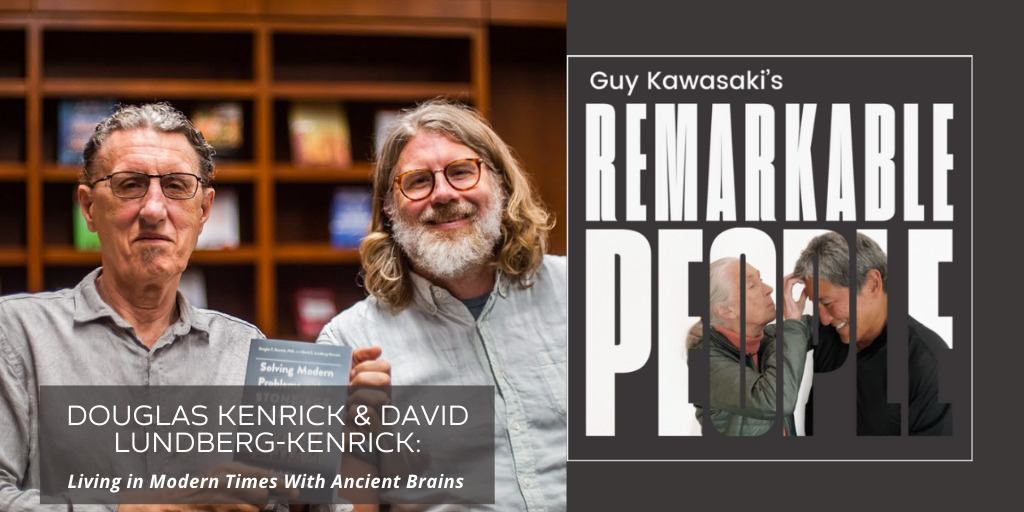

Today’s remarkable guests come in a pair…father and son. Their names are Doug Kenrick and David Lundberg Kenrick.

These two remarkable individuals have come together to co-author a book that explores the intersection of modern technology and human evolution and how our stone-age brains still influence our behavior today.

With Doug’s background as an evolutionary psychologist and President’s Professor of Psychology at Arizona State University and David’s experience as the Creative Director for the Department of Psychology and film production, these two bring a unique and insightful perspective.

In their book, Solving Modern Problems with a Stone-Age Brain: Human Evolution and the Seven Fundamental Motives, they delve into the fundamental motives that drive human behavior and how they can be applied to today’s challenges.

Don’t miss this opportunity to hear from two experts in psychology and evolution and learn how they are solving modern problems with a stone-age brain.

Please enjoy this remarkable episode with Douglas Kenrick and David Lundberg-Kenrick: Living in Modern Times With Ancient Brains!

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Douglas Kenrick and David Lundberg-Kenrick: Living in Modern Times With Ancient Brains:

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People. We're on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is a remarkable dynamic duo, father and son. Their names are Doug Kenrick and David Lundberg-Kenrick.

These two remarkable individuals have co-authored a book that explores the intersection of modern technology and human evolution and how our Stone Age brains still influence our behavior in the present day.

With Doug's background as an evolutionary psychologist at Arizona State University and David's experience as media outreach program manager at Arizona State University, these two bring a unique and insightful perspective to the table.

The name of their book is Solving Modern Problems with a Stone-Age Brain: Human Evolution and the Seven Fundamental Motives. Don't miss this opportunity to hear from two experts in the field of psychology and evolution to learn how to address modern problems with our Stone Age brains.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People. And now, father and son, Doug Kenrick and David Lundberg-Kenrick.

I want to start with a very foundational question, which is about social psychology, evolutionary psychology, whatever you guys call it, about methodology. And it seems to me that many of the studies, if you were being a wise ass, you could say it's interpreting results from a bunch of college students trying to get credit or making pizza money and being extrapolated to all of humanity.

Men don't care about such and such but care about looks, or women are the opposite, or you name it. And it could be that many of the things that once it appears in The New York Times, that's a long way from peer-review by psychologists. So how do we interpret the reporter's interpretation of a psychological study done in a lab someplace?

Doug Kenrick:

So I would say any single study you want to be skeptical about, but what we try to do is we have these techniques called meta-analysis, for example, which just looked at a whole bunch of different findings on the same topic and asks, "Did they produce similar results?"

Now, that might simply be that all college students have the same, so we also look across methods. Lately, psychologists have been looking across cultures. In our book, what we did is we basically went and read literature on anthropology.

So we're interested in the question of... We have this Maslow's pyramid that organizes our book and says that there's seven sets of problems that people need to deal with. And we wrote a social psych book with Bob Cialdini in fact, and we have a similar structure in that book, but there's these seven sets of problems.

Our ancestors needed to survive, they needed to feed themselves, and not get bitten by a snake. They needed to protect themselves from the bad guys. They needed to make some friends and keep those friends. They needed to get some respect, they needed to find a mate, and then they needed to keep that mate, which some of us have learned is a slightly different problem.

And then from an evolutionary perspective, they did all of those things. Those are developmental motivations that unfold in order to care for offspring. And now, when we wrote this book, so we know a lot about social psychology having written a textbook on it, but we also delved into the literature in different fields to try to find out, what's the constant?

So what exactly, if you were a Yanomami or you were someone living on a little island in the Philippines that was a horticulturalist society with no radio or television, or if you were living in the jungles of Africa, anthropologists have studied these remote societies and they're different in many ways, but there are some commonalities that they share.

They have that same to-do list as we do. They have to survive, they have to make friends, they have to get some respect, they have to find a mate, they have to care for their families, and so do we. The interesting question though, it relates to your thing, it's the same motivations we have, but do the old school solutions, what's wired into our brain, do they work in the modern world? And the answer is sometimes, but sometimes not at all.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

I just want to, just to add to this, going back to your question, Guy, this question of, are these studies all done with college students? That's a big concern, that within academia as well is. And I think actually, dad, one of your biggest early hits was looking at marriage studies all around the world to see what things are true all around the world.

Because it turns out the things just happened at ASU's campus might be cultural, but if you see something all over the place, then there's a pretty good chance it's universal.

Doug Kenrick:

Yeah, that's an interesting connection. So be being an evolutionary psychologist, especially twenty, thirty years ago when the field first started, because I was someone, who like you, I know you jumped majors. I didn't start as a psych major, I started as a biology major and then I thought of transferring to anthropology.

And so I got interested in biological evolutionary aspects of human behavior, and it was a great shock to find out that some people regarded that as some kind of a right-wing political plot to justify the existing order. And I was a long-haired hippie guy. My god, I don't want to be associated with a right-wing political plot, but I do want to be associated with finding out the truth about human nature.

I gave a talk at the University of Michigan many years ago, about the time that you were out there proselytizing for Macintosh. And I was young and I gave this talk and I mentioned some findings we had that suggested that social psychologists a long time have said that men are interested in younger women and women are interested in older men, and there's about a two-year discrepancy.

But with my friend, Rich Keefe, we collected some data showing that's not exactly true. It turns out that as men get older, they become interested in progressively younger women, relative to their own age. So a twenty-two-year-old guy and girl or man and woman are both interested in the same age, roughly around that age.

But you get to forty and now the men are interested in a younger woman, they're not interested in a peer. And even when women get to sixty, they're still interested in guys like sixty-five, seventy, even though that's a very thin pool to be fishing in.

And so we found that and when I mentioned those findings and said basically that over the lifespan, women continuously are interested in older men, but men get progressively interested in younger women. And somebody stood up in the back and he was from New York, which I am too, and he said, "That's just due to American culture."

So we went out and we collected data in societies all around the world. And we even got my friend Rich Keefe, who's married to a woman from the Philippines and we went to her little teeny island called Poro and got marriage records from 1920 and 1930. And it turns out that as you got further from American society, older men were more likely to marry younger women.

And in some sense that question, does this apply to college? It's a good question and it forces us to go out and sometimes get better data to answer the question

Guy Kawasaki:

As an aside, let me make a statement that after you're reading your book, I am so glad that I did not become an anthropologist, that is a high-risk profession, is what I concluded from your book. Is the gist that our Stone Age brain is just not equipped to deal with modern problems.

Can you just explain this Stone Age brain that is at fault, if you will?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

I think in a lot of ways it is. We focus on the ways that it's not equipped, but the thing, if you're going to eat when you see food, you have mechanisms in your brain that are going to keep you from starving to death, but you also might overeat because those mechanisms are designed to have you eat as many high calorie foods as possible.

And it's the ways that our brains are not perfectly suited. Those are the situations where it makes the most sense to as people come in and make active corrections to our lives to try to match.

Doug Kenrick:

But a lot of the mechanisms are not mismatched. So for example, in your book on wisdom, you talked a lot about your family, you actually gave a speech I think to the Palo Alto High School, if I'm remembering correctly. You did the David Letterman backwards list, and the first thing you said to them was, "Keep your friends and family close."

That worked for our ancestors and it also works for us. So it isn't all mismatched, but the trick is to figure out when you find yourself having this powerful passion, this leading you a direction that in the modern world ain't working out, that's when.

When we talk about a guy, Walter Hudson, he got to 1,197 pounds. I might have made those last couple of digits up, but it was well over 1,000 pounds. So in this case, our ancestors could have never done that because they didn't have access to that much food and they had to go get the food. They couldn't just sit in a bedroom and have somebody bring them food.

And so sometimes there's a mismatch, sometimes there's not. And the trick is to learn when to go with your feelings and when to not, when you want to suppress and you want to use psychological techniques to manage those impulses.

Guy Kawasaki:

As you point out, that's the trick, but what is the trick? Before you get to be 1,000 pounds, How do you know that your ancient brain has taken over and is defeating in the modern environment?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

I think a lot of times we know, like I know when I'm eating food that I shouldn't be eating and I still eat it. And the same as we talk within the book about not just food, but about how we have these mismatches across friendships and dating type things and career things.

And I think a lot of times, the trick is once we know how do we actually either adjust our behavior or our environment to not allow ourselves to eat all the cookies, like I will do if I have a box of cookies in front of me. And a lot of that comes down to classic behavior management sort of things. Hiding your cookies in the forest.

Doug Kenrick:

It’s called stimulus control. Basically, it's easier to control your environment than to control your appetites. And so if you have a high incentive value food in front of you, if you do, like I did during the COVID pandemic and buy a whole bunch of chocolate covered cherries and nuts because I thought we were going to starve and put them on the counter, you're going to get a potbelly. My pants being tight told me, "Hey, we got a problem here."

And so then the intervention is artificial, actually, then you really do need to learn something about the findings of psychology and not just evolutionary psych, behaviorism and cognitive psychology have a lot of wisdom in there, but you got to learn it.

A lot of the people who you've interviewed, I noticed, they're basically in the game of trying to teach people a trick, a trick like Milkman's book, Katy Milkman, she talks a lot about we're aware we want to change, but it's not that easy and we need artificial props and we need to learn.

Guy Kawasaki:

I think this is a modern day application of this, which is I freely admit I'm addicted to my iPhone and I would sleep next to my iPhone and check it several times a night.

But I have figured out, talk about changing your environment as opposed to your behavior, if I charge it two or three rooms away, I won't get up and go get it in the middle of the night.

Doug Kenrick:

That's a perfect example.

Guy Kawasaki:

So is that an example of putting the chocolate in another place?

Doug Kenrick:

Exactly.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

Very much. Yeah, that is a perfect one. It's also a good one if you find that when you wake up in the morning, you check it, rather than getting out of bed.

It's a good way to get yourself out of bed because if you wake up and you're like, "I want to know what people are saying about me on Twitter," you go and you seek it out. So that's actually a perfect one.

Guy Kawasaki:

Is this what you refer to as the naturalistic fallacy?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

The naturalistic fallacy is more the idea that just because we have a natural desire to do something, that that means that it is either ethically good or even good for us.

And so the naturalistic fallacy would be more like the idea of, "Oh, if I want to eat something I should, if I'm angry and I want to hit someone I should." And so those sorts of things turn out to not really be so good in most situations in modern life.

Guy Kawasaki:

Dave, you just described half the people in California.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

I digress.

Guy Kawasaki:

If we were having this interview 1,000 or maybe 10,000, maybe 100,000 years from now, do you think our DNA or whatever's inside us is going to catch up and figure out that our brain needs to evolve and not do this?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

So yes. Yes. Even when you think about the Stone Age brain, it's not like everybody in the Stone Age was perfectly adapted to the Stone Age.

Our ancestors probably were more adapted. And there are probably people out there today that are more adapted, even perhaps than you or I, but the question is, "Do I want to go out without a fight? Do I want to let the fact that my brain might make me want to eat cookies more than someone who's a little more well adapted, allow me to be pushed out of the gene pool? Or do I want to correct and say, 'No, let's keep me a part of this'"?

Doug Kenrick:

There's another interesting aspect of your question, I think, which is I actually thought no, rather than yes, to tell you the truth, because I thought that, I think that technology certainly evolves faster than our brains do. In fact, that's part of our technology now.

Our brains haven't evolved, it's only in the last 150 years that most of the things around us have existed. So even this nice bicycle I have, you couldn't have gotten it 150 years ago. You couldn't have gotten an iPhone 15, 20, I don't know how long they've been around, you couldn't have gotten this Mac that I had. The one that you were pushing back in 1983 was just that little square box.

And now I've got this amazing machine which allows me to talk to you as if you're in the next room. So a lot of this stuff is new and yet we adjust to it.

And I think that in some sense, human beings, we're a cultural animal. And so we learn, we develop tools that help us pull the coconuts down from the trees, rather than just evolve to climb better. And I feel like I think that's what's going to happen.

And assuming we survive, I think that we will actually learn. And Dave, you and I have talked about this, we talk with our kids sometimes, who are very techy and they're attached to their devices. Are there ways, and Guy, I'd be interested in your question, are there ways to use technology to help us fight technology?

Little sub-programs I can put onto this thing that I do know they exist, but it'd be nice to make them really attractive so that it says to me, "Doug, you said this morning you wanted to work for two hours on writing, and now I see you've read The New York Times headlines for two hours. Do you want to keep doing this or would you rather go back to your writing?" And maybe even give me... Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

At least there wasn't Fox.

Doug Kenrick:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

So you mentioned Maslow's Hierarchy a few minutes ago. So what's wrong with Maslow's Hierarchy in the modern age?

Doug Kenrick:

Do you want to answer that one?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

No, you go for it, dad. This was research that my dad and Steve Newberg and Mark Schaller and Vladas Griskevicius just did. So I think you should explain it.

Doug Kenrick:

This actually was a very controversial idea. It got into The New York Times twice. It was one of my three minutes of fame, and some people got a little annoyed at this, but I'll tell you what the idea was. We looked at Maslow and turns out Maslow was an early evolutionary psychologist, which his advisor was Harry Harlow.

Remember the monkeys with the cloth and wire mothers? Harry Harlow was arguing against behaviorism and the idea that every social motive is secondarily derived from eating or drinking.

And what he found, he did that research on contact comfort, but Maslow was his student and Maslow expanded that idea and said that not only are we not simply physiological hungers and thirsts, but we have social needs that are separate from those and we have the need for affiliation.

I forget what he called them, but basically... Then we also have a need for esteem, which we would call status. And then he thought we moved to self-actualization, to developing our own selves. And his ideal was someone, and it sounds very good to an educated person, being off somewhere, painting your own painting, playing your own music and not worrying what other people think. And that's the part that-

Guy Kawasaki:

That's the other half of California.

Doug Kenrick:

That's right. No, I'm sure he was extremely popular in California, but probably still is.

But where I would differ from Maslow is that in two ways, one is, I think that he missed out on fifty years of other evolutionary psychologists come along and reminded us that organisms are designed to reproduce.

And again, naturalistic fallacy doesn't mean that's the best thing to do is to have twenty kids. I admire you had two kids and then you adopted two kids, which I think is a much better way to go than just thinking, "I want to replicate, have 100 kids. But that's a separate ethical question.

But Maslow paid no attention to reproduction. And if he talked about sex at all, it was like as an annoying biological need that you could probably have gotten out of the way with masturbation, then move on to playing your guitar and doing some higher thing just for yourself.

And we disagreed with that and said, "Look, after you get to esteem, what do you do? Then you use that to find a mate and then you need to keep a mate." So we took self-actualization off the top of the pyramid and put in finding a mate, keeping a mate and caring for your family. And people, when that was in The New York Times as the Idea of the Day, these letters, hostile letters were sent to The New York Times and sent to the dean at ASU saying, "How dare these people mess...?" It was like we had torn apart a crucifix or something like that. It's says, "How dare they mess with Maslow's sacred pyramid?"

And I could see the reaction because self-actualization became an ideal. It's a good thing to do. It's good to develop your talents. It's good to be into philosophy and music, but what I would argue is that we don't do that for non-social motives.

It isn't like we go play our guitar off by ourselves. We develop those talents so that we can connect more with people. And if you're a male and you're like Diego Rivera, you develop those painting talents and it has some non-small consequences for your mate value. He would not have gotten Frida Kahlo if he wasn't a great painter. And so we basically argue that yes, self-actualization is a real thing.

Human beings do want to develop their own unique potential, but they want to do it so that they become valuable to other people and they become valuable mates. That's the biggest difference.

The other thing I would say, one other difference, and Dave will tell me I'm talking too long, but speaking of California in the 1970s, I think Maslow's ideas were a little too psychology of the 1970s and 1960s, too self-centered. Kind of like, "Why would the idea be that I make me, that I devote my life to me?"

And even Maslow didn't really believe that. If you look at his examples of people, they were people who were great because they helped other people. They were like Eleanor Roosevelt. They were people he admired and he admired them not because they were off playing their guitar in a room by themselves.

Guy Kawasaki:

Have you ever heard of the Japanese concept Ikigai, I-K-I-G-A-I?

Doug Kenrick:

That rings a bell, but go ahead and tell me about it.

Guy Kawasaki:

It's this concept that you find your life calling and whether it's making pottery or samurai swords or, to me, my life calling is podcasting, which is another way of saying self-actualization.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

But you put the podcasts out. Right? It's not like you're just recording podcasts with people and then storing them in your attic. And the same thing, even with someone who's making pottery or making samurai swords.

I would think that someone who makes those and then gives them or trades them with the people around them is going to be having a more fulfilling life than someone who just... I don't know. I could see making pottery and keeping it in your house being really fun, but I think the giving it back is a big part of it.

Guy Kawasaki:

I have a fundamental question about pyramids, whether it's yours or Maslow. And it seems to me that the pyramid is a shaky metaphor because it implies you build the base, then you move to the next level, then you move to the next level. And one of the implications of that is, once you build the base, let's say the base is filling your nutritional, clothing, security needs, so you got that base, then you can move on to a higher thing.

But my observation of life is you may have that base, but that base is not necessarily permanent. So it's not like you can say, "I checked that box off, now I can go just work on pottery in a dark room for the rest of my life." So why do we continue to use the pyramid as the metaphor?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

I'll be honest, we have spent so much time debating whether or not to make this a pyramid, and even the original title of the book we had talked about calling it... Because we really like the seven fundamental motives. I think my dad and I both agree these are great things that everybody's concerned with, but then we were like, "Is it climbing the pyramid?

Because then people are going to try to jump to the top. Is it building the pyramid?" I actually think like a prism where you view through it and you see all the things at once would be a better metaphor. But I don't know, I guess pyramids are the thing.

Doug Kenrick:

I have a different answer. My answer is that actually our pyramid isn't precisely a pyramid. We in fact have overlapping triangles so that when you move to the next level, the other one is behind and it's still there. In fact, in our pyramid, we don't have the base go all the way across. We have another triangle and a little bit of space on the side.

So it indicates that all throughout your life, you're never going to get over the idea of survival. If there's a threat to survival, our mechanisms for self-protection or whatever, for getting food or getting away from a snake are going to come in. If there's a threat to my friendship, it isn't what I'm going to say, "I'm now playing my guitar, so who cares?" Then I'm going to jump in and try to do something to maintain the friendship.

So my argument is that ours is not a pyramid in the sense of you do... In fact, even Maslow thought this, but he got misconstrued over the years. He didn't even make the pyramid, incidentally. It was an organizational psychologist whose name I've forgotten who made up the pyramid.

He just had a hierarchy, but Maslow didn't believe that the motives go away, nor do we.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

I would say that the one thing that I do like still about the pyramid metaphor is the idea that the upper layer layers are less likely to collapse if you've got those foundational layers.

Guy Kawasaki:

True, true.

Doug Kenrick:

And you do need, developmentally-speaking, that is the way you go through life, that basically a kid when they're first born, they're not concerned with status or mating or any of those things. And then a kid, when a kid goes into preschool, they start to become concerned with affiliation, but they don't really care.

They'll go around with a dirty diaper all morning playing with their friends because they're not even thinking about how they're being evaluated. And then suddenly around maybe age seven or eight, the desire for esteem kicks in.

So these things kick in, but the others don't go away. When I start to become concerned with status, I don't stop being concerned with my friends. In fact, sometimes there's conflict between the different motives, so status and affiliation.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

That's true. That is one of the things that I think it's really tricky to balance all of them. And so a lot of times we have to choose, and I think this is one of the things that always make cinema and art so compelling, is seeing people choose between these different motives.

Someone who has to decide between protecting their loved ones or protecting themselves. So yeah, I think these are big questions.

Guy Kawasaki:

I would make the case that anyone in Hollywood is making a choice between status and caring for your family. I don't see a lot of good parenting coming out of Hollywood. Right?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

Unless maybe Pixar. The people who are there might be more doing family stuff. And Pixar for kids always do well.

Doug Kenrick:

Toy Story.

What was the one about the kid that went up in the balloon?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

Oh, Up.

Doug Kenrick:

So they're out there.

Guy Kawasaki:

Unless they're telling me that I should look to Kanye West as a role model for parenting.

Doug Kenrick:

There's very few people who will argue that, probably not even Kanye West, I'll bet. So why we wrote this book, originally we started writing a different book because Dave went to NYU's film school.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

I did. And then when I heard about this pyramid, I actually, I was like, "This is a great breakdown of what themes are interesting in entertainment." I love seeing people have to choose between these sorts of things.

Even when you mention Kanye, I immediately start thinking he's good at demonstrating status. And then he has kids, but now he's in this mode where, and we see it very publicly, his relationship has broken up and now he's got to choose between his own status, from that, and taking care of his kids with his ex. It's compelling. And I think this is what we like in life, is we like seeing this, and we like it in art, is seeing people try to figure these things out.

How do you balance this? How do you maintain your status and how do you keep your family together, even in Hollywood?

Guy Kawasaki:

It would be a really interesting test if you give people these seven components and say, "Okay, each of you build your pyramid."

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

What we actually have started suggesting to people is think about ways you can achieve each of these goals. What's the biggest challenge?

So, Guy, for you right now, if you think about survival, self-protection, friendship, mate acquisition, mate retention, kin care. Oh, I missed status. First of all, which of those is occupying your mind the most?

Guy Kawasaki:

Parenting, 99 percent.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

99 percent parenting. And now, what about your kids? What do you think your kids are trying to figure out? How old are your kids, by the way?

Guy Kawasaki:

They are thirty, twenty-eight, nineteen and seventeen and they're not thinking about parenting, at least I hope not. They may be thinking about managing their parents but not parenting their own.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

That is a big one, actually. I know my dad's lab did some asking people what is really important and parenting ends up being really high. And then taking care of not just kids, but other family members. Really big one for a lot of people.

Doug Kenrick:

You had brought up before evolutionary psychology, and a lot of the early research was on mating and digression. And so I collected some data with Aurora CO and a large team of fifty something collaborators in thirty-five countries.

And we asked people the question Dave just asked you, in terms of, what are your motivations right now? And one of the things we found that was really interesting was that mating-related motives were very low, even for college students, believe it or not.

College students care more about maintaining their romantic relationships than they do about finding new ones. And they also care more about families.

Now, there are some slight differences. Males care more about finding mates than females do, but it's not like even for a college-aged male, it's the top of his heap. The biggest things that people care about is they care about their friends and their families.

That's what people are thinking about on a daily basis. And that's interesting because you'd think if you read some of the literature, if you read people's perceptions of evolutionary psych, everybody's thinking about getting laid all the time. And even for college students, they're thinking about those, maintaining.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

People do spend a lot of time thinking about maintaining their relationships when they're in relationships. That's an important one. So that's what your kids are probably thinking about their friendships and they're probably thinking about you.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, you sure you're not subject to self-selection in that you're only giving these surveys to psych students? Is the ASU football team involved in these things, too?

Doug Kenrick:

The first survey we gave, there's a guy, and I'm forgetting his name, but he is a co-author on our paper, but he works with Tony Robbins and he wanted to have a more theoretical approach to coaching people. And so he has this gigantic list of people.

And we sent the first questionnaire out to his list of people and they were people who were above twenty-five years old. The mean age was in their forties. It was a wide range. And so that was our first sample where people came back and said they're concerned with their families. And first I thought, "Well, of course they're probably older people who have young children."

Then we did it in other countries, and a lot of our subjects were college students, but some were not. We also got samples that were from outside of the college population, working adults.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah. I'm going to go really detailed in for a second here. So you explain this concept of go tit-for-tat and then turn nice. And I want you to explain that because I think that is so powerful and I'm being a little bit of a hypocrite here because I can certainly do the tit-for-tat part, but not necessarily the turning nice part. So will you explain that as an evolutionary concept, to be happy and succeed and successful, et cetera, et cetera in life?

Doug Kenrick:

What do you think, Dave?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

Are we talking about the ideal strategies for cooperation versus conflict?

Doug Kenrick:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

So a lot of times, people have been running these simulations of, what is the ideal way to cooperate? And being nice, one of the best ones is you always start out being nice, but then if the person you just interacted with wasn't nice, then next time you're not nice to them.

Doug Kenrick:

But then the next step is, and this is what computers do better than humans. So Guy, your concern is correct. The computers do much better if they switch back to being nice because they do something annoying to you and then you do something annoying to them. That can be a trap where it's not going to stop.

But it actually turns out that if you switch back and say, "Look, you were nasty to me this one time and I reciprocated, but now I'm going to be nice again." That's hard to do. That requires a kind of a zen discipline in some sense. But if you do it, it's a great strategy.

It's a hard to beat strategy, because if you keep reciprocating negativity, then you've lost the relationship and you've lost any benefits. But if you keep being nice to someone and let them screw you over, then you're being suckered.

We talk about this as one of the obstacles to being nice, which is maybe people will exploit you, but the tit-for-tat and then switch back to nice turns out to be, it's a good strategy, but it requires some self-discipline to do it. If somebody's done you wrong, it's hard to be nice to them after that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Is this a good algorithm for parenting, too?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

Actually, no, because the thing is for parenting, and you guys have done some research on this, too. So a lot of the ways the study, this is using like prisoner's dilemma type games, where the ideal outcome for you is not necessarily the same as the ideal outcome for the other person, but you both do better if you cooperate. I'm just going to explain it real quick because I'm half explaining it.

So essentially, it'll be the type of thing, if two people have to confess to a crime, if you confess and the other person confesses, you both go to jail for ten years. If neither of you confess, you both go to jail for a year. But if you turn them in and if you confess and they don't... I'm doing this backwards.

Doug Kenrick:

No, you got it wrong. No, if you confess, then you get off the hook and they go to jail for twenty years. So it's the prisoner's dilemma. But the prisoner's dilemma has to be modified when you're talking about kin because if I'm at a prisoner's dilemma game with Dave, he shares half my genes and so I get half of his benefits.

And so we in fact did some modeling that showed that, in fact, the number of situations that are dilemmas are actually lower when you're dealing with kin because you get 50 percent of the benefits back. So if I give Dave 100 bucks, it's really giving Dave fifty bucks in some sense because fifty of it's going to my common genes, from an evolutionary perspective.

So when you're dealing with your kids, yes, the rules, the normal rules, it's one of the problems that psychology for a long time used a kind of marketing metaphor. This idea that it is all about game theory and that you want to maximize your rewards, like the classical economic man model.

That turns out to be a great rule if you're trading stock options on Wall Street and you're dealing with strangers, but it even turns out that you've been in business context, you don't deal with your coworkers that way. You don't always say, "You do something for me. I want the best possible deal I can get out of you and I'm going to give you the least possible thing I can give." They're going to say, "I'll deal with somebody else rather than this nasty son of a bitch."

And so we actually like, you recommend in your book, be nice. That's a good strategy. It turns out that people who are nice to their coworkers go up further because I want you to be my leader if you're the nice person.

So there's a different rule for coworkers. And then when it comes to your children, you're never going to get anything back, really. And so it's basically, it's an evolutionary one-way street. We give them resources. I give Dave resources and I hope he uses them wisely and passes some of them to his kids, but he still hasn't paid me back for that NYU education and I'm not holding my breath.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

So just to jump in real quick and try to redeem myself from my terrible explanation with the prisoner's dilemma. I did want to say, so like my dad was saying, his group had research on people do better in the prisoner's dilemma with family.

So these tit-for-tat strategies that have been done with computers running these games, there's actually... Athena Aktipis's lab did some really interesting studies showing that if the algorithms have a chance to move, to decide who they do business with, rather than having to be randomly selected, to always have to do business with another randomly selected algorithm, the ones that would just be very nice and then also move to be closer to the ones that would be very nice, those did even better than the ones that had a tit-for-tat strategy, I believe.

And so it actually turns out a lot of times, even in business, the best thing is just always be nice, but then surround yourself with other people who do the same.

Doug Kenrick:

And well, her strategy was called Walk Away. That actually turns out to be better than tit-for-tat. If you're in an interaction with somebody and they appear to be exploitive, find another partner, and then what will happen is those exploitive people will be left out on their own.

Guy Kawasaki:

Another part of the book that I found so fascinating is the, I hope I repeat these studies correctly, but this concept that when an attractive research assistant appears on the scene, male skateboarders try riskier tricks. That is so interesting. And first, did I get that right?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

I'm going to try this one because I've talked to Von Hippel about this and they are less likely to bail. So essentially, there's a point when you're doing a trick and you might realize, "I'm not going to land this," and you can bail and run off your board, or you can commit, and if you commit, you might land the trick or you might wipe out.

And they went to a skate park where most of the skateboarders were men. They went up to men to ask them, I don't know if there were also women there skating, but they talked mostly to men. But they asked guys and they either would have a woman, an attractive woman, or a guy go up and say, "Hey, could you show me a trick that you are currently working on?"

And when the woman would ask, the guys would be much less likely to bail, so they would wipe out more, but they would also land tougher tricks because they would commit. And there's a lot of really interesting studies because then they also even took testosterone samples from the guys, and the guys, their testosterone would go up, which would make them more likely to ran land tricks but worsen math problems.

So they actually think it might even be that guys can't even calculate risks as well when we get the testosterone boost.

Doug Kenrick:

Oh, what they found is there was a correlation between how high your testosterone level went when the attractive women came and how risky you were. And so that was a very fun finding.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, looking at it from the woman's point of view, do you think that the attractive female is looking at the males who are taking more risk and consciously or unconsciously they're thinking, "Oh, this male takes more risks, he's braver, stronger, et cetera, et cetera. So better provider."

But my question would be why wouldn't the female be thinking, "This dumb ass is going to get killed and leave me as a sole provider?" So what's going on in the female brain?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

Well, it might be that for women, as they're walking around town, everybody around them is falling off of skateboards. So they might just think, "This is how guys act all the time." But the guys who land the tricks are demonstrating a sort of true signal of competence of physical prowess and balance and things like this. And it's a good question. Has anyone ever looked to see if a guy who wipes out on a skateboard and then asks a woman out, if that works out for them?

Doug Kenrick:

No, I don't think that's been done. But there is research that does show that women are attracted to guys who can establish some kind of dominance over other men. And so at the skateboard park, being the best skateboarder, that's the way to dominate the other guys.

But there's a very interesting question that you're raising, Guy, and I'm not sure the answer to it. It sometimes depends on whether women are looking for short-term or long-term. So for example, women are actually more interested in less flashy guys for long-term relationships.

So we actually did a study with Jill Sundie, who's who is also a student of Cialdini and Vladas Griskevicius is another member of that same team with Bob. And what we did is we asked women to evaluate guys who were driving either a really flashy car, the kind that Guy Kawasaki likes or who were driving a car, a...

Guy Kawasaki:

Or a Prius.

Doug Kenrick:

Yeah, or a Prius. All right? Or it was actually something like, yeah, it was a Honda. It was a nice model, middle class Honda, but it didn't say, "I'm risky and I'm flashy." And both guys had a good job, and the guys who drove the flashy car were regarded as more attractive for dates right now, for short-term relationships, but for long-term relationships, I believe the guys who drove the Honda Civic were considered a better bet in the long run.

And people would advise their sister, "Go ahead and go on a date with the guy with the gold Porsche," but when you're going to settle down and get married, they trust the guy that's driving the Civic more.

Guy Kawasaki:

I want you to know that I have one of each of those kind of cars.

Doug Kenrick:

Oh, you do? You've got all bases covered.

Guy Kawasaki:

I got all the bases covered. If I may be so bold, because I think my listeners should definitely read this book, we go into these seven areas. At the end of every chapter you give, these are three or four tips for the seven areas.

Can you just give us, for survival and dealing with bullies and getting along and getting ahead and finding true love and staying in love and having a great family. Can you just give us the sixty second, one minute evolutionary psychologist summary of those areas?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

So for survival, one of the biggest challenges these days is things like eating too much or a sedentary lifestyle and setting up your environment. We talked about that earlier in the show, but that's a really powerful one.

Keep the foods you don't want out of the house, but also the other side of environment, setting up your environment is making healthy options really easy, so have the healthy foods nearby. And also, even think about ways to just take a few extra steps every day. These are things people have probably always heard, but they work.

Doug Kenrick:

Again, it requires a discipline. So both Dave and I, we live about a mile and a half from campus. We live in the same neighborhood and we have offices down the hall from one another. You can see my bicycle over here. We both gave up our parking stickers and that forces us to either bike or walk to work every day.

And so that's the kind of thing you can do, is basically you can make it easy because you don't have to decide every day. We're tired most days. And so if you force yourself to have to walk or bike to get something, then that helps.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

So I also want to add one more thing. So some of the things we're mentioning right now are going to apply to all seven because they're basic behavior management things, social support, seeking social support for these sorts of things is really useful.

I've started doing this thing after my dad was reading Katy Milkman's book and we were talking about Liz Dunn's research on giving people money because it makes you happier. I now give my kids money after every week that I don't eat processed sugars.

And that gets them to really support this. And there's some research on that. But basically, just find ways to get the people around you to say, "Hey, you want to go for a walk?"

Doug Kenrick:

Make public commitments. So the next chapter, why don't we switch chapters and I'll do the next one? The next one's on avoiding bullies and barbarians, it's self-protection. And micro plunderers, who are the people that are nickel and dimming, the human equivalent of mosquitoes that take so little that we almost don't notice it, all these little fees.

And so one of the things we talked about, if you're really talking about real dangerous stuff, the anthropologists who we talked to went into the jungle and met some people who just killed some telephone linemen. The advice from Kim Hill, who was that anthropologist, what he tried to do was not look like a threat.

They basically took off almost all their clothes. I thought he said they got naked. He later told me no, he just went down to his shorts just to show there's no weapons hidden here.

And so when you're in a novel place and you see a bunch of dangerous young men, you don't want to look like a threat. You've mentioned teaching once in a prison, and I did, too. And I remember when I walked into that prison yard, I made damn sure I didn't make too much direct eye contact.

I didn't stare down any of those guys, and I just looked like a nice, "Eh, I'm a laughing guy." And so that's one thing.

Another thing we talk about in that chapter is join together with other people to deal with what we call micro plunderers. So for example, sometimes groups of consumers get together. There was a utility company, I'm forgetting where they were, when solar power came in., What they wanted to do is raise the minimum monthly charge so that you couldn't get away with going to zero.

You still had to pay something. And that got out in the news and one person couldn't fight it, but one person went out and gathered together hundreds of other people and went to the newspapers. So in the same way that we would gang up to protect ourselves from the bad guys coming over the hill in the ancestral environment, we can gang up to protect ourselves from those modern micro plunderers.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

Yeah. I want to just jump in real quick here on the micro plunderer idea because one of the things, I have this podcast, Zombified, where we talk about how we're manipulated by things like technology and things.

And a lot of times, I think it's tempting as a human to think if there's an app that is making me unhappy, like the news feed from CNN or Fox News or whatever that's scaring you, that the people behind it are deliberately trying to trick you or make you unhappy. And it turns out that these days, a lot of times there's just things where the algorithms don't quite match up with our evolved mechanisms.

And so just thinking about ways to team up, even with the people who make those sorts of things and try to always think of ways to make better apps and things like that is actually a really good thing. Because a lot of times the big bad guys of today aren't really people, they're just ideas that need to be improved.

Doug Kenrick:

They're algorithms that say if I read an article about a former president who shall not be named, which is very tempting for readers of The New York Times, The New York Times fills their newsfeed with all these scary stories about white nationalists and kinds of people who don't read The New York Times.

And it's almost like they're giving advertising, but they're not doing it on purpose. They're doing it because we click the damn button. And so one of the things that we recommend at the end of chapter is, look, when there's some bad news that keeps coming your way, just unsubscribe.

So I actually give to a lot of liberal causes to be honest, but I really get annoyed when people who probably read Cialdini's book, they're using tricks to get my money. Even when they're on my side, I don't like that. And I don't like it when every day I open up my mail and somebody who's a good person running against-

Guy Kawasaki:

Nancy Pelosi texted me twice today.

Doug Kenrick:

Yeah. And it's always, "There's bad things are happening." And I'm sure that the Republicans get the same thing on the other side. "The Democrats are going to let all these people in from foreign countries that are going to rape your daughter."

And what we get is, "The Republicans are going to steal grandma's social security check and kill people who have abortions." And what I do is I try to stop, when they scare me all the time. I just unsubscribe. I don't want it. And even The New York Times, I try to limit myself to one look a day. I don't want to just keep hearing the same. And I also try not to press the buttons about he who shall not be named. I try to read the good news.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

I also want to say in the era of Twitter and social media where we all create news, resist the temptation to spread bad news, just post a positive thing every day. And if it doesn't get as many retweets as a negative would've, that's okay.

Doug Kenrick:

That's actually a good heuristic for all of us because I like... There's a guy, Brad Bushman, he does a social psychology textbook, too, I believe in. He's on my Facebook friend list and he's got probably thousands of Facebook friends, but every day he posts several jokes.

And I realize I really like that because a joke is just as attractive as a nasty newsfeed. There's just something attractive about that.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

We're going to jump to getting along. You got to make time for real life friendship. There, boom.

Doug Kenrick:

Let's talk about that a little more, Dave, because I think that's a good chapter in the sense of all of our chapters open up with stories. And that one opens up with the story of a little Jewish kid who was living in Nazi occupied France and trying to avoid the Nazis.

And so he had no friends. His parents wouldn't let him make friends with people because they were afraid that he would reveal himself as Jewish.

And they moved out to a little farm and they lived in a chicken coop. His name was Daniel Kahneman, who had no friends as a kid. And then as an adult, he had a very famous friendship which got him a Nobel Prize with Amos Tversky.

And so what we talk about... It's also interesting that they became friends because they were both at the same university in Israel, but they came from different countries and they were in many ways different, but they shared a common interest in psychology. And so I think one of the pieces of advice in that chapter is, look for people that share your interests, look for people that actually are similar to you because that's a good basis of friendship.

And also, even when somebody doesn't look like they might be exactly like you, if you delve around, you'd actually find that they do.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

You look for similarity.

Doug Kenrick:

And then a third thing that Dave was just saying, make yourself useful. Friendship doesn't have to be about going out and drinking or partying or whatever, or just good old buddy stuff. It's fine to do that.

But also, my best friendships have come, Cialdini and I have been friends for fifty years and we've helped each other. He helped me more than I helped him, but I was actually his first graduate student, yeah, many years ago.

So getting ahead, why don't you tell, who's the person that we talk about in getting ahead, Dave?

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

Actually, so this is a great one. This one we actually talk about Bob Cialdini as our story because he had a thing where he was going to be a baseball player, and he tells the story so great because he was about to sign the contract with a recruiter for a farm team, and the guy's pen wouldn't work.

And then they were walking to get a new pen and the guy says, "Listen kid, are you smart enough to go to college?" And Bob was like, "Yeah." And he was like, "Are you smart enough to do well in college?" And Bob was like, "Yeah." And he said, "Go to college, because..." He didn't go into more of this., But as Bob tells the story, he says, look, the idea was he would've been an okay baseball player, but instead, which was his dream, his dream was to be a baseball player, but instead, he went into the field of psychology and he found a way to help other people.

And by doing that, he had more success than he would've had pursuing his dream, most likely, his childhood dream. Because for one thing, he rose up to be like the Willie Mays of influence, but also this was a thing people needed. And so our big things are find ways to help other people fulfill their seven fundamental motives, that's really the main... And pursue a career in that.

And when you're in whatever career you're in, help your coworkers achieve things like that.

Doug Kenrick:

In that chapter, we also talk about going for prestige rather than dominance. Go for respect. Learn some skills that people need. You talk about this in your book as well. Learn a skill that other people need. You can learn a skill that is a talent that people don't need. That's not so good. That's like being a good athlete.

The truth is there's 1,000 to one odds that you're going to go from being a high school athlete to actually being a highly paid pro. And there are some occupations that it's a lot... Every year, the US News and Worlds Report, I think, publishes a list of the jobs that are most in need of people and that are jobs that are good.

I think a computer programmer or something now is one of the... Isn't a programmer, it's something like that, is they say it's a good job. It'll get, it's not going to make you Willie Mays, but it'll make you a living.

The next chapter, Finding True Love, we talk about finding mates. The case story there is a woman named Sharon Clark who was swept off her feet by this charming guy. She was working at a, what do they call those things? Not a garage sale. What do they call these things? A swap meet up.

And this guy drives in with this big, beautiful Cadillac and wearing gold jewelry. And he had a lot of fancy stuff he was hauling in a trailer, and then he started giving her flowers, a very charming... And so she married him. And it turns out that she discovered he disappeared with her mother's belongings, with her belongings, and with the money that she had used after she sold her house as she was going to run off with him.

And his name was Giovanni Vigliotto. And when she found him, she found out that not only had he screwed her over, he had 104 different wives and he'd done the same thing to each one of them.

And so that's one of the interesting things about the modern world, and it's the online, there's some modern examples of this, guys online who pretend to be one thing, and then they exploit, they get into the woman's checking account.

And so one of the piece of advice we have there is to shop locally, get together with people who you trust and know and who your family trust and knows. And yeah, I realize that goes against the grain now because people are meeting online.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

Yeah, especially if you're looking for long-term. If you're looking for short-term, just go to the skate park and find the guy who doesn't fall.

Doug Kenrick:

And what about maintaining relationships…

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

This goes back to one of our big themes, which is help your partner achieve all of their needs as well. This idea of, and I won't go into the whole story, but we talk about Madame Curie and Pierre Curie, how they work together.

And I think a lot of times people think about, "Oh, your partner is just somebody you," I don't know that people actually think this consciously but, "It's somebody you mate with." But just remember that it's also, this is somebody that can help you get along, help you get ahead, help you make friends, and you can help them. So do that.

Doug Kenrick:

So Dave's big single piece of advice, I always like for almost all of these things is, rather than trying to help yourself in this domain, go out and help somebody you care about or it's one of your coworkers. That's probably a fabulous suggestion.

Our final chapter is called Family Values and it's about caring for your kin. And in that chapter, one of the things, is that even in the modern world, it pays to keep your kin as close as possible, because that's one of those old, we talked before, what things are not mismatched, it's not mismatched to love your family because your family loves you back and they're willing to put up with a lot of your crap. You can get away with stuff.

I've actually been doing some research with Amanda Kirsch. One of the things we know is that biological relatives don't kill each other, but what we found, which is interesting, they do hit each other and they yell at each other. And why do they do that?

Partially because your kids know they can yell at each other and hit each other and they're not going to terminate the relationship and the other person's not going to kill them, which isn't always true with other people you meet.

So again, keeping your kin close is good. If you can't maintain real contact, that's where technology comes in handy in a good way, maintain virtual contact. And I actually think things like Zoom and the thing we're using right now, where you can actually see the people, that's a massive improvement over... When I was a kid, the telephone, I hated the telephone because you can't see people's expressions. All you can get is a little bit of feedback.

And then when you get to text messaging, it was even worse. All you get is a few words. You can't even see the facial expression.

David Lundberg-Kenrick:

Yeah. I just want to say one quick thing about the Amanda Kirsch study. It's about siblings are more likely to sort of fight, but it's not designed to injure the other person. Some of it is you practice your fighting, but part of it is you practice your fighting, but also kin are more likely to call each other out harshly on ways they are messing up.

And so the other part of that is talk to your kin about the decisions kin, and it doesn't just mean brothers and sisters, but your family, your cousins, talk to them and they'll give you real feedback most likely and listen to it.

Doug Kenrick:

They'll be honest. They will be honest with you. Yeah. So the other thing at the end of the book, we come back and talk about a woman named Oseola McCarty. And she's a great story because a lot of people, and Dave, you pointed this out, Dave pointed out to me that he goes on Reddit and some people seem to treat evolutionary psychology as a formula for if we have selfish genes, then the way to be is selfish.

And it turns out that even Dawkins didn't say that. As a human being, that's not a good strategy, but we regard as a hero, not Genghis Khan, who got a lot of his genes into future generations, but was pretty brutal along the way of doing that.

We have, as our role model, Oseola McCarty, who didn't have children of her own. She did care for her family, but she was a beautiful story. She was born in 1910 or 1908 in that rough era, and she had to drop out of the sixth grade.

She was an African American woman living in Mississippi, I believe, had to drop out in the sixth grade to help her aunt who had become ill. And she started doing people's laundry and she never went back to school. And she would make ten cents a shirt cleaning and pressing a shirt.

And over the years she never bought a car. She never bought a colored TV. She had a little old black and white TV for a few years and she would roll her groceries from the supermarket in a shopping cart. And she lived in a humble home and didn't have many expenses.

And she goes into the bank and she ended up having what looks today, it was 1990, but if you're correct for inflation, she had roughly close to $450,000 as I recall, which was a lot more money than somebody with no bills, no car. And so her banker said, "How do you want to invest this money, Osceola?"

She said, "I don't need it. I want to give it away." And she gave it, this woman who dropped out of the sixth grade to help her family, she gave her money to young African American women to go to college, and she won the Presidential Medal of Honor from Bill Clinton back when it meant something.

And she really was a hero. And she lived a nice ripe old age, she lived to ninety-one. People respected her and she lived a fulfilling life. And that I think is a model. Do nice things for other people and you'll feel good about yourself and other people will want to be near you.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's a wrap for today's episode of Remarkable People with Doug Kenrick and David Lundberg-Kenrick. Thanks for tuning in as we explored the fascinating world of evolutionary psychology and how our Stone Age brains still shape our thoughts, behaviors, and experiences.

We hope you enjoyed the discussion and learn something new. Be sure to tune in next week for another enlightening episode of Remarkable People.

Until then, keep your mind curious, your evolutionary psychology sharp, and be like Oseola McCarty.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People. Thanks to Peg Fitzpatrick, Jeff Sieh, Shannon Hernandez, Luis Magana, Alexis Nishimura, and the drop-in queen, Madisun Nuismer. Mahalo and aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Leave a Reply