This episode’s guest is Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston. She is the author of Farewell to Manzanar.

This book was written in the 1970s when Jeanne was thirty-seven. It chronicles her family’s internment during World War II. It is one of the books that many American schools use to help students understand racism and prejudice.

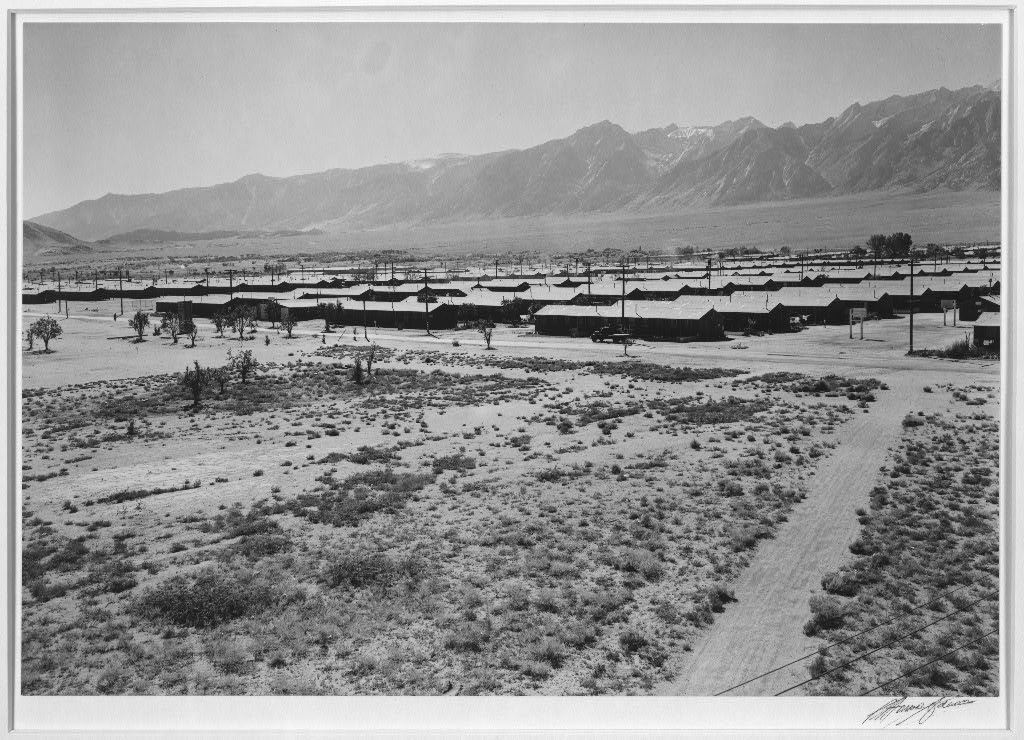

Jeanne was seven when her family was uprooted from Long Beach and placed in the Manzanar internment camp in the High Sierra of California. In total, 120,000 Japanese suffered from the same treatment. It was done in the name of security. The fear was the Japanese and Japanese-Americans in America would sabotage America’s war efforts.

In this interview, she explains what happened to her and her family and her hindsights about the experience as well as how it relates to the racist environment in America today. However, don’t expect anger and bitterness–because she has come to terms with what happened.

In fact, she has traveled throughout America in order to educate people so something like this doesn’t happen again.

To fully understand her interview, here are some definitions and explanations:

- Shikata ga nai is the Japanese concept that something “cannot be helped” or “nothing can be done.” It’s not necessarily defeatest or angry–it’s more like “it is what it is, so stop feeling sorry for yourself and suck it up.”

- Issei refers to the first generation of Japanese to emigrate to America. Nissei is the second generation of Japanese-Americans. They were born in America, and she is one.

- Kibei describes Japanese Americans, that is people born in America, who returned to Japan for their education, and then came back to America.

- The 442 Regimental Combat Team was a part of the US Army. It was made up of primarily sansei Japanese Americans from Hawaii. The 442nd first fought in Europe during World War II. For its size and length of service, it is the most decorated unit in American military history. Much of the motivation of the members of the 442nd was to demonstrate their loyalty to America even when Japanese Americans were being interned.

- The JACL is the Japanese American Citizens League. It is the civil-rights organization whose purpose is to foster the progress of Japanese Americans and Asian Americans to fight bigotry and prejudice.

- Katonk is a term used in Hawaii and by people from Hawaii to refer to Japanese Americans born on the mainland. The interview discusses the difference in perspective between katonks and Japanese Americans from Hawaii–such as me. It’s not a completely negative term, but it’s certainly not positive.

I hope you enjoy Jeanne’s wisdom. The goal of this episode is to help prevent anything like this from happening again.

Question of the week!

This week’s question is:

Can you imagine having all your rights stripped away in America? It's happened before. #remarkablepeople Share on X

Use the #remarkablepeople hashtag to join the conversation!

Where to subscribe: Apple Podcast | Google Podcasts

Learn from Remarkable People Guest, Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston

- Book, Farewell to Manzanar

Follow Remarkable People Host, Guy Kawasaki

I’m Guy Kawasaki, and this Remarkable People. My thanks to Jeff Sieh and Peg Fitzpatrick for their awesome work in helping me deliver this podcast every week.

Guy Kawasaki: I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. This episode's guest is Jeanne Wakatsuki. She's the author of Farewell to Manzanar. This book was written in the 1970’s, when Jean was thirty-seven. It chronicles her family's internment during World War II. It is one of the books that many American schools use to help students understand racism and prejudice.

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

Jeanne was seven when her family was uprooted from Long Beach and placed in the Manzanar internment camp in the High Sierra of California. In total 120,000 Japanese suffered from the same treatment. It was done in the name of security. The fear was that Japanese would sabotage America's war efforts.

In this interview, she explains what happened to her and her family, and her hindsights about the experience, as well as how it relates to the racist environment in America today. However, don't expect anger and bitterness, because she has come to terms with what happened. In fact, she has traveled throughout America in order to educate people, so something like this doesn't happen again. To fully understand her interview, here are some definitions and explanations.

Shikata ga nai is a Japanese concept that something cannot be helped, or nothing can be done. It's not necessarily defeatist or angry. It's more like, "It is what it is, so stop feeling sorry for yourself and deal with it." Issei refers to the first generation of Japanese to immigrate to America. Nisei is the second generation of Japanese Americans. They were born in America, and she is one. Sansei, FYI, is the third generation of Japanese Americans. I am a Sansei. Kibei describes Japanese Americans, that is people born in America, who returned to Japan for their education, and then came back to America.

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team was part of the US Army. It was made up of primarily Sansei Japanese Americans from Hawaii. The 442nd first fought in Europe during World War II. For its size and length of service, it is the most decorated unit in American military history. Much of the motivation of the members of the 442 was to demonstrate their loyalty to America, even when Japanese Americans were being interned.

The JACL is the Japanese American Citizens League. It is a civil rights organization whose purpose is to foster the progress of Japanese Americans and Asian-Americans, to fight bigotry and prejudice. Katonk is a term used in Hawaii, and by people from Hawaii, to refer to Japanese Americans born on the mainland. This interview discusses the difference in perspective between katonks, and Japanese Americans from Hawaii, such as me. It is not completely a negative term, but it's certainly not positive.

In the second half of this interview, Jeanne discussed the time she almost went on Glenn Beck's show. The voice you will hear in the background is Gabby Houston, her daughter. She was sitting in on the interview, and she chimed in to help explain the story. The goal of this episode is to prevent anything like this from happening again. I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. And now, here's Jeanne Wakatsuki.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: My father, of course, as soon as the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the FBI were over the house because he was a fisherman. He was also Issei, meaning that he was born in Japan. He also studied, and he was an educated man, so the FBI came, and he was gone. I was a child then, so I couldn't recall exactly what was going on, but I do know the results in the family, which was great fear, because the head of the family, and my father is a very powerful man, he's a real Issei type, very powerful, was gone.

And then of course, all the rumblings of the war, and the racism that came out of that, and the whole thing about the internment. This was unprecedented, to get a whole group of people. But that was way out in the plains someplace, but in Los Angeles, or in cities in Hawaii, they say, "Okay. This group of people, Japanese, report to a certain church at a certain part of Los Angeles. Bring only that which you can carry, and we'll see you there." I mean, it wasn't that flippant, but of course that's what happened. So people met at the certain place, left their cars, left their homes. What could they do? If they were making payments to the banks, which of course, most of the people were, you can't make the payments anymore so that's how they lost their home.

Guy Kawasaki: The boats.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh yeah. Oh the boat. The FBI came in. They just confiscated that immediately.

Guy Kawasaki: And the FBI thought that your father was taking fuel to submarines off the coast?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: That's what they accused him of doing.

Guy Kawasaki: Because he had barrels on the deck?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yeah. Of chum. There was not only ignorance, but there was tremendous prejudice, and so they wouldn't even... They didn't even know what chum was probably.

Guy Kawasaki: So your father's taken away.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yes. Disappeared. I don't know exactly how the official word got around, that where you were to go, but I think in the Japanese community, they said, "Oh yeah, they're going to pick up a whole group of people at the church in Los Angeles, so meet there. Everybody from Boyle Heights, meet there." And that's how the people were, I think...

Guy Kawasaki: So you voluntarily went there?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh yes. What could we do? There were no men. They picked up the Issei who were thirties and forty years old. My oldest brother was late teens right, or early twenty. And already, they had experience, they knew their “place in the society,” because at that time, the twenties and thirties, and before that, there was tremendous anti-Asian feeling on the West Coast.

We went straight to Manzanar, but other people were in this, I guess it would be this area, taken to the Tanforan Racetrack, and they lived in the stalls there. They put them in there because that was confined. And they did that at the Santa Anita Racetrack. So that was picking up the people, taking them there, and then from there, they were dispersed to these concentration camps, of which there were...was it 10? In the most remote parts of the country: Arkansas, Arizona, away from the west coast.

Guy Kawasaki: So now you get to the camp, and what is it like?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: I would compare it to, gosh, closest to would be like the reservations that they put the Indians in, except of course we couldn't leave. It was barbed wire. Manzanar was a mile square and had thirty-six blocks. Within each block you had twelve barracks, and in the barracks, there were either three or four apartments in the barracks, and one family lived in each of those apartments. So it was like we were in the army. They had barracks. We lived in the barracks. Because they just threw the barracks together, and so one of the, I think, of the people who were there, the young boys or the young men, they would get like a big can, and then you take off the top. But they get that top and they would cover the holes, and that's how they would cover the holes that were in the floors. They were kind of ingenious. And then it was so cold, it was so bad for that first year, six months, that they then came with linoleum and covered the floors. It was too cold.

Guy Kawasaki: At that point, were people just accepting that they can't do anything? What was the attitude? What was the morale like? I know there was a riot, so at some point...

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yes, but remember they had all... Basically they took the leaders of the camp, especially the Issei, which was like my father. So my father was being in his forties, right? So that's what they did. They just snipped the chiefs, the leaders, and so that the young Nisei men had to take over and assume leadership in this community, and then were put into this strange community of barracks, like army, except their family's living there.

And then of course they chose camp leaders, and you never saw white people in the camp. Unless, after a year, when they put in a school, then they had white teachers that came. But the white people would be just soldiers who were guarding outside, and later on, teachers would come in. So basically when you come in there...

I never saw Japanese when I was living in Ocean Park. So suddenly I was in this community, everybody was Japanese, and some of them couldn't speak English, like Terminal Island. I was in this really strange place, because I couldn't understand what they were saying. So it was just the most insane thing that happened. There was such ignorance about who Japanese were, and about dealing with any other racial group.

Guy Kawasaki: What was the relationship with, for example, the guards?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh, well, there's no white people in the camp. After the second year, we did have a school, then a lot of Quakers and high-minded white people came to teach in the schools, but the first year it was crazy. That's when they had the big riots and everything. I never saw any white people in the first months, in the first year, except soldiers. Of course we were in barbed wire, so there were four, I don't know how many towers there were, and those were soldiers with machine guns up there in case any of us tried to leave. Who's going to go out in that snake infested desert?

Guy Kawasaki: Eventually, it became sort of a functioning entity, right? Like a city?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh absolutely.

Guy Kawasaki: With a school...

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Absolutely. Gardens. I'm talking about Manzanar. I don't know how other camps worked, because I'm sure in Arizona it would be different, because the weather would be so different, and Arkansas. We ate better than the people outside, because we raised our own food, pig farms. And that's all they had to do, was run the camp.

Guy Kawasaki: You mentioned the concept of Shikata ga nai several times. With hindsight, do you think Shikata ga nai was the right attitude?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: I think it was the only one where they could survive because there's no way we could have rebelled with guns. We would all been killed, right? So how do you deal with this, and make the, quote, best of it? In other words, instead of going into deep depression or remorse and so forth.

So I think what they did was just, because they had leadership with these different men or women and getting together, and then they started making farms, growing farms, and raising chickens, and so forth. And then you have poor white people, and they would see that the Japanese were growing vegetables, and dairy farm, or whatever it was. And these poor people, who didn't have the wherewithal, and the farming skills, and so forth. So the Japanese were starting to feed the poor whites. That's a fact.

Guy Kawasaki: Wow. I'm from Hawaii, and when I came to Stanford, for my undergraduate education, I met Japanese Americans from the mainland.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh boy.

Guy Kawasaki: For the first time, which...you know the term katonk?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yes.

Guy Kawasaki: Okay.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Absolutely.

Guy Kawasaki: So first time I ever met these katonks, right, I could not relate to them at all because, justifiably so, they had a chip on their shoulder about being Japanese, racial prejudice, internment, all this kind of stuff. And I was from Hawaii.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: And you're the majority.

Guy Kawasaki: I'm the majority, from a fairly powerful family in Hawaii. I could not relate at all, to all this victimization stuff. It was an eye-opening experience for me also.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh, for sure. It's amazing that they even talked to you about it because for years, they just never talked about that experience. And that's why Farewell to Manzanar, when Farewell to Manzanar came, it was like, people were stunned that that had ever happened in my age group.

Guy Kawasaki: Were they angry that you wrote that book? And lifted up?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Who? Well, you know what? No, they weren't angry, but I think that they were just like, "Oh, don't bring the attention again. Don't bring it up," and everything. But because the response by then, by the populace and everything, was much more positive, and about they're indignant, and actually, we owe it to the Black Power movement, because the Black Power movement was first. The Black Power movement…

Guy Kawasaki: The Olympics.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: ...and then brown and then Asian. So Farewell to Manzanar fell into that historical time. So when the book came out, easy to read, and it was a book that...We knew, my husband and I knew, "Listen, you cannot make people feel guilty, because they feel guilty, they get mad. They get the opposite reaction." We knew that we had to tell the story that people would read, and could relate to in their heart. "This is a young girl. She's an American. Did we do that?" And so forth. So that it's readable, and that people are not going to have a knee jerk reaction. So we had great purpose. And I don't know if you know this, but it's part of the story. My husband never knew about the camp.

Guy Kawasaki: Your husband did not know about Manzanar?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: And we had been married fourteen years. We knew each other for, I forgot...It was fourteen years, but the kids were already born, and we just...I never talked about it. Nobody in our family did. It was a secret. Because it was such a shame, you know?

Guy Kawasaki: Why was it a shame? You were the victim. You didn't cause the shame.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh no, no. It was a shame because we didn't have enough self...What is the word? Self-pride, to realize that, "How dare they do this to us?" No, because we were just at the end of one hundred years of anti-Asian racism in California. So my father would never go into a restaurant because I think he experienced not being served or something there, and he was a very proud man. Never would go into a restaurant. It was very hard for the Issei, that's my father's generation. They were what they called a Chinese hoard that came in. Well, the Japanese were right in there with that. And tremendous anti-Asian, which Hawaiians would not understand, because you are the majority.

Guy Kawasaki: Not at all.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: You are the majority. You're in power there. And I know, my mother is from Hawaii and I go there. She went to school there. She went to university. And also for the 442nd, I mean, go for broke. They're Hawaii boys, because they had a lot of guts, because they had self-esteem, because you could get that in Hawaii. Not on the mainland. And so it was tough, with these boys who came from Hawaii, and they see these, how the Japanese were so different. Those katonks were so different than they were. Because they were the majority.

Guy Kawasaki: Didn't your brother go into the army though?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yes.

Guy Kawasaki: And can you explain that to me? So this government just put you in a concentration camp, and now you volunteer to fight?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: He didn't volunteer. He was drafted. Oh, they drafted... I mean, it was crazy. Not only, they drafted him, but he couldn't speak Japanese that well, but they pluck these guys out with a high IQ, whatever it is, and he was trained in... Well, he was in MIS. He became one of those military interpreters, and learned Japanese really well. And he was one of the first to go over to Japan right after, with MacArthur, right after the war.

And he was... When I think of it now, the irony of it because my father never could afford to go back to Japan, but his son does. And his son, my brother, goes to Hiroshima, and sees the great aunt, sees the graves that my father's family are in. My father used to talk about being from a samurai class, and we never paid any attention to it, but it was true. His relatives are buried in Miyajima. Hiroshima, that island off there. And so my older brother, it was such an experience for him, pride, in that he was somebody, and not a second class citizen, like you're treated here in this country. But when he went back to Japan, he saw his roots. He never believed my father.

Guy Kawasaki: He was drafted. He was still serving the government that put his family in a concentration camp.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh right. Yes.

Guy Kawasaki: I have a hard time wrapping my mind around that.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Because what else could they do? I don't know of anybody that refused to serve, and there were some other, but they called them, they were Kibei. They were the educated, Japanese Americans who were educated in Japan, and they were very pro-Japan. And they came back. They were very educated, very smart. They knew about racism. They became the ones who marched and everything.

And so the other Japanese, who were not of that education and so forth, stayed away from, because these guys were trouble, because they acted like the stereotype of the Japanese soldier, or very Nazi. They would march around camp like--

Guy Kawasaki: Wait, wait. They would march around camp in support of Japan?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki: Inside Manzanar?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki: Wow.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh yeah. There was tremendous friction because a lot of the educated Japanese said, "Why should we stay in this country that treats us like this? They don't want us here." But then someone like my father, who was educated in both countries, he said, "It's never going to be the same if you go back." At one point, they said, "Okay, if you sign this loyalty oath, and you sign it yes-yes, or no-no," then that would determine what would happen to you when the war was over and so forth.

So there's a huge friction within the camps of people because then they started saying, "No, we're going to vote as a block, and not as an individual." And that's when I remember my father really speaking up, and just saying, "No, we get the individual, not as a block. I'm not going to vote..." And here he was from a samurai class in there. He said, "I'm not, quote, going back to Japan. My children and I will stay here."

Guy Kawasaki: So just for clarification. So yes-yes means you're loyal to the United States, right?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki: And no-no meant…

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki: ...to Japan.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: That's why they call that no-no boys. Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki: It's now a long time after this.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: It was. Yeah. It's a wonder that... I haven't even thought about this for a long time.

Guy Kawasaki: Eventually through the court system, and probably through the efforts of lots of white people...

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh absolutely.

Guy Kawasaki: …the camps were closed.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh yeah. They knew it was a mistake, but they've been doing it to the Native Americans. This is our MO, was the United States would do this, just round up people and put them away.

Guy Kawasaki: What's your attitude now towards the United States government? I mean, have you forgiven them for what they did?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: I don't know if it's about forgiving them or anything like that. I'm very active politically. And I will tell you, Trump, he's bad news, very bad news, because he appeals to the worst part in people's self, you know, their psyche. They have to have someone below them to beat, and that's what he appeals to.

Guy Kawasaki: But focusing on what happened eventually with Manzanar and the camps being closed, and you guys going back into society even though you were in camps, I mean the Terminal Island and Cabrillo, is the glass half empty or half full? Half full would mean that, well, eventually the system kicked in and we were freed, or half empty would say, it should have never happened.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh, of course half empty. It should never have happened. But the fact of the matter is, it has happened in this country because it's part of our historical personality of a country.

Guy Kawasaki: Do you think it could happen again, to Muslims and Mexicans?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: From my own point of view as an educated person, I think, well, it could happen, but we were not going to let it happen. Oh, it's trying to happen all the time, but you have to have people who understand, and who know, and who understand the psychology of hatred, and the psychology of not having, and then somehow if you scapegoat another group, it somehow gives you, either some feeling of worth or... It's to squelch another group, so that you can rise above it.

And so it's really a deep, psychological thing that the human being has. If we could be a perfect human being, and love ourselves, and not have to put down someone else in order to elevate yourself, then we can go smoothly along, and I think we're getting there to some point. At least we can articulate that.

But then you have someone like Donald Trump who comes, and who's a little psychologically off balance. And sometimes these people are very charismatic because they're crazy. That's very charismatic. And you get to someone who says things that is so off the wall and then say, "But wait a minute." Because it's so off the wall that you start to study it, or to look at it, if you yourself don't have a strong feeling and vision of your own worth.

Guy Kawasaki: That's easy for me to say, but when you were imprisoned, they took your whole family, and they stuck you in a camp as a family. Family separation at the border today is unconscionable. I don't know how you can justify that to yourself. And they claim to be Christian. Could you foresee, let's say there's an act of terrorism by Muslims in America, right? Round up the Muslims, stick them in camps?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh totally. It's always there.

Guy Kawasaki: You could see that happen today?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: I could see that it would try to happen, but there'd be a lot more people who are educated, who know about that. I know that the Japanese who know about the internment, out of principle, would speak up. The JACL, because this is what they do all the time. They're looking at this, they're looking for this, what the danger signs are, and for sure it's against Muslims. We know that.

Guy Kawasaki: Do you have any thoughts about how we can prevent this from happening again?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Well, it's just education. And when I speak, I'm open for question, and we always get into this kind of discussion. And to put that into... This could happen again when you start looking at people, you're not seeing individuals, and you're seeing this as a group.

Guy Kawasaki: That's a key insight. So you're saying that Roosevelt or whoever said, "110,000 Japanese are all the same, and..."

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Oh yeah, of course they thought that. Because they look the same. They have slanted eyes or whatever, and it's just simplifying things. And well, if you think about it from a psychological point of view, I mean, Hitler was so crazy, and all the hatred and so forth that went on with the Nazis, and so you just look at what the bottom line, psychological weaknesses.

And I would say that with Trump today, he tries to appeal to white people, or to a group of people, to make them want to feel like they're above it because it makes them feel like they're it. By hating someone else, and putting someone else down, that they elevate themselves.

Guy Kawasaki: I cannot relate to the mindset that, in order for you to succeed, other people have to fail. I believe that the rising tide floats all boats.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Absolutely, because I don't know... Do you have brothers and sisters?

Guy Kawasaki: I have one sister.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: One sister, and you were raised in Hawaii?

Guy Kawasaki: Yes.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: And probably very loving parents?

Guy Kawasaki: Yes.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: That's where it comes from. It comes from that basic, when you're young, growing up, and about the basic love, and it starts with your brother and your sister and your mother and your father.

Guy Kawasaki: What if you didn't have that though? What if you're 50 years old today, and you didn't have that, and you are, you are thinking Mexicans and Muslims are all rapists and terrorists?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: That's because you were deprived.

Guy Kawasaki: But it's too late to go back in time. So what do you do with that fifty-year-old who believes that? That, "I'm poor because the Mexicans and Muslims are taking my jobs, and..."

Jeanne Wakatsuki: You know what? I think you have to reach those people emotionally, psychologically, in their hearts, because I have found, and I have spoken to a lot of people from all over this country, and I have found that most people, unless they're really damaged, they really do want to love. They really do want to accept you. And so if you give them that way to do it, they can break into tears.

I've had people come up to me and say, "Oh, I never knew about this," or something like this. And they're just in kind of shock. And I reach out and hold their... I said, "It wasn't your fault." I said, "But you'll never let it happen again." And they just start crying because they really do assume that it was their fault. And that's what I have to be careful of, because you don't want to leave people feeling that they have wronged somebody, because you never know how that guilt is going to turn on itself.

Guy Kawasaki: With all your travel and speaking, do you think people are more different or more the same?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: I have been to so many different places. It's amazing, the response people... Like when I was in, was it Missouri? Arkansas and places like that. Maybe it was the people who I spoke to, who would come to hear that.

Guy Kawasaki: The self-selection, yeah.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: People go to church and things like that. They were the nicest people, and when they heard that the writer was coming to their town, they got their whole families together, dressed up like they're going to Sunday school, because they've never seen a writer, and they came. They were so polite, so nice. Thinking to myself, "Wow. But it's this group here that forced ahead with the internment." But their children and their grandchildren were so, what I would call, good Americans.

They knew it was wrong, what had happened. And yeah, I was very shocked and impressed. Because I was scared to go, at this time when I did that, to go to these, Missouri and places like that. It was okay, New York, Maine, or the West Coast. Texas, I'm afraid to go there. I'm afraid to go to the South, still.

Guy Kawasaki: Still?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki: Even after you said they were kind and all that?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Because they can't make the difference between if I'm a Chinese from China or Japan. It would have to be incredible education to these people about the Second World War, and the Japanese Americans being interned.

Gabby Houston: Glenn Beck wanted to interview Mom.

Guy Kawasaki: Glenn Beck wanted to interview you?

Gabby Houston: Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki: And?

Gabby Houston: She was set up with an interview with Glenn Beck, and we knew that the angle that he wanted to take was that, she was going to be really bashing on the U.S. government, because he was so anti whatever he wanted to bash on that year.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: That's right.

Gabby Houston: Remember that Mom?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yeah.

Gabby Houston: We were like, "What is the angle? Why would he want to interview Mom? She's the opposite of what..."

Guy Kawasaki: He is.

Gabby Houston: What is his angle? What is he getting? What's going to happen here with this interview? And so the interview never happened, but I remember you were like, "Oh, he's going to be shocked at what I have to say," because you had such a different spin, a different take on your thoughts on democracy, and being in this country, and you were…

Jeanne Wakatsuki: That's right. That was so long ago.

Gabby Houston: Remember, and even though you went through what you went through, as a child at Manzanar, you said if it had happened in any other country, it wouldn't have come out the same. Because at least now it's a country that recognizes it.

Guy Kawasaki: Even if it would have happened, it would come out worse, you mean?

Gabby Houston: Yeah. It would come out... Like if you're in China, or another--

Jeanne Wakatsuki: You'd be dead.

Gabby Houston: You'd be dead, or the country would never acknowledge it.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Or recompense you, I mean, they paid damages and so forth.

Gabby Houston: Here at least a book came out, and now it's out. My assistant coach is from the Ukraine. She's never heard of Chernobyl.

Guy Kawasaki: She's never heard of Chernobyl?

Gabby Houston: She's never heard of Chernobyl. She was born and raised in Ukraine. She does not know where Chernobyl--

Guy Kawasaki: What was the reparation?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: That every individual who was interned, no matter what your age, you got a check from the government for $20,000.

Guy Kawasaki: What did you do with that money?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: What did I do with that money? God, I don't know. Did we go out and...

Gabby Houston: Did you ever get it?

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Yeah, I did. I forgot what I did.

Gabby Houston: You were one of the last--

Jeanne Wakatsuki: That was a lot of money to my husband and I. We're not of the affluent.

Guy Kawasaki: I hope you spent it on something good. I'll tell you a funny story. So I was in Mobile, Alabama. You can't get much deeper than that, right? And I was well known in the Macintosh community. So I went to a Macintosh user group in Mobile, Alabama. Okay? And this white guy, he says to me, "You know Guy, I was born too late for slavery and too early for robots." And I sat there, and I thought, "This guy has no idea that I'm not Bubba or Junior of one of him." I'm like, "I may not be black, but I’m not exactly white."

And I learned a very valuable lesson that day, which is that people can focus on what separates them, or you can focus on what brings you together. And that guy said, "Guy, who is not white, but he loves Macintosh, and I love Macintosh, so we can be friends." It was a very valuable lesson. If I didn't like Macintosh, or he didn't like Macintosh, maybe we could not be friends, we might even be enemies. So one of the lessons I learned in my life is, always try to find something in common.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: Of course.

Guy Kawasaki: As opposed to where you're differ.

Jeanne Wakatsuki: The differences, yeah. Yeah, that's a very, very good way of looking at things. You don't hear that much. It is about accept and immortalize your differences. Everybody wants to say, "Oh, you're different. That's wonderful." But then the spiritual thing is about the sameness of it, that part of us that understands each other, because it's the spirit that goes through all of us, that is the basis of our soul.

Guy Kawasaki: I hope you learned a lot from Jeanne's story. Many people are not aware that Japanese Americans were interned during World War II. May her story ensure that this never happens again. I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. My thanks to Jeff Sieh, and Peg Fitzpatrick, my remarkable podcast team. Thanks to Terry and Will Mao. Thanks to Gabby Houston, Jeanne's daughter, for making this happen. Be safe, be healthy, wash your hands, maintain a distance of at least 10 feet from people. Until the next episode, take care. This is Remarkable People.

Sign up to receive email updates

Photos courtesy of Wikimedia: Cover photo – Manzanar War Relocation Center – photo Ansel Adams, from the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA, http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/ppprs.00276

Manzanar War Relocation Center, mid-1940s, Picture taken from guard tower, summer heat, view SW

One winter day’s stay – windswept icy dusty day – be the root of change. The men who volunteered to fight for the USA have more grit than Rooster Cogburn. Thank you for your brave service.

– Michael Petersen

I found this story so relatable and authentically told. My grandfather was at Manzanar and I recall being surprised to hear it as he never discussed it. (I was assigned to read it at my public elementary school here in CA.) Thank you for this interview… first person history is so important to preserve and pass on, esp. to younger generations—lest we forget how far we have come, and where we might go.