Esther Dyson is the executive founder of Wellville, a 10-year national nonprofit project aimed at achieving equitable well-being for people.

She is a leading angel investor focused on health care, open government, digital technology, biotechnology, and outer space.

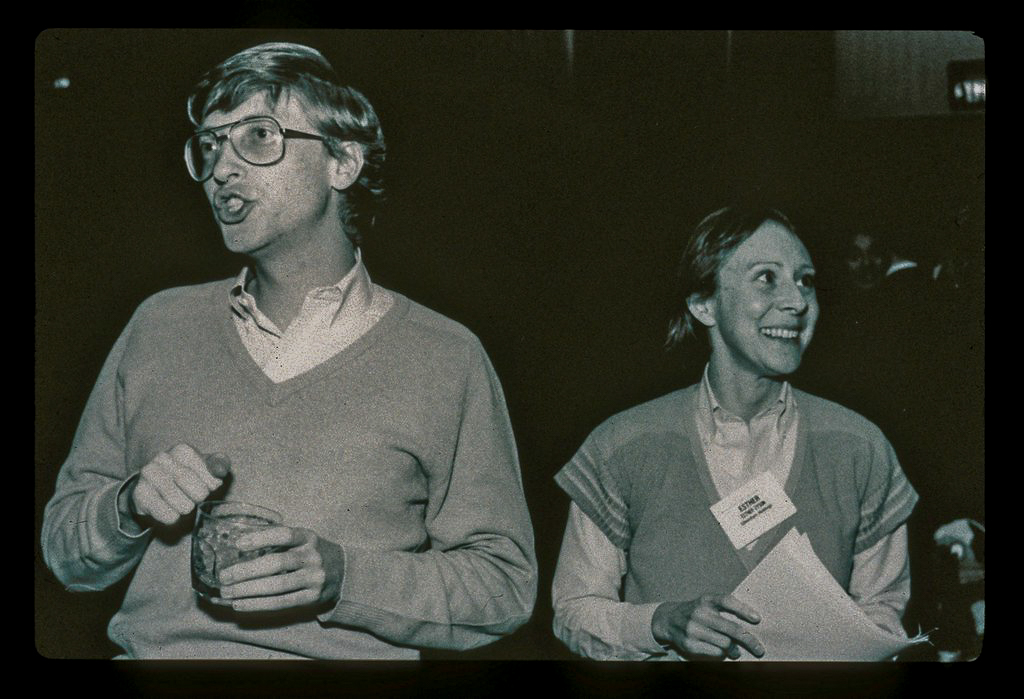

During the personal computer days, when I was Apple in the 1980s, she was the most powerful and prestigious analyst in the business.

She was a king and queen maker. You prayed that she’d cover your product in her newsletter, Release 1.0 or invited you to her conference, but you feared a negative review or getting drilled on stage.

People like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates, if they didn’t fear her, at the very least, realized they better suck up to her. She may not even realize how intimidating she was back then.

Esther is the daughter of physicist Freeman Dyson, and mathematician Verena Huber-Dyson. She obtained her bachelors in economics from Harvard, She is the author of the bestselling book, Release 2.0: A Design for Living in the Digital Age.

Enjoy this interview with Esther Dyson!

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Esther Dyson:

Guy Kawasaki:

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People.

I'm on a mission to make you remarkable.

Helping me in this episode is Esther Dyson.

She is the executive founder of Wellville, a ten-year national non-profit project aimed at helping people achieve equitable wellbeing.

She is a leading angel investor focused on healthcare, open government, digital technology, biotechnology, and outer space.

During her personal commuter days where I first met her, she was the most powerful and prestigious analyst in the business.

Truly she was a king and queen maker. You prayed that she covered your product in her newsletter, Release 1.0, or invited you to her conference.

But you also feared a negative review or getting drilled on stage.

People like Steve Jobs and Bill Gates if they didn't fear her, at the very least realized they better suck up to her. She may not even realize how intimidating she was back then.

Esther is the daughter of physicist, Freeman Dyson and mathematician, Verena Huber-Dyson. She obtained her bachelors in economics from Harvard.

She's the author of the best-selling book, Release 2.0: A Design for Living in the Digital Age.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People, and now here's the remarkable Esther Dyson.

What is the end goal of Wellville?

Esther Dyson:

It's a project, it's a ten-year non-profit project so it ends at the end of 2024.

But what we're doing with the communities is like raising kids. We want them to build their own capacity, we want them to have their own intrinsic motivation. We're not like a typical philanthropy that pays people to do things that we think are what they need.

We are coaches helping them do what they think they need. We can certainly ask them awkward questions and say don't you want to scale this more? Or what if you had more resources? Or why don't you collaborate with these people over there instead of competing with them?

But in the end, their goal is to build capacity and build sustainable institutions and social fabric in their own communities. Our goal is to use them as examples to get other people to copy us. Because the way we want to scale is not by applying our own resources, which are limited, but by getting people to do the same things.

The message in a sense is you can do it yourselves you don't need people like us. You need other people to show you it's possible, but these people in Muskegon they're great, but we didn't go find the best people in the world, they didn't all go to Harvard.

They're just good people with a vision and with the courage to do something and you can do that too.

Guy Kawasaki:

Are you familiar with the experiment that John List provided in Chicago for grade school kids? He's from the University of Chicago and they had this several year preschool program, amazing results.

I interviewed him a few weeks ago and he said, "Well, one of the things we learned is that yes, if you hire the thirty best teachers you can find in Chicago, the program is great. What happens when you need 30,000 teachers?" Is that what you're trying to avoid?

Esther Dyson:

What he said is true, that a community can find training for its teachers and have expectations of them, you're right. A community has got what it starts with.

It's just like your family you don't really pick your family. But by treating them well and instead of trying to construct your kids like a carpenter, there's this wonderful book by Alison Gopnik, The Gardener and the Carpenter.

Instead of trying to construct them, you just need to nourish them to grow and turn into the best. If your kid wants to be a football player don't try and make them be a violinist. If they want to be a carpenter, don't make them be an artist.

It's taking the assets you have and making the best of them and understanding that you need to invest for the long-term rather than just do short-term stuff.

I may tell you later about the quadrant chart or Nancy Strickler's Bento Box. Your goal ultimately is to be a good ancestor, not to fix everything yourself.

Guy Kawasaki:

Fundamentally, do you think you're going to avoid the problem of scaling?

Esther Dyson:

No.

Guy Kawasaki:

Because that was John List's problem, scaling the Chicago experiment.

Esther Dyson:

Wellville will avoid it because we're not going to try. We hope that we can encourage the world to spread it for itself. We're working interestingly in Muskegon for example, which is there are five communities and I work most closely with the people at Muskegon.

We're working not just with local people, but also with local branches or entities like the YMCA, the Goodwill, the Boys & Girls Club. We hope to use them as vectors for some of what we're doing.

Guy Kawasaki:

If somebody wanted to be devil's advocate, wouldn't they say of course Muskegon can succeed, they got a mentor, they have Esther Dyson mentoring them we don't have it.

Esther Dyson:

That's a very good question. In some way, well everybody in this business we applied for the MacArthur Grant. The 100 million in change not for a specific thing, but just we'll give you some money to do what you're doing.

They asked, “Why is your team so amazing? What are their backgrounds? Why should we give you guys $100 million?” That was for us the toughest question, because you're right you don't need us. You do need to see that it's possible for people like you to do it. We're trying to help the first ones get out there and show themselves.

But no, it's not we ask the world's most amazing questions, the questions I ask are things like imagine you had enough resources to really fix this problem, what would you do? You wouldn't grow by 10 percent.

Interestingly, the YMCA which was doing the diabetes prevention program in Muskegon is now doing it online throughout the state of Michigan.

No, they don't have millions of people yet, but suddenly you realize oh, we could do this.

Role models are so important, whether it's a kid with a teacher who matches his culture or somebody seeing that oh yeah, there was a schoolteacher who did this once, or there were a bunch of people at Boys & Girls Club, and they used these Oura Rings to measure their sleep.

Then the kids started feeling that they were empowered, and we could do that too. People don't say the baseball team need the... Coaches help, but it was the baseball team that won it wasn't the coach.

Guy Kawasaki:

Would you say that this is the most satisfying work of your career?

Esther Dyson:

Absolutely. I'm learning so much and I'm not motivated by love and sweetness, I'm really motivated by curiosity on the one hand and just this sense of stupid problems shouldn't exist. It's one thing to cure cancer, that's really great. But so many of the problems around racism and education and health are stupid problems.

They're problems that we know how to fix them, we don't know how to get ourselves to fix them. But they don't require rocket science, they require some investment up front in education, in good parenting, in schools and childcare workers and stuff like that. We don't need a scientific revolution.

We might need a little bit of a political revolution. Because this stuff does need to be paid for and it's worth paying for.

Guy Kawasaki:

Based on your experience with this, what's your advice to Silicon Valley tech successful founders? What should they do after they've done everything?

Esther Dyson:

If you have five billion dollars there's another set of things you can do. But if you have a few hundred million or you have twenty million to spend for the next ten years, what are you going to do? Find a problem that is worth solving where you can have a real impact.

Don't try to solve every problem, get focused. In our case we focused on five small communities. It may be that you want to develop a particular solution to something, it may be something in your neighborhood. I hope it's not forgive me, your very expensive college that you went to that you now want your kids to get into.

Look beyond yourself and your own grandchildren. Look at the communities and the world your grandchildren are going to live in, and then focus on that. It may be health, it may be the environment, it may be charging stations worldwide, it may be getting politically engaged in something, but do something that's meaningful that will have a long-term impact. Don't just hand out money and feel good about handing out the money. Would you pay someone to run your company?

No, you want to build it yourself. In the same way, don't pay other people to maybe have an impact and feel good about it, actually get engaged.

If you're so smart that you earned this 200 million in the first place, you should be smart enough to do something pretty special next time around as well.

Guy Kawasaki:

Would you say that Bill Gates has done it right or wrong based on what you just said?

Esther Dyson:

He's a perfect example of somebody who has a lot more than 200 million, and he's mostly done it. He's focused on things. Things have gotten complicated between him and Melinda.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah there's that.

Esther Dyson:

But he's definitely made a wonderful transition from a guy who just wanted to compete in the marketplace to somebody who really wants to solve some of the big problems. You can argue about almost any institution of size has it become too bureaucratic or whatever.

But yeah, he's not handing out money and feeling good, he's addressing serious problems and convening people and talking about solutions and so forth. It's the difference between a day trader, you trade stocks, and you make money, but you don't really make any difference to the companies whose stocks you trade.

In the same way, you can hand out a lot of money to philanthropies, but if you don't really check whether they're having an impact, that's what your job should be, figuring out what will have impact not merely donating money and feeling good.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well then when you see Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson race off into space, one of your favorite subjects, are you full of admiration or are you just nauseated?

Esther Dyson:

Neither. I share their interest in space and I think space is important. Seriously, I think it would be handy to have a backup planet on Mars at some point, really.

It's curiosity and exploration and a desire to solve stupid problems and hard problems that has gotten us as far as we've gotten. You could argue we're actually a species full of addiction and political messes, and how far have we really gotten?

But we've gotten amazing tools, including the ability to go into space, learn more about the universe and scientific curiosity, I've got it. I love it, and my parents were both scientists. I would say that Jeff Bezos's... People do different things with different motivations.

I think his motivations behind Blue Origin are in some ways better for mankind than those behind Amazon, though Amazon for better or worse employs millions of people. Millions, yeah I think so, one way or another including the truck drivers that are maybe not on the direct payroll.

It's made the world more efficient, it's also got some toxic aspects. Richard Branson's motivations are a little more business related. One of the space industry's big problems when it started was it was just a bunch of billionaires and not very good managers, but then they got serious about business.

The two Elon Musks to me are such a wonderful example of the guy who runs Tesla who's out of control, smokes dope on TV or whatever. Then the guy who shows up at NASA with Gwynne Shotwell and Gwynne has said to him beforehand Elon, you just keep quiet.

These guys are serious government people, don't do any of that funny stuff.

She runs SpaceX and it's a very serious company that has government contracts and actually gets things up into space, and I think that's pretty amazing. I don't think space is a distraction. It's definitely like most science it's meandering but then things happen.

A lot of what we're learning in the space world is precisely about the circle economy, about recycling, about 3D printing is the epitome of what you need to do in space, because you can't just call headquarters and ask for more you have to do it locally.

The same way hydroponic, all these new urban agriculture hydroponics. Logistics is way too expensive and resource intensive versus distributed manufacturing, however you want to call it, and distributed agricul-

Guy Kawasaki:

I think you may be one of the few maybe the most qualified to pronounce judgment on the next question, which is, do you have greater regard for Steve Jobs or Elon Musk?

Esther Dyson:

I don't quantify it, but they're just two different people. Maybe it's worth telling a story. When you asked me about the whole people in Muskegon and people in other places, do you need an amazing mentor blah, blah, blah.

I was traveling in Russia of all things with Ashton Kutcher on this little tour organized by Alec Ross in the State Department! We had Jack Dorsey and John Donahoe from eBay and Mitchell Baker from Mozilla. We also had Ashton Kutcher who was invited had a film shoot couldn't come, and then at last minute he had three days free, so he decided to come.

The first amazing thing about that was… have you ever been chased by screaming girls?

Guy Kawasaki:

No.

Esther Dyson:

Anyway, wonderful. Traveling with Ashton Kutcher even in Novosibirsk, screaming girls.

Anyway, we did a session with some kids in Novosibirsk, first with the high school kids and we asked them questions.

Half of them said we want to immigrate to the United States. We said why? Oh, people there are happy, they work hard it's such a great place we want to go there. The next day we were with the university audience, much more formal.

We were up on the table and the first student, we discovered later that they had been totally rehearsed the day before said, "Mr. Donahoe, you are the epitome of the American dream, can you tell us how your life became so exciting?" John gave a little answer. Ashton was fidgety and finally said, "I've got a better idea, we're going to ask you questions. I want to ask you again, how many of you want to immigrate to the US?"

Quite a few of the kids raised their hands and the professors in the back, “This was not on the schedule.”

Then Ashton who as he played Steve Jobs in a movie said exactly the same thing to them. He said, "You don't need to go to America to smile, you can stay here and smile. You can stay right here in Novosibirsk and work hard. You can make amazing..."

Anyway, he did this Steve Jobs impersonation, it wasn't it was Ashton, but it was just amazing. It was one of those moments where you feel, I'm privileged to be here. I think of him sometimes vis-a-vis our communities. No, you don't need to go to Harvard. If you're in Muskegon, you don't need to go to Detroit.

You can build something amazing right where you are. That was one of my treasured moments. Someday maybe I'll get Ashton Kutcher to talk to them.

Guy Kawasaki:

But wait, but that doesn't answer my question. Do you have-

Esther Dyson:

Steve or Elon? I knew Steve I've met Elon. Steve he insulted me a few times the way he insults everybody if you don't live up to his-

Guy Kawasaki:

Join the club.

Esther Dyson:

Like so many brilliant people he was really hard to deal with, but he created amazing things, and so is Elon. Elon is less of a specific designer more of a company designer, and they're both sui generis. It's like asking which is your favorite kid. We don't do that, we don't say which is our favorite Wellville community either.

Guy Kawasaki:

If we go back in time, so we were making the rounds in the mid-eighties, right?

Esther Dyson:

Yeah in kindergarten that was fun.

Guy Kawasaki:

How has technology evolved compared to how you thought it would evolve back then?

Esther Dyson:

Technology has become so basic that dealing with technology means dealing with fundamental human nature problems, which also means politics, it means allocation of resources.

It's like in some sense, whether you're a nation or your meta platforms, you're Facebook, you owe your community some voice in how they are governed. You also owe them some governance. You can create a store and you can have specific rules in your store, and you can charge people to show up and so forth. But if you create something big enough that it's fundamentally a public platform, you need both public governance and representation of those governed.

It's awkward because the transition isn't easy. The more power something has the more transparency it needs to undergo. When people talk about the metaverse, they focus way too much on the technology and not enough on the rules of the game.

How are you going to control this place? What rules are going to be there? What are the rules for leaving and entering? How do people or entities get favored? I think of all these.

The reality is I was the founding chair of ICANN, which is the governing body for the domain name system. Our basic mission was to make sure that governments didn't control the internet. They by and large don't but that's beginning to change. The domain name system is less relevant now as search engines and the internet is not URL based as much as it used to be.

But at the same time, what we did not manage to do was to get genuine public representation. The domain name system now is mostly governed by lawyers, registries, registrars, marketing people, it's become something of a protection racket. I'd much rather give up some money than give up my voice. It could be a lot worse.

But if you think that there won't be the equivalent of advertising, if you think that because NFTs are not physical there won't be hierarchies of people who have more NFTs who have more privileges, we're constructing a virtual economy as well as a virtual living space, if you like.

But that virtual economy is also going to inflict inequality unless we're careful about it. The inequality comes from lack of education, lack of access, lack of privilege. The world should not be governed out of its own, how should we say, variety and creativity.

But at the same time, I don't want a world where everything in the various metaverses I visit is controlled by shady business interests.

In theory it's easier to leave, but in reality, again, we're an addictive society, we tend to want more, and business interests cater to our desire for more. Short-term desire is addiction, long-term desire is purpose.

But short-term desire is much easier to feed and how should we say seduce. Long-term desire needs an individual sense of agency and understanding of what they want to do for the long-term.

Guy Kawasaki:

I interpreted what you just said as Mark Zuckerberg would be the last person in the world you'd want running the metaverse right?

Esther Dyson:

Precisely. Unfortunately, just because they're called meta platforms doesn't mean they're going to run the only one. But they are a very instructive model because in fact they are a metaverse for billions of people.

The fact that it's not immersive yet, the fact that nobody thinks when they go on Facebook that they're really somewhere else, it is where people mingle and communicate and spread lies, and sometimes spread the truth and comfort one another and challenge one another and spread misinformation.

It's definitely a place where people live and its governance is pretty pathetic as we've discovered.

Guy Kawasaki:

So you used the word addiction, and I saw a discussion of you at a TEDx talking about addiction. Can you just explain the core of addiction?

Esther Dyson:

Yes. There's dependency, the physical thing you get with drugs and alcohol and withdrawal and so forth and so on. These are chemicals and they have chemical reactions. That's real, and it can be treated partially with medication assisted treatment and so forth.

There are lots of reasons people get addicted, but there's a huge correlation call it a reason between basically childhood trauma, difficult circumstances growing up, and honestly difficult circumstances later. So much of addiction is a reaction to toxic circumstances around you.

But you can get addicted as a mental behavior pattern with all kinds of things that are not chemicals. So you don't have the physical challenges, but you do have chemical reactions in your brain, it's not that kind of addiction is imaginary. Usually it starts with pleasure. Oh, it's really fun to get drunk and you're more relaxed and you feel good, or getting high.

It can also start just with pain relief. Again, whether it's a drug or something else. It can start with the pleasure of eating food, but it gets to the point where again now comes the behavioral mental part.

You use that as self-medication against anxiety, against difficult circumstances, against feelings of inadequacy, against your parents want you to be a football player and you'd really rather play the violin. You stop getting pleasure, but you need it for relief.

As you get addicted, you lose your sense of the past and you lose your sense of the future. You just get more and more obsessed with this one thing that will give you relief and it's only temporary so it's a very short-term cycle, very unsatisfying and not a pleasure at all. People who are addicted do horrible things to their families they steal, not all of them.

But it changes your ability to think long-term and outside your own immediate despair if you like.

So much of modern business, in some sense to me Robinhood is flat out a gambling business. They talk about democratizing investment, but it's short-term you're not investing.

You're trying to get lucky, and you do get this short-term high even from losing money. We've become a society that's addicted, and it's not just people, community organizations get addicted to short-term grants.

The best thing that anybody said about this is Zephyr Teachout in her book Break 'Em Up. She said profits in a business are like sex in a marriage. They're part of the deal, they're important for sustainability, whether it's producing children or sustaining your business because you make profits, but more profits and more sex don't necessarily make the business or the marriage better, they're not the point of the enterprise or the relationship.

In Silicon Valley often people aren't trying to build businesses they're trying to make exits. I love the idea of sustainable businesses making a profit, paying people, training workers, building, growing, being sustainable, solving people's problems.

But so many businesses are basically just grown to be sold so that somebody can say I got ten times and I'm worth 400 million.

No, the stock you hold is valued by the last investor in at 400 million, but they've got these special preferences.

Again, it's addictive and politicians are addicted to votes and influencers are addicted they want money, they also want this fame that ends up being very unsatisfying. It's something that's destroying our society.

Guy Kawasaki:

What's the solution?

Esther Dyson:

Happy childhoods. Fundamentally, if I had five billion or maybe five trillion, I would impose mandatory parent training. I have to say that as a joke, because I'm a believer in better governance than one lady imposing parent training on everybody.

But most problems you can attribute to people's parents who can attribute it to their parents, so it's really not a question of blame. But if you can somehow get into that cycle and make more children grow up fulfilling their potential rather than being damaged before they get into middle school, that would change everything.

Guy Kawasaki:

Some asshole's probably thinking it's easy for her to say her father was Freeman Dyson. If my father were a world famous physicist and my mother was a mathematician yeah I could have had a good childhood too.

Esther Dyson:

I was extremely lucky. I was lucky, but I shouldn't have to be lucky. More people should be lucky or the government should pay for more people to have parents who have decent jobs so they're not scrambling.

Who have enough money to pay for childcare, who have enough money and time to read books to their kids, who aren't stressed out so that they scream at their kids, who aren't stressed out so that they turn to drugs or alcohol. That's the point. Having good parents shouldn't be a matter of luck, it should be a matter of government policy and society being willing to pay for that.

Because honestly, it's so much cheaper in the end if you don't need to send all these people to jail or pay unemployment benefits and deal with the physical and mental health problems that a challenged childhood creates.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you see some irony in both of us being here discussing this? Because back in the '80s and '90s we weren't exactly thinking that good parenting is the key. We were thinking bigger, faster, cheaper chips, displays.

Esther Dyson:

I think I had a little more sense of some of this even then.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well that's you not me.

Esther Dyson:

I never lived in Silicon Valley, and in New York you just get exposed to much more stuff. In California, you go out to eat and the people in the next table are talking about options or signing bonuses or code or chips. In New York City, you sit on the subway, and you see who are going to their job cleaning somebody's house, or maybe they're a ballerina.

You see a lot more of ‘normal’ people. Though I must confess when I grew up, I was fourteen when I made the astonishing discovery. I thought I know there are people who work in stores, but doesn't everybody else have three months off in the summer like us?

But that was the point at which I did in fact begin to learn more about the rest of the world. Then I went to Russia in 1989 and I discovered a lot about what it means that cynicism, the deaths of despair, the stuff that led to the opioid epidemic in Russia in 1989 had already led to huge levels of alcoholism. The men pretty much felt useless and that's what's happened to a lot of people in this country.

Guy Kawasaki:

This may be too big a question, but can you explain Russia to us? Because I'm just shaking my head. I don't understand how a country that has an economy smaller than California is just telling the world what to do.

Esther Dyson:

That's not explaining Russia, it's explaining how we deal with Russia. It's a matter of history. They were a great world power, they got somebody into space before we did. And that's changing dramatically and it's hard for Russia to deal with.

But they do have nuclear weapons and it's complicated. I learned a lot more about the United States looking at it from outside having gone to Russia than I learned about Russia itself.

Guy Kawasaki:

What'd you learn about the United States?

Esther Dyson:

Partly what happens when people don't trust their government, when there's cynicism everywhere, when the press is controlled. Also, that communism, capitalism, all these things matter less than a system that is trusted and believed in by the people in it, and it goes back to governance. That's what we've lost here in the last few years to a greater or lesser extent.

Guy Kawasaki:

I also saw a thought attributed to you, which I just find fascinating. Which is the advice that people shouldn't take jobs for which they are already qualified.

Now, why do you say that?

Esther Dyson:

That's really good advice if you're lucky enough to be able to follow it. Again, it comes from a place of privilege, but nonetheless if you have the opportunity, because then you can learn something, and you get your employer to invest in you and you become better.

Everything I've ever done in my life has been basically an educational enterprise first of all. Release 1.0 the newsletter, for twenty-five years I got to learn about the computer industry and watch how it was developed.

Everybody would talk to me because either I could help make them famous or I would keep my mouth shut depending on what they wanted. I joined the board of Twenty-Three-and-Me because I wanted to learn about genetics.

I went to Russia to learn about Russia. I have had the world's most privileged life probably, I've traveled to eighty plus countries.

In most of them I've not gone to the museums, but I've known insiders one way or another. I went to visit a dental clinic in Estonia in 1990 where I learned so much about Estonia. The people in the dental clinic were of course government employees, but they also had this little side business offering dental services to people from Finland for hard currency, and their goal was to start their own private dental practice.

That was a microcosm of what was going on in the Eastern block at that time. I went to Hong Kong before everything fell apart there too, which was really sad. So anyway, take a job where they will invest in you, it's the best bargain.

Guy Kawasaki:

With all this travel, do you think that people around the world are more different or more the same?

Esther Dyson:

They're fundamentally the same with a lot of different culture upbringing. It's interesting I was at a discussion with Walter Isaacson and Nicholas Thompson about Jennifer Doudna and genetic engineering and stuff like that.

The reality is you can genetically engineer someone to be potentially a great athlete or great scientist or whatever. You can't do it on demand, but you can definitely improve the odds. But the reality is so many people never get even close to their potential.

We could do a much better job much more cheaply by just helping the people below average reach up to average. The reality is if there hadn't been Bill Gates there probably would've been somebody else who played a similar role. Steve Jobs and Elon Musk in a sense were more special and particular.

But the real shortage is of people who could have been contributors to their families, to the communities and who basically got damaged before they ever had a chance.

The number of people who reached their potential was much higher in the US, now I think it's really sinking. It varies obviously, and cultures vary, but human nature is the same. What the local culture, what the local governance does to it makes quite a lot of difference.

There are so many people who come to America because they want freedom. Now often it's the immigrants who are doing so much more, because they struggle to get here and they feel that they somehow got the upbringing to struggle, and so many people born in the US are just being squished, not by the immigrants, but by their own circumstances.

Guy Kawasaki:

If you wanted to stop job creation you should stop immigration that would be-

Esther Dyson:

Exactly, yes. What we should also do we should price in externalities. We should pay childcare workers more. We should pay teachers more. I believe we should also tax sugar and tobacco and stuff like that.

We do tax tobacco, but the costs imposed on our society honestly right now by sugar, I don't want to get too political, but not being vaccinated is not just about yourself it's an antisocial behavior, and it imposes a cost on the country.

Guy Kawasaki:

Again, you're one of the best qualified people in the world to answer this question. Pattern recognition for successful startups, what do you look for?

Esther Dyson:

The first thing I reject out of hand is someone who says, “I've always wanted to be CEO.”

Guy Kawasaki:

Why?

Esther Dyson:

Because that's not the point, being CEO is not a privilege it's a job. I look for people who say I want to solve this problem. Not even I've got a solution to this problem, because nine times out of ten you learn that your solution isn't that good and you have to fix it and improve it, so you need to be focused on the problem.

Some of the best companies are started by people who didn't know much but were willing to learn. You don't need to be the expert, but you need to surround yourself with experts. In both the things I've done, EDventure Daphne Kis was our CEO, and at Wellville, Rick Brush who comes from Cigna is much more organized.

Actually today he called me and told me, "Are you sure you really want to go to this place? Do they really want you there or are they just being polite because of Omicron and so forth?" It was a good wake up call, and I think they do really want me but I worked harder to check that out.

People need Gwynne Shotwells, they need to be willing to say the purpose of this company is not for me to be its CEO it's to solve this problem. I will start this company to solve this problem but it's not for me it's for the problem. I want to build the best company not have the best title.

Guy Kawasaki:

So that's something to avoid, you got anything that you should specifically-

Esther Dyson:

Yeah, discipline, and the sense of purpose, and the sense of flexibility and ability to deal with ambiguity. Put it this way, I never believe anybody's projections. They're either way too low or way too high.

So they need to know what are we going to do if they're too low, how do we adjust? How do we improve the product? How do we survive? If they're too high, how do we scale without getting out of control? How do we keep hiring good people without losing our culture? How do we create a good culture? A good CEO cares about their people not just their customers.

Guy Kawasaki:

When I talk to entrepreneurs about their projections, I tell them listen, whatever you tell me, I'm going to add a year to your shipping date and I'm going to divide by 100.

Esther Dyson:

You're probably right most of the time. The other thing is, so I'm an angel investor, for every ten companies you remember it ten years later it did something worthwhile. Two maybe you made money or somebody bought them, and seven of them you can't even remember was I really an investor in that one?

Those seven are not failures, they provided the education because you learn a lot more from things that don't work. If you hadn't invested in those seven, you probably would not have invested in the one that actually took off, because you would've been more risk averse. You have to feel comfortable and understand that those seven were not failures, they were simply your education cost.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let's say hypothetically that Esther was to write Release 3.0 subtitle, a design for living in the post-pandemic metaverse. What's that book going to say?

Esther Dyson:

It's going to be a lot about these things, about dealing with ambiguity, about thinking long term and thinking beyond self-interest and how to spread that. That's what Wellville is trying to do. We started out as a health thing and health very broadly defined is what we're about.

But so many people are talking about training AIs. We need to start talking about training little babies' brains not with robots, but with love and tenderness and security.

Again, it's how do you give people intrinsic motivation rather than just force them into discipline?

It's hard, being a parent is hard because you need to nurture and culture and encourage rather than direct and control and again construct a perfect child. Those are the big challenges.

Then getting people to do that on a broad scale and to think long-term about other people. It sounds very theory and abstract, but it's actually very concrete and it's about bringing out people's better nature because they feel confident and purposeful and engaged and secure and they feel needed.

The worst thing in the world is to feel useless. It's worth pointing out in an audience if you disappear nobody will miss you, in a community if you disappear you will be missed.

Guy Kawasaki:

Just to make sure I interpret that, in other words as a performer you're not that valuable, but as a participant-

Esther Dyson:

No, as an audience you're not that valuable. Someone who's got an audience is not as good as someone who's leading a community. Because you want people not just to follow you, you want them to feel the ability to organize themselves.

The point was more the loneliest person is the one that nobody needs. Grandchildren are the best thing for grandparents.

Guy Kawasaki:

Truly my last question is, let's say there's a young Esther Dyson listening to this podcast right now. I don't know if she's at Harvard and bored and listening to podcasts instead of studying, but let's just say it's a young Esther Dyson.

What do you tell her? What's your advice to her?

Esther Dyson:

Always be learning. I learned a lot at Harvard, not in class, I rarely went to class. I got much more serious about learning once I got through college. But if you're not learning you're deteriorating.

Once you get qualified find something else to do, whether it's in the same company or elsewhere. Your role on earth is not to keep producing the same thing, your role on earth, is it's partly to love and have children, but it's also to learn to do new things and to experiment and learn more and teach others.

Guy Kawasaki:

I hope you enjoyed this episode with Esther Dyson.

It's so interesting to watch her transition from king and queen maker in technology, to a much greater horizon for the wellbeing of people in general. There's lots to learn from the remarkable Esther Dyson.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People. My thanks to Jeff Sieh, Peg Fitzpatrick, Shannon Hernandez, Madisun Nuismer, Luis Magana, and Alexis Nishimura.

Until next time Mahalo and aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Leave a Reply