's not good mental health, but we're forced into that. Women and men as well, to anybody who goes through an NDA, that's one of the basics of contingencies. You sign this, you do this, or else go to trial and then years and how much money, et cetera.

So there are choices, and I'm grateful that Senator Leyva has begun to make some changes. And she's going back a second round. There was no more bills that would gone to the governor. So basically, it's not over because you can always find the loopholes.

So I don't like NDAs. I do think that we have to reexamine them, and there are ways in which we can do it because nobody should ever be silenced.

Guy Kawasaki:

So on the flip side of this, how about this requirement that boards of directors has to have a woman on it.

Gloria Romero:

That's actually, for the purpose of full disclosure, my former roommate, Hannah-Beth Jackson, who we started the assembly together. And she was my former roommate. We always talked about gender issues as well. She's the one who actually wrote that law being challenged, et cetera.

Once again, I don't believe in quotas. I don't believe in “You have to have the mandates here and there”, but we do have to close gaps. What are the processes by closing them because of the discrepancy once again? How do we ever get to some sense of, and I don't want to say parody, but representation?

So overall, I liked her bill. I liked the law. I do think that having women on boards makes a difference. But as I also write and point out, it's not always having women on boards. I do believe there really is no such thing as the sisterhood because a woman will stab you in the back as easily as somebody else.

And so there's a whole bunch of other issues, and you can have men as strong allies as well. But I do think that women's voices mattered. And when we see the lack of representation at the end of the day, what is almost suggested to me is do the right thing, and then you don't need legislation because all legislation is really trying to fix something that should have been fixed.

So I always felt like in writing pieces of legislation, I shouldn't have to write this, but I'm going to, because duh, as my daughter used to say, when she was little, “You guys should have done this a long time ago, and we should recognize the diversity of California”, but it takes somebody saying, "I'm going to throw this bill at you to point out the vacuums that are there. And now we battle it out in court."

Guy Kawasaki:

What is it about men that they cannot deal with strong women?

Gloria Romero:

People are resistant to strong women. And I go back to looking at how are we socialized? Think about it, right from the get-go.

And I tell people that the most important three words in our lives, the most important pronouncement, it's not I love you. It's really. It's a boy. It's a girl. And we start setting up right from the beginning, the choice of a greeting card. Do we paint the nursery pink or blue? And even in the days of all the wokeism, we still do that.

When I used to teach at the university, one of my favorite lectures was we would go to the then Toys "R" Us as a field trip, and they would just have their eyes open. And as they saw what I call, there's the pink section and the blue section, the boys and the girls, and they're never labeled, but you can see it. Where is everything placed?

And you start finding that girls are encouraged to be nurturing, to be soft, to be motherly, all of the baby doll products, the nursery staff, the cleaning staff. It's all in the pink section. And then the Barbie dolls and all of that, we know we have to look attractive and catch our man and all that.

In the boys' sector, you're going to find G.I. Joe, the action figures, the trucks, and all of that. And people ask about what about Ken? Ken is not an action figure. Ken is arm candy for Barbie. That's who we're supposed to catch and have on our arms as we wear our heels, et cetera.

So we're socialized. And part of it is learning how are we supposed to behave sugar and spice and everything nice. And these studies have been done that show that parents, right from the beginning, start treating their infant boy or infant girl child in very different ways.

We cuddle and hold the little girl. But we think of the little boy as, "Oh, you're a little independent. My little tiger, my little man."

So we start doing that, and we start making different attribution towards them.

So it starts early on, it intensifies high school, college. By the time we are adults, basically, we look at men and say, "He's supposed to be domineering. He's supposed to be strong. He's supposed to stand up and speak."

You might notice I use my hands a lot. Believe it or not. I have actually been reprimanded for using my hands, and they've told me basically sit down and shut up. They've told me all I can say is in my career. I have heard the, will you stand when you... It's like standing while leading but speaking while leading. You use your hands. You might intimidate people.

Guy Kawasaki:

People really said this to you? Are these your advisors, your trusted inner circle? Who would say that to you?

Gloria Romero:

This is what I've been told overall, and looking at why it motivated me to write the book. So I have experienced, but believe me, I spoke to other women as well. And they said, "Oh yeah, that happened to me."

And basically, they're telling us, "Sit down, shut up." Like basically. But in the old days, we used to wear the... What were they call all those little things that held you in when you couldn't breathe?

Guy Kawasaki:

Corsets.

Gloria Romero:

Corsets. Yes. It's the equivalent of that in terms of leadership.

But basically, we tell women, "You're not supposed to be noticed. You're not supposed to be strong." And when you speak up, then you're intimidating people. And this has occurred in my lifetime, in my career recently.

And so when you talked about gender bias, what would Ann Hopkins see today? Maybe the overt stuff. I mean, we're still battling at equal pay for equal work, but this is the subtlety of stuff where we still allow the stereotype.

We expect men to lead, and we like him because we expect it. But when a woman leads, she might be competent, but then we don't like her because she has to be abrasive. She might have to raise her voice.

I talk about communication styles. We allow men to be direct and to lead with directness. For women, think about the old adage, let him think it was his idea, or we're supposed to avert our eyes.

In doing the research for the book, I literally found some advice to women in leadership or contemplating executive careers, basically telling us to change ourselves.

Like maybe it shouldn't be so loud. Maybe we should curb our voice. Maybe we shouldn't use our hands. And I just said, "No, we don't do that to men." I tell women, "Just get over being liked." It's not that important.

Don't worry about being liked because we will never be liked in the same way as a male executive because the expectations are different. He is supposed to be dominant and strong in leadership and charisma. She's still supposed to be nurturing, so she can either be a good leader but then not a very good woman.

I mentioned the prime minister from... She was the first female prime minister from Canada. She talked about it, and she said, basically, she was doing her job, but doing her job, that mean she would be a good leader, but she wouldn't be liked, but if she didn't lead the way that she led, then she would be an ineffective leader, and that's a double bind.

That's what they call the Goldilocks Syndrome. Where basically, what do we do? Why can't a woman... I'm thinking about my fair lady now, but why can't a woman be who we are and be liked for who we are, but socialization, et cetera. And it's not just the US, it's international.

Margaret Thatcher, again, to end Indira Gandhi, Angela Merkel, all of them have shared stories, and they're there, they're successful but liked. It's probably not a word we put for them.

Guy Kawasaki:

What if you have to be liked to get elected in order to be in a position where you don't need to be liked? Isn't that Hillary Clinton? Didn't I just describe what happened to Hillary?

Gloria Romero:

And see, we take a look at what happened to Hillary, and there's lots of issues. People can take a look at politics overall. What did they say? There was Benghazi, the emails, etcetera.

But when we looked at it overall, the voters still looked at Hillary and said and she was competent. She was capable. She was secretary of state, Senator.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, my Lord. Yes. We had the most competent candidate going up against the least competent candidate, and the least competent candidate won.

Gloria Romero:

And again, till you take a look at male and female, and I don't know that we liked him either, but we certainly didn't like Hillary. If we were talking about how we're described. Women, don't just laugh. They cackle.

That's the thing with Kamala Harris, and Kamala Harris has made some real serious mistakes. I will criticize elected officials overall. I think she's made some very serious mistakes and is not taking as credible, but then we add onto it.

And when we describe her, we say, "Oh, that cackle," that's something that, if you think about it, we learned that a cackle is something a witch does. And a witch is something that women are called, and it rhymes with that other word that starts with a B.

Then Bernie Sanders doesn't cackle, Schumer doesn't cackle, Donald Trump doesn't cackle. They might laugh, but women or women cackle. And it really because when we become genderized and put down in the process.

So Hilary cackled. We made fun of her hair, her weight, what she looked like. We have a very different set of attributes.

It's almost as though we have a leader, can we like that leader if they are women and the women are stronger? They're not these nurturing people that we expect women to typically be.

No. Women are supposed to love you and care for you and be nice. And again, here I am talking with my hands. That's what gets me into trouble.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, well, how are we going to break this cycle?

Gloria Romero:

Absolutely. Part of breaking the cycle is talking about it because, like I said, too, I thought I knew all this stuff.

And here I was, the majority leader of California, and I would see things overall, but I had never heard of Ann Hopkins.

So we see the overt discrimination, but it's what we don't see that we just don't talk about.

And I think the important thing is we have to name it. We have to own it. We have to start talking about, and the book's really written for women, but I hope men will read it and if they're experiencing issues in their workplace to do the same thing. We have to document it, do not be afraid. I also think too, that we can't just expect women to be the gender police.

We've got to back up. We've got to also have important voices there in the mix.

I point out as well don't expect all women to be supportive, but this so-called sisterhood doesn't necessarily exist. So it's important, though, to document, to look at the records from corporations or school districts.

Whatever the workforce is, we should ask for the records on the filing of claims and the payouts overall and get to as much information as we can.

So there has to be the discussion and then the NDAs, the legal piece of it. If we can begin to eliminate that as well, so that we can talk about it and know what's going, because if corporations right from the get-go, or school districts, whatever it may be, know that this is public and there's transparency, we're less willing to hide it.

But ultimately, we have to take a look at how do we socialize ourselves? What do we allow in men and women? What do we expect from men and women? Even as something as simple as jury duty as well, we oftentimes anticipate that it will be the male leader rather than the female.

When men and women say pretty much equally, "I'd rather work for a male boss than a female boss." Why? And so we have those attributes overall, and then looking at the boards because boards are very important.

So all of these can be done, but if we don't do it, as a Catalyst just pointed out, or Sheryl Sandberg's organization lean in with their women in the workplace, we're basically looking at another project 400 years before we get any parody at all in work. And at that point, forget it Ann Hopkins rolling over in her grave saying, "I should have just gone to charm school," but that is the thing too.

I really urge women to get over the need to be liked that it's, and in an era of social media tweets, "Oh my God, how many people liked me," or Facebook or Instagram, that's sort of the messaging.

So we have to really stop and think about “I want to be productive.”

I also think in how we get over it as well is in how we do employee evaluations. And so there is that thing called team building. And that all sounds good on paper, but once you start looking into it, it still is relational, and it becomes attributional. Do I like somebody?

I actually argue that we need objective criteria, basically, come up with the metric of what should I do? Is there a dollar amount that I need to bring in? What about grants or succeeding on projects to the end on time, et cetera.

So having a very objective criteria that need to be negotiated right from the get-go when you're first employed. Because if we do the relational stuff, like teamwork, teamwork will fall apart real fast.

And it sounds good, but it doesn't work for women, especially as we climb the corporate ladder, because then all of a sudden, oh, we didn't like her because she was a bitch. And she said something with her hands again, which I thought is getting me into trouble with my hands.

Guy Kawasaki:

This is audio-only. Don't worry.

Gloria Romero:

So there's a lot that we can do. We just have to start doing it and documenting it and basically bringing it out of the closet. Giving it a label. Having people learn the Ann Hopkins story, which is one of the most beautiful stories.

And to know that here is this intelligent woman who herself said she was one of the first persons. She said, "Look, I'm the first one to say I'm not likable, but that's not the point here. I'm here to do my job and do it well." And she did it well, but they told her you're macho, and you ride a motorcycle, and you wear a jacket, and you smoke, and you swear, and your hair's not pretty. And they literally told her, "Go to charm school," and Ann Hopkins said, "No."

Guy Kawasaki:

So we know what adults should do. What's your advice to parents as they raise children?

Gloria Romero:

Parents are very important because we really are the first teachers. We're influential. And I'm not saying go and throw out all the pink clothing and the blue clothing. I'm not saying that, but we need to be cognizant of it.

How do we treat our boy and girl infants? It is important to allow boys to encourage boys, to have their parenting fun and to play with dolls and learn to clean and all of that, that men are supposed to learn to do when they grow up anyway.

So I think parents are very important for girls as well, too, to allow them to be independent and to get dirty and not as necessarily be sugar and spice and everything night.

So parents are very important. Parents oftentimes are the first blocker. If you ever used to go into Toys "R" Us, I used to go in on Saturdays. I would love doing it. And I would kind of follow people around, and you would literally hear parents, "Oh no, this is in your section. Let's get you out of here." But we have to have the conversation.

The classroom, educators, there is something to understanding gender bias and teaching and having ourselves recognize how we relate to somebody or how we punish somebody or how we devalue somebody because of the tone of voice, or if they speak up or how they act that defies a stereotype that we somewhat gave to what we expect men and women to be like.

So there's a lot to do, but parents are key.

Guy Kawasaki:

I have one more story for you. A few months ago, I interviewed the former chief of staff of Jeff Bezos of Amazon. And he told me a story that one part of Amazon had just a woeful lack of women management.

And so what they did is they instituted a policy where every woman who applied got a first-round interview, every man who applied was screened. So this meant that there were a lot more women candidates who got to the next round, and this really impacted their hiring.

So do you think that is a band-aid? Do you think that's clever? Do you think that there's some wisdom there?

Gloria Romero:

I think it can be all of the above. I would also say too if I were a male, I might say, "Wait a minute, that's discriminatory as well, in terms of why is there a different step?"

I'm trying to be cognizant of all of this because I think in this battle, we want to have men and women brought along and be given opportunities.

One of the recommendations that's actually come out is rather than doing something like that is, maybe saying, "Let's do blind auditions" and basically have the resume so I can look at the resume and to understand this is who and how and what the credentials are.

In the world of music, orchestras, for example, have oftentimes been very male, very few women, and some began to see changes when they said, "We're going to do blind auditions."

So you couldn't see who was playing the instrument, but they ultimately just listened by this person's really good. You can't necessarily do that with employment per se, but there can be some blind resume rounds.

I'm not saying you get into the witness protection program, and you alter the voice. That might be a little bit extreme, so I can see what they're doing to increase the poll.

And I do believe in diversity. I do believe in affirmative. I don't believe in quotas but in affirmative action. Absolutely. I do agree with in terms of reaching a goal of having diversity, but there's lots of ways to do it, but I think, too, you don't want to root out bad talent. You want to open the door and basically remove the barriers that have been there.

I think if we remove the barriers and start rethinking how we discriminate on stereotypes, it's not even anything we're not paying people differently, but it's the expectations that we have. There's a lot of education that has to be done.

So in the meantime, like a band-aid, whatever it may be done to increase the pool. Yes. Then everything goes, but let's be as fair as we can to everybody because the purpose of writing the book is not to say, "I want to make it bad for men."

That's not the goal, but it's so bad for women in terms of the parodying the expectations, we can't go with what we see right now. We're just going to get the same outcome that we've had for the last century.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'll go on the pedestal for a second here, my experience, and I've been in Silicon Valley for decades, Apple, Google, various startups, now Canva. My observation is that the hardest thing in these organizations is the war for talent, which is to get great people.

And that's the gating item and why you would reduce the pool that you draw from because of discrimination of any kind is just so ludicrously stupid to me. It's a war, and you want the best talent.

Why would you preclude a large population? And I have never understood that. It is so stupid, but I digress.

Gloria Romero:

But remember as well, it's not just the pull to get in, but then the challenge really becomes, how do we stay there? And so that's where oftentimes you start dealing with the friction, and the rub is once you get through the door and get in the door, whatever the pull maybe, then it's, "Oh, she's a witch. And I don't like her, she's mean, or she's bossy. She's abrasive. She yelled at me. She's demanding, my God, she's demanding."

So that's where it's getting through the door and then moving up the ranks and staying there because that's where a lot of women in leadership, or for example, in the political world, face the stereotyping and then the denigration, "Let's take them out," because we can't bear to have a woman who "cackles."

Guy Kawasaki:

The bottom line is that men are just going to have to learn how to deal with strong women because that trend is irreversible.

I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People.

Maybe I should rename it Remarkable Women, because I have so many remarkable women on this podcast.

My thanks to Peg Fitzpatrick, Jeff Sieh, Shannon Hernandez, Luis Magana, Alexis Nishimura, and last but not least, the drop in queen of Santa Cruz, Madisun Nuismer.

All remarkable people, all who can freely cackle whenever they want.

Until next time, Mahalo and aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Leave a Reply