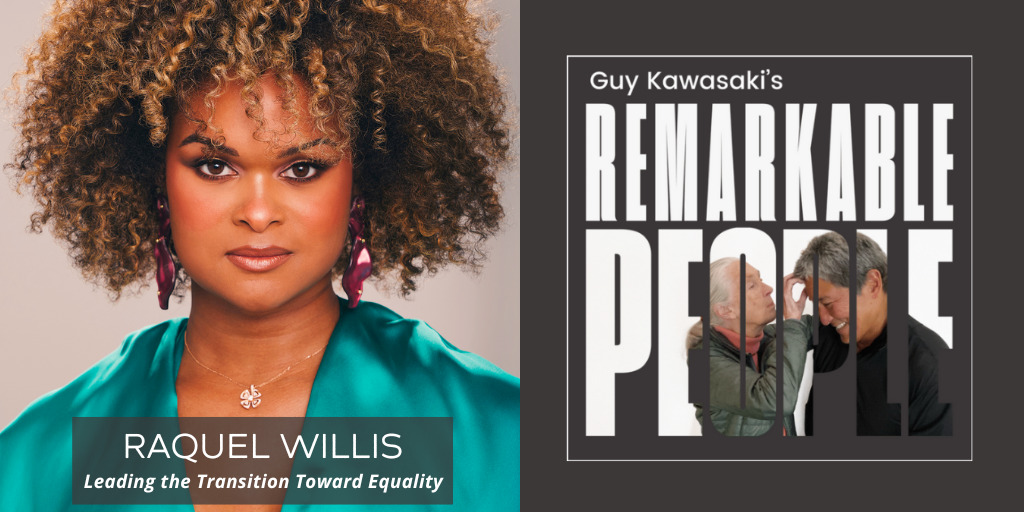

Welcome to Remarkable People. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Raquel Willis.

Raquel is a multifaceted force for change—a trailblazing Black transgender activist, a gifted writer, a media strategist, and a passionate speaker. Her dedication to uplifting marginalized voices is at the core of her work, and she has made a profound impact on the LGBTQ and racial justice movements.

During this episode, we delve into Raquel’s journey, from her groundbreaking roles as the communications director for the Ms. Foundation to her time as the executive editor of Out magazine. We also explore her co-founding of Black Trans Circles, a project that is actively developing Black trans women leaders in the South and Midwest.

Raquel’s visionary work has garnered her numerous accolades, including ESSENCE’s Woke 100 Women, Forbes 30 Under 30, and a place on Fast Company’s inaugural Queer 50 list. She’s also recently released a thought-provoking book titled “The Risk It Takes to Bloom: On Life and Liberation.”

This episode is a deep dive into Raquel’s activism, her dedication to social justice, and her mission to empower and uplift voices that have been historically marginalized. It’s a remarkable journey that promises to inspire.

Thank you for being part of the Remarkable People community, and together, let’s continue to champion change.

Please enjoy this remarkable episode, Raquel Willis: Leading the Transition Toward Equality

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Raquel Willis: Leading the Transition Toward Equality

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. We're on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is the remarkable, Raquel Willis. She's a trailblazing black transgender activist, writer, media strategist, and speaker. She's dedicated to uplifting marginalized voices. As a leader in the LGBTQ+ and racial justice movements, she's held groundbreaking roles such as the Communications Director for the Ms. Foundation and Executive Editor of Out Magazine. Raquel is also co-founder of Black Trans Circles, a project focused on developing black trans women leaders in the South and Midwest.

Her visionary work has earned prestigious recognition such as ESSENCE's ‘Woke 100 Women’, twice actually, Forbes 30 Under 30, Fast Company's Inaugural Queer 50, and The Root 100, an annual list of the most influential African Americans ages twenty-five to forty-five. She's a gifted writer with bylines and major outlets such as The Root and Vice. She has released a new book called The Risk It Takes to Bloom: On Life and Liberation. I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People. And now here's the remarkable Raquel Willis. I have to say I read the section twice and I still don't understand what happened at the National Women's March when you were brought up to speak.

Raquel Willis:

So it was very convoluted. So just to give frame to the listeners, this was the first National Women's March. This was just after the election of Donald Trump in 2017. And I was asked to speak after running my mouth on Twitter back when Twitter was still Twitter about what diversity could look like in the lineup and all of these different things.

So I was invited to speak, and I was coming into this conversation as a black transgender woman. Now, mind you, visibility for the transgender community was completely different then in 2016, almost seven years ago. And I didn't quite know how I would be received by that audience. But I think as I was there and going up to speak and say my spiel about how I came to my feminism, what I thought expansive and intersectional feminism was, my microphone was cut.

At the time, I attributed that to the change in the lineup. Some of the rumors the day of by also other speakers was that they were adding some of these celebrities into the mix. And so that felt hard and disrespectful and annoying, but also I just felt like I had been asked to be there on some level for social justice cookies to say, oh, we have another trans woman in the lineup in addition to Janet Mock, a brilliant black trans author and television writer and producer.

And so I felt a bit exploited even though I made the decision to go. So I completely own that and accountable to that, but I also felt disappointed. I felt like having my microphone cut diminished my voice and what I had to say at that time. And also I think just the honor and dignity of what I had to share as a woman coming from all of these different experiences that have historically not been fully integrated into the feminist movements of our time.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wait, so you literally are saying that you were brought up as window dressing and they cut your mic?

Raquel Willis:

That's what it felt like. I don't want to say that the organizers intentionally set up those conditions. I actually don't think that was intentional, but I think the larger point was that was how I left feeling. Whereas a lot of the other women, mostly white women, mostly cisgender or non-transgender women left empowered at the start of this very harrowing era of Donald Trump in power. And I didn't, and I wanted to tease out where was that feeling coming from?

Guy Kawasaki:

My head is exploding here. Did the organizers come up and fall on their sword and said, "Oh my God, we're so sorry. Somebody kicked out a line or the microphone died or whatever." Did they ever bend over backwards and apologize for doing this?

Raquel Willis:

You're right. I leave with a bit of a cliffhanger at that intro.

Guy Kawasaki:

No kidding.

Raquel Willis:

And we circle back in the midst of the rest of the book, but the organizers never addressed it with me even to this day. But production assistance did address it in the moment because they did notice that something happened. And even the performer after I was on stage came up to me and apologized for playing in that moment and feeling conflicted about that. So it was definitely a noticeable moment of me being cut off mid-speech.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. I am amazed. Listen, I speak publicly all the time. Okay, shit happens, but not like that. That's just inexcusable. Anyway. We kind of went down this path a little bit. What's your assessment of where America is right now?

Raquel Willis:

Where is America right now? I think that I've been joking a bit lately that people often say that transgender people or queer people are the ones who are confused or having an identity crisis. But honestly, I feel like some of the most rooted and grounded folks I know are trans and queer. And I think actually overall our society is in a bit of an identity crisis. When I think about politically where we are, I think we're in a time where it's weird. We have more information at our fingertips than ever before.

Ostensibly, we have more opportunity for communication and connection than ever before with all of these different tools. We got our phones, we got social media, we got our laptops, we got all of this stuff, and yet I think we're also not hearing each other as well as we could. I think that we're not embracing nuance enough and there's a digital distance that is taking a toll on all of us.

We're forgetting that people are human beings and that we're not just the brands that we have made ourselves to be on social media. A phenomenal writer, Naomi Klein has a book out right now called Doppelganger, which really delves into that. I can't read to delve into it myself, but I listened to an interview she was having about it.

So that's happening. And then I think politically as well, more specifically for transgender people, we are in a time culturally where we've never been this visible in the United States, and yet we're also the most under attack because of how visible we are with all of these hundreds of bills across the country that the conservatives are really trying to push to lock us out of the ability to live our lives on our own terms. And at the heart of that though is that it's not just trans people who are under attack.

I think and what I hope people can glean from my memoir, The Risk It Takes to Bloom, which of course I insert my personal story as a black trans woman from Augusta, Georgia, from the South in there, is that we are all being held up to these expectations that we're all falling short of. So when I think about transgender people, I'm also thinking about the boys and the men who are told that they can't have certain emotions or they can't like certain colors or they can't play with certain things or have certain interests unless they want to put their masculinity, and in essence, their identity on the chopping block. And the same thing happens for women and girls across the spectrum of identity as well. So it's not just transgender people who are held down by these gender standards. It's everyone.

Guy Kawasaki:

I think like millions of people. To me, Barack Obama was like the great black hope, if you will. And now we got a black president. It's to infinity and beyond. Life is going to be good forever after. And then we went into this total shithole. I don't understand how we went from here to there. What happened? You're a young person. How do you look at that and say what happened?

Raquel Willis:

I think that we all have these moments where our bubbles burst. We're fed a narrative that progress is linear and that there's no kind of recall that can happen. And of course, after former President Obama was out of office, we saw how quickly white supremacy came to the fore in a different way because it was always there. It was even there during that kind of post-racial era that everyone was salivating over.

I think that every generation has these moments where we are forced to reckon with the fact that we have to carry the banner towards progress, and we can't rely on the older folks or our parents to do it for us because they can only take it so far. Certain generation can only take it so far. So I think that this is a very unique time as every time is unique, and yet I think it's also just cyclical and that every generation is forced to rise to the occasion.

When I think about the Barack Obama era, I was having a totally different experience. Yes, I think as a young black person and going into college, I think I was a senior in high school when Barack Obama was elected for his first term. And I thought that the world was laid out ahead of me as a young black person. But of course as a gay person at that time, because I didn't have the language to understand my transness yet there was no marriage equality. The world was not laid out before me. I was still dealing with all of these other boxes and restrictions.

I don't know what it felt like for someone who maybe felt completely free, and I don't know who does actually feel completely free. I don't even think the people that we assume feel completely free do. I don't think white people in general feel free. I don't think that men feel free. I don't think that even rich people necessarily feel free. I think they try to make themselves feel that way. And oftentimes that's on the backs of other people. As Toni Morrison might say, "Who are you when you have to rely on other people being on their knees to feel powerful?" I think that is so resonant to today.

Guy Kawasaki:

What do you think Grandma Ines or how do you pronounce her name?

Raquel Willis:

In the South we would say Ines, but if she was flirting with some guy at the grocery store, she might say, "It's Ines."

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. So what do you think Grandma Ines would be saying right now?

Raquel Willis:

That is a good question. I like to give my grandma and also my father, who I both talk about their passing within six months of each other. I like to give them grace that they would've been able to evolve just like I did and just like the rest of our family did in terms of understanding me. So my grandma was a very prim woman. Now, she was not wealthy or anything like that, but she definitely gave you that kind of southern debutante feel. If you think about the Dominique Deveraux of Dynasty lore who Diahann Carroll so beautifully portrayed back in the 1980s before my time, but of course I know that iconic character.

She gave that air of she knew she deserved to be here, that she was the epitome, the essence of femininity and womanhood, and no one was going to take that away from her. No one was going to tell her she wasn't beautiful, and she was a very beautiful woman and she heard it all the time. And so I think my grandma would be proud of the life that I made for myself as a transgender woman. I like to think that.

Guy Kawasaki:

You can say you don't want to answer this question. You mentioned your father, your mother, your grandma. What's the relationship with Chet now?

Raquel Willis:

Chet, my brother.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah, your brother. He was the least accepting, right?

Raquel Willis:

I don't want to paint him as the least accepting, but he definitely was the one who did not hold his tongue in saying what he thought and what he felt. And I think his responses were typical. So in the book I chronicle when I came out to him as gay at fifteen and how he couldn't really imagine a future for me, and he did not want to hear from me dying of AIDS in a hospital bed in a decade. That was tough to hear, of course as a teenager, and I will save the other words that he shared to me when I came out to him as transgender at twenty-one.

But our relationship is stronger now. He is still a traditionally masculine straight man who lives in the South and he holds onto his identity. So he is who he is. But I will say that I think fatherhood has softened him and made him expand in a way that I think it can change a lot of men if they allow themselves to be transformed by that.

And yeah, we were just talking last night and it was just regular conversation. It's a marvel to me at this point in my life. I'm now thirty-two, which I know you're going to be, still young. But in the trans community, we actually lost a generation of folks, of course, to the AIDS crisis in the 1980s, whether we're talking about gay people or trans people. And so it actually is in this visibility era somewhat of a newer phenomenon for us to have access to trans people across different ages because so many folks were wiped out. So it's weird to be considered older and like an auntie in the trans community because I've been living my truth for over a decade now.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm from Hawaii, and when someone calls you uncle or auntie, it is the highest form of praise. If someone called me uncle, it's not your father because your father can be a pain in the ass, but this is someone who you trust, you like, you respect. He's older. He gets that kind of respect. So when people call you auntie, that's a good thing, Raquel, that is a very good thing, especially in Hawaii. You go to Hawaii, you got it made.

Raquel Willis:

I receive it. I definitely receive it, Guy. I think it's just that I feel like it happened overnight, so I feel like I turned thirty and then people were automatically like you're an auntie in community. And now I am, actually have nieces, nephews, I call them “nibblings”. It's a gender-neutral term that I love. So I do have five nibblings, the oldest of which is thirteen. And so I am actually an auntie to my origin family. But to be that in community and sometimes to folks who are only a few years younger than me is weird. It's weird.

Guy Kawasaki:

It gets both better and worse. That's coming from a person who's sixty-nine.

Raquel Willis:

Congratulations. That's a beautiful thing.

Guy Kawasaki:

Since we're going down the roster of your family, you had this great story and I just thought it was so interesting when you went to that memorial service and your other auntie got pissed off because you had not explained to her your transition. So in hindsight, should you have told her right away or was it just bad timing? Because the memorial service wasn't exactly planned in advance.

Raquel Willis:

Right.

Guy Kawasaki:

But she got bent out of shape, right?

Raquel Willis:

Yeah. I'm of the belief in general that things happened the way they're supposed to happen. I know that's a diplomatic answer, but I couldn't imagine myself just starting my gender transition in 2012. And I'm a senior in college, so mind you, so much is happening in my life. I'm going to class to have my name respected. I'm going to get my documents changed for the first time at the DMV, and this guy is, "Oh, you're too pretty to be going through this." And so he just checked it off. There was really no agreed upon system for getting a gender marker change in Georgia at that time. At least none that I was privy to and the DMV workers weren't either.

And also I wouldn't have known how to broach that conversation with my extended family. It was hard enough just to tell my nuclear family. I don't think that there's any other way that could have played out logically. But I do understand now, and I have actually talked with this aunt since then, of course, because I let her know I shared this story in the book, I hope it's fine. How do you want me to talk about it? But we had never addressed it before I wrote it down, and I actually wrote it down at the time that it happened.

And what I guess I've learned now older, more mature, is she felt offended that I didn't feel comfortable or safe enough to tell her. Now, mind you, I don't fully know if she would've been ready to hear that truth even then either. I think hindsight is beautiful for both of us to think she would've responded in an affirming way. I don't know that that is true, because I don't know her to have known any other trans people. I didn't know any other black trans women at the time that I was starting my transition, which is so funny to think how folks often paint this idea that transness is some kind of contagion and that young people learn it from other folks.

I didn't learn my transness from another trans woman because I didn't have access to any of them in this kind of predominantly white collegiate space that I was coming out of at the University of Georgia. So yeah, all of that to say, I don't know how else it could have played out, but I'm glad that we were able to have a meeting of hearts and minds about it at this point in my life, where I'm in a different space, she's also in a different space. Mind you, my father, her brother and Grandma Ines, her mother had passed about a year and some change before this incident. So there was so much going on that I just don't know how else it would've played out, Guy.

Guy Kawasaki:

I think the important point is that she was angry because you didn't tell her about the transition. She was not angry because you made the transition. Which is a very big deal, right? That's a big difference.

Raquel Willis:

It is. When I was talking with my mom about that chapter after I read it to her initially, one thing I realized was that when I came out to my mom and my dad as gay as a teenager, before I knew anything about my transness, they swore me to secrecy. They didn't want me to talk to anybody about, and this is the mid-2000s, so it's a different time. This is pre-Glee, Ryan Murphy television show that had this iconic gay character in it. And all of these moments that we're talking about, including this incident with my aunt was pre-Laverne Cox being on Orange Is the New Black by several months.

There was no visibility for transness. I fully expected people to just completely write me off, but because my parents swore me into secrecy and didn't want me to talk to other folks about my queerness when I was a teenager, I also wrote off my extended family. And so it felt like I'm just going to tell people that it's completely necessary to tell, and then everything else will fall into place. Now, was that the right approach? No, but that was the conditioning I had from my teen years.

Guy Kawasaki:

When you think about, you mentioned all the laws that are being passed and stuff, my perspective on this is that it is so hard to run your own life. Why are all these people trying to run other people's lives? Why don't they just leave everybody alone? I just don't get it.

Raquel Willis:

Yeah, I don't get it either. A lot of it is about power, of course, and unfortunately, our society, particularly in the United States, there is a long history of folks, particularly white people, particularly straight people, particularly cisgender people, those who have access to this idea of being normal under the American umbrella of them wielding power over others so that they can feel better about themselves.

And I think that's a lot of it. I think there is a fear that if too many people, if even young people know that there's such a range of experiences, that will impede on their ability to live their lives. I think that's at the heart of conservatism, is that there's a fear of anything other than the status quo. Because on some level, they're admitting that the status quo works for them and not for others.

Guy Kawasaki:

And then there's a book called Irreversible Damage: The Transgender Craze Seducing Our Daughters. How can such a book be written? I don't even understand that.

Raquel Willis:

I think a lot of it is a complete disregard for, again, the diversity of experiences. There are plenty of cisgender women who feel like the existence of trans people and particularly trans women is a threat to them. Never mind that those tend to also be the women who don't give any energy to the passing of abortion laws, which are actually impacting their ability to make decisions about their lives and their bodies. So trans people have been a convenient scapegoat for a lot of people who don't want to actually address that society as it is, has not been working for them.

Guy Kawasaki:

But this is a naive and stupid question on my part, but why does the existence of people like you threaten others? It's a big world.

Raquel Willis:

It's a big world, but I think that there are a lot of people because it's not just women. It's not just cisgender women who feel threatened. It's also cisgender men and straight people who feel threatened by queer people. It's whatever. White people who feel threatened by people of color. It's a feeling that the existence of this other person who's supposed to be on the bottom rung of society or lower rung of society than I am living a free life or living a life on their terms.

It means that maybe they're siphoning power away from me and away from the status that I have. And that's a very unfortunate thing, but that is also American history, even though we don't like to talk about it, even though they don't want us to learn about it in our educational system. That is the history of America, and our task is to make sure as much as possible that doesn't continue to be the future of America.

Guy Kawasaki:

No kidding. My experience is if you want power, you should give power away. That's when you get power by giving it away and empowering others, not by trying to keep it to yourself. We've had about 200 guests on our podcast, and I think that you may be the person who probably has the best understanding of what it takes to make a transition in life, because arguably, you went from boy, to queer, to woman, from child to adult, from powerless to powerful. So you made these really huge transitions. What's the Raquel Willis explanation of how to optimize transitions?

Raquel Willis:

How to optimize transitions?

Guy Kawasaki:

This is a small question. Take your time.

Raquel Willis:

The thing is that, yes, I think on the surface, my gender transition after being raised as a little black boy in the American South, US South to the woman that I am today, an activist, an author now, all of these different things, on the surface, that transition seems very drastic. But honestly, I think we all have transitions throughout our life. That is not just a transgender phenomenon. We all have transitions.

When I think about the impact of my father's death on me, the rest of my family had to transition, right? My siblings had to transition into a space of what does it mean to live a life without this parent around? My mom had to make the transition from being a wife to, and I don't even want to say a transition to being a widow, but a transition to just figuring out womanhood on her terms outside of a role, which a lot of women don't often get the opportunity to do, especially cisgender women.

For me, the keys to my transition have been trusting my inner voice, that conviction about who I am, even when the world doesn't understand, or even when it feels like there's this mountain of work that I'm going to have to do to get the world to understand. It's been trying to bring the people I love along for the ride, giving them space to evolve, giving them grace as well, and encouraging them to have humility about not having all of the answers.

It's been about not allowing those lows in life or those tragedies that we all inevitably face to be so thoroughly destabilizing that they keep me from seeing a capacity for change, a capacity for growth, and it's being open. It's also me being humble enough to know that I am just one within a larger collective, and that my singular life story is just a thread within this larger rich tapestry of a bunch of other stories. And what fuels me is figuring out the connections between those different threads and trying to focus more on those than simply the differences.

Guy Kawasaki:

Including myself, I must say, I'm relatively ignorant. What happens to you emotionally, physically as you go through hormone replacement therapy, and then bottom surgery. If you don't want to relive all this, it's okay, but I bet a lot of people are wondering, what's it take?

Raquel Willis:

What's it take? I will let people read the book to hear the inner details of my bodily changes and everything there. But I think when we're talking about gender transition, there's so much emphasis on the body piece, but I actually think that the bigger pieces for me were definitely more psychological. It was about figuring out what desires I had for myself, for my journey on womanhood were mine, what things I may have internalized from society about what a woman was supposed to be.

What are the things that I actually was invested in subverting or saying, actually, that's bullshit, or actually, that's not the women that I know. When I was starting my medical transition at the University of Georgia, I was largely surrounded by women who didn't look like me or have similar bodies to me. And that was just thinking racially, right? I was often surrounded by white cisgender girls, petite women, people who maybe fit more of an ideal within our society of womanhood.

But when I thought deeper about the women that I come from, black women, full figured women, fat women, women with all types of different bodies, that was comforting. Women who had different voices, who sounded different. I even talk a little bit in the book about what it was like to go to vocal therapy because I did have a much deeper voice before my transition.

And when I went, the vocal therapist was telling me all of these things about, "Your voice has to sound like this, and you need to use more adjectives because that's how women talk." And all of these stereotypical ideals. But hey, those are the things that we associate even still with womanhood. I'm so grateful that we live in a time now a little bit more where those aren't the standards for every woman. There are women who have shattered what womanhood can be and look like.

I think what also feels important to say, especially in a time when folks are trying to push legislation to lock trans folks out of accessing what we call gender-affirming care, is that people have so much ire. Some people have so much ire for trans women, for instance, who may modify our bodies or trans men who may opt for hormone replacement therapy or all of these things, but there are cisgender people who opt for those things too. And we don't give them the same kind of ire. When I think about gender-affirming care, it's not just the trans thing. It's a cis thing. Cis people do all kinds of things to fill at home in their body, to fill at home in their gender, and trans folks deserve that same access and right as well.

Can I say one more thing? What I will say about bottom surgery, and I try to talk as eloquently as I can in the book about this, is when I had bottom surgery several years ago, I was contending with this idea that to really be a woman, to really be respected, I would have to go "all the way." And there's this idea that we're forced as trans women to contend with. That to really be a woman, you have to have a certain type of transition.

And I wanted to speak to in the book the chapter that delves into that experience that I actually reject that idea. That yes, even though I opted for bottom surgery in my own journey with my womanhood, that is not a standard that other trans women and trans folks should be held to. And so I actually don't think that it is a fruitful idea for us to require trans people to prove our gender by having a certain type of medical transition.

Guy Kawasaki:

And then you went to that nightclub in Oakland, and you had a very ugly experience, right then. This is after the bottom surgery, right?

Raquel Willis:

This was, yes. Yes. So I was living in Oakland. I was working at Transgender Law Center at this time, which shout out to them for covering gender-affirming care. That was the first job, probably the only job I ever had up until that point that had insurance that covered bottom surgery or vaginoplasty as we would say technically.

Just a few months after recovering, I went out with some girls. And so in that chapter called “Girls Night Outing”, I talk about what it was like to be a young twenty something trans woman who just wanted access to what a lot of young women want, just to go out, have fun, maybe talk to a cutie. Maybe take a swig of a nice drink and dance on the floor, and how that felt so inaccessible to me. And the women that I was out with were trans women who flew under the radar. So were not read necessarily as trans.

And so what does that mean to be dancing with a guy who came up to me and have this internal battle about, okay, should I tell them or should I just cut my losses and not talk to him? Because I don't want to have to go through what may be a difficult experience of telling him that I'm transgender. And then of course, also dealing with sexual harassment, which I detail at the end of that night that happens. And what that means in a culture where people say women deserve whatever comes our way, but also that trans women, oh, and also black trans women deserve whatever harassment or violence comes our way by daring to try and live a life full of joy like any other person.

Guy Kawasaki:

I don't understand the logic at all of black trans woman is a person you should beat up on.

Raquel Willis:

Yeah, we can talk so much more about it. There needs to be seminars on why black trans women experience what I call Afro trans misogyny in the book, this particular ire that black trans women face where we are women who are living in the margins of the margins. So we are black. And so we are living in a society that overwhelmingly is in cahoots with white supremacy. Historically and currently, we are living in a society that is overwhelmingly in cahoots with the patriarchy. And so misogyny is still rampant, right? And we are also transgender and/or queer. And so we're living in a society where the default is still straight and cisgender. Someone who identifies with the gender that they were assigned at birth.

And so I end that chapter, “Girls Night Outing”, discussing how we are painted as a villain, as a victim at the same time as a predator, as a threat in so many ways. I think when we're talking about interpersonal violence or maybe intimate partner violence, a lot of black trans women are dealing with, particularly if we date men and cisgender men specifically, we are dealing with being seen as a threat to their manhood and masculinity. And in essence, a threat to their status, a threat to their position in our society, a threat to their power. And that often puts us in the position of being on the receiving end of their insecurities and their fears about what their interest or attraction to us means about who they are.

Guy Kawasaki:

In September of 2023, do you feel safe?

Raquel Willis:

Do I feel safe? Oh, that is a big question. I don't know that I will ever feel completely safe. As a black person, I am constantly dealing with so many conflicting emotions of just gratitude that I have had the opportunity to build a life for myself, but also of constantly being in a state of rage as James Baldwin so eloquently said. "To be Negro is to constantly be in a state of rage." I may be butchering that quote. Or obviously as a woman, I cannot just walk around New York at night in the same way that some of my best friends who are men can and particularly cis straight men.

And then of course, to be a trans woman, there will always be a little part of me that maybe has some anxiety about being recognized in my transness out and about, and also to be visible. So there are people who know me and know of my work in media, and so what kind of risk does that put me at? But I will say that I have no regrets of being outspoken, being a loud mouth, being a visible trans woman because I've created this life on my own terms, and it is what it is. Old African-American proverb. It is what it is.

Guy Kawasaki:

I think Grandma Ines is smiling right now.

Raquel Willis:

I hope so.

Guy Kawasaki:

Believe it or not, this next question is really personal and practical for me. Okay? I have people who are in the process of transition who are my friends, and I met them when they were more on the male spectrum than the female spectrum. So sometimes in conversations I don't catch myself and I use the masculine pronoun. And trust me when I tell you it's not because I have anything against this transition or their gender, anything, I just slip up. So now is this something like I'm committing a really heinous kind of insult hurtful thing, or is it just a slip up?

Raquel Willis:

You know what's so funny, I literally was just talking about this with my mom on a phone call right before I started talking to you, because she was talking about how I have some extended relatives who in her presence sometimes misgender me, sometimes use the wrong pronoun. And they're older relatives, and I don't say that as an excuse, but just to give more context. It's so beautiful to hear her talk about that harm as something that also harms her.

It is so aggravating to her that it's almost as if I'm there in person experiencing it. And she, as my ultimate ally in this journey, corrects them. And she talks about the work of correcting them because it is work. It's not the same work that the person who most experiencing the harm has to do to endure or make it through or correct, but it is a harm and it is a work that the ally feels.

And so that's the thing. Allyship is not easy, honey. I think that people have this idea that once you wave a flag once, you're good. You go to that one Pride Parade, honey, you're ally of all time. But allyship is not this badge or this button. It's not a Google certification. It is active. It is something that is ever evolving. It is something that shifts depending on context, and it requires us to be nimble, but it also requires us to be loyal and have an allegiance to those people we say that we honor and respect.

So I can understand and even empathize with the fact that for someone to experience the transition of someone close to them, it requires work. And I say that as a trans person who has had many friends who have changed names and changed identities. In our community, you got to ask sometimes, "Hey, where are we? Did anything shift if I haven't talked to you in a while?"

But what I will say is that we have to be willing to admit that harm is harm. Harm is not just the big things. Harm isn't just something that Donald Trump does. It's not just something that the Westboro Baptist Church does. Harm is not just a burning cross in the front line, right? Yeah. Misgendering somebody is disrespecting them. That is harm. And that doesn't mean the moment of harm is the same, but it is still what it is. And we have to be willing to be accountable to it. We have to be willing to be wrong. We have to be able to sit in the discomfort that we are capable of harm, every single person.

And so if you get it wrong, apologize, but in that apology, maybe spare the excuses and just make a commitment to do better next time. And when I say make the commitment, that means you actually have to deliver on it. So that does not mean you get a million more passes to make that mistake and then say that it's innocent, because at that point, it's starting to become intentional. It's starting to become willful, and if not, you're being harmful in a cavalier manner, and that's unacceptable as well. That's what I would say.

Guy Kawasaki:

I am so glad I asked that question.

Raquel Willis:

Yeah, I think that we, all of us, have a hard time accepting that we could potentially be harmful, and now this is dramatic language, but we could potentially be the villain in the moment. But it's true. So get accustomed to the real full-throated apologies and keep it moving.

Guy Kawasaki:

I hope old dogs can learn new tricks.

Raquel Willis:

I think they can. When I think about our ability to evolve, going back to my mom and my dad, my parents were born in the 1950s. And when they were born, their birth certificates said Negro. Now in the course of their lifetimes, we collectively went from saying Negro on official documents to saying African-American, to saying black, not to mention colored was up in there somewhere too. If we can make those evolutions collectively, I think we can figure out how to respect people in terms of their gender. And I'm not saying that race and ethnicity and gender are the exact same things, but there are some lessons we can glean from those kind of societal evolutions.

Guy Kawasaki:

Thank you. So in many places in your book you mentioned online communities and information and what positive factors there were. And yet, social media and online has such hate, misogynist, racist, you-name-it-“ist”. So what's your take on social media and the use of social media for someone who's going through things like this and transitioning?

Raquel Willis:

You're absolutely right. The internet is so different from when I was first coming into my queerness. So my internet journey, because we all have a start, was in the early 2000s, Yahoo Chat Rooms, AOL Instant Messenger. Pre-Myspace. I was privileged enough to have access to a computer because my mom taught business and office technology locally.

And so we always had a computer in the house. And then by the time I was about twelve or thirteen, I had my own hand me down computer because she got a new one. I was on that thing all the time because that was the only access I had to other LGBTQ+ folks because I didn't know anyone who was living openly queer at the time, much less who was also around my age. And that was an outlet. Fast-forward to now, social media is a different beast altogether as a part of the internet.

I think what we have to remember is that the internet is a tool, right? It's only as benevolent or malevolent as the folks who utilize it. And unfortunately, we live in a time where people have learned how to weaponize this tool to win elections, to move popular opinion in maybe the wrong direction, depending on what we're discussing or the communities we're discussing. And we need to be holding those agents of discord accountable, and we need to be taking control of our media diet.

Where are we getting our news? Are we just getting it from the Instagram pages that lift the worst narratives about people and communities? Or are we actually taking an active part in what we consume in terms of media? Because it is like food, right? It's, are you just eating the disgusting nothing burger, or are you getting grass fed, honey? And I also, as someone who works in media, I'm an executive producer over at iHeartMedia on their Outspoken Podcast Network.

And so we are bringing to the fore two podcasts that I'm hosting. One is called “After Lives”, which focuses on the story of an Afro-Latino trans woman who died in Rikers custody in 2019. Her name was Layleen Polanco, and another show called “Queer Chronicles”, which delves into the stories of youth in red states.

So I'm hoping I can contribute authentic narratives to offset the disgusting ones that are out there often about queer and trans communities, but we also have to hold the larger outlets accountable. The New York Times has gotten its fair share and probably deserves more criticism for how it has dropped the ball in covering authentic trans narratives over the last few years when we've seen this heightened political violence. And journalists, particularly trans journalists, are holding them accountable along with GLAD, I think people just have to be vigilant in what they consume.

Guy Kawasaki:

What does RuPaul signify to you?

Raquel Willis:

What does RuPaul signify to me? That's interesting. I think to be candid, there's a lot of nuance I have to insert into discussing RuPaul now because we live in a time where there has to be a discussion on the distinction between drag performance and transgender identity. I say that also acknowledging that there are transgender drag performers who do a beautiful job. But RuPaul was really the first openly queer figure that I, and probably many others consumed in the 1990s. So I remember being fascinated whenever she would show up in a television show or show up in a commercial or something like that.

And so when I encountered drag in my real life in high school, it was when my sister took me to a drag show at a famous dinner theater spot called Lucky Cheng's in New York City. And that was the first time that I really saw drag up close and up front, and I saw people who were unabashedly playing with gender, and I was in this amateur contest that my sister raised her hand and pushed me to be in, and I was so nervous.

Guy Kawasaki:

And you won.

Raquel Willis:

And I won that little amateur contest just weeks before I was headed off to college. And it's so interesting that drag would circle back around as a pivotal art form in me understanding my transgender identity months later. So shout out to RuPaul for creating a pathway for so many folks to understand their queerness and gender nonconformity, and shout out to my sister for forcing me to be in that amateur drag contest, which would later prove so pivotal.

Guy Kawasaki:

I bet that Jessica and Chet had a few very interesting conversations behind your back, right?

Raquel Willis:

Maybe I need to ask them because I have not been privy to what those discussions might've been. Now I know my mom was always having conversations with my brother and hearing his concerns, but also hearing his evolution.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah. Great. Okay. Second question. And it's actually the person who is going through this transition. When I told her that I was interviewing you, she told me specifically ask you this question. Okay?

Raquel Willis:

Okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

You ready?

Raquel Willis:

I guess so. We'll see.

Guy Kawasaki:

What are your top three Beyonce songs?

Raquel Willis:

Oh, gee. Oh, gosh. Of all time? That's hard. Okay. Top three Beyonce songs. It's hard because Renaissance, the whole album has some bops, but I have to say I love “Heated”. I have to say Heated. I have to say, oh, am I? Oh, gosh. We're going to say Heated. I'm going to try to choose from different albums. No, I'm lying. I'm not going to say Heated, even though I want to, and it's my favorite song off the album. I'm going to say “Cozy”. I have to say “Cozy” from Renaissance, her latest album, because it has Ts Madison on it. It really truly is a black trans anthem. I would say “***Flawless” was so important for me as a young black trans woman coming into her feminism from her self-titled album, which is complicated because she uses a quote of a feminist who has an anti-trans record now, so that's wild.

I won't say her name. People can Google. And then the third song, I think we're going to have to go back to the first album, and this is a song that people do not give enough love, but I'm going to say “Hip Hop Star” because it also has Big Boi from the Outkast on it, and that's a deep Atlanta, Georgia Southern record. And my chosen sister, Toni-Michelle Williams, who I also talk about our relationship in the book, she made me realize the glory of that song recently. Yeah, I chose from three different eras because I'm a loyal bee in the beehive.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. All right. My last thing. This is both a question and your opportunity. The question is, what's your advice to young people? And weave that into your pitch for why everyone should read your book.

Raquel Willis:

Oh, wow. My advice for young black people, young trans people, young queer people, young women, is to trust your convictions, find community, and find a pathway to express yourself. That can be art, that can be athleticism, it could be so many different things, but those things are core to my experience. So yeah, convictions, community, and creativity. And so I'm giving you three Cs. Look at me.

And then the pitch for my book, The Risk It Takes to Bloom. If you are interested in an account of an unapologetically southern black trans woman and her journey to her identity and also her journey, owning that identity within a career in journalism and a journey in activism with the backdrop of the Movement for Black Lives and contemporary feminist movements and the contemporary LGBTQ+ movements, straddling the eras of Obama and Trump, and somewhat Biden, then check out The Risk It Takes to Bloom. And I hope that it will inspire you to take your own risk to bloom in your own life and to also shatter all of those expectations.

Guy Kawasaki:

I hope you enjoyed this episode featuring Raquel Willis. What a story of courage and passion and changing the world. Be sure to check out her book, The Risk It Takes to Bloom, because blooming does involve risk. My thanks to MERGE4 for sponsoring this episode, the creator of the world's coolest socks, use that promo code “friendofGuy” to get a 30 percent discount. Now, I want to thank the people who helped me bloom, Jeff Sieh and Shannon Hernandez on sound, Luis Magaña, Alexis Nishimura, and Fallon Yates, plus the Nuismer sisters, Tessa, and the Drop-in Queen of Santa Cruz, Madisun. Thank you for listening. I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People. Mahalo and Aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply