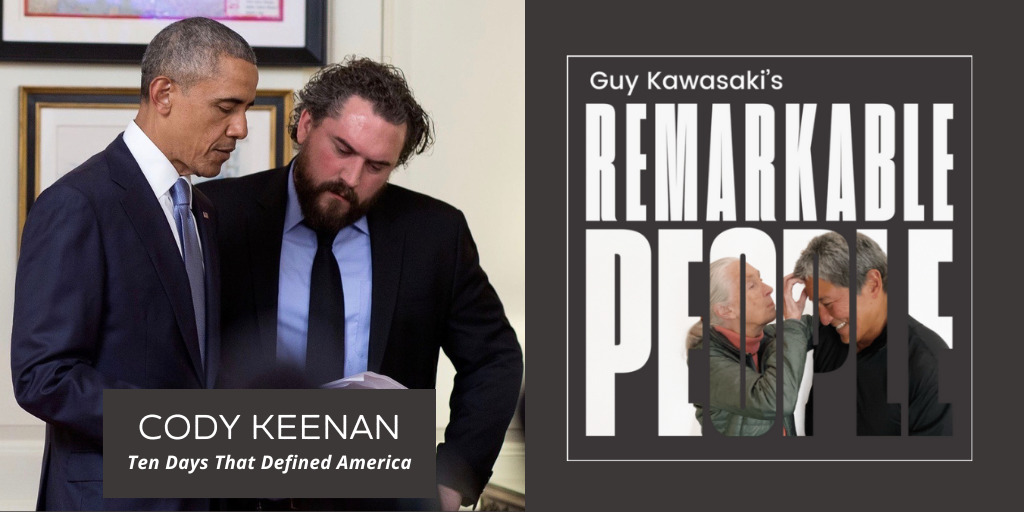

Today’s remarkable guest is the man Barack Obama called his Hemingway. His name is Cody Keenan, and this is his second appearance on Remarkable People. Cody was Barack Obama’s longtime collaborator and chief speech writer.

He started as an intern for Ted Kennedy, and after receiving his master’s degree, he worked in Barack Obama’s presidential campaign.

Cody obtained his master’s degree from Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government and his bachelor’s degree from Northwestern University.

He now teaches a course there on political speech writing.

In addition to teaching, he is also a partner in the speech writing firm Fenway Strategies.

He is also the father of a daughter. Her name is Grace, and she makes her first podcast appearance on this episode.

Not so coincidentally. Cody’s new book is called Grace.

The subtitle is; President Obama and Ten Days in the Battle for America.

Cody takes readers inside the Obama White House during the ten days following the mass shooting at the Emanuel AME Church in South Carolina in 2015.

This book is a remarkable narrative of the creation of Barack Obama’s eulogy and the preparation for the Supreme Court rulings on the Affordable Care Act and same-sex marriage.

@CodyKeenan takes us inside the craft of speechwriting at the highest level at the White House for President Barack Obama. Be the first to know 💡 #podcastaddict #speechwriting Share on XThis is Remarkable People. And now, here is the remarkable Cody Keenan.

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Cody Keenan

Guy Kawasaki:

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People. We are on a mission to make you remarkable.

Today's remarkable guest is the man Barack Obama called his Hemingway.

His name is Cody Keenan and this is his second appearance on Remarkable People.

Cody was Barack Obama's longtime collaborator and chief speech writer.

He started as an intern for Ted Kennedy and after receiving his master's degree, he worked in Barack Obama's presidential campaign.

Cody obtained his master's degree from Harvard University's John F. Kennedy's School of Government and his bachelor's degree from Northwestern University.

He now teaches a course there on political speech writing.

In addition to teaching, he is also a partner in the speech writing firm, Fenway Strategies.

He is also the father of a daughter. Her name is Grace, and she makes her first podcast appearance on this episode.

Not so coincidentally. Cody's new book is called Grace.

The subtitle is; President Obama and Ten Days in the Battle for America.

Cody takes readers inside the Obama White House during the ten days following the mass shooting at the Emanuel AME Church in South Carolina in 2015.

This book is a remarkable narrative of the creation of Barack Obama's eulogy and the preparation for the Supreme Court rulings on the Affordable Care Act and same sex marriage.

I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People. And now here is the remarkable, Cody Keenan.

When the book comes out and people ask, how is Grace doing? What are you going to say?

Cody Keenan:

Honestly, I'll probably say Gracie is doing great. She's two years old. She's hitting all her benchmarks and the book hopefully is also doing great.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay.

Cody Keenan:

But yeah, that's a tough one. It's confusing for people. I named them both at the same time, pretty much.

Guy Kawasaki:

You should have thought about that when you picked the title.

In the section where you talk about meeting your wife, I'm going to read you a quote. "They knew everything there was to know about Barack Obama. His past statements and positions, his voting record, his place of birth."

And then in parenthesis you have the word classified. So is that a joke or is that something you forgot to take out?

Well, it's classified. No, it's a joke. It's a joke about how everybody was always up in arms about whether or not he was born in America. He was, to make it clear, that was a joke.

Guy Kawasaki:

We're just going to fanboy for a couple more minutes.

So I want to tell you my most favorite line in the book, and the most favorite line in the book is, "When Obama gave instructions to retweet Romney's tweet about taking down the flag at Emanuel AME, while Obama dictates or approves the contents of his tweets, he didn't have the ability to tweet from his own phone."

Quote, quote, quote, quote. "Only morons would allow a president to do that." That was just fricking brilliant. If you don't anticipate-

Cody Keenan:

You can have some of the best lines in the book.

Guy Kawasaki:

I take it, you don't anticipate doing any signings at CPAC events, huh?

Cody Keenan:

Probably not. If they invite me, I'll go. I'll go anywhere to get this book out there in the world. But-

Guy Kawasaki:

Spoken like a true author.

Cody Keenan:

The president had the nuclear codes, but he did not have the Twitter password.

Guy Kawasaki:

Arguably his Twitter password might be more dangerous.

Much of the book is about anticipating the Affordable Care Act and same sex marriage, SCOTUS verdict.

And so just imagine what would your week have been like if this was when Roe versus Wade was coming up?

Cody Keenan:

Sorry, Guy, my daughter is right here at the door staring through and banging on it.

Hi, Gracie. I assume we can edit and I'll redo the question.

Guy Kawasaki:

We leave that in.

Cody Keenan:

All right. Great.

Guy Kawasaki:

This ain't NPR. This is Remarkable People.

Cody Keenan:

She's always got such a look of betrayal on her face like, "Who is that that you're paying attention to?"

Guy Kawasaki:

Someday when she's president, we're going to play this and say, "That was your first appearance on a podcast."

Cody Keenan:

Yeah. But to answer your question, it would've been completely different. And some of the people who received advanced copies of this book received them the week that the Roe decision came down, which changed the reading of it.

The events in the book, the shooting and the eulogy at the beginning and the end. But the two Supreme Court cases upholding Obamacare and finding a right to marriage equality in the constitution, those two cases weren't necessarily things that we made happen that week.

President Obama obviously fought for and won Obamacare, but it was also the result of a hundred years of advocacy for universal healthcare.

And marriage quality was the result of a fifty plus year movement for LGBTQ plus rights. And that's one of the things that inspired me to write the book, even though it takes place over ten days.

But in there, you see this kind of long sweep of American history and all these battles we've had for equality and justice.

And then the four years after the Obama presidency for me, what actually made the book really clear in my mind. It's not like at the end of the ten days in the White House, it was like, "Well, that was something. I'm going to write a book."

I didn't really think about it until after we left the White House and we were living through the mirror image, the dark mirror image of the Obama presidency. And that's kind of what inspired me to write about those ten days.

Guy Kawasaki:

What if you had to prepare for the Roe versus Wade decision? Would it have gone much the same or is that just so much heavier?

Cody Keenan:

Preparation would've gone the same because we made sure to prepare for every eventuality. We didn't know which way the Supreme Court was going to rule on in either of those cases. So we had three different speeches ready for the Obamacare decision.

We had three different speeches ready for the marriage equality decision. Should Roe have been that week, we would've had multiple speeches ready for that too. So we were always prepared for every eventuality.

It made life as a speech writer much more challenging of course, but it made the president's life easier, which is what we were going for.

And as you saw in the book, President Obama is not really superstitious, but he didn't look at the speech drafts in the event of failure. He didn't look at the draft for what would happen if Supreme Court struck down Obamacare or rejected the idea of a right to marriage quality.

He just didn't do it. He edited the winners because he was that confident. In fact, on the losing draft for the Obamacare decision. He wrote across the top, "Didn't need this one brother."

Guy Kawasaki:

So during that week of Roe versus Wade, there was a Cody Keenan sweating bullets in the White House?

Cody Keenan:

Yeah, for sure. His name is Vinay Reddy. He's just a great guy, kind soul, and a brilliant writer.

Guy Kawasaki:

Roughly a month after Emanuel AME in 2015, the Confederate flag came down in the South Carolina State House and then five years later Calhoun statue was removed.

So now it's 2022. What's your assessment of where we are today?

Cody Keenan:

Oh, boy. It's complicated just like America is. It's my first reaction to the Confederate flag coming down a month after the massacre and then the Calhoun statue and all these other statues is what took so long.

It takes forever for these things to happen. Change takes a long time. And that's kind of one of the, I think real flash points in our politics today is you've got these extremes and I'm not going to say extremes on both sides because I would equate them and they're not the same.

But you've got, I'm going to say, the far wing of the left wing of the Democratic Party who I agree with on most policy issues.

But there's this kind of growing sense that it's all or nothing right away. And the problem with that approach is you're usually more often than not going to end up with nothing.

You look at this, President Biden had a bunch of big legislative victories this summer, and of course there are things in the bill that aren't great, but 95 percent of it is great.

That's a pretty awesome trade-off in my mind. I think sometimes there's this sense that if I can't get 100 percent of what I want, then everyone is crooked and corrupt. It's just not the case.

Politics will never go 100 percent your way. It's certainly never got a hundred percent my way. And I think if that's your outlook, you're just going to be disappointed all the time.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you think we're at a tipping point where democracy dies or are we at a last gasp of white nationalism that cannot overcome demographic change?

Cody Keenan:

I don't know. I could be persuaded either way. There's no doubt that the majority of the country is more open to change, is more open to differences among people, a pro-truth, pro-democracy.

That segment of the country is only growing, but there are structural issues in democracy that actually makes it easier for that noisy minority to win, keep and maintain power. And you've seen a bunch of state legislatures right now. Republicans kind of rewriting the rules to lock in power.

So there is this kind of awful imbalance and it's one of the reasons why you get people who are so frustrated, but if there's more of us, why can't we do what we want?

I share that frustration. So not trying to filibuster, I just think it's more complicated.

I am hopeful that it's not a last gasp anytime soon, but maybe this is kind of the final generation of angry, violent and white nationalism, but you also see it growing among young people too.

So I don't think you can say that, but I'll end this answer on a more hopeful note, which is that one of the best things I do is teach and I teach seniors at Northwestern University.

And they're almost every single one of them to a fault is hopeful and idealistic and inpatient. And part of that impatience comes from lived experience.

I was born in 1980, so my first twenty years were ones of peace and prosperity.

In the late nineties, you'd think back to it was like we were just this colossus to stride the world and the biggest fights were over pop culture.

These students, my students, this year will have been born in 2000. So their entire lives have been book ended by 9/11 and wars, and two recessions, and a pandemic, and a climate that is getting worse fast and that might make the planet inhospitable in their lifetimes. And active shooter drills in their classrooms.

It's just a totally different life experience than what I had when I was their age and certainly what the too many old people in politics have lived.

So one way to heal this democracy is to stop being a gerontocracy and start electing more young people. And obviously the first step there is for more young people to run, but I think it's going to restore a lot of faith and democracy if people start seeing a congress and state legislatures and governor's expansions and White House filled with people who look like them and who've lived the same way that they have.

Guy Kawasaki:

Much of the book was you agonizing about the eulogy?

And my first question in that regard is when you hear a politician today using the phrase thoughts and prayers, what goes through your mind?

Cody Keenan:

It drives me nuts. What goes through my mind is usually anger at the sheer laziness and cynicism of it because... And I'll admit for the first two, three years of the Obama administration, we used that too before Newtown when our approach to mass shootings and kind of the country's noticing of mass shootings took a real turn.

You had twenty young children murdered in their school. That's when you realize thoughts and prayers don't do a whole lot.

They don't really accomplish anything. They are kind of the knee jerk response, especially now among Republicans who don't want to do anything.

So it drives me nuts. And President Obama, the biggest challenge in writing for him was that he took such great care with his speeches. He knew that a captive audience is a terrible thing to waste and he knew that every word you say matters. It can move armies or markets.

And with a eulogy in particular, he always wanted to do more than just pay tribute to the person we've lost. He wanted to reflect and inspire the rest of us as to what are our obligations now that that person is gone.

And some of his best speeches were eulogies because he had this moral imagination that when he tapped it, kind of amazing things could happen.

So as a speech writer, those were my biggest struggles, trying to get a speech draft to a point where he'd say, "Okay, I can work with this."

And in this book here, it's just kind of constantly simmering in the background. There's all these extraordinary events happen and you can really watch the country changing in real time.

Meanwhile, I'm trapped at my desk at three ‘o’clock in the morning trying to figure out what on earth to say in our umpteenth eulogy after a mass shooting. Unfortunately as he often did, the president took my draft and took it to a higher place.

Guy Kawasaki:

What goes through your mind when you hear a politician even today use the phrase thoughts and prayers after something like a mass shooting?

Cody Keenan:

It depends on the case, but usually disdain because thoughts and prayers aren't enough. They don't actually do anything anymore. Even if the person saying it is well intentioned.

But a lot of the time it's just like an octopus on the ocean floor will try to blind its predators by kicking up a bunch of sand. And that's what Republican politicians do after a mass shooting now.

Thoughts and prayers and let's find something to blame other than guns, which doesn't actually do anything about the real problem.

Guy Kawasaki:

How do politicians who come up with excuses talking about octopuses and sand, about “it was mental health or video games” or something like that.

And they just stand in the way of reasonable gun control that most Americans want. Why does that happen? What goes through their minds?

Cody Keenan:

The easiest explanation is what goes through their pockets and that's donations from the NRA. I think they're also afraid of their base.

And not everybody, not every single one of them, but 99 percent of them.

But in 2013, it was too conservative. Gun owners in the Senate, Joe Manchin and Pat Toomey who led the charge on background checks. Unfortunately 95 percent of Republicans voted no on it and that's why we didn't have universal background checks, which could have stopped something like Charleston from happening.

Republicans will always say once they're pass the blame game and the excuse making, they'll say, "Well, no law is going to stop every murder."

Well, of course not. No airbag or seatbelt saves every life in a car crash, but your job is to try to do as much good as you can. Imagine if it had just stopped one mass shooting and you'd have another three, four, ten people still with us.

So you never know until you try. It is constantly disheartening.

I'll say it was the one of the three times I ever saw President Obama angry and cynical was the day in April 2013 when the Senate voted down background checks.

Guy Kawasaki:

How does a person who has all the economic and educational advantages...like seriously, how do you become a Ted Cruz or a Lindsay Graham. What made you go down that path?

Cody Keenan:

You got me, man. I don't know. You'd have to ask them I guess.

I don't understand why people want to run for office if they don't want to make a positive difference in somebody's life. And then Ted Cruz has never seen a camera he doesn't love. I've never seen anyone less comfortable in his own skin than Ted Cruz.

One thing President Obama always tried to teach me is don't impugn motives to people. So even though I have plenty of thoughts about the Ted Cruz's and Lindsay Graham's of the world, and I include some of them in my book, what I can tell you is why I got into politics, which is I wanted to make sure that more people had the same chances that I did growing up.

I don't think I really realized that until I was probably in middle school, but I grew up on the north side of Chicago. You don't realize that just four or five miles away, you've got kids the same age living in despair in projects.

I learned about it in a book. Something that was just happening a few miles away from me and it had changed my life. There Are No Children Here by Alex Kotlowitz.

As you become more and more politically aware through teenage years in college years, I was like, I need to do something about this.

So I went into politics and went to work for people who were passionate about making a difference in people's lives, whether through better education, better healthcare, better economic opportunity, whatever we could do.

I just find so much reward in that. It's another thing about politics is you don't win every day. We were in the White House 2,922 days and you go home at the end of the day and just hope you moved the ball forward a little bit.

And then sometimes it pays off in just a thunderbolt like it did on these days in the book where the Supreme Court upheld Obamacare and found a right to marriage equality.

Nights when you passed Obamacare in the first place or got Bin Laden. It's years and years and years of effort for a big payoff that changes people's lives in ways they may never give you credit for.

And not just years, but decades. It's a way Barack Obama describes democracy, which is that it's just each generation's task to hand off the country to the next generation a little bit better than we found it.

I'm not necessarily trumpeting Barack Obama's victories here, but victories of a 100-year movement for universal healthcare.

Fifty-year movement for LGBTQ rights. And then you had this amazing movement grow out of the events of the book after a bunch of mass shootings where you got Moms Demand.

And I'm blanking on the name of the other one right now, of these kind of grassroots organizations that aren't making headway on the state level to pass new gun laws and then keep kids safe from gun violence.

It's an incredible thing to see. It just takes a long time and a lot of patience.

Guy Kawasaki:

When you were writing speeches, were you writing it for Barack Obama, for Democrats, for moderates, for yourself, for young people, history?

What was, this is where I want this speech to land kind of test?

Cody Keenan:

That's a good question. You're always trying to write a speech that only the speaker could give. Anything that Barack Obama said, it should be something that only he could say.

And you're always aware of your audiences. You're thinking of different audiences, but whatever goes on the printed page for the president to read that day has to be authentic and true to him.

So you don't pander. You don't say different things to different audiences. But I would be mindful of the audiences that would consume each speech.

Obviously, you've got the audience that's right there in front of you in the room, but when you're president in the United States, your audience can be anybody. Anywhere in the world at any time. Always assume you're on camera. Always assume somebody's recording, so you're never really off.

But there are a few times when I would think you don't really have the luxury to think about history a lot when you're doing as many speeches as we are.

We would sometimes do ten to fifteen a week, but when you get these big moments like when president would be going to speak at the fiftieth anniversary of the marches from Selma and Montgomery, you think about all the history that came before.

But on that speech for example, which I think was one of his best, we were thinking about the generation that comes after.

We were really writing that speech for young people sort of giving... And this was direction from President Obama, let's give today's young marchers and protestors their marching orders.

So in that sense, we were thinking about young people and even people reading the speech twenty, thirty, forty years from now.

But generally, your audience is everyone. So you want to be aware of that.

But always throwing a few pieces of red meat to whoever's in the room.

Guy Kawasaki:

There were places in the book that it seems like you had imposter syndrome. Was I good enough? Who am I to write the speech for Barack Obama?

First of all, is that true? And then how did you overcome that?

Cody Keenan:

That is absolutely true. I was lucky enough to start working in the White House when I was twenty-eight years old and I didn't feel worthy of it at the time.

I became chief speech writer for President Obama when I was thirty-two and I didn't feel worthy of it.

So I always had imposter syndrome.

I think most of us in the Obama White House did. And I actually think that's a good trade. It means you're constantly striving to do your best and make sure you're living up to the expectations people put on you and doing the job.

On the flip side, I don't think anybody in the Trump White House had imposter syndrome. I think every single one of them thought they deserved it and belonged there.

And you see how that worked out.

But I don't think any of us ever thought we deserved to be in the White House. Maybe there was some staff who had worked in previous administrations and knew their way around everything, but I was kind of constantly in awe of the surroundings, but also hyper aware of the responsibilities of the job that everything that comes out of our fingers as speech writers goes out into the world.

I never got over that. I had imposter syndrome until the day I walked out. I actually think it's a healthy thing because it meant I gave a damn.

And the added layer to that is when you're writing speeches for the first black president who's got an entire world of lived experience that's different than yours, there's an added burden there too especially when you're writing to black audiences.

So I'd always huddle with him and try to steal as much of his time as I could before one of those speeches to really get into his brain before I tried to go write something.

Guy Kawasaki:

Have you gotten over it?

Cody Keenan:

To an extent. And that's only because there's a really good chance that my career peaked five, six years ago and that was my one act. I still throw myself into any speech I write for somebody and I still approach each speech I write as the most important speech this person will ever give.

So there's always a little bit of fear and stress involved with each speech I write, but it's no longer crippling. These days the only thing that keeps me from sleeping soundly is our toddler.

Guy Kawasaki:

You alluded to this and I just want to return to this, which is this Obama tenet of don't assign motives to people. Do you have any more Obama or Keenan tenets for speeches?

Cody Keenan:

Oh, that's a good question. One of my tenets for speech that I always tell my team of speech writers is write each speech as if the audience has never heard the speaker before.

Because I would think about that a lot in the White House, especially when we traveled. He'd go to these, sometimes big... More often, not big cities, but also small towns where a president just doesn't come through often.

You'd see people of both sides of political divide come out because holy cow, there's a motorcade and a president and they'd come to the speech.

You see the looks on their faces. “I want to write every speech with a crowd like that in mind.”

So I'd tell my speech writers assume that this audience has never heard you before and write that way.

President Obama had a whole bunch of advice for it, but usually it's just right colloquially. Talk to people on the level. Voters are smarter than you think. People are smarter than we're told to expect.

So he always thought very highly of his audience and he wouldn't let us write down to anybody or try to write to lofty or high either which is just give me a fastball down the middle.

Guy Kawasaki:

You spend quite a bit talking about finding the muse. So have you codified that about listen to Miles Davis or Thelonious Monk and you get the Muse?

Cody Keenan:

No, the Muse was... I was always... My toddler is here. Hi, Grace.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh.

Cody Keenan:

Hi, Grace. Here she is.

Guy Kawasaki:

There's amazing Grace.

Cody Keenan:

You see the baby? That's you.

Guy Kawasaki:

I wish my camera were working. That's you.

Cody Keenan:

I promise, Guy is there on the other end.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wait, hang on. While you do that, I'm going to see if I can flip my camera.

Cody Keenan:

We're on a podcast. You're on a podcast. Can you say hi? Okay. Thanks Maria. That's okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

How do you get the Muse?

Cody Keenan:

Oh, yeah. The Muse was an Obama thing and there were just times he didn't want to be writing, which I understand.

So he'd typically say, and this was on a big speech, he'd say, Give me a draft and I'll see if the muse hits. I don't always know and made the muse hit for him. He'd say, "Read James Baldwin if you're stuck. Listen to Coltrane if you're not."

And I'd apply that to a bunch of different bands that I'd prefer to listen at times.

For him, I never always knew what struck him up there. And by up there, in the residence. He'd usually write late at night around one in the morning once everything was quiet and the world gets a little bigger at night.

It might be something he read with the Charleston eulogy. It was a letter he'd received from Marilynne Robinson, the author, that really struck something in him. When he was working on the Charleston eulogy, it was also the Supreme Court decisions kind of filled his heart a little bit.

And the real impetus on that speech was the families of the victims in Charleston all forgave the killer, which was extraordinary.

Not something I could bring myself to do if something had happened to my family, but they were his muse in a way. There were a lot of different forces conspiring over those ten days that ended up being Obama's muse and like I said, pushed that eulogy to a higher place.

Guy Kawasaki:

Another thing I found very interesting about the technique of speech writing from your book was the recommendation to find the silences. So could you explain that?

Cody Keenan:

Yeah, sure. The State of the Union address is, it's one of those speeches that every aspiring speech writer dreams of writing.

And then once you've written it once, you don't ever want to do it again. It's just this long bear of a speech where just a million different things are crammed in there.

And every year we'd sit down saying, "This is the year it's going to be different." And it just inertia keeps you from doing that. So 2015, early 2015, January just ruined my third consecutive Christmas by drafting a State of the Union address.

President Obama came back from Hawaii and I had sent him a draft and I was waiting to hear about his feedback. This is about eight days before the speech. I hadn't heard anything yet.

So I was starting to get equal parts nervous and annoyed. And then his assistant calls and asks me to come upstairs.

This is the Monday, eight days before the State of the Union address.

When the president wants to see you, it's not so he can just give you a gold star and tell you how great you are and send you on your way, he wants to talk.

So I go up there and the president was not in the Oval Office. So I give his assistant a very quizzical look and she said, "He's in the dining room and wants you to join him."

So you walk through the Oval Office and on the other side there's kind of the president's private work area. He's got a little study with a computer and he's got a bathroom and he's got a private dining room. He's in there eating lunch and he says, "Hey brother, sit down."

We start talking about our vacations, our Christmas vacations. He gets to go to Hawaii. I was trapped in DC trying to write a State of the Union address.

And he says, "So I read it and it's great. I think we're in the best shape we've been in this far out before his speech.”

And so instantly my whole body relaxes. And then he says, "There's only one thing. It's that everything in the speech is up here." He held his hand up above his head to show how tall somebody was. “And I need some of it down here.”

And then he'd lowered his hand at chest level. He said, “I need some high points and I need some quiet moments. And the speech is just…everything is in here.”

And I said, "Well, yeah, that's the thing about these State of the Union address is like everything is in here. It's a mess."

He said, "No, let me try to explain this differently. You listen to Miles Davis." And I said, "I do not." He said, What they say about Miles Davis, obviously, I did not." He says, "It's the notes you don't play. It's the silences that really made Miles Davis."

And so I start following what he's saying. And so you're right. In a speech, you do need quiet moments. You do need emotional highs and lows. You do need laughter and poignancy and all these different things.

And that sort of flew out of my brain while I was putting together his State of the Union address.

So he said, "Look, I don't want you to work tonight. I want you to go home. I want you to pour a drink and listen to Miles Davis. And then tomorrow I want you to come back to work and find me some silences."

I thought it was really cool advice, but I tried to think about that with every speech going forward. And even to an extent in life, try to find some silences when you can. I say this as my baby is squealing in the background, but try to find the silences.

We're all busy. We do too much.

For example, here, I'm no wellness guru obviously, but at 6 ‘o’ clock every day, I'm with my daughter until bedtime.

I don't look at my phone and I don't answer emails. It's just her. As noisy as she is, that's one of my silences. This is just playing with her and spending time with her.

Guy Kawasaki:

When I had my first child who is now thirty, people told me, "Guy, you have to cherish these years because you're going to wake up one day and he's going to be in college."

And I said, "There's no way. That's eighteen years from now. That's forever."

They were right. You're holding her on your lap now and pretty soon it's going to be junior prom and you're going to be worried about the guy or girl that she's dating.

I didn't listen to anybody when they told me that. I don't expect you to listen to me, but it's true.

Cody Keenan:

No, she's grown up so fast. Well, one of the amazing things about the pandemic for all of its horrors and pain is that I've gotten to spend twenty-four hours a day with my daughter since she was born.

My wife and I are lucky enough to be able to work from our apartment. It gets pretty crowded in here, but unlike me, both my parents worked twelve hour days when I was this age.

But our daughter only knows a world where we're both around all the time. And it's pretty amazing. And we feel very fortunate to be able to do that.

Guy Kawasaki:

I've had a series of scientists and doctors on this podcast, and every one of them says that learning begins from the moment you come out of the womb.

And that baby of yours should hear conversation and interaction from the moment she's born. Don't think education starts in preschool.

I have one more big question for you, and then I have one more morbid question that you might not want to answer.

Cody Keenan:

All right.

Guy Kawasaki:

So the big question is, with all this exposure to Barack Obama in very interesting times, to put it mildly, how does one learn to be graceful?

Cody Keenan:

That's a great question, Guy. It's a great question that no one's asked me before. I don't know.

I think I'm constantly striving for it. If there's one thing I'm very self-aware about, it's how short I fall of who I want to be in the life I want to live.

And I probably dwell on that too much. My wife says I'm too hard on myself, but I'm always thinking that I need to be a better friend, a better listener, a better father, a better husband.

And Grace as difficult as that question does that seem, it's actually probably pretty easy if we just think about it.

What makes it hard is that we've got this media environment and political environment that sort of trains us to be at each other's throats to be all or nothing.

Everything is either all good or all bad. Everybody is good or evil.

There is no nuance there. No shades of gray. There are not different sides to an argument. Compromise is not okay.

And people are much more nuanced than that. People are more difficult than that. We have no idea what the person in the department next to us is going through, what the person on the street is going through.

So we shouldn't assume that we know. We shouldn't instantly treat people like they've wronged us. Maybe they're just having a bad day.

I'm just coming up with all of this on the fly, but there are infinite ways to be graceful. This where Grace came from in the eulogy and for the book title is three days, two days after this racist mass shooting, a guy goes in there who's got a Confederate flag patch on his backpack who'd been self-radicalized on the internet as a white supremacist, white nationalist and slaughters nine black Americans.

Two days after that, the family members of these victims are on live national television in open court.

One by one they forgive the killer. It was just astonishing. It's grace and forgiveness or tenets of the AME Church, the church that all these people belong to.

I get it conceptually. I just don't think I could do that. I think I'd be vindictive, I would want Old Testament justice.

But they do this and it just changes the whole tone tenor of the week. I can't prove it, but the debate over the Confederate flag and guns seemed a little bit more grown up than usual.

Maybe Confederate flag defenders were just hiding because the massacre was carried out under their banner. I don't know.

But then the flag starts coming down over State House in the south. Less than a week after shooting, the Republican governor of Alabama ordered it brought down.

You've got companies bringing it down off the shelves. So we're seeing all this happening while we're arguing inside the White House about whether or not to give a eulogy at all, because the president had said after background checks failed in the Senate, that he didn't want to do this after mass shooting anymore because he didn't want to normalize it.

He didn't want this to be normal. And his words, in his words, clearly weren't helping.

But we see all this and he's inspired. And he said, "Look, if we go give a eulogy there, this is what I want to talk about, what those families did. I want to talk about the concept of grace."

Now, that's a big example for giving someone that murdered your father, mother, child, sister. My God, you can't do that. But those little things, yeah, we probably can do.

And we ended up naming our daughter Grace. It wasn't planned, but my wife found out she was pregnant two weeks before... We had just moved to New York City and she found out two weeks before everything shut down for the pandemic.

So we spent those first months of pregnancy alone, kind of nervous and worried, especially in New York City. You had 30,000 people dying and you're worried that if you touch an elevator button, you're going to get it.

So we just hunkered down to protect the baby and gradually emerge. And then over the summer, you've got protests every day for over a month in our neighborhood, back and forth over George Floyd and social justice and racial justice.

We finally masked up, went out and joined them. And then you had this kind of long, drawn out presidential election. It was a big stressful year.

But Gracie, our daughter, was a relatively easy pregnancy. No pregnancy is easy, but she was this constant reassuring presence who kicked at the same time every night just to let us know she was there.

And the labor was quick. It took us a day. We didn't name her until the second day, but we just looked at each other and we were like, her name is Grace, because just, we didn't deserve it, but she gave it to us anyway.

Guy Kawasaki:

Can I call Kristen up and ask her if she remembers it as quick and easy too?

Cody Keenan:

I hope I said relatively. Like I said, there is nothing easy about pregnancy. Labor was not easy. Labor was twenty-six hours. Delivery was forty minutes.

But Gracie... And she has been a really relatively easy baby. She's lived up to the name at times. Maybe not during this podcast, but you know.

Guy Kawasaki:

I know you're a Cubs fan. But to use a basketball analogy, parenting doesn't really get interesting until you have to go from man to man to zone. Right now you're two on one. Pretty soon you can be two on two. When it's three on two and four on two, that's when it gets interesting.

Cody Keenan:

All of your advice on parenting seems to be, it gets worse.

Guy Kawasaki:

No. I have two kids biologically and we've adopted two kids, and nothing has brought me greater joy than my four kids. Nothing in the world.

Cody Keenan:

That's great.

Guy Kawasaki:

With total certainty.

Cody Keenan:

Yeah, we joke that-

Guy Kawasaki:

So I decided that my morbid question would be in poor taste, so I'm not going to ask it.

Cody Keenan:

All right. Ask me after the show.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. No, I'll ask it now and then we can cut it because you might think it's a good question or you might think it's morbid and tasteless.

So the question is, would you rather have Barack or Michelle give your eulogy?

Cody Keenan:

Oh. No, I don't think that's morbid at all. It's actually an easy answer.

It's Barack only because he knows me better. He and I shared a lot of stress and frustration, and triumph, and heartbreak.

We've been with each other at some of our highest and lowest moments. He wouldn't be my first choice out of all my friends to do it, but between he and the First Lady, I'd choose him.

Now, that is not to dismiss the First Lady's talent.

On game day, she shines. That's what we call the day when you give a big speech. As I wrote the book, she has this thing about her where she just rides the razor's edge of tears when she's giving a big speech.

It's silent. People are silent when they watch her speak before they erupt into wild applause. But she would make more people cry than he would.

But I think he'd give a better speech only because he knows me better.

Guy Kawasaki:

One last thing, why don't you explain to the audience why they should buy this book? I have to tell you, I love that.

So somebody's out there listening and this is your chance to convince them to buy the book.

Cody Keenan:

Yeah. Well first of all, thanks for saying that, Guy. I appreciate it. But first of all, it's just a good story.

This happened. This was this remarkable ten-day period in American history that I wanted to write down. I wanted to be first to write down, I wanted to live and I want my daughter to know about it.

I want people to read about it. I tried to tell it as a good story. I kept to those ten days. It's tight.

It is 28 percent as long as President Obama's.

So you can read it and in just a few sittings.

But it's also going to make you believe again, beyond just the narrative of those ten days. You can see kind of all these forces in our country conspiring for good or for ill.

And everyone is striving to answer the question, who are we? What does it mean to be an American? What does America mean? What are our rights and responsibilities to each other and which side in the clash of wills is going to win out?

And that's still an open question. But my hope is after reading this book, people will feel inspired again about the great things we can achieve together as a country.

Guy Kawasaki:

If there can be several seasons with Kiefer Sutherland, just on twenty-four hours. I'm sure they could make a movie out this.

It must say something about both of us that you would interview with me again and I would want you back on the show that. In the history of the Remarkable People podcast, it's only been Jane Goodall, Robert Cialdini and Cody Keenan that's been on twice.

Cody Keenan:

That's amazing, man.

Guy Kawasaki:

So you're in good company. I hope you consider it that way.

Cody Keenan:

I'm very humbled and honored by it. It's great to be back with you. And you make it so easy.

Guy Kawasaki:

All righty. Thank you so much. Sorry about my hearing. Sorry about the technology, but-

Cody Keenan:

Thanks so much.

Guy Kawasaki:

... now the editing begins.

Cody Keenan:

Sorry about the baby. It's her first podcast though.

So if I'm one of the first to be on your show twice, you can now say you had Grace Keenan on your podcast. This is her first pod.

Guy Kawasaki:

So there you have it.

The inside narrative on ten days that helped make America.

Who among us would have such grace as those people who lost loved ones in the mass shooting?

I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People. My thanks to Peg Fitzpatrick, Jeff Sieh, Madisun Nuismer, Shannon Hernandez, Luis Magana, and Alexis Nishimura.

Until next time, Mahalo and aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Leave a Reply