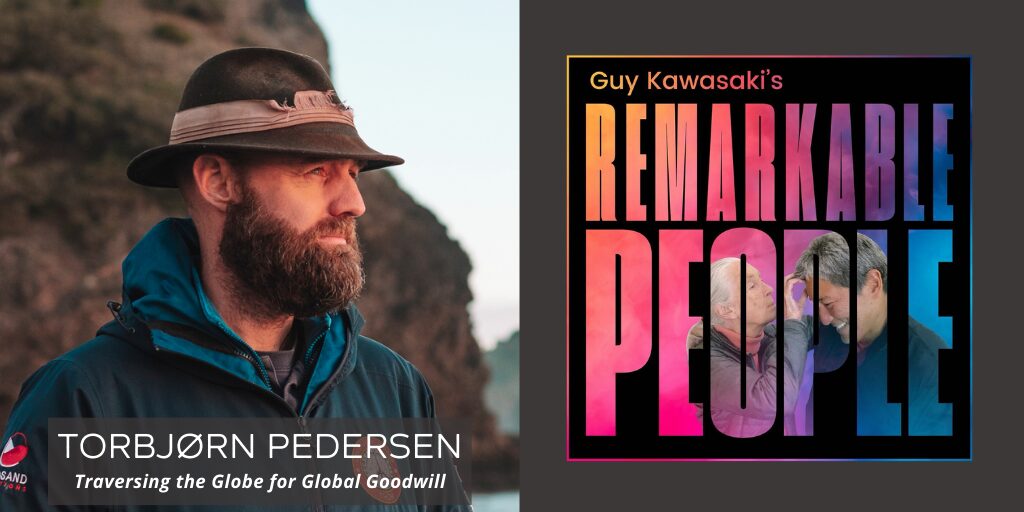

Welcome to Remarkable People. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is Torbjørn C. Pedersen, known as “Thor,” a remarkable world traveler who just completed an unprecedented decade-long journey to every country strictly by land and sea transportation.

Thor was driven to promote global unity by attempting something no one had done before: traverse the entire world relying only trains, boats, bikes and his own two feet – never flying. Logged in his blog “Once Upon a Saga,” his voyage brought new understanding of how interconnected our world is, despite barriers or politics, through basic human bonds.

Thor spread goodwill by highlighting everyday heroes and visiting Red Cross societies in 195 countries, discovering their overlooked, lifesaving efforts. Thor cemented bonds worldwide, culminating in shattering records to complete this epic Odyssey.

His legacy proves how total strangers share common hopes and how a stranger is simply a friend you haven’t met yet.

In this episode, learn what shaped Thor’s remarkable ambition, how he endured this decade-long quest, and the biggest lessons he brought back to inspire unity across borders.

Please enjoy this remarkable episode, Torbjørn Pedersen: Traversing the Globe for Global Goodwill.

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Torbjørn Pedersen: Traversing the Globe for Global Goodwill.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People. We're on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me today is Thor Pedersen. I hope it's Pedersen, not Pedersen. I should have asked him in the interview but I completely forgot.

I cannot definitively find the answer, because all the YouTube videos in which he's talking, he never says his last name. Alas, that is probably not the biggest problem we face in the world.

Let me tell you about Thor.

He is a Danish adventurer. He made history by visiting every country in the world without flying. His decade-long journey is a testament to human connection, and, oh my God, the spirit of exploration.

His blog Once Upon A Saga chronicles his adventures across all these countries, oceans, war zones. He even got married atop Mount Kenya in 2013. Throughout his travels, Thor engaged with local communities, shared stories, and really fostered cultural unity.

He also shone a light on the critical, yet often unseen, work of the Red Cross Societies. Thor's odyssey demonstrates our world's deep interconnectedness, and it echoes his belief that a stranger is a friend you've never met before.

Join me, Guy Kawasaki, the Remarkable People Podcast, as we delve into the incredible, remarkable journey of Thor Pedersen or Pedersen, who visited every country in the world without flying.

My wife is Danish, so I've had many an ebelskiver in my life.

Thor Pedersen:

What does that mean?

Guy Kawasaki:

You don't know what an ebelskiver is? Maybe I'm saying it wrong.

Thor Pedersen:

No. I'm sure you're saying it exactly as it's supposed to be said, but I am just not from the US, and I speak Danish on a day to day basis.

Guy Kawasaki:

Hey, I'm having an out-of-body experience. Ebelskiver is that thing that's like little donut pancakes. That's a Danish thing.

Thor Pedersen:

Okay. Now I know what you're saying. Yes. Okay. No. Your pronunciation is very good. It might be a different dialect. Where I come from, I say ebelskiver.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's Hawaiian pigeon saying ebelskiver.

Thor Pedersen:

Yeah. I wasn't ready for you speaking Danish just yet. I'm very impressed.

Guy Kawasaki:

First, I want to start way back when, and I read that you were the lifeguard at the Royal Palaces? What the hell kind of job is that? Tell me about that.

Thor Pedersen:

Denmark is a cute little country with a very small population, and very old traditions, in some directions, at least. Within our military service, you can get drafted or not. That's through a lottery. You put your hand in to a box and you pick a number, and if the number is low, then you have to do your military service and if the number is high, you can go out and get a job if that's what you want.

My number was really low, and then I signed up for what I thought would be the most interesting branch within the Danish military, which is to stand as a guard in front of the Queen's Palace. That's in an olden day outfit. I think that uniform has not been updated, certainly, for a very long time. It's with the bearskin hat on top of your head. It wouldn't be good for warfare. They would spot you a mile away. It looks nice, though.

Guy Kawasaki:

You get drafted by the Danish army, and they say, "You can either go fight the Russians or you can stand in front of the palace." You get that kind of choice?

Thor Pedersen:

Within our military service, you can go Air Force, you can go Army, you can go Navy, and then if you feel like it, you can do something a little bit more special, so that's actually a twelve month military service duration, which is longer than any of the others.

Guy Kawasaki:

Herein lies the problem. When I read that in your bio, I read lifeguard. When Madisun and I or people, basically, in California, Hawaii, when we read lifeguard, we think swimming pool or ocean. You meant palace guard. Right?

Thor Pedersen:

Yes. It's a palace guard.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, I thought you were watching the Danish princesses swim for your military duty.

Thor Pedersen:

You are picturing Danish Baywatch.

Guy Kawasaki:

You're the Danish Hasselhoff?

Thor Pedersen:

Yes. I'm not as buff as him, though.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. First serious question is you've been all over the world, obviously, and I want you to explain, because I don't think many people understand, it's not clear I understand, what exactly does the Red Cross do around the world?

Thor Pedersen:

I'm very happy that you asked me that question, because I've done a great deal of interviews, and, most, they skip directly over that. I was given the honor of traveling as a Goodwill Ambassador of the Danish Red Cross, which is the National Society of Denmark, and the National Society of the US would be the American Red Cross and the National Society in Syria would be the Syrian Red Crescent, and so on and so forth.

The Red Cross is the world's largest humanitarian organization and found in 192 countries around the world, so that's, basically, every country. My job was to promote the humanitarian efforts and raise money and awareness. I donated blood, I shared as much as I possibly could about the Red Cross throughout the entire journey, and if you have any specific questions about the Red Cross, then I'm more than happy to answer them.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let's say there's a tsunami or something. What does the Red Cross do?

Thor Pedersen:

It would very much depend on the country. The Red Cross plays an auxiliary role to the government, so in some countries, the government might be very strong and there would be less of a need for the Red Cross.

In some countries, the Red Cross would take over the entire operation. The backbone of the Red Cross would be volunteers and within a tsunami for sure, lots and lots of volunteers would be sent in.

They would immediately start to help those that are affected by the tsunami and maybe people they cannot return to their homes, maybe they need a hotel, maybe they need a shelter, they would set up shelters, they would hand out food and blankets, clothing, sanitary pads, toothbrushes, soap, anything that you can imagine to get people back on their feet.

In some cases, the Red Cross might contact your employer on your behalf and explain to your employer that your life has been destroyed, because you might be dealing with trauma or something else, and they might have arrangements with hotels and they would set you up, and they would contact the insurance and help you.

The Red Cross is there in place to help people and the level of the Red Cross engagement really depends on the country.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let's suppose that you're with the Danish Red Cross and you're sitting in, I don't know, Copenhagen and you're drinking beer, and then there's a tsunami in Indonesia. What? Does your phone ring and they say, "Thor, get on a plane. We've got to go to Indonesia"? How does it work?

Thor Pedersen:

That could happen actually, because I was trained to be within the ERU. I was a logistics delegate within the ERU. The ERU is the Emergency Response Unit. That's a team of specialists that are trained to be deployed on short notice. That could very well happen.

Then I would get deployed along with some doctors, some engineers, some technicians, some nurses probably, and then we would set up camp near the area in Indonesia, and then we would go to work immediately, rebuilding the country, and supporting the National Society of Indonesia. In that case, the Danish Red Cross would be a PNS, which is a Participating National Society.

The more likely scenario, I would imagine is that the Danish Red Cross would immediately start raising funds within Denmark, and then all these funds would be directed to Indonesia.

Guy Kawasaki:

Who decides whether it's the American Red Cross or the Danish Red Cross or the Finnish Red Cross? Who gets involved? Does the people in Thailand say, "Let's call our buddies in Denmark or let's call our buddies in New York"? Who gets to call?

Thor Pedersen:

That's another good question. The way it works is that if a national society is not strong enough to handle the emergency on its own, then it would put out an appeal and then Participating National Societies, PNS, they will answer that appeal, so it might be whoever is already within the country, it might be that in Indonesia, the American Red Cross is already there operating, and then it's easy for them to deploy or redirect some of their efforts to the tsunami.

It could also be that you would have a country traveling across half the planet to go and help and assist. Within the Red Cross, you have the IFRC, the International Federation of the Red Cross, which is headquartered in Geneva, in Switzerland, and they help coordinate in these cases. When this appeal is raised, then the IFRC would probably reach out and find appropriate national societies to go in and help and support. The IFRC also has its own funds.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. You have about quintupled my knowledge of how the Red Cross works in the last sixty seconds.

Thor Pedersen:

I can tell you a fun fact. If I wanted to pursue a Guinness World Record within the Red Cross, then I could probably be awarded the one person on this planet who has visited the Red Cross in the most amount of countries. I did visit the Red Cross in 198 countries around the world throughout this journey.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. That's a good segue. Explain what you did.

Thor Pedersen:

Yes. Back in 2013, I found out that no one in history had gone to every country in the world completely without flying. That basically infected me. I just couldn't shake the idea. It grew and it grew within me, and I spoke to friends, and I spoke to family, and no one I spoke to had the same interest within the topic as I did. I was smitten, and I eventually started planning. There was a wonderful woman within my life.

I'm happy to say that today she is my wife but back then she was my girlfriend, and we had a talk about how long we thought this would take, and I planned it out. I did the logistics. I raised the funds for it, partnered up with companies, and set out on the Tenth of October 2013 at 10:10 A.M., thinking it would take four years to visit every country in the world completely without flying. It got very complicated very fast, and sometimes it was easy, sometimes it was hard.

It was by far the biggest ordeal I have ever had within my lifetime. It ended up taking nine years, nine months, and sixteen days, in part because of the global pandemic, in part because of conflict and strife broke out in certain countries and regions, in part because I was sick, in part because of the Ebola epidemic, which I think most people might have forgotten, it was somewhat behind the global pandemic. Yeah. I was delayed in many places around the world.

Guy Kawasaki:

When you were stuck in Hong Kong for two years, what did you do in Hong Kong for two years?

Thor Pedersen:

Yeah. I didn't know it was going to be two years. The virus broke out in Wuhan. I was onboard a container ship heading towards Hong Kong, and I was blissfully unaware about the outbreak. Then when we reached Hong Kong, I went up on the bridge and I was standing next to the captain, and I saw the captain was wearing a face mask. I look at him and I ask what's going on, and he handed me a face mask, and he said, "You better put this on. There's been a virus outbreak in Wuhan."

I say, "Okay. What's Wuhan?" He says, "That's a city in China," and I say, "Okay, how far away is that?" He said, "That's more than 1,000 kilometers away." Sorry, you might have to calculate into miles on that. It's really far away.

I figured, I think most people would, that would never have anything to do with me, that would be a local incident in a city very far away from where I was, and I entered Hong Kong where I was supposed to be for four days, just for transit between two ships, and then, eventually, those four days were extended to eleven, and then eventually, countries started closing their borders and I couldn't get onboard ships.

Then I was in Hong Kong for a duration unknown. What I did was network, and I networked, and I was shaking hands and meeting people and sending emails and calling, trying to find out who could help me on a ship and get me to the next country.

After a good eleven months of networking, Hong Kong immigration said that I had to get a job or get married to someone in Hong Kong or start studying, but I couldn't keep extending my visa. I got a job and I worked for the Danish Seamen's Church. I was an assistant servicing container ships and seafarers. They couldn't leave the ships. They were quarantined onboard the ships. I could go shopping in Hong Kong for anything they needed and bring it to the ships.

I could also help and support the Danish community in Hong Kong. There is a bit more than a handful of Danish people, about 300 Danish people living in Hong Kong, and they were missing all sorts of Danish delicacies, so I imported that and I was selling it out of the church to fund the activities.

I did a lot of hiking. Hong Kong is 75 percent nature. I took to the mountains to get some fresh air and take in the view of the beautiful territory, which is Hong Kong.

Yeah. I made a lot of good friends, a lot of collaborations, I've done many interviews while in Hong Kong. Suddenly, press started taking interest in this man who was only nine countries from becoming the first to reach every country in the world without flying, now stuck because of the pandemic.

Guy Kawasaki:

During these two years but also all nine years, where is your fiancé/girlfriend/wife?

Thor Pedersen:

Yeah. That's the right order actually. When I left, she was my girlfriend, and she came out and visited me several times. On her tenth visit, she came to Kenya, and I brought her up on top of Mount Kenya, which is the second-highest mountain within all of Africa and I got down on one knee, and I gave her a ring, and asked her a question and she said yes.

Beyond that, we were engaged and we thought we would have a nice wedding somewhere in the world, and then the global pandemic broke out. In order of having her come and visit me inside Hong Kong, it was very tightly closed, we had to be married. How do you get married when one person is in Hong Kong and the other one is in Denmark?

It just turns out that the USA came to the rescue, that in Utah, you have an agency that marries people online. We were able to have an online wedding, and that was good enough for Hong Kong and then we could arrange, and she came to Hong Kong and hotel quarantined for three weeks, and then on the other side of that, we were together for about one hundred days in Hong Kong.

Denmark didn't accept this online wedding, so at a later point when she came to visit me in Vanuatu, we got married on the beach and what happened was that a German woman living in Vanuatu was helping us. She was supposed to process this wedding with the government, with the registry.

Unfortunately, the government in Vanuatu was attacked by hackers, so there was a ransomware attack and all their data was locked and they couldn't move anything, and it's very close to a year now, and we're still not officially married in Vanuatu, so we can't process the paperwork in Denmark. But we do know that we're married in Utah, in Hong Kong, and in Vanuatu.

Guy Kawasaki:

This organization in Utah, was it the Mormon Church?

Thor Pedersen:

No. That was my first thought as well. I think that was my primary reference to Utah back in the day but now I know that they're a bit of a Las Vegas organization.

Guy Kawasaki:

I don't understand. You do this for ten years or something. Are you using the money that you raised from sponsors or are you working in these countries?

Thor Pedersen:

It turned into a big mix over time. Initially, my thinking was that I wasn't going to set out and do a thing like this unless I could have the finances covered.

I was thirty-four years old when I left home and I thought it would take four years, so I didn't want to come home as a thirty-eight year old and be in debt. Some friends and I, we thought that there had to be a company out there that would take interest in something of this magnitude.

We were able to find a company that focuses on geothermal energy. They're called Ross Energy. They decided to fund the twenty dollars per day, which was set as an average.

Guy Kawasaki:

Twenty US dollars per day? Two cappuccinos.

Thor Pedersen:

Yeah. In some countries, it's two cappuccinos. In other countries, it's accommodation, a meal, and transportation. Worked as an average. Yeah. Twenty dollars a day for almost ten years.

What happened was a couple of years into the project, oil prices were real low, and Ross Energy, they were hurting from that, so they had to pull the sponsorship. Then I started spending my own money, until I had nothing left.

Then I did some crowdfunding campaigns. I gained a little bit of finance that way. I sold some articles. I did some speaking engagements. Then when I got to Hong Kong, I was able to make some money back working at the Danish Seamen's Church.

Then eventually, Ross Engineering was strong again, and they were able to come back on again. It's been a mix of my personal funds and donations and corporate sponsorship.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. Literally, were you carrying cash or was it like an ATM card or Apple Pay? How did you literally spend the money?

Thor Pedersen:

All of the above. I would always have US dollar, because it's universal currency that you can use in any tough spot around the world. I would also always have a Euro on me. Euro and US dollars, I would have that tucked away somewhere.

Then I would have a Mastercard and a Visa card, which I could use around the world. Then somewhere between 2013 and now 2023, the world kept on developing, and more and more countries would have access where you could use Apple Pay. By the end of the project, I wasn't using cash anywhere. I was just tapping my phone.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you know what your wife's parents opinion was of this son-in-law doing this?

Thor Pedersen:

Unfortunately, not. My wife no longer has her parents. She lost them before we got married. I do know that her friends and the friends of her parents and extended family, they pretty much all thought I was crazy. I think very few people didn't think that I was crazy to do this.

Even the ones that saw a little bit of light in what I was doing, that I was chasing a difficult goal or that I was inspiring and motivating people around the world or that I was trying to look for the positive to promote every country around the world or raising funds and awareness for the Red Cross, even the people that could see some sanity within that, they saw absolutely no sanity in hanging out in Hong Kong as the sand ran through the sand glass.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now when you say most people thought you're crazy, there's two kinds of crazy. Right? There's, "Oh my God. He's crazy," and there's, "Oh my God. He's crazy. He's an idiot." Was it the negative kind or the funny humorous kind?

Thor Pedersen:

Since you're asking me, I would say that I'm the good crazy but I'm pretty sure that plenty of people out there think it's irresponsible, that I should have taken a job, I should have started a family, I should have contributed to society in other ways, and today, I have about a quarter of a million followers online that are very supportive of what I've done and are lovely.

It really depends on who you ask.

Guy Kawasaki:

We recently interviewed a woman who walked across the US, and she had similar things to say, different strokes for different folks. Right?

Thor Pedersen:

Yeah. That's a good way to put it. I'll tell you this, when I left in 2013, and when I reached 2015, so two years in, I couldn't take it anymore. I was recovering from cerebral malaria, I had lost the financial backing, the long distance relationship to my then-girlfriend wasn't going well, we were really struggling. I wasn't getting the sleep I needed.

Malnutrition. Mentally and physically, I just couldn't cope with it anymore. I had been living out of a bag, going from a bus to a train, trying to deal with the bureaucracy. I've been held at gunpoint. Several of the ships that I traveled with had sank to the bottom of the ocean by then. There was a great deal of racism towards me in Central Africa, more than likely due to hundreds of years of colonialism. I really couldn't take it anymore.

At some point, I just decided the system wasn't going to beat me and I was going to find a way and I was going to prove everyone wrong. Everyone who said that I couldn't get the next visa, or I couldn't enter the next country, I wanted to prove them wrong. I kept fighting for it, but since 2015, I've always wanted to go home.

I thought the final country was just around the corner, eventually, it would get a bit smoother, I would have the support, I would have the backing, it was just around the corner. Imagine pushing since 2015 and only setting foot back home in 2023?

Guy Kawasaki:

Didn't you fly home twice and then fly back to where you flew from?

Thor Pedersen:

No. I left home on the Tenth of October 2013. I returned home on the Twenty-Sixth of July 2023. In between, I didn't fly at any one point. I didn't return home. I spent more than twenty-four hours in every country around the world.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, some place I read, you had to fly to the UK twice or something. No?

Thor Pedersen:

I think you're confusing me with a British gentleman. His name is Graham Hughes. He's from Liverpool. He attempted to visit every country in the world without flying prior to me. I think he must have started out in 2008 or 2009. He had to fly back home several times. He also flew on holiday in Australia. He spent four years and thirty-one days completing his project.

I met the guy. He's a really nice guy. I met him in Panama. He's good crazy too.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. I read a report recently that said that of the 200 countries in the world, you can safely drink tap water in only fifty of them. Now did you find that to be true? Did you drink tap water everywhere and get sick all the time? How does water work around the world?

Thor Pedersen:

I can tell you this, I went to every country, every beautiful island nation within the Caribbean and I believe that most of them told me that they have the purest drinking water in the world.

When you talk to locals, and locals will say it's fine, because they've been living there for their entire life and their bodies and their immune system got used to the water and bacteria and this kind of stuff. You come as a foreigner, and you might have to run to the toilet for a few days but then in many cases, your stomach, your system will also get ready for it.

I really wouldn't recommend drinking tap water all around the world. If it's fifty countries around the world, I don't know. That might be true. I traveled with a water purification kit, a bottle called Life Saver, and at a later point, I had a filter, a soft flask from Salomon that had a filter within that, and I just made sure to filter all my water all around the world.

Throughout all of Africa, if you can get to a borehole and you get water straight from the underground, there's no issue. You can just drink that. If it comes from, let's say, one hundred feet below or something like that, no issues.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. Those filter things, I see them at REI. They really work?

Thor Pedersen:

Yeah. They must. Here I am, talking to you, I still have all my teeth, my liver is functioning.

Guy Kawasaki:

What's the hairiest story you have about trying to clear customs into a country?

Thor Pedersen:

Trying to clear customs? That might have been between Ethiopia and Somalia where they were chewing Khat, which is a leaf, a green leaf that you chew. It's a drug, basically, from nature. You look at these people who are chewing Khat, and it looks like they had forty cups of coffee or something like that. They seem quite tense.

They looked at me and they started taking my bags apart, and they found I had a GPS, which I was using to plot my route around the world, and they said that was military equipment. I said it was not.

They found a couple of knives, which I was traveling with and basically I had them to cut rope or cut an apple or something, but, again, they looked at it and said that was military equipment and they got real suspicious, real fast, and they just took everything apart.

Then they guided me away from the road, and over to sit with some officers, and they were sitting there chewing Khat, and they told me to sit down next to them and I was sitting there in the shade, sitting next to them, just wondering, "Okay, what's going to happen now?"

After forty-five minutes, they said, "Okay, you're good to go." I just got up and I packed my bags again, and I left.

I'd say the hairiest situation that I experienced wasn't necessarily with customs. It would have been a checkpoint in the middle of a jungle in the middle of the night in Central Africa.

I'd been driving, just me and a taxi driver. We were driving throughout the night and we got to these guys, and they stopped the vehicle. There were three of them and they were drunk out of their mind, and they were armed to their teeth, and they were vicious.

From the moment I stepped out the vehicle, I was commanded out of the vehicle at gunpoint, and from the moment I got out of the vehicle and they saw that I wasn't a local person but I was a North European, you could just feel the hate, you could absolutely feel hate coming out of their eyes, and the rage from these men, they just had it in for me.

That was definitely the hairiest situation. Being at gunpoint by angry, emotional, highly drunk adults, that was terrifying. I was there for a good forty-five minutes before, for some reason, one or the other, and I'm not sure I understand why, they just let me go. They let me and the driver go.

The only thing I could do in the situation was try to stay as calm as possible, no quick movements, be as compliant as I possibly could, agree with them, anything hateful they would say about me, just agree with them. Yeah. Eventually, I got out of it.

Guy Kawasaki:

All of this is happening in English?

Thor Pedersen:

This is happening in broken French. I was doing my very best to survive with whatever little French I know.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. Okay. Now let's say, step me through what happens. By the grace of God, somehow you get through customs and immigration, so now you're in the country, do you go and walk around, meet people?

Thor Pedersen:

You always meet people. You always meet people. You meet people on one side of the border, going through the border, on the other side of the border, in the buses, in the trains. This was a people project. This was not a country project. This was all about people all around the world. People, cultures, handshakes, kindness, generosity. People are just amazing.

I set out with a motto when I left home, which was, "A stranger is a friend you've never met before", and I thought it was a really nice motto but it wasn't in any way proven. I probably traveled for a couple of weeks before I had several stories that confirmed that little, "A stranger is a friend you've never met before."

Eventually, I started saying, "People are just people," because this is what I believe. It doesn't matter political affiliation or the color of people's eyes or which God they pray to, if they don't pray to a God at all, or if they have children or not, if they're working or unemployed, people are just people all around the world.

People are driven by much of the same. They dance to pretty much the same songs, the same songs get trendy all around the world at the same time, they watch the same TV shows, Netflix, they play the same games on their phones, they like barbecues, they fall in love, they get married, they go to school, they go to work. People are just people around the world.

My standard operating procedure, as someone once called it, my SOP, would be to get a SIM card as fast as possible. This isn't 1845. We're living in a world where one of the most important tools you can have when you're traveling is your smartphone and if you're online, then you have access to hotel bookings, communication, you can call people, you have online maps, you have everything you need right there in your hand.

I'd make my way to wherever I was going to spend the night. Often, I would have that pre-booked, sometimes I would work it out, sometimes I would just talk to someone on the bus and they would bring me home with them and give me a couch to sleep on or a guest bed.

I would locate the Red Cross and I'd go and meet with the Red Cross. Often, I would be invited to a speaking engagement somewhere at a school or a company. I would have to apply for visas and various documents, invitation letters, sometimes I would need to get new vaccines. What else was going on?

If I had any time left for myself, I was blogging, I was updating social media, I was doing stuff like that. If I had any time left for myself, I would try to go to a national museum and see how much I could learn about the country just sucking in information from the national museum or if there's a beautiful waterfall or a temple or anything nearby that I could visit, then I would go and see that.

Guy Kawasaki:

If I do the math, let's say ten years, that's 3,650 days, divided by 200 countries, so, on average, you would have spent a couple weeks in each country. Is that enough to learn about a people in two weeks?

Thor Pedersen:

No. Absolutely not. There's less than 300 people who have gone to every country in the world at this point, and I would be surprised if any of those would sit down and say, "I have seen the entire world." In everybody's case, except me, they were flying, so a lot of the time, they would be looking down at the planet from high above.

Even me, being on the ground or being across the surface of the ocean or a lake, you have to imagine a red line being drawn through a country, so, let's say, the US, for a second, I came from Canada, and then I entered through to Buffalo and from Buffalo, I made my way to Washington DC, and from Washington DC, I got on a train and I went up to Chicago and from Chicago, I went across the Mississippi River and the Rocky Mountains and I made my way down to California. From California, I headed into Mexico.

Then at a later point, I came back to the US from the Bahamas on a ferry, and I entered Fort Lauderdale I think it was, and so I'm in Florida, and then I'm heading up north up to Norfolk.

I visited sixteen or seventeen states within the US, but in reality, I'm just drawing this thin red line wherever my bus or my train takes me, and if I'm lucky, I can maybe see a couple of miles out the window. I'm really not seeing a lot.

But then at the same time, I would say that imagine buying your first car. You don't know what you're doing. You probably see if there's a steering wheel and if there are four wheels on it and then you're happy.

If you're buying your second car or your third car or your fourth car, then you start to know what to look for. You learn from your mistakes. You learn more and more.

By the time you're buying your tenth car or your twentieth car, you do not need to spend as much time in order to understand the conditions of that car. You bring all the knowledge from all the other cars that you purchased throughout your life.

Imagine me going to ten countries, twenty countries, fifty countries, one hundred countries, at some point, you start removing all the noise, the stuff that people get dazzled by when they enter a new country, and you start to see specifics, you start to see are there sidewalks or not, you start to see what kind of clothes people are wearing. Are they wearing shoes or not? Public transportation, does it look good? Does it go frequently? What does the healthcare system look like? What does the this and that?

You can start to pinpoint what kind of country you are in. You get adept to understanding your environment faster and faster, as you get further and further down this tunnel of countries.

Guy Kawasaki:

Arguably, you may be one of the top 300 people in the world to give advice on how to really visit a new place.

Thor Pedersen:

Yeah. I don't know. I'm happy to give advice. My advice is, so I am an avid hiker, I enjoy hiking, and within the world of hiking, there's the hiker's creed and I do not know it word by word, but I can paraphrase, and the hiker's creed would be something along the line of that you should leave nothing behind but your footprints.

I think we should take the hiker's creed and bring it into the world of travelers. When you go somewhere, if you go on a business trip or you go on a holiday or you go for one reason or the other, then remember leave nothing behind but your footprints. Try to be as invisible as you possibly can. Try to be a sponge when you go into a new environment. Try to suck up everything you possibly can. What are they eating? Try to taste the food.

What did they look like? How did they dress? Bicycles, scooters, the cars, the fields, the buildings, the cities, the shops, just suck it all up, learn as much as you possibly can about the culture and the history, see if you can learn a little bit of the language. Use it every time you possibly can, because people love it. If you can just say two or three words within a foreign language, people, they love that you try. No one expects you to speak the full language. Just give it a go.

Guy Kawasaki:

Like ebelskiver.

Thor Pedersen:

I want people who travel to remember, and this is very important, they have to remember that as soon as you leave your home, you become a guest. Even just going over to your neighbor's house, you're a guest. Especially if you go to someone else's country, you're a guest.

You're not supposed to come there and be opinionated and tell them how things are done better where you come from or they're doing things wrong. You're supposed to come and be polite and you're supposed to compliment people, you're supposed to look for the good and the positive. You're not supposed to go somewhere and tear it apart.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. Okay. In this ten years, what did you learn about yourself?

Thor Pedersen:

That's a brilliant question. I pushed my own personal borders in so many different directions. I generally think that you can measure age in two different ways, the conventional way is to look at the date that you were born and then look at the calendar and then calculate how old is this person? We regularly experience that some people, in spite of their age, seem much older. I think that the way that works is life experience.

Generally, you get life experience as you age, so slowly from ten to twenty years to thirty to forty to fifty to sixty and beyond, and you would expect a certain life knowledge and life experience from someone who is fifty and from someone who is seventy and from someone who is one hundred. Where does that life experience really come from? How do you get on the fast track of life experience?

I can't help to wonder that happens when we are challenged. When are you challenged, you're typically challenged when you're brought out of your own environment where you know everything and then put into a different environment where you have to work out, "How do I get a SIM card here? How do I activate it? How do you get a bus ticket? Do you buy the bus ticket online? Do you do it from a window? Do you do it on the bus?"

You show up and you know nothing and you have to learn everything, and then you accelerate within life experience. I wonder, I left home when I was thirty-four, and according to the calendar, I'm forty-four now, but I wonder if I'm somehow much, much older than that on account of having built up much more than ten years of life experience within the duration of ten years. That's something that I'm still reflecting upon.

Guy Kawasaki:

What do you do after you come back from such an adventure?

Thor Pedersen:

Luckily, my wife is still around, and we're building a life together. That's good fun. We've gotten to know each other really well. She came out to visit me twenty-seven times across the world and we were together ahead of this project but now we're living together for the first time, so that's a really interesting adventure.

I have a book coming out next year. I have a documentary coming out next year. I'm doing speaking engagements. I'm invited to events and to companies and whoever wants to listen to me speak. Then we negotiate a price and I show up and I talk about these adventures and share about culture and the world. That's what's going on right now and that's what it looks like.

I have this adjustment period, which I'm still within. I've been home for just about three months now from something that took almost ten years. You can imagine that the soldiers that we deploy overseas, when they come back home, some of them need some time to settle in. They've been in a stressful environment. They've been in a foreign culture. I've been in every foreign culture. I've been in stressful environment for a very long time.

I don't know how long it will take me to reenter society, certainly, a lot more than these three months that have passed.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. Wow. Can you offer an opinion on where the happiest people in the world are?

Thor Pedersen:

I was listening to a podcast just yesterday, and they were talking to the happiest person in the happiest country. The happiest country right now, according to some lists, is Finland. They found one person who they gave the honor of being the happiest person within the happiest country, and that did sound like a very happy person.

It's an interesting thing, because these Scandinavian countries in Northern Europe, they often rank within the top four or five happiest countries in the world, but then I was in the Pacific and I was in Vanuatu, and in Vanuatu, they claim to be the happiest country in the world, and I said, "Hang on a minute. I thought that was in Scandinavia."

I do some research and I talk to some people, and I found out that there are different lists, there are different ways of ranking happiness and, in some ways, in Vanuatu, they dance a lot, they're very social, they enjoy music, good food, it feels like everybody knows everybody and they seem really happy.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. Because you have firsthand experience in 200 countries, I'd be very interested to know what sources of news you trust.

Thor Pedersen:

Yeah. I have a little bit of difficulties with that. I have found that whichever news media is reporting, maybe they send out a journalist and a camera man somewhere and the camera man, he has his camera focused and pointing at the worst thing within the vicinity of the camera, so it might be a fire or a dead body or some sort of destruction or chaos or who knows what?

In my experience, the camera man is usually safe and what goes on behind the camera might be relatively normal, so while the camera is pointing at absolute chaos, when you look behind the camera, often you will find the taxis are driving, markets are open, school children are walking about.

I have this connection from general media where I feel that these stories that are being covered are important. We need to know about the corruption and about the wars and the conflicts and the tsunamis and the diseases and the list goes on. We need to know about this, but if this is the only thing that we hear about, then that will start to paint a picture of a world that's falling apart and that there's nothing good left within the world.

That's simply not true. I've been to every country in the world that has conflict areas, I've been to every country in the world that has war, and what I've found was that, yes, there is hardship but not for everyone.

What you find more than anything, you'll find ordinary people living relatively ordinary lives, they like music and dancing and food and family and they don't like the rain too much and they don't like getting stuck in traffic. People being people everywhere around the world, so which news do I trust? There's nothing that's really perfect.

I listen to BBC. I listen to the BBC World Podcast on BBC World News. They broadcast twice daily. I think it's a good update to understand what's going on around the world.

But they're not covering everything and they're slightly biased. I would say all media is biased. I think maybe BBC is less biased than others.

Guy Kawasaki:

A real tactical question, vis a vis equipment, I would love to know your recommendations for shoes, phone, camera, computer. Are you Mr. REI? Are you Mr. North Face? Are you wearing alpaca jackets? What's the real tactics of equipping yourself to do this? Or it's all bullshit and you don't need Gore-Tex to travel around the world?

Thor Pedersen:

Yeah. Probably the latter. It's all bullshit. You don't need Gore-Tex to travel around the world. I'm on Team Salomon. That was a coincidence. I went into a store in Denmark three days before leaving home, and I said I needed some versatile footwear, something that would hold up when it was warm, when it was cold, when it was wet, when it was dry, and the salesperson, he handed me a pair of Salomon shoes, and they fit, and I left home with those.

Then once I wore those out, I replaced them with a new set of Salomons, and when I wore those out, a new set. Then I started contacting Salomon and saying, "Hey, look, guys, look at me, I'm traveling every country in the world in your footwear." When I reached about 170 countries, they teamed up with me and I became a brand ambassador of Salomon. I ended up visiting every country in the world only in their footwear.

Equipment breaks, and it can be replaced, and there is a lot of good equipment, there are a lot of good brands out there. I generally think that if you're traveling on a low budget and if you're not hiring guards and fixers everywhere and you're on your own, then you don't want to look too flashy, because you don't want to make yourself a mark for those who have less and for those who are desperate.

I try not to look my best always. It doesn't mean I go for the homeless look, but I just like when things are a little bit worn and not too shiny and not wearing a wristwatch and stuff like that.

I left home with an iPhone and I was actually an Android person ahead of this project but I dropped my phone and broke it, and I had decided to replace it with the newest iPhone on the market in 2013, which should put things in perspective because that was an iPhone 5. I left with an iPhone 5, and it held up pretty nicely. Eventually, it broke and then I got another iPhone, and, eventually, it broke and then I got the third and last iPhone for the project.

As far as telephones and equipment, I was pretty happy with iPhone. That worked for me. I'm sure that there is Samsung and HTC, if that still exists, or whatever else is out there, I'm sure they do just as well.

Guy Kawasaki:

What about a camera? Were you taking pictures or were you just using your iPhone?

Thor Pedersen:

I used my phone for the most part. I did have a GoPro camera, and I was updating my GoPros throughout the year, so the quality got better. The iPhone 5 held up for maybe three years or something like that. That was a great deal of countries. More than one hundred countries with the iPhone 5, which, unfortunately, doesn't have the camera quality. Now I have an iPhone 13, and there's a huge gap between the video quality and the photo quality. That's just the direction of technology.

I'm a little sad to look at the old photos and see the quality of that, knowing what it could have been if I had left today.

Guy Kawasaki:

Are these photos going to be published somewhere?

Thor Pedersen:

I ran social media throughout the entire project, so a lot of these photos, certainly, were posted on Facebook and Instagram and X, as it's called today, and many other places. I was blogging throughout.

We are making this documentary right now, so we'll have this full feature film out next year. We've been working on that for four years, and that's going to include some of the photos and some of the video that I have from going around the world.

I don't know. Maybe I'll make a coffee table book at some point, and I'll pick my best photos from around the world and see if anyone wants to have a look at those.

Guy Kawasaki:

In this documentary, and this book, it's not like you ever had a crew documenting you. Right? This is all first-person?

Thor Pedersen:

Yes. It's all first-person. The last four years of the project, I was working in close collaboration with an award-winning film director from Canada. His name is Mike Douglas. He flew out to film me while I was in the Pacific, so I was in Marshall Islands and we spent three days together.

Then the pandemic broke out, so we didn't see each other for a bit, and he told me to film as much as I possibly could. He said, "Film when you're frustrated, film when you're angry, film when you're happy. Just film, film, film."

I did that, and then he came to see me in Fiji at a later point, and then I went around to several countries and returned to Fiji, and he came to film me again, and then he came to Sri Lanka and filmed me and joined the ship with me from Sri Lanka to the final country, which was the Maldives.

We have all of that covered really well. The last four years of the project, we have everything we need and more. It's the first six years of the project where I really wasn't filming a lot. Yeah. I get a lot of heat for that.

Guy Kawasaki:

You were busy. A friend of mine, who has also been on this podcast, is Rick Smolan. Rick Smolan is the guy who did the day in the life of US, Australia, Russia. He followed the woman who was going across Australia with camels. He has experience in this kind of stuff, if you ever want to talk to him. His name is Rick Smolan, S-M-O-L-A-N. Check him out.

Thor Pedersen:

As it turns out, Denmark has an Adventurers’ Club, so there are these Adventurers’ Clubs around the world and there's a chapter in Denmark called the Adventurers’ Club Denmark. I was recently invited to come and speak at their clubhouse during one of their meetings, and I'm hoping that one day, I can become a member.

All of these guys, they don't have much more than one hundred people at one time. That's where they capped the membership. All of these guys are crazy people who go out with kayaks or camels or this or that.

Rick Smolan, he sounds like he fits right in.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah. We've had crazy people, and I mean that in a positive way. It sounds like when you were making some of these border crossings, it was just as dangerous as surfing a 100 foot wave.

Thor Pedersen:

There was some crazy stuff out there but you have to consider the volume. The distance that I covered within this journey is akin to going nine and a half times around the planet or going once from the planet and all the way out to the moon. I traveled some considerable distance.

If nothing is going to go wrong across such a distance and every country in the world and over the course of almost ten years, then you have to be the luckiest person on the planet.

Of course, I have some stories but here's the thing, if we were to talk about bad things from the project, then we would maybe be talking for days, because there's a lot of volume and I can certainly share some stories with you, but if we were to talk about the good stuff, but we would be talking for months and months, because there's been so much more of that, and I think that's just the nature of people around the world.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's a good way to end this podcast. Total upbeat about the goodness of people, because, as you say, media only covers the bad stuff. Nobody ever says, "Oh, family had a happy dinner. Update at 11:00PM."

Thor Pedersen:

Yeah. That is true. There's so much good stuff going around the world, and the only cameras there are from the phones that people are holding.

Guy Kawasaki:

Holy cow. That's one hell of a story. Ten years, no flying into the country, visiting every country in the world. Wow. I can't say I could do that. Let's face it, we're on this dot in the universe, and we're all interconnected.

By the way, Madisun and I have a new book. It's called Think Remarkable. It reflects what we've learned from interviewing over 200 remarkable people like Thor, as well as our own experiences in business. In my case, forty years in tech. Please check it out, Think Remarkable.

Let me thank the remarkable people team, Jeff Sieh and Shannon Hernandez, incredible sound engineers. Madisun Nuismer, a co-author and producer of this show, not to mention the drop-in queen of Santa Cruz, Tessa Nuismer, ace researcher and writer, and backing us up, doing all kinds of miscellaneous and important work, because you have no idea how much work is involved in making a podcast, and transcripts and everything work.

Anyway, the rest of the team is Luis Magaña, Alexis Nishimura, and Fallon Yates. This is the Remarkable People team. We're on a mission to make you remarkable. Until next time, mahalo and aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply