This is Remarkable People. We are on a mission to make you remarkable.

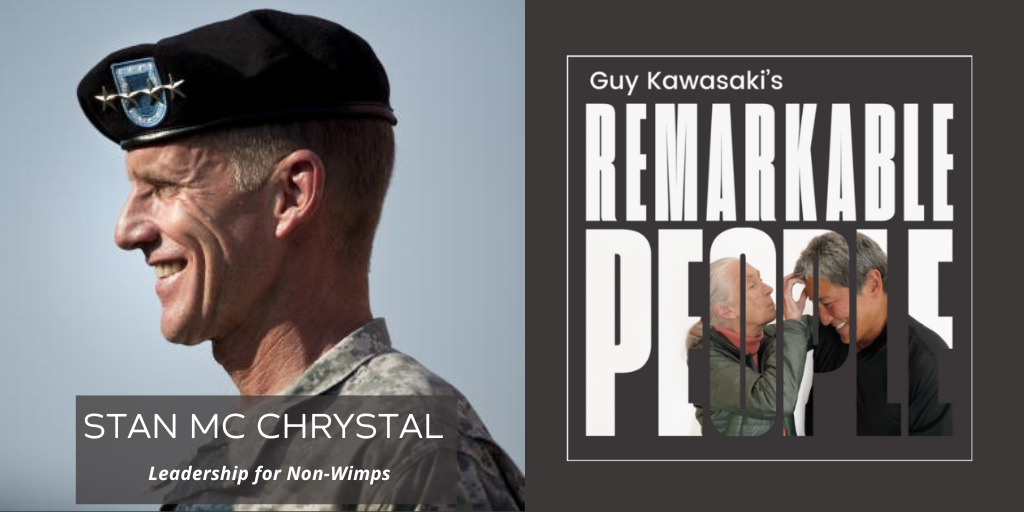

Helping me in this episode is the remarkable Stan McChrystal is a retired four-star US Army general who served in the Army for 34 years. He was the commander of the US and International Security Assistance Forces in Afghanistan. And he led the US’s premier military counter-terrorism force, the Joint Special Operations Command (JSOC).

He graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point and the Naval War College. Stan also accomplished fellowships at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and the Council on Foreign Relations.

In 2011, he founded the McChrystal Group, which includes an advisory team that improves the performance of organizations and mentors the men and women who lead them.

Stan is a senior fellow at Yale University’s Jackson Institute for Global Affairs. He sits on the boards of Navistar International Corporation, Siemens Government Technology, and JetBlue Airways.

His latest book is called Risk: A User’s Guide. It is the best book about leadership that I have ever read. At my expense, I’ve sent copies to the president of Sony Electronics, CEO of Liquid Death, Steve Case (founder of AOL), and Chip Wilson, founder of Lululemon.

The best part of this interview occurs in the final minute when he explains what I call the “granddaughter’s test” so be sure to listen to the very end.

This is Remarkable People. And now, here is the remarkable Stan McChrystal.

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Stan McChrystal

Guy Kawasaki:

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. We are on a mission to make you remarkable.

Helping me in this episode is the remarkable Stanley McChrystal.

He is a retired four star US Army general who served for thirty-four years.

He was the commander of the US and international security assistant forces in Afghanistan. He also led the US' premier military counterterrorism Force, the joint special operations command.

He graduated from the United States Military Academy at West Point and the Naval War College.

Stan also achieved fellowships at Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government and the Council of Foreign Relations.

In 2011, he founded the McChrystal Group. It is an advisory team that improves the performance of organizations and mentors the men and women who lead them. Stan is also a senior fellow at Yale University's Jackson Institute for Global Affairs.

He sits on the boards of Navistar International Corporation, Siemens Government Technology, and Jet Blue Airways.

His latest book is called Risk: A User's Guide. It is the best book about leadership that I have ever read.

At my expense, I sent copies to the president of Sony Electronics, the CEO of Liquid Death, Steve Case, founder of AOL, and Chip Wilson, founder of Lululemon.

In my humble opinion, the best part of this interview occurs in the last few minutes when Stan explains what I call the granddaughter's test.

Be sure to listen to the very end.

I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People. And now here is the remarkable Stanley McChrystal.

Your story about Nixon asking the Black person in Ghana after Ghana achieved independence, Nixon asking him, "How does it feel to be free?" And getting the answer, "I wouldn't know. I'm from Alabama." I had to laugh out loud. That's one of the best stories that I have ever heard or read in a book.

And the second thing I want to tell you is that I think this is the best book I have ever read about leadership. I don't know if you're a Peter Drucker fan, but I would rank your book right up there with Peter Drucker's, The Effective Executive.

Stanley McChrystal:

You're very kind. And just to give you a little bit more background on the Nixon story, my family's from Alabama, my mother's side of the family.

So when he describes that, it's got a very personal side to it. If you remember the old movie Mississippi Burning with Gene Hackman, about the killings down in Mississippi, it was filmed in our hometown, in Alabama.

So the little sense of you, understand that the reality what Alabama in 1957 was, and to a disturbing degree still is.

Guy Kawasaki:

I would be doing a service to managers all over the world if they read your book, because let's face it, most of these business books are bullshit. "Be open, be transparent, walk around the factory floor." Like, "Duh."

Stanley McChrystal:

It's funny because I hate business books. I've written two of them and I don't really read them. And I basically wrote this last one because there's so many scholarly books on risk and yet we always get it wrong.

And so my argument is if we're so good at risk, tell me why we screw it up so much. And that was the journey we were on.

Guy Kawasaki:

To copy one of the concepts that you used in your top ten tips, I did a brief pre-mortem of this interview. And I thought what could make it fail and what would failure be? And the most dangerous failure I think is you just get pissed off with me and hang up.

I just want to know if there's anything off limits. I know you ran the military action in Afghanistan so you can handle anything, but I don't want you hanging up on me.

So can I ask about Rolling Stone, resigning, Camp Nama, Pat Tillman? Or is anything off limits?

Stanley McChrystal:

Nothing's off limits, but you'll find that my answers on some of them may not be what you expect or what you want to hear.

Now, I will be candid. But yeah, anything is fair.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well hell, now I really want to ask about those.

Stanley McChrystal:

Let's start with Camp Nama because people get things and stories get a life of their own.

And that was chronologically the earliest. Camp Nama was a nickname, we never used it. That was given to a base that was next to Baghdad International Airport in Baghdad. And the special operations task force that I commanded had a base there. It was its main base in Iraq, although we had smaller teams out around the country, and then other teams out around the entire region.

Our mission was to go after Al Qaeda in Iraq. I took over in the fall of 2003. And you'll remember timeline-wise the invasion of Iraq that occurred in the early spring of 2003, late winter, early spring.

And initially the idea that we would overthrow the government of Saddam Hussein was going to be pretty straightforward.

There were some Americans who believed we'd drive in, overthrow that government, give the keys to a new government, and drive out. And of course that was completely unrealistic.

And within a few weeks it started to go very badly. First, there was this xenophobic response to foreigners classified as occupiers. Then there were the riots of a number of terrorist group that coalesced rejection against foreigners.

And by the fall of 2003, October, when I took command of the special ops task force, it had started to get pretty ugly. And it got ugly in two ways. Saddam Hussein was still on the loose. And his generals were out there. You might remember the old deck of cards. And our organization's mission was to try to capture those.

And then there was the rise of this new entity under a guy named Abu Musab al-Zarqawi. And that ultimately became known as Al Qaeda in Iraq. And we really couldn't put an absolute finger that he was in Iraq until later in 2003, right near the end of the year.

But we were starting to see the reflections of a more professional terrorist effort inside Iraq.

So you have first this cacophony of violence, a lot of it disorganized and whatnot.

And then inside that you have almost like a cancer growing of a more dangerous, foreign led, professional, and well-coordinated terrorist group.

But you got these two big problems I take over in October of 2003. And the force had been there since the invasion, so about six months. And the Camp Nama footprint by the airfield was to allow forces to go out by helicopter and sometimes vehicle to prosecute targets against HVTs, to capture kill high value targets, leaders of those.

Most important in the early weeks when I took over was going after Saddam Hussein, and we got him in December.

The Camp Nama allegations or stories came out about treatment of detainees. And the reality is when the United States went into the war on terror, we didn't have a framework of what we were going to do with detainees.

Think of previous wars. There were prisoners of war. And we saw this first in Afghanistan, when, "What do you do when you capture a bunch of Taliban and potentially some Al Qaeda fighters? How do you treat them? Are they prisoners of war, or are they something different, or are they terrorists?"

And so this started really a conundrum that the US still faces today, because they eventually came up with Guantanamo Bay, the idea of taking them there. There was this question of, "Do we try them as criminals? Do we treat them as prisoners of war? Release them when the war's over? How do we deal with this?"

And then there was this undercurrent that says, "We're in this new very difficult war on terror." And that takes a different kind of effectiveness. It takes intelligence gathering, much of which is based on interrogation of captured people. It requires things that, to be honest, although theoretically they were in US capabilities, we really didn't have that capability.

We didn't have trained interrogators in any numbers. We didn't have people with language skills for the region. We didn't have people with cultural acuity.

So I take over and one of the first things I do in October is I tour the command and I go into our detention facility right there at the Baghdad Airport, at that base.

And it's rudimentary to the extreme. It's a series of single cells that have been put together. And it has some practices that I thought were absolutely unacceptable. There were some dogs brought in there on occasion, they weren't allowed to chew anybody, but it was the idea that this would be an intimidation.

And I think there was one trained interrogator and a couple of interpreters who weren't trained interpreters for interrogation.

And so to put a description on it, it was a pretty amateurish effort. It wasn't intentionally evil. Nobody was torturing prisoners or anything like that. But we didn't have a frame of reference, or clear set of rules, or how we're going to deal with this.

So one of the first things I did when I took command is I told everybody, "Okay, we've got to clean this up. Because we can't have an operation run like this, because something bad's going to happen. We got to clean it up and we got to figure out what the right way to do this kind of operation is, because there's every likelihood we're going to do it for a long time."

And if you look historically at counter terrorist efforts, you have to have an effective way to take captured detainees, interrogate them, treat them the right way, keep them out of circulation, all the things that are necessary. And it takes a system to do that. And so we lack that entirely.

So the Camp Noma stories are, in my opinion, grossly overblown, but they're accurate to the point that the United States didn't know what it was doing. And it took us a long time to get our act together.

Again, I didn't see evil people trying to do the wrong thing, but I saw people with no background or experience trying to do something they'd never done before.

Guy Kawasaki:

How about Pat Tillman?

Stanley McChrystal:

Yeah, this one I get frustrated with, because I will tell you that from my perspective, the death of Pat Tillman is a tragedy. Good soldier, good ranger, good person. And in my mind, his death has been taken out of context and harmed a number of very good people in the process.

In the spring of 2004, there were a number of things going on. Iraq was literally melting down. There was the situation in Fallujah.

So Iraq had exploded into a higher level of violence. We also had forces in Afghanistan. And on an operation down in Southern Afghanistan, there was a firefight.

And I got a call, I was down in gutter at the moment when the call came in. I was visiting that the central command higher headquarters and I was told that we'd had killed in action. And I was told that it was Corporal Pat Tillman, a ranger.

I didn't know him, I had not met him, but I knew of him, because when he enlisted, that'd been a fairly high profile event.

But I said, "Okay." The next day I was scheduled to go to Afghanistan anyway, and I did that. So I got to Afghanistan and I met with the task force. And when I met with the task force, they were, of course, upset that they'd lost a ranger and they'd been in a firefight. And I sat down with the commander.

And several things happened. First is they were doing all the right things to deal with the loss of someone, going through the notification process, he's going through an investigation.

And the commander came to me and said, "Sir, there's something you need to know. We've looked at this thing and we think that there is a probability that this was a friendly fire incident, that he in fact was killed by another member."

Now, that's not unheard of in combat. It's certainly not something you want. Stonewall Jackson was killed in a friendly fire. Lesley J. McNair, during World War II, was killed in friendly fire.

So it happens more than you want, but it's one of those things that, obviously, you try to go to school on and make sure it doesn't happen again and get clarity. He said, "There's a good chance that he was killed in a friendly fire incident while he was maneuvering on what he thought was an enemy position."

And so he is maneuvering with what he thinks is an enemy position and he's moving heroically to do that. And another American force apparently trying to provide supporting fires struck him and kill him.

The reality was what Tillman did in the moment was courageous. He was doing the right thing. The fact that he's hit by friendly fire doesn't make any less courageous.

So one of the things they said is, "We want to recommend him for award for valor." And I said, "Given those things, do you feel that he earned it and that his actions in his mind met that?" And they said, "Yeah."

And so we went through, and I concurred with that assessment, and we passed that up. Simultaneously, I also wrote a message that went up my chain of command that said, "This is a high profile incident. You need to know that there is, in our estimation, and we're not sure yet, because the investigation's not complete. We believe there's a good likelihood that Corporal Tillman was killed by friendly fire."

And I wrote that message and I sent it up to chain of command.

Later much was made of the fact that message was classified. The reality was because of the nature of my command and my role, everything I sent was classified. I didn't have a way to send a non-classified.

So I sent it up the right chain of command. And I said, "I want you to know this because as people deal with the family and they deal with other things, it's important to have that context, that it's tragic we lost him, and he's a hero regardless, but it might have been friendly fire."

And so that went up the chain of command. Later, there were accusations of people burning his clothes. They did burn his uniform because it was covered with blood, and it was a sanitary thing, and it was just rangers doing the right thing. There were multiple investigations of what happened.

And I'm convinced it was friendly fire and it was a mistake.

But there became this idea that the military is doing a cover up. My response to that, I think there were six, and two years later, they're still coming to me and asking questions. They're saying, "You covered it up."

And I said, "No. I sent a message transmitting my assessment that it was likely the worst possible thing that it could be, friendly fire. That's not a coverup. When you send it up to the chain of command and you say, 'No, this is what we think happened.' How can that possibly be a cover up?"

And in notifying the family, which we were not involved in because we were the war fighting headquarters, there's an administrative headquarters, there were some issues in how they notified the family.

But the reality is a number of people grabbed pieces of this. They spun a narrative that doesn't match the facts. And they harmed the careers of some other military leaders that I know and they did it unfairly and wrong.

And there was a propagation of this idea of cover up and negative things that tarnished a lot of really well intentioned, courageous people. And I resent that. And it got political and whatnot.

So when these things happen and we don't really get and publicize ground truth, I think it's unfair to all the participants. And I don't think it does Corporal Tillman's memory any honor, either.

Guy Kawasaki:

And the last topic is Rolling Stone article. You or your staff criticizing VP Biden, and you get called back to Washington, and you resign or get fired.

Stanley McChrystal:

Here's what happened. The war in Afghanistan, I had been there for eight or nine months in command. In reality, the war wasn't very popular. It wasn't very popular in the United States at that point. It wasn't very popular in Europe. People had gotten tired of the war in Afghanistan.

And so one of the requirements to build the confidence of the Afghan people and the confidence of our force was to do media. You have got to have an information component to your campaign. I don't like doing that.

But as a consequence, I did an awful lot of interviews in media. The interview with the Rolling Stone article and he was a freelancer doing a project, was one of a whole bunch of them. And this particular individual had gotten approval to spend some time with us in Afghanistan.

And then later when we had to go to Europe to do the same thing, build support for the war in Paris and a couple other places. He wasn't with us a long time. The idea that he was an in embed is true. But he was an embed for two very short periods, two, three days, and if he'd go, and then at a time in Europe.

And he wrote an article and if you had been around the author, he was a very ingratiating guy. He just couldn't be more friendly, couldn't be better, but still we're adults. And you know that anybody coming to do an article is going to write the best article for them that they can.

And he had an opinion on the war in Afghanistan. And I think part of what he was trying to do was write an article that supported his opinion of the war.

Now, he wrote an article that came out. And anybody's free to read it.

And it depicts my command team as ill-discipline, locker room behavior. There are some dismissive comments about the vice president and some others. There's not direct, any single smoking gun, but it's a pretty unflattering picture.

I think it's unfair. I think it's an unfair picture. It's not the group I saw, but I've never contested it. And so that's his perspective and he can write that. And I've never taken that on.

When the article came out, to give a bit of context, this is after some months of some lack of trust between, we'll call it Department of Defense, and the military, and the new administration. Remember President Obama had taken over in January, and he had immediately been hit with a request from the military for additional forces for Afghanistan.

And he naturally was skeptical. He and his staff were skeptical. And so they went through a period where they negotiated over sending additional forces. They finally decided to send some.

And then I was asked to go take command in late May and actually deployed in June. And at that point there was a fair amount of concern, politically, in Washington over where Afghanistan is going. You'll remember that President Obama had campaigned against the war in Iraq, but he had described Afghanistan as the necessary war.

And so when he actually was elected, he is on record as saying that we actually have to take Afghanistan more seriously. And yet the situation Afghanistan, by the fall of 2008 was deteriorating really badly.

So he's got the war in Iraq, which seems to be going in a better direction, but Afghanistan is now deteriorating significantly and it's probably going to require some tough decisions. And so from day one in his presidency, he gets what I think no new president would ever want is something that looks, feels, and smells like Vietnam.

And he's asked to send additional troops, which looks, and feels, and smells like William Westmoreland asked for additional troops in Vietnam. And so I take over in June and I'm asked to do an assessment on what we have to do to accomplish our mission in Afghanistan.

And of course, the first problem was, "What's our mission?" And it was described to me as protect enough of Afghan's sovereignty that they can avoid being a sanctuary for Al Qaeda or other terrorist groups in the future. Which means they've got to be able to protect their own border.

They've got to be able to control actions in their country to the extent that they can prevent that dynamic from occurring. Which means you've got to do a pretty significant military ability, buildup of Afghan capability, development of governmental capacity, and provide foreign military support during that period. And so that's what I felt my mission was. That's what I described it back to the White House, and we went forward.

But the point is there's a certain amount of concern in DC and reexamination in the early fall of 2009 about, "What are we doing in Afghanistan?" Even though the President had said, "It's the essential war." There was a lot of people, Vice President Biden being the most notable, who really wanted us to re-look our level of effort in Afghanistan and act accordingly.

There was a decision making process and actions went forward. But that's all the background, to give you the sense that there was a level of distance, I'll call it, and in some cases mistrust on individual levels between the administration and the military.

Now, there's been this picture painted later about this cabal of generals who get together, and lock arms, and want more troops. If there was one, I never saw it. I certainly wasn't part of it, and I certainly think I would've been. Just didn't happen. That's just not true.

Instead, the military's trying to do what they think is right. Now, they see the problem from a different perspective than someone in DC might, but that causes the problem.

Then you get into the Rolling Stone article. So now, some months into all of this, six months into President Obama's new administration, buildup of a level of distrust. And he gets this Rolling Stone article that says, "You've got the runaway general and this group of people around him who are dismissive and whatnot, even disloyal would be one interpretation."

That's absolutely not my experience. I didn't see that, I didn't feel that. But again, an author gathers a perspective as he wants, he's got the right to do that.

My relationship with President Obama up to that was good. And when I was asked to fly back to the United States, I carried my resignation. And I went and met with President Obama, and it was very professional. And then, and since he's been a real gentleman to me.

And he simply asked me what had happened. And I said, "Well, I haven't had time to investigate it, but I will tell you that depiction doesn't reflect my team as I knew it. But here's the deal." And I had my resignation. And I said, "I brought my resignation, I'm prepared to resign.

And I have no hard feelings. If you want to accept that, that's great. Whatever's best for the mission. If you want me to go back and continue commanding, I'll do that, too. Whatever you think is best for US mission in Afghanistan." Because I thought I owed that to it.

And he was great about it. And he says, "I'm going to accept your resignation. But thanks for your service and whatnot."

So I walked out of there. And here's probably the important part of this, at least for me. I'd been in the army at that point as a commissioned officer for more than thirty-four years. My wife had been with me for all of those years.

She is a young military brat. We got married when I was still a second lieutenant. And I'd spent four years before that at West Point. And I actually was born in an Army hospital. My father was a soldier, my father's father was a soldier.

So all I'd ever identified with being was a soldier. And then, now thirty-eight years into me wearing uniform, I never once thought I'd be accused of disloyalty. I thought I could be fired for being incompetent. I thought there was a good chance I'd get killed with some of the stuff we'd done.

There's a whole bunch of things you prepare for in a military career, but you don't prepare for having the thing which is most sacred to you challenged, but you can't do anything about it.

And even worse, my father was a retired military, I think he's eighty-six at the time. And he watches this on the TV. My son is in college and he's watching this on the ticker of the news, disgraced General McChrystal.

And I leave the Oval Office, and I go across town to where my wife had been living while I was deployed. And I go into the entrance to the home. And she's standing there, because I'd just flown home the night before.

And I said, "It's over. Our lives as soldiers are over. He accepted my resignation." And she looked at me and she goes, "Good, we've always been happy and we'll always be happy."

And we made a decision in that moment, without shaking hands or hugging on it, we made a decision to live our life focusing forward. And what that meant was I wasn't going to spend any time readjudicating it. I wasn't going to go out, and write, and argue, and say, "I got screwed or whatever."

Because that's irrelevant.

What matters is the people who believed in me before, I wanted to conduct myself going forward so that what they saw for my conduct justified, "Yeah, I believed him and I was right to do that."

The people that had trusted me could look at me and say, "I trusted him and I was right to do that." And you can't spend a lot of time being bitter about things that you think may not have been fair, because the end of the day nobody cares.

The only people really care are you. And so it's been the best decision of my life, assisted by my wife, to focus forward. And so it's twelve years ago and in the twelve years literally, we've had this unbroken string of lucky events in our lives and this set of friends.

So I look at the Rolling Stone article, I wish it hadn't happened, but in many ways it unlocked things that would've never happened in my life if they hadn't.

Guy Kawasaki:

Huh, wow. Okay.

Stanley McChrystal:

You asked.

Guy Kawasaki:

So now that I know you won't hang up on me, I have to say that for many people listening to this, the military is a black box. We really don't know how it works.

And we get snippets of some retired marine general on CNN, et cetera. But can I ask you a series of questions about the military that might educate people so we understand this better?

Stanley McChrystal:

As long as upfront I can say, "Remember this is one guy's opinion and so everybody should discount it accordingly."

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, but what a guy.

Going into your book, tell me if I'm imagining this, but would you say that Putin is the modern day Edward Braddock?

Stanley McChrystal:

Wow, that's a hurtful comparison. He's much more at a strategic level, but there are some real commonalities. Edward Braddock had an arrogance of being a British regular officer with a frame of reference that led him to draw a number of conclusions that he would be able to march to Fort Duquesne and capture it.

But if you step back and look at it, he had to go hundreds of miles through absolute wilderness, relying on logistics that were in many cases provided by colonial contractors which weren't very reliable. And so there's a lot of truth to that. And what he tried to do was unrealistic from the outset with the assets he had.

And he was almost unwilling to think about the complexities that were going to cause him problems.

Guy Kawasaki:

And didn't you just describe Putin to some degree?

Stanley McChrystal:

That's exactly what Putin did.

I think he had this absolute belief that he needed to bring Ukraine back into the fold. And so I think Braddock didn't have an overarching gut thing like that. He just had an order. But then when Putin allowed the military to conduct a special operation that, when you step back six months, now, and look at it, was unrealistic from start to finish.

They just didn't have the level of competency, didn't have nearly enough forces, didn't have the other factors to give them a high probability of success.

Guy Kawasaki:

While we're on the subject, do you care to opine about who's going to win the Ukraine war and why?

Stanley McChrystal:

The answer is it depends. Where I think we are now is six months into it, Russia is certainly not going to get the kind of success that they would've wanted to get at the beginning.

They tried to begin the war with what we call a coup de main. And that means you take strategic points in the country, Kyiv being one, and you cause the government to collapse.

You caused as a Zelenskyy regime to go away. And I think he thought he could paralyze Ukraine and then change their behavior through a new government, whatnot. They weren't able to do that. Now they've had to be pushed back to the East, into the Donbas region in Crimea. Russia really has a very difficult time just mathematically now, trying to capture more of Ukraine.

Ukraine's a big place. It's angry, it's got a lot of people, and it's increasingly well-armed. So the idea that they will grind out a conquest is very unlikely.

On the other hand, the idea that Ukraine, if Russia decides not to give up, and they sink their teeth into the Donbas harder into Crimea, getting them out of there is going to be extraordinarily difficult as well.

And I won't say it's impossible, but it will take international effort much higher than we have done so far. And then the other option where Putin suddenly says, "Well, this was a big mistake, sorry. And we're pulling out." I just don't see a psychological pathway for him to do that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you think that the world is retreating from globalization to nationalism and that's going to create more of these situations?

Stanley McChrystal:

I do. I think that COVID helped it along, because what COVID did was it showed the vulnerability of supply chains all around the world. Not to politics in that particular case, but to other factors. And suddenly you find out that you are vulnerable economically to that.

So that's one impetus. But the other impetus is it's now been almost twenty or so years we've been seeing this move away from democracy towards more authoritarian leaders and the ability to control. I would not have predicted that in 1989 or 1990, 1991.

I felt were actually going in a direction where liberal democracies had momentum that were unlikely to stop. And I thought things like the internet and globalization would reinforce that, but it hasn't.

In fact, what we've found is things like social media, and information technology, and other things in many ways reinforce the ability of, instead of it shining light and transparency, what it's allowed to do is people to use disinformation and misinformation.

So I think we're in for a period, we'll call it a decade more of actually a rising level of authoritarian government and more hyper nationalistic governments. And of course historically when we see that, the chance of major wars goes up significantly because the players that are involved and the dynamics in those kinds of government, often, they benefit from wars of adventure and whatnot.

And so I think we enter an extraordinarily dangerous period for at least the next decade as this rises rather than has fallen.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you think that in the situation we're now in it's like we're in a war without getting our hands dirty. All we have to do is send over missiles and just get Congress to approve more expenditures, but we're not risking any lives.

Is that a fantasy kind of war? Is this not the ultimate beta test for all these new missiles, and radars, and all these things that now we could really see how it'll operate? To use the old breakfast analogy, are we just being the chicken and not the pig, making this breakfast?

Stanley McChrystal:

I'm going to answer in two ways. First, as a retired military guy and then is just an individual. As a retired military guy, you're exactly right.

This is like Spain in the late 1930s before the second World War, when the various players that later fought in the second World War, Soviet Union, Italy, Germany, all used it as a testing ground for equipment they developed, and tactics, and techniques, and whatnot.

So the answer is, we can do that. And to be honest, we should do that. Were in uniform now, I'd be advocating very strongly that we need to be pushing equipment there that we want to, as you say, beta test. We need to see how it works and what changes have got to be made.

Now, let me step just as a citizen, though. There is a danger whenever you think that you're in a war without risk. For example, in the 1980s, we supported the Mujahideen through Pakistan to fight the Soviet Union in Afghanistan for about a decade.

And the Afghans lost 1.2 million Afghans, fighting. We didn't lose people, but we just provided money. And it felt like a clean, nice win. We gave the Soviet Union their Vietnam. And we didn't get our hands dirty, as you said. I think we need to be careful with that because if you went to Russia right now, and you asked the average Russian, not just Vladimir Putin, but you ask the average Russian are they at war with the United States?

I think we'd be surprised what a large percentage would answer yes. I think that they believe, between sanctions and then the fact that we are very openly providing weapons that are killing Russian soldiers, they probably say, "Yes, we're absolutely at war with the United States."

Now, it doesn't matter that you and I think that the Russians were wrong and we've got a reason to do that. What matters is in the minds of those Russians who believe that they're at war with the United States, and it's a very small step for that to become a shooting war.

So I think that what the United States has got to do is first get very realistic about that. I personally believe we need to be robust in our support of Ukraine, but we need it to be open-eyed. and our western allies need to be open-eyed. This is not a risk free activity we're doing. It's not a freebie.

We don't get to just kill Russians through Ukrainians and get to watch from the sidelines. There's every likelihood that if it gets difficult enough for Vladimir Putin, he will take actions that raise the cost to us.

He's done some action with gas to Germany and whatnot, but he could employ tactical nuclear weapons and he could employ a number of other things that would increase the risk of our activities there.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let's say that Russia loses the war, but it has the humility to learn from the loss and the discipline to make corrections, therefore it becomes more dangerous.

So Russia losing the war could be bad and now we have the mother of all unintended consequences.

Stanley McChrystal:

Yeah, I think that's not impossible because if they lost the war, they would go to school on those things that tactically and logistically were a problem for them. Certainly, look at what they did in Chechnya. They went into Chechnya twice.

The first time they went in Chechnya, they were humiliated. The second time they went in, they flattened the city of Grozny. They learned. Now, they learned brutal lessons, but the reality is I think that's what they learned. I think we're seeing them learn on the battlefield right now. I think the Russians are getting smarter every day as both sides do.

But the reality is anytime someone fights for a while, they start to learn things. So, that's very possible.

Now, if you extrapolate beyond what happens on the battlefield, though, if we allow Russia to succeed in Ukraine, to keep a significant part of Ukraine, to make a somewhat believable argument that they were successful, they will also derive other lessons.

And the other lessons will be that this kind of activity is acceptable, it's within their reach. I think they're also starting to draw the conclusion that they can't let the Southern nations, the Central Asian states, they can't let them make any moves toward the West, or this will be viral.

And so I think Russia is saying right now, "We can't be weak at all. We can't give up our activity in Ukraine, or it will cause us to lose even more of what is," in their minds, "the Russian empire."

So everybody learns lessons from these things and in many cases I think those lessons could be very dangerous. The lesson we should be learning is unity is key. Unity in the West is essential, and as soon as we don't have it, I think we will pay a huge price for it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you think the future of warfare is more like a Russian state attack on solar winds or is it more like rolling tanks into Ukraine?

Stanley McChrystal:

Everybody's always trying to predict that. I think the one thing we need to understand about war is a thoughtful opponent will do what you are not good at. And so they will go to school on what you do.

So if, for example, the West builds a ton of tanks, and builds the Maginot line back up again, or equivalent things like that, then they won't fight that kind of war. They will fight a war of attacks on solar winds, and economic things, and information warfare, and weaken us that way.

If, however, we go too far the other way and we say, "There'll be no more artillery wars, there'll be no more tanks on the battlefield because we're now going to information, and cyber, and whatnot." They'll watch that too and they will punch where we are not.

So what does that mean? Do we have to be strong at everything and everywhere? And the answer is you can't do that. So you have to be good enough.

I personally think the future of war is going to be a smaller military component, but a very lethal part of it, like we're starting to see with these very accurate HIMARS missiles being used in Ukraine, unmanned aerial vehicles, things like that.

So it will be very lethal on the battlefield, and it will be very intel based. But really the war in Ukraine, if you want to go to school on it, this has been an information war, because if you think about it, before the invasion, go a year ago, most of us cared about Ukraine, but we didn't care very much.

And if Russia had invaded suddenly and succeeded, there are a lot of people who would've said, "We don't like that. It's too late to do anything, it's just the way it is. That's what Russia can do."

Instead, what happened was because there was this buildup and then a delay for the Olympics, I believe, and Russians massed on the border for too long before they went in, the Biden administration was able to put out intelligence and say, "Look, they're going to invade."

And so for a period of weeks they worked an information campaign against the Russians that said, "They're about to do something horrible." And they made that the world take notice. And then the most effective information war campaign I've ever seen has been waged by President Zelenskyy and his team.

And unless you are confused, we're the target. He is waging it on us, but we are actually happy about that. We've embraced Ukraine almost like the embattled defenders of the Alamo.

President Zelenskyy has been the perfect role model, heroic leader. Look how he dresses, look how he meets foreign leaders. Look at how he looks at the camera, and he says direct, brave things. He's emboldened us.

But he has won, so far, the information war because outside of Russia, almost everyone thinks that the Ukrainians are the good guys and the Russians are the bad guys. And so to get to your point of the future of war, I think that's going to be a huge component of every war.

It's always been part of it, but it will be more powerful than ever. And so I think that sides which leverage it thoughtfully and aggressively are going to be disproportionately successful.

Guy Kawasaki:

I've wondered why every day we see a drone showing HIMARS or something destroying Russian tanks and people.

How come we never see the Russian drone destroying the Ukrainians? Do the Russians not have video cameras?

Stanley McChrystal:

Our media has bought into it. We do see Russians destroying, but what do we see them destroying? Railroad stations, and killing civilians, markets. And so what Ukraine is putting out is, "Look at all these horrible things the Russians are doing with these high tech weapons, civilians."

And what you're seeing on the other side is, "Look at this US supplied weapon killing an evil Russian tank. Nobody likes a Russian tank, so it's okay to kill them. Forget that there's a crew inside that's died." And so it's part of that information warfare activity that's done really well.

Now, if you were in Russia, you'd be seeing something different. It's a different picture being painted.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let's say that you're secretary of defense of Taiwan and you're watching this.

Do you say to yourself, "Boy, tanks and aircraft carriers are no longer necessary. We just need a soldier with a hand carried missile or a mobile missile, HIMARS, and DJI drones."

So our tanks and aircraft carriers obsolete at this point or they still serve a purpose?

Stanley McChrystal:

They still serve a purpose and it will be for some time, because tanks on the ground in Taiwan and then aircraft carriers in Overwatch, they raise the cost of a Chinese assault on Taiwan. They make it very costly. Now, the other part of that, though is the United States and our allies must be able to reach into mainland China.

We must be able to reach in with missiles, and air, and information systems because you can't let China have a risk free assault of Taiwan. You can't let the only forces at risk be the ones that they actually use in the assault. You've got to keep mainland China at risk because again, that ratchets up the cost or the risk for them.

And so if you can keep that cost high enough, President Xi Jinping will always have to go, "Wow, I'm just not sure that this is worth it." If we ever let that cost slip low enough, then and suddenly it's a completely different calculation. And he has said that he is committed to bringing Taiwan back into the fold.

Guy Kawasaki:

But don't you think that so many political leaders have used the slippery slope theory to justify war, that, "If Vietnam goes, then Asia goes, and pretty soon Asia's all communist, and next thing you know the world's all communist and so we got to go to war, now."

Is this slippery slope really as slippery as political leaders would like to make it?

Stanley McChrystal:

Yeah, it's always in the eye of the beholder. And of course after the fact it looks different. Southeast Asia are now allies. And the time in Vietnam, you look back and say, "That was probably unnecessary."

Now, arguably it was not. You could make an argument that the effort in Korea and Vietnam both had an effect on the Soviet Union, and China, and whatnot. There's a counter argument.

But you're right, the slippery slope, the problem is how do you judge that if you allow, in 1938, if we looked at the Third Reich, Adolf Hitler is starting to make moves. We could have stopped him in '36 in the Rhineland, we could have stopped him in thirty eight, Czechoslovakia.

There was a series of times when it is believed that resolve against him would've stopped him in his tracks. And of course we didn't.

Now, you look at Ukraine and you say, "There's an argument that says, 'Well, Ukraine, some parts of its history, it's been part of Russia. Why don't we just let it be part of Russia? It's not worth it. Or Taiwan.'"

So hard to decide where that point is that you have to be strong. I personally think Ukraine is a place where the West needs to be strong now, particularly because of Vladimir Putin and the nature of that leader.

The question of Taiwan is a little murkier. And of course the argument they are trying to make is, "Hey, it's part of China, what are you worried about? Just let the natural thing happen."

And yet when we look at what happened to Hong Kong after promises were given one way, it's been a pretty different outcome. And Taiwan arguably has never actually been a part of mainland China like they depict. I think the best thing for China now would be to have America start to have the question of, "Is it really worth it? Maybe China's got a point."

And once they can get that discussion to a tipping point, then I think Western resolve to defend Taiwan will likely erode pretty quickly.

Guy Kawasaki:

And you as a military person, when you see Pelosi and other congressmen and women go to Taiwan, do you sit there, and scratch your head, and say, "Now, what the hell are they thinking? Why are they doing that?"

Or do you think that is affecting the Chinese perspective and saying, "Oh God, Nancy Pelosi likes Taiwan, we really better not invade."

Stanley McChrystal:

Well, my whole career I've been watching Congress people do things, and scratch my head, and ask them why they're doing that. Yeah, I can't judge that because I don't know all what was behind it.

I do think it requires thought when our elected officials below the national level, forget the president, vice president, whatnot, but elected officials, they go off and they start making foreign policy through their actions. And if it's not well coordinated, I think there's danger.

And I think that happens on both sides of the political aisle, but I worry about that a bit. I always liked the idea that partisan politics should stop at the shores of the United States, and what we do internationally should be pretty united around American policy.

That's never been the complete truth, but I would like to see us be better on that.

Guy Kawasaki:

This is the question that will just show my ignorance of how weapons work, but every day we read that the US, or Germany, or Poland, or somebody is sending this kind of airplane, or this kind of missile, or this kind of radar system.

And I just wonder, so you're telling me that a boat arrives at Ukraine, the HIMARS come off, and all the Ukrainian soldiers, they know how to fire the missile, maintain the missile, repair the missile? It's not like you shipped a Macintosh from the Apple Store, you open the box, and click, and go.

How does it work when, I don't know what a Ukraine first name is, he goes to the dock and there's a HIMARS missile system waiting for him. And you're like, "How does he know which button does what and all that stuff?"

Stanley McChrystal:

They do what they call new equipment training teams. And they send teams that, typically they'll pull people out from Ukraine and they'll train them in a very intensive period on how to operate that piece of equipment.

To my knowledge, we don't put American contractors or advisors on the ground. The Ukrainians are clever people. And when you're at war like this, you can learn these things pretty quickly.

Plus, in the days of connection and YouTube, how do you fix everything around your house? The way I do it is you go on YouTube.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm sure there's a TikTok video about how to repair a HIMARS.

I think I know the answer to this question, but in reality, what's harder, the war or the occupation?

Stanley McChrystal:

It's not making one be different from the other. Because the reality is the initial war, as most people would define it, going in and overwhelming the enemy's forces on the ground, getting to their capital, or whatever your objective, is hard, but it's not that hard. It's pretty straightforward.

The occupation of a country that doesn't want to be occupied is hellishly different, difficult because you need a vast number of forces. A country the size of Ukraine, if it was going to be occupied, would take several million soldiers to occupy it.

And in today's high tech world where every civilian or soldier can be pretty lethal, attacking the occupying forces, it's even harder than ever. So I think for Russia to occupy significant part of terrain where the people don't want them is really difficult.

Guy Kawasaki:

And so what you just said in hindsight, I think the acronym was COIN.

Do you think that was a flawed decision, or it ended too fast, or what happened there?

Stanley McChrystal:

Yeah, first off, it's really hard. I don't think it was a flawed decision because there's really not another option. If you've got an insurgency against a country, the only way to defeat that insurgency is to make the country's society and military strong enough withstand it.

Think of an analogy of the human body. If your body's weak, you get sick, and you're vulnerable. And so COIN, but it's hard because all the things about making the body of a nation healthy, particularly under pressure, is difficult.

And so there's just not another way, in my view, but we can't underestimate what it takes.

Guy Kawasaki:

You make the point like an old cartoon, that, "We have met the enemy and he is us." So why do you say that the greatest risk is usually internal?

Stanley McChrystal:

Because I think that most of the risks we face in retrospect, in the moment, that may be very daunting, but in retrospect we find that they're not ten feet tall and we can defeat them. We found with COVID-nineteen, we could develop vaccines with extraordinary speed.

We could produce them faster than ever, but then we couldn't get people to take them. It was extraordinary. And so if you look at any number of threats that come at our society, what we find is we don't communicate well between each other or we lack leadership.

We don't have a clear narrative of what it is we're trying to do. There are just so many things where we find out that it's our missteps or our inherent weaknesses that turn out to be lethal to us.

And this is where it comes back, in many cases, to some introspection and some leadership. Because if I want an organization to be less vulnerable to threats, the first thing people say is, "I got to go out, and I got to find the threats, and stomp on them or whatever."

You actually don't because that's impossible. You just can't know them. But what you can do is make the organization much more resilient, just more strong, just like a healthy person doesn't get sick, to any number of ranges of things, nearly as often as someone who is already compromised. And that's the whole idea. And I become deeply convinced of it.

Guy Kawasaki:

An extreme example, you would say that you can't go out and stomp Hurricane Katrina, but you can't prepare New Orleans for something like Katrina.

And that enemy is us not being prepared, not the hurricane.

Stanley McChrystal:

That's exactly right. And you can't even just do physical things, increase the levies, you can do some of that. But what you've got to do is prepare New Orleans for all kinds of things.

And it's got to be able to respond, it's got to be able to do rational actions in real time to unexpected threats.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, with that introduction, what exactly is good leadership?

Stanley McChrystal:

Good leadership, I've come to believe, is not that iconic Edward Braddock on his horse, leading this army through the woods. And he's very competent in many ways, British general. And I'm sure he was a courageous guy, ultimately killed in the fight.

But really, the good leader builds the organization. The good leader builds those capacities, starting with subordinate leaders, ensuring that there's clarity on what the organization is about. We'll call it narrative, but in many ways it's culture as well, ensuring that the organization has the habit and the willingness to adapt when necessary, ensuring that the organization can overcome inertia.

Because I don't know how many times you're in an organization and everybody can sit there and agree, "We ought to do this, but we won't do this because it's just too hard, whatever." And nothing happens.

And so the good leader actually is setting up those qualities in the organization that allow the organization to do that which only the organization can ultimately do. And sometimes it's a very humble kind of leadership. Sometimes it takes a little bit of head rapping to get people focused and in line.

But the reality is you're constantly building. And I would argue that in many cases in the moment of crisis, the leader is not important. They've either done their job beforehand or they haven't.

Guy Kawasaki:

And does this differ for military, versus private sector, versus political?

Stanley McChrystal:

Yeah, we pretend it does, but I think it's almost exactly the same. There are some different terms we use and we expect the military leader to act a certain way, but the basic requirements are identical.

Guy Kawasaki:

A lot of your discussion was about recognizing and reducing bias, and I want to know how we recognize and reduce bias.

Stanley McChrystal:

I think the first part is much more doable, recognizing bias, because reducing bias is something we all work on. But it's challenging because we just have it. If you've got it, in some cases you can step away from it.

Biases come up because of your background, because of your experience, because of your race, because of any number of things. You just are going to see the world a certain way. And then as we outline in the book, sometimes you're going to see it in the way that it's in your interest.

So for example, we talk about slavery in the pre-Civil War, American South. Slavery had been a point of argument for decades. And there had been all these philosophical books written on it, and arguments, and I'm reading a long book on the struggle inside the US Congress in the 1830s over it.

So people had a really clear idea of what the question was.

But if you step back, it was in the interest of a significant part of the South to have slavery. It was in their economic interest and then it was in their political interest to have it. And it was absolutely not in their interest to do away with it. So they are going to believe in it.

They almost have to believe in it, because cognitive dissonance says, "You won't do something that you think is wrong for very long. You'll change what you think." And as a consequence, you have a whole group of people who convince themselves that slavery was in the best interest of the nation and of the slaves themselves, the argument that they'd be in the jungle and they wouldn't be able to take care of themselves.

And so we step back now, 160 years later, and it looks ludicrous, but it's not ludicrous because take on some things in our own lives right now, there are certain things about the free market economy, about our ability to make choices where our children go to school, or any number of things that become pretty emotional.

And we feel very strongly about them, because it's in our interest to have that belief because that particular outcome supports us, whether it's, "We want low taxes because we got money and we don't want to pay a lot of taxes." It's pretty natural for people in that income bracket to think low taxes would be good.

And people in a very low tax, low income level, they have a different view because they benefit from the opposite. So as long as we start by understanding, we don't arrive at our opinions based upon deep thought and study, we get there. That's what it is.

Guy Kawasaki:

I would say that the flip side of bias is rationalization. And you have a great discussion about rationalizing in particular when you're taking the easy way.

So how do you know when you're rationalizing and taking the easy way? Or, if the easy way is actually the right thing to do?

Stanley McChrystal:

Wow, that is such a tough question. I think the first thing is, again, recognizing your bias. Recognize that you are going to be inclined to support the easy way because it's easier.

And so you are unlikely to give near as much weight to the other thing you should do simply because it's that way. And it takes an extraordinary person to be able to overcome that rationalization. I think this is where groups of people can do very well.

I think discussions, a dialectic on something like that where you start to bring in different views, it may not cause you to suddenly get up and go, "Yeah, we should take the hard way." But it will get people and groups into the position where they recognize, "There is another way, there is an argument for that other way we should consider that."

And sometimes just to be a member of the group, to show your willingness and the importance to you of being a member of the group, you make better decisions, you will go along with better decisions when it would be less inconvenient not to.

Guy Kawasaki:

This is, I think, where you'd say you should throw the tabletop, and the red team, and the pre-mortem at the problem.

Stanley McChrystal:

That's exactly right. Those things which are actions, which force you into thinking differently.

The red team kind of thing, which forces a different look at what you're doing, or the pre-mortem, or that sort of thing. Those are critical because they get you out of your comfort zone.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, So I'll leave you with one easy question.

Stanley McChrystal:

Yes sir.

Guy Kawasaki:

How does one develop moral courage?

Stanley McChrystal:

Wow. I think that one is extraordinarily important. I think introspection. You have got to set yourself some test for those decisions. The test that I use for my decisions is my granddaughters. I've got three granddaughters. They live next door to me. I'm very close to them.

And I want every decision I make when they see it, or they read about it later, after I'm gone, and they judge it, I want it to be one that I think that they will be proud of me. I think that if you have some forcing function to your moral courage, some kind of standard, that's the one I use.

There are other things that I've been taught. Some people use their religious background, whatever. But you have to have a framework because if you don't, you make every decision entirely independent of that. It's awful hard to get to the right answers.

Guy Kawasaki:

I hope you enjoyed this interview with General Stanley McChrystal. We learned about the future of war, the difficulty of occupying a country, how to control bias, and how to develop moral courage.

I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People.

Special thanks to Gautam Mukunda. Quite frankly, I don't think I would've ever gotten to Stanley McChrystal without his help.

My thanks to Jeff Sieh, Peg Fitzpatrick, Shannon Hernandez, Alexis Nishimura, Luis Magana, and the Drop in Queen of Santa Cruz, Madisun Nuismer.

We are the Remarkable People Team on a mission to make you remarkable. Mahalo and aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Leave a Reply