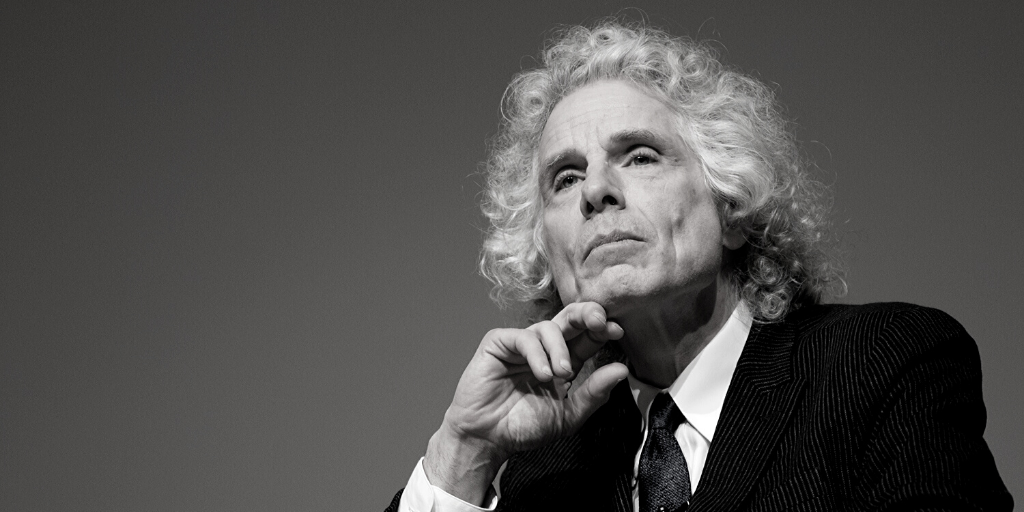

This episode’s guest is Dr. Steven Pinker. He is a Harvard professor of cognitive science (the study of the human mind) with expertise in visual cognition and psycholinguistics as well as an author and speaker. He writes about language, the mind and human nature.

Recall my interview with Dr. Stephen Wolfram a few weeks ago. Steven Pinker is to social science what Steven Wolfram is to math and physics. In other words, off-the-scale, intimidating insightfulness, and intelligence.

My interpretation of Steven is that he’s all about science and facts. Politics, religion, tribalism, nostalgia, and wishful thinking do not influence much less cloud his judgement. If only more people in leadership positions were like him.

Which is to say that to Steven, the sky is neither falling nor cloudless and blue. It is what it is. Keep listening if you want to learn about the most important tools for an informed and intelligent electorate.

Question of the week!

This week’s question is:

Do you think we can improve our society? What would that look like to you? #remarkablepeople Share on X

Use the #remarkablepeople hashtag to join the conversation!

Where to subscribe: Apple Podcast | Google Podcasts

Follow Remarkable People Guest, Dr. Steven Pinker

Follow Remarkable People Host, Guy Kawasaki

I hope you enjoyed this interview with Dr. Pinker. Prepping for this interview, like the one for Steve Wolfram, almost made my head explode.

I hope that this interview helps you approach decision-making in scientific, fact-based ways. That’s how we’ll get through these difficult times.

I’m Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. My thanks to Jeff Sieh and Peg Fitzpatrick for their awesome work in helping me deliver this podcast every week. My mahalo to Sasha Andreas, quote/unquote, a random French guy who introduced me to Steven.

Guy Kawasaki: This episode's guest is Dr. Steven Pinker. He's a Harvard professor, with expertise in visual cognition and psycholinguistics. He's also an author and a speaker. I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. And now, here's Dr. Steven Pinker. Guy Kawasaki: Guy Kawasaki: This is Remarkable People.

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People.

It's April 2020, and these are going to be some difficult times. I hope that you and your loved ones are safe and healthy. Remember to wash your hands and maintain a good distance from people. By the way, six feet may not be far enough based on a MythBusters video that I watched. Google: MythBusters flu, to find it.

My theory is that if you're near someone who sneezes or coughs, hold your breath and get away. I'm over 65, so I am even more careful. I have been in voluntary quarantine for twenty days now.

Recall my interview of Dr. Stephen Wolfram from a few weeks ago. Steven Pinker is to social science, what Stephen Wolfram is to math and physics. In other words, off the scale insightfulness and intelligence.

My interpretation of Stephen is that he's all about science and facts. Politics, religion, tribalism, nostalgia, and wishful thinking do not influence, much less cloud, his judgment. If only more people in leadership positions were like him.

Which is to say that to Steven, the sky is neither falling nor cloudless in blue. It is what it is. Keep listening if you want to learn about the most important tools for an informed and intelligent electorate.

I want to go down a little bit of a rat hole. I heard a lecture of yours, and I'm curious because I have Meniere, which involves hearing loss. How would you test hearing? You basically condemn how it is tested.

Steven Pinker:

There are a number of techniques that have been developed by perception psychologists to separate sensitivity from response bias. The problem I was alluding to is that, in the traditional hearing tests, you present a series of beeps that are increasing in volume, and you have the person raise their finger, when they start to hear it. Then, you've got a zone in the middle where people are asking themselves, “Well, I kind of think I hear it. Should I say ‘yes’? Should I not?” What you're picking up there is as much personality and confidence and willingness to raise your finger and say, “Yes,” as you are the sensitivity of the auditory system.

It's a problem that was solved more than a hundred years ago with perception research, and I was stunned to see that my doctor was still using that test. But even something as simple as you can hear the tone in the first second, or the second, as you make it a forced choice so that you always have to give a response and the subjective aspect of, “When do I go on a limb and say, ‘I've heard it,’” is eliminated.

Guy Kawasaki:

So let's dive in. Because of your background and about rationality and nostalgia and reasoning and all that, I really want to know your analysis of the reactions and actions we're taking to the Coronavirus.

Steven Pinker:

Well, it's been said many times and far better than I can say it, that the response of the president of the United States is quite extraordinarily incompetent and irresponsible, given the magnitude of the potential threat. We have no idea how it will play out, but we know that because of exponential growth, it could overwhelm our medical defenses more quickly than we would like.

The beginning of a pandemic makes it incumbent on us to act aggressively and quickly because exponential growth can overwhelm anything, and by seeing this challenge in terms of Donald Trump's own command of the world, that is whether good things or bad things are happening on his watch, tried to minimize the seriousness he is putting in the nation and indeed the more at-risk in downplaying it simply because he thinks it reflects badly on him.

This of course has been the methodology of the entire Trump presidency, is that his own ego supersedes his fiduciary responsibility to the wellbeing of the country that he's presiding over and we're seeing it in an extreme form in response to the first major domestic emergency in his presidency.

Guy Kawasaki:

And how would you describe this syndrome of what he's doing?

Steven Pinker:

Well, it is a form of a pathological narcissism. A combination of a grandiosity-- that is, everything reflects on him, the lack of empathy, but there doesn't seem to be any particular concern for the potential hundreds of thousands of victims. The need for admiration, an affirmation that crowns out all other motives. So we're seeing, again, I hardly originally pointing this out, but the malignant narcissism that can characterizes Donald Trump, that his personality is, as everyone feared, manifesting itself in carrying his decision making.

Guy Kawasaki:

What about when you hear an analysis like people saying, “60,000 people a year die from the flu, only a few dozen of them die from this. What's the big deal? Why are we so concerned about this, and why don't we take the same kind of reactions with the flu?”

Steven Pinker:

Because of the possibility of exponential growth. This is far more deadly than the flu. We don't have a vaccine for it and because things that grow exponentially can overwhelm any finite limits.

I even looked to a history of the Spanish flu which created a major reversal and the overall trend of increasing lifespan. You look at a curve for global life expectancy, it shows a huge dip around the time of the Spanish flu. So epidemics, pandemics have the potential of causing massive death and much depends on how quickly they're nipped in the butt.

Guy Kawasaki:

From an academic standpoint, the phenomena of saying that the flu is worse than this so what's the big deal, is an act of pure ignorance or denial or lack of the depth of analysis?

Steven Pinker:

All of those, yes. It's a failure to appreciate a basic feature of the replication of pathogens, mainly that it can be exponential.

Guy Kawasaki:

Using this as a case study, let's say someone watches the news. How does one discern that, this person Donald Trump is saying "No big deal, we have it under control", this person says "Pandemic, exponential growth.” How do people decide what to believe?

Steven Pinker:

Well, it is certainly reasonable to trust people who, one thing, don't have a vested interest in minimizing it, whose interests are aligned with objective understanding and with public welfare. And of course, people who have expertise in the subject matter, that is epidemiologists, ought to be given greater credence than that than politicians, unless they take the advice of the most informed epidemiologists.

Guy Kawasaki:

In general, are you saying consider the source? I mean, that's for the lay person.

Steven Pinker:

Absolutely. Consider the source. Now, of course, this doesn't mean putting one's trust in on anyone who wears a white coat and calls himself or herself, an expert. On the other hand, if people have the legitimate credentials of understanding a problem, mainly they have spent their lives on it, they've been trained in it, they've published it, they're on top of the latest data. If in addition, they don't have any particular vested interest in either minimizing or maximizing it, but their own interests are aligned with the truth and with public welfare, they are the ones that have earned the most credence.

Guy Kawasaki:

I've wondered this more and more because of Trump and the virus. Could it be that we truly are living in a simulation and someone is just playing with us and said, “Well, let's inject the narcissistic leaders, see what happens. Now let's inject the flu and see what happens?”

Steven Pinker:

No, I don't think we're in a simulation. These things can happen in reality. There's no reason, there's nothing that would prevent them. There is an enormous common notarial space of possibilities for how events can unfold in the real world, and there's no reason to think that surprises can't happen.

There's just so many ways that surprises can happen. It would be, the most surprising thing of all would be, if there were no surprises. There're just lots of things that can happen. We know that there are lots of ways in which an election can be influenced, there are chaotic processes in terms of when a pathogen can acquire greater virulence, the population dynamics of what needs a pathogen to, as we say, “go viral” in the original sense.

We know that the precious and difficult to understand initial conditions can be the difference between a disease becoming a pandemic or not, that this is, quintessentially, the kind of process that can go out of control. You shouldn't be shocked if every once in a while, it doesn't go out of control. It's certainly doesn't mean we're living in a simulation. It's all too real.

Guy Kawasaki:

Switching to the topic of nostalgia. I think you're saying that nostalgia is usually overrated. Were there any significant periods where the past truly was better?

Steven Pinker:

Across the board? Probably, not. If that is, if you ask the question of, if I was to be incarnated as a randomly selected person on earth, there's no better time than the present. That is, if you asked the question originally posed by John Rawls, of what kind of world would you want if you were deciding behind a veil of ignorance as who you would be, you didn't know if he'd be born in Africa or Asia or Europe, or if he would be rich or poor, or a male or female, then playing the odds here, you're better off now because people live longer.

A few people starve to death, fewer people die of infectious disease, more people are literate. So there were particular aspects of the world that were better in the past, such as ecological diversity, the abundance of efficient water, the number of species, the quaintness of towns. There are certain things that you can point to, but anything that you could measure quantitatively, just about, is better now than in the past. Pretty much at any time in the past.

Guy Kawasaki:

How did nostalgia come to be overrated?

Steven Pinker:

There are features of human nature that make us nostalgic, such as that when it comes to our own memory, we often tend to forget how bad things were while we were living through them. We tend to, for example, people remember the smaller degree of inequality in the 1970s, but they tend to forget the shortages of meat, coffee, and sugar. They tend to forget the lines around the block to the gasoline. They forget the fear of running out of a heating oil and natural gas. They forget about what was called the misery index, that is the combination of the inflation rate and the unemployment rate, both of which were in double digits at the same time.

There are facts that people forget. But even in our own autobiographies, when we think back on what it was like to live through those eras, those of us who didn't live through them, we are inherently most colored. We forget how much anxiety there was over the fact that even if you did pay the rent this month, you don't know if the rent was going to go up next month faster than the paycheck would. We forget that anxiety, that kind of anxiety. So that's one reason.

There's also an incentive for people to denigrate the present and romanticize the past. It's a form of social competition as Hobbes put it, men contend with the living, not with the dead. To criticize the present is a way of criticizing your rivals.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let's suppose that we come to the understanding that nostalgia is overrated. Can that lead to present day denial? So in the sense that we could say, "Well, we're not lynching black people anymore, so what's the big deal about stop-and-frisk? Stop-and-frisk is so much better than lynching black people, let it go."

Steven Pinker:

Well, that doesn't follow because if something has decreased, that doesn't mean it's disappeared. Things could be better without being acceptable. Quite the contrary, you can empower us to try to eliminate the injustices and deprivations of the present, knowing that our predecessors succeeded when dealing with the ones they faced in the past.

It means that trying to improve our lives, trying to improve society it's not romantic, it's not utopian, it's not idealistic. It can work. It has worked in the past and so it can continue to work in the present.

Guy Kawasaki:

There's a thread, I think, in your work that some of our current behaviors is negative and dooming us. Is this because evolution isn't the straight and smooth path and we have to take a longer view? I mean, there're some things that we've evolved to that are not good right now, right?

Steven Pinker:

Evolution, in the biological sense, occurs slowly by a human scale. It's got a speed limit measured in generations, and the changes that we see around us virtually none of them are evolutionary, at least the changes in ourselves. The changes that we see in organisms that do produce more rapidly, like the Coronavirus, are significant, but that's because they reproduce over a span of minutes rather than decades and so evolution is a speed it up that much more in those cases.

Over a span of a few generations, we're stuck with the human nature that has evolved up to this point. But really, the human nature has given us a lot to work with. It's given us some rather unfortunate motives. It's given us cognitive limitations like self-centeredness, self-deception, overconfidence, confirmation bias, reasoning by anecdote, magical thinking.

On the other hand, it's also given us an open-ended combinatorial symbolic system of thought. We can think new thoughts, sometimes there are analogies to old thoughts, but we can put them together in new ways. We can use mathematics to come up with new relationships that our ancestors didn't appreciate. We've got tens of thousands of words in the language, which we can assemble into new sentences than they knew thoughts.

So we do have the cognitive processes to think up new solutions. We also have, together with our rather ugly emotions, our lust, our greed, our desire for revenge, we do have some better angels of our nature. As Abraham Lincoln put them, we have a sense of empathy, we have a capacity for self-control, we have the ability to conform to moral norms, things that a decent person just doesn't do, and we can take what evolution gave us to work with, mainly these cognitive and emotional faculties, and make our best case for how to deploy them, to solve the problems facing us now, share the solutions.

Guy Kawasaki:

Can a case be made that a negativity bias helps us prepare for the worst case instead of expecting the best case? Can a negativity bias work to our benefit?

Steven Pinker:

It depends on how much of a bias it is as opposed to monitoring reality. Clearly, you don't want to deny the negative, you've got to be sensitive to it, otherwise, you'll wander into disaster.

You need to be in touch with reality, and probably some bias toward the negative is necessary, given that there are more things that can go wrong than can go right. The things that could go wrong can hurt us far more than the things that go right and help us. So it is rational to be more vigilant to threats than to windfalls, the threats that can kill you and they can kill everyone else, the windfalls can benefit you somewhat, but not nearly as much as the threats that can harm you. The bias should be calibrated by the harm and the probabilities of the threats and they shouldn't be so biased that we are mistaken about the reality of the world, about how much improvement we have enjoyed.

Another way of putting it is to set the bias, ordering to the costs and benefits of action and inaction, but we shouldn't be inaccurate in terms of our best assessment of the probabilities. We can choose to take out insurance, we can assure it, choose to be cautious, to err on the side of caution, we shouldn't delude ourselves as to what the threats are or what we have accomplished so far.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let's say that a candidate for the presidency that you approve of, or support, contacts you and says "Steven, based on all you know about negativity bias, about evolution, about social psychology and reason and rationality and nostalgia, everything you know, tell me: how do I win this election?"

Steven Pinker:

I would say the Peter principle, according to which everyone rises to their level of incompetence in space, that would be an example of the Peter principle applying to me. Although to be honest, I actually have been in touch with two of the former, the candidates for the democratic nomination, I do know two of them personally. I have spoken to centrist politicians in other countries, in Canada, in Colombia and I don't offer them strategic advice on how to run elections because I don't know and I would not venture unsubstantiated guesses.

I don't offer them advice on particular policies, how best to achieve economic growth, but I do share with them a vision of what governance ought to be for those who are not Marxists, to those who are not populists, to those who believe that there is a positive role for government to play in a liberal democracy. That there has been a constructive role for government, both within countries and organizations of international governance, like the United Nations, the International Criminal Court, the OACD, and other ways in which nations cooperate, and offer a more of a bird's-eye view that just affirms the value of, in general, the liberal democratic vision.

Something that I do think that I have a role to play there and I can back it up. It's saying that the structures that we have in place have achieved, basing things like reducing extreme poverty to less than eight percent, reducing illiteracy to less than ten percent, people under the age of twenty-five to drastically reducing the rate of death at warfare.

To give a boost to the very idea that the democratic governance is a good thing; it's positive, it's an ideal worth defending. An era in which liberal politicians are often just seen as wishy-washy defenders of the status quo. The emotional energy tends to come from the firebrand populace on one side and the socialists hearing into Marxists on the other side, and no one is willing to actually say anything good about mainstream liberal democracies. I do see a role there.

Guy Kawasaki:

If Joe Biden said to you, “So how do I get from here to there?” What do you say?

Steven Pinker:

Well, I would not offer policy advice in areas where I'm not a policy expert. That is, what is the best way to, say, reduce the people who are out of the workforce. What of the best public health strategies to minimize the chance of future pandemics? There you have to ask the economist. You have to ask the epidemiologists.

In the case of energy, I do have an overall set of guidelines to how to deal with the climate crisis. I do think that we ought to concentrate on making clean energy cheap so that people will work toward saving the planet while favoring their own interests that I don't think that either calling for voluntary conspicuous sacrifices nor denying the reality of climate change, nor demonizing fossil fuel companies are ways that will get us to where we want to be a zero-carbon economy. So offering that generic advice, but whether it should be mostly nuclear, whether it should be renewables plus storage, there may be the experts in energy technology.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. I tried to get it out of you anyway. What are the most important principles and tools that an informed electorate should learn?

Steven Pinker:

One would be an open-minded, evidence-based mindset that is rather than healing in our bones, that there is a policy solution, that the way to reduce school shootings is to have stronger gun control laws. Maybe yes, but maybe no.

That what we ought to do is foster a robust social science, the innovative ways of using your datasets, try to extricate ourselves from left-wing or right-wing mindsets that dogmatically push one solution to problems. Often just encouraged by people playing things out in their imagination. “I think this would work. It makes sense to me that it would work. I can envision it working.”

Reality is so complicated that we ought to be prepared to be humbled, we ought to listen to people from other ideological camps. Hold their feet to the fire in bringing forth evidence that supports the efficacy of their programs, but to tilt our discussion more in the direction of a scientific mindset and less from a sports mindset around winners and losers and teams and opponents.

Guy Kawasaki:

But today, my perception is: science is absolutely being trampled upon. I mean, the thermometer is not a liberal or conservative, but…

Steven Pinker:

Quite right, most people agree with you. That is a majority of people in virtually every country believe, for example, except the scientific consensus, that there is climate change and that is caused by human activity. There are ultra-powerful factions that deny it, but by no means do they speak to the majority of the population.

So we do have a problem in democratic governance so that governments can be captured by minority factions, but we need to bring the appreciation of science that is fairly widespread, people do respect scientists more than almost any other profession, and to take advantage of that, to give it a greater role in our policy-making in political decision making.

Guy Kawasaki:

By any chance, did you see yesterday's press conference about the Coronavirus with the Trump and Pence?

Steven Pinker:

I did not see it live. I read about it. My capacity for massive consumption of news at home can go so far.

Guy Kawasaki:

And for my last, truly my last question. Do you know who Stephen Wolfram is?

Steven Pinker:

Yes, I do. I know Stephen Wolfram.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you hold him in high regard?

Steven Pinker:

Yes, I do. That doesn't mean I believe in everything he says, but I absolutely hold him in high regard, yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

I asked you those two questions before I tell you this. So I interviewed him for this podcast and I can interview him once every ten years, because I need to rest between those interviews.

Steven Pinker:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

I offer this therefore, because I hold him in the highest regard. I offer this to you as a closing, positive note. That in doing the research for this podcast, watching your lectures, YouTube’s, and reading your books, I have come to the conclusion that you are the Stephen Wolfram of social science, and there is no higher form of praise than that for me. I want to thank you for doing this and someday I hope to attend one of your lectures in-person.

I watched your Harvard lecture and I said to myself, "That's why you didn't go to Harvard, Guy, because you couldn’t possibly understand that.” So thank you very much, Steven.

Steven Pinker:

That’s very kind of you, Guy. I enjoyed it. Thank you for having me on.

I hope you enjoyed this episode with Dr. Steven Pinker. Prepping for this interview, like the one for Stephen Wolfram, almost made my head explode. I also hope that this interview helps you approach decision-making in scientific, fact-based ways. That's how we'll get through these difficult times.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. By thanks to Jeff Seih and Peg Fitzpatrick for their awesome work and helping me deliver this podcast every week. Also, my mahalo to Sasha Andreas, quote unquote, "A random French guy who introduced me to Steven".

Until next time, be safe and be healthy.

Sign up to receive email updates

I didn’t understand most of this interview!

Hi I read and heard Interview of sir Dr. Steven Pinker I like him very much.first thing is I like Psychology very much and this interview is really wonderful.

Thanks