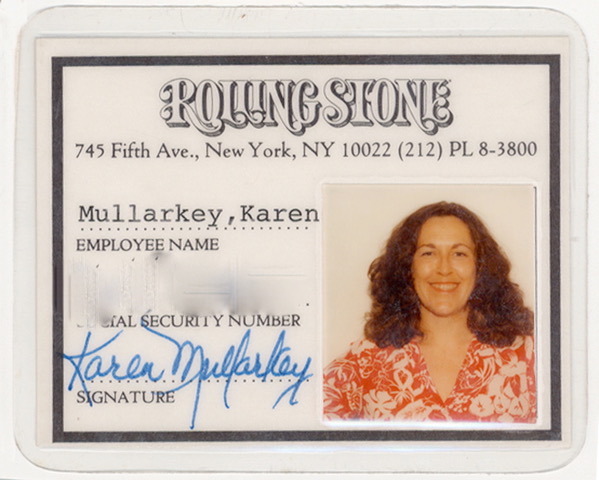

This episode’s guest is not merely remarkable, but she’s been called a “national treasure” because of her work at Life Magazine, Newsweek, Psychology Today, Sports Illustrated, and Rolling Stone.

Her name is Karen Mullarkey. She launched the career of many of the most famous photographers in the world. You’re going to hear stories about Annie Leibovitz, Richard Avedon, Gordon Parks, Herb Ritts, Anna Wintour, and Katharine Graham.

Her interview was so remarkable that I created a list of references to the people and topics that she mentions. You can peruse the list here.

I conducted this interview by phone while she was vacationing, so you’ll get to hear the cardinals chirping in the trees and the answering machine ringing where she was staying. When is the last time you heard an answering machine ringing???

Here’s a challenge for you. If you know of anyone who has pictures of two women at Christo Vladimirov Javacheff’s “Running Fence” in June or July 1976, those pictures may have been taken by Richard Avedon! It would be epic to use social media to find the pictures.

I know you’re going to love this interview with Karen Mullarkey, the national treasure of photo editors.

This week’s question is:

Do your current habits support the person you wish to become? What advice will you take from Karen to excel in your career? #remarkablepeople Share on X

Use the #remarkablepeople hashtag to join the conversation!

Where to subscribe: Apple Podcast | Google Podcasts

Learn from Remarkable People Guest, Karen Mullarkey

Follow Remarkable People Host, Guy Kawasaki

Guy Kawasaki: I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People. And now, here is Karen Mullarkey. Guy Kawasaki: That's it. Wow, wow. Oh my God, wow. It is review time, one of my favorite times of the week. This is Remarkable People.

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People.

This episode's guest is not merely remarkable, she's also been called a national treasure because of her work as a photo editor for Life, Newsweek, Psychology Today, Sports Illustrated, and Rolling Stone. Let me repeat that list-- Life, Newsweek, Psychology Today, Sports Illustrated, and Rolling Stone. Her name is Karen Mullarkey.

She launched the career of many of the most famous photographers in the world. You're going to hear stories about Annie Leibovitz, Richard Avedon, Gordon Parks, Herb Ritts, Anna Wintour, and Katharine Graham.

Her interview was so remarkable that I created a list of references to the people and topics that she mentions. You can peruse this list at the Remarkablepeople.com post for this episode.

I conducted this interview by phone while she was vacationing, so you'll get to hear cardinals chirping in the trees and the answering machine ringing where she was staying. When is the last time you heard an answering machine ring?

Here's a challenge for you: If you know of anyone who has pictures of two women at Christo's Running Fence in June or July 1976, those pictures may have been taken by Richard Avedon. It would be epic to use social media to find those pictures.

What exactly does a photo editor do?

Karen Mullarkey:

You wear many hats, okay? If you're running a department like I was, part of you is like a matchmaker. When you're assigning a photographer to a particular story, you're looking for not just their ability as a shooter, but you're looking to match their personality into what you perceive to be the personality of the subject. And really, what you're dealing with is a level of casual intimacy.

You're making a short-term marriage, and when you make the right combination, the work is spectacular, because the subject immediately relates to the photographer. The photographer gets who the subject is, and they form this intimate relationship.

It doesn't necessarily have to have a huge, long span, but when it works, it's terrific. So that's one of the hats you wear, and that requires you to really have done your research on what you're sending the photographer to shoot.

Now, my experience was always with film in the beginning. I started working at Life Magazine in the mid-sixties. I did graphic photography there, so everything was filmed.

So the next thing you have to be able to do is to go through the work and be able to-- Mr. Pollard, who was the head of Life, told me once, "When you're looking in among the rocks, there are always pearls. And when you see them, they'll jump out at you. So your next part is to begin to go through the film and look through those images that just make you stop and begin to think about, as you pull those up, how you make a story and that every story has a beginning, a middle, and an end.

And when you sent the photographer out, you give them your take on what you think this story is about.” The last line was, “I need this. And then, once you've got that done, then surprise me."

So you're always looking for that moment where you're surprised, because that's what will make readers stop and look at that picture and want to go back to it, and that, of course, is the beauty of still photography in that, when it's really great, it burns the image in your brain, and you do not forget it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, what does it mean when you're sending a photographer into harm's way? How do you cope with that?

Karen Mullarkey:

It is never easy. You only want to send people who are seasoned and smart and will know how to control their adrenaline and not take ridiculous risks, but there's no way you can guarantee anything in those kinds of situations. In some ways, you hold your breath.

I was really fortunate while at Newsweek, I had a couple of people kidnapped, but I never had anybody die and they were released. One was kidnapped on Shining Path, and those guys don't usually release anybody. And one was captured by Hezbollah, but they both got released.

So you worry about it all the time, and you monitor the situation carefully, and if you think this person is taking unnecessary risks and they've lost that part of the brain that would just say, "Gee, maybe this isn't a good idea." When they lose that, it's oftentimes when they get wounded and lose their life. There are a lot of examples of that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you think you would have become this national treasure of photography if you did not know how to type, take dictation, and make martinis?

Karen Mullarkey:

Never, never. Given how I started as the secretary to the director of photography at Life Magazine, I wasn't even the first secretary. I was the second secretary, the secretary's secretary in a way, but she couldn't type. She was a tiger-- British. No one got in his office without going past her.

However, she didn't type or take dictation, and when I got out of college, the only three questions that I was asked were, "How many words a minute do you type? How fast is your dictation? And do you make good coffee, honey?" I only knew how to make coffee. So I had to go to secretarial school for six weeks and just focus like a laser beam. And even then, I couldn't get a job.

Eventually, I got enough jobs that I wound up at Life Magazine, and then the hands of fate came and Mr. Pollard turned out to be my mentor, and he saw something in me I didn't see, but he took me under his wing and that's how I started editing.

One day, he said to me, "Are you happy?" And I said, "I could be happier." And he said, "Really, doing what?" And I truly wanted to pull those words back out of the air and I said, "Anything you take the time to teach me." And that's when he took me in his back room that had all the reject film, been through the picture collection, been everywhere, and that's when he told me to find a set number, "Find all the best, come back, and you're going to make a picture story,” and that's when he told me, "In the rocks, you'll find pearls and if they jump out and bite you, you'll know it and that's how I'll know if you've got an eye."

I passed that test a number of times, and then he gave me to different photographers. Gordon Parks was a teacher. Carl Mydans was a teacher, and sent me to the Life studio, and the boys taught me how to make a martini, which was extremely important, they said, for my education and it was! It was!

It was a different time, you know? And then, one day, he gave me to Ralph Morse, who was Mr. Astronaut, photograph of the monkeys up, did the famous shot of the original seven in their silver suits. So he said, "Ralph, I'm giving you a gift. I'm giving you the kid here as a Christmas present, and she can drive."

So down I went with him, down to Florida to Cape Canaveral, because I drive the film to Orlando. I learned how to run the teletype machine. I got the rooms and the cars, and I kept the wives separate from the mistresses they're hiding and I wound up shading on the VIP side. Eventually, by the time they were going to go to the moon, he had me produce the whole photography end of Life's coverage.

Guy Kawasaki:

You can correct me if I'm wrong, but you don't seem outraged that you were asked questions about typing, dictation, making martinis, nor were you referred to as a “gift” as if-- yeah, you're property.

Karen Mullarkey:

Property! No, I understand that. I understand that. You have to understand the time, and also I was brought up as a nice young girl, right? I realized what he meant. It was a gift, you know what I mean?

I realize that getting to work with Ralph, who was the most generous, lovely man and didn't have a sexist bone in his body, I understood it was a gift. I was getting Ralph. You want to know what the gift was. I was getting Ralph. I was getting to have that teacher.

That's the timeframe. We're talking 1964 is when I got out of college. This was common. You had two options: You could become a secretary or a stewardess, and I was too tall to be a stewardess, which is, of course, what I wanted to be. I was like dandelion fluff. I always say this.

Until I came across Mr. Pollard, and somehow, he saw that I was smarter than I thought I was. Then, I believed I was really pretty shy. And he did not have a sexist bone in his body.

As a matter of fact, he made it clear that...He called it college girls-- the young women who worked for Pollard-- they were off limits. There'd be no hanky-panky. Nobody better try anything or we report him, and I had a couple of events there that now would qualify for the Me-Too movement, and my answer was always the same, "Didn't you know Mr. Pollard's girls were off limits? Do you need me to tell him about this?" And boom, that was-

Guy Kawasaki:

That was it.

Karen Mullarkey:

Never happened again. That was it.

People ask me, "Did you watch Admin?" the TV show. And I always said, "No, I didn't watch that, because I lived it. I didn't have to watch it."

Guy Kawasaki:

That's how I feel about when people ask me, "Did you watch the Apple movie about Steve Jobs?" I don't-

Karen Mullarkey:

I don't need to!

Guy Kawasaki:

I was there. I don't need to, yeah.

Karen Mullarkey:

Would you like to see the lacerations on my back?

Guy Kawasaki:

You mentioned Jane Goodall earlier in the interview and I don't know if you realize this, but you have a very strong common point with Jane Goodall. She was my first guest on this podcast and the reason…

Karen Mullarkey:

Oh, wow.

Guy Kawasaki:

... that the Leakey’s hired her was because she had secretarial skills. That's how she got into the Leakey organization.

Karen Mullarkey:

I completely understand that, because in our timeframe, that was the entry level. I had learned, before I got to Pollard, actually, how to be... I wanted to be the best secretary they ever had.

At one point, I was working in Fortune ad sales before Mr. Pollard, and I basically told the two guys. Those guys all liked to go out. Those were ad salesmen. They would like to drink a lot. That was all part of that scene.

I basically said to them, "I'll do your business and you can get as drunk as you want, but I'm going to be the best secretary that you've ever had, but I need a raise every six months and the day you don't remember that is the day I...” And that's exactly what happened. They forgot one six months and I left, and that's one of the reasons I…

Guy Kawasaki:

No…

Karen Mullarkey:

Oh yeah, oh yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

Just like that?

Karen Mullarkey:

Well, I said to him, "You guys, did you think I was kidding?" And I had, by this time, made friends with a guy who was the head of the HR department at Life that was the first African American to have a big job there. They called him a vice president of HR and he actually sent me down to the picture collection, because he wanted me to gather some pictures. I believe it was about Dr. King, and I found the picture collection, and I just fell in love with it, and having put those pictures together, well, that's how he sent me to Pollard.

Mr. Pollard was looking for a second secretary at the time, which I was really good at, and that's how I got that opening.

Guy Kawasaki:

So…

Karen Mullarkey:

And then, two guys from Fortune said, "Wait, no, you can't." I said, "You gave me your word. You gave me your word, and you didn't keep it."

Guy Kawasaki:

Just for clarification, so you're saying that you left that position supporting the two salespeople because they didn't give you a raise and then you got to work for Richard Pollard?

Karen Mullarkey:

Yeah, in a roundabout way. I wound up needing a job. I think his name was Trent-- Mr. Trent. I'm searching for his name. He was the man who ran HR, and he had me do this project for him, and then, once I did that well, I could've been a floater or whatever, but I wasn't working for those two guys anymore, and then, the opening in Pollard's office came up, and he sent me on up.

Guy Kawasaki:

So looking back, what are the career lessons about your start at Life? What's the wisdom there?

Karen Mullarkey:

Oh, the answering machine is going… There's no whining. There's absolutely no whining. Oh, their answering machine is going. I'm sorry if that-

Guy Kawasaki:

That's okay.

Karen Mullarkey:

... if you hear that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Slice of real life.

Karen Mullarkey:

It's a slice of real life because I'm in someone else's house and I can't do anything about it.

So first thing I learned is there's no whining, and there is no job too small or there's no job that's really beneath you, and there's no job too small that you shouldn't just do it brilliantly and that you should always try to make it right the first time, and everybody makes mistakes, but you try really hard not to make the same one twice, and the other one is: ask questions.

If you're not sure what you've been asked to do, ask questions until you get it right, until you understand exactly, and be humble when you ask it. It's like, "I don't quite understand what you're asking me to do." A smile works so much better.

You have to jump ugliness later, but it's always better if you start out not on that foot, if you start out nice. You can always go to the other side, but you don't want to go there unless you really have to.

Guy Kawasaki:

There may be hundreds, hopefully even thousands, of millennials who just heard your advice, and their minds are doing backflips, because everything you've said is probably contrary to what they believe how the world should work.

Karen Mullarkey:

Well, that's not how the world works is the problem. I coach students one-on-one, and I always lay down a couple of ground rules. I say, "You don't have to come back if you don't want to, but these are the ground rules. There's no whining at all; can't bear it. Would prefer you didn't tell me that you're dumb and start out sentences with negatives.

Basically, I talk; you listen. Then, you talk; I listen, but I always get to talk first.

I've earned that right. When I was Mr. Pollard's secretary, I did not talk first. I listened. He talked first.

I never went in his office until he opened the sliding door. He'd move me around in this little area, and he'd open the door from the inside. I never would go in there until he’d done that and he was ready then to deal with me.

He got in at some wretchedly early hour and all the stuff he wanted me to write, and it would just be the name of a person on a piece of brown paper and four points, and I'd write the letter, and because I could take dictation, I sat in his office when he cut deals with the Associated Press, when he wrote contracts, when he did everything and I was the court reporter.

So I learned how to write a contract. I learned how to deal, and then when they would leave, he would say, "What do you think of that?" And I'd say, "I think you could've gotten more money out of Mr. Buell," who was the head of the Associated Press. And he'd say, "Really? What do you think I could've got?" "I think you could've gotten another $1,000." He said, "Well, try to get that."

So I would read back to the transcript to Mr. Buell, and I would just tack on $1,000, because he didn't like people swearing in front of me, but those guys all did. Everybody would drop the F-word, the F-bomb, constantly and I would take everything down and hand-draft it, and Pollard said, "Hal, I don't want you to use that language when Karen's in the room," and blah, blah, blah. Jesus Christ, whatever.

So I had it verbatim. So I would read it and he would say, "Are you sure?" I said, "Oh yeah. No, see, then you said da-da-da." And Mr. Pollard said, "I don't want you to use that word." "Then, you said ba-ba-ba. And then, you came to him and I tacked on the grand." And I would write down, and then he said, "Oh okay, fine, type it up." And then, I went in to Mr. Pollard and I said, "I got that $1,000."

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh my God.

Karen Mullarkey:

Bobbi Baker-Burrows, who was at that time Bobbi Baker, who went on to be the picture editor of Life, never left Life. She and I were the closest and best of friends. She was short and blonde. I was tall and thin and brunette. We were the Mutt and Jeff, and we got away with murder and Pollard adored us, but we worked so hard.

It was exciting. It was exciting. You were surrounded by smart, interesting people who had such phenomenal lives, and you just wanted to be a sponge and soak it up, ask questions.

So all these young students I deal with, they come in thinking you're going to do it their way. One of the lessons I teach them is: that is not how the world works, and that is not how you're going to be successful.

Once you get a lot of experience, well then, you can afford to be a little bit arrogant, but you better be able to back that up. Arrogance and stupidity are oftentimes together. That's a bad combination.

Guy Kawasaki:

It's an ironic combination.

Karen Mullarkey:

It's a nasty combination.

Guy Kawasaki:

One more Life question, which is you have to please tell the story of the picture of the Martin Luther King assassination.

Karen Mullarkey:

Oh, just sad story.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes.

Karen Mullarkey:

Well, I was still the second secretary, whatever, and that was 1968 and, I have to tell you, that was the worst year. I never went to bed that year, really. The only good thing that happened that year is that they went around the moon around Christmastime, Frank Borman. That was the one good event, but if you look at what happened in sixty-eight, it was mind-boggling.

So Dr. King is murdered in Memphis, and there was a young man named Joseph Louw, who was with the group that was traveling with Dr. King. As an intern, he was there and he was connected to the public broadcasting company. Something tells me he was here from South Africa. Something about him was also unique

Anyway, he is there when this catastrophic event occurs and he takes pictures, then he calls his boss at PBS and tells him what has transpired and what he has. That person knew Phil Kunhardt very well. Mr. Kunhardt was one of the assistant managing editors, and that name is fairly well-known now because I think it's his grandson who produces all these great coverage things, as his son did too, Peter.

So anyway, Phil gets this call and buys the film sight unseen, which was very common, and it's something you have to learn to do and have nerves of steel when you do it. I did it at Newsweek. It's a scary proposition.

So he bought it sight unseen. So the decision was that this kid was going to fly to Newark Airport and someone would meet him, and it was determined I would be that person. I didn't ask for it. I was picked, right? "Send her. Send Karen." And so I go to Newark Airport.

In those days, you could take a cab from New York to Newark, but you had to take a Jersey cab back. There was no round-tripping. So New York cabbies didn't like to even go there, because they were never going to get a fare back.

So I get a cab and I have a rolled-up Life magazine, and I'm told this is a young African-American guy named Joseph Louw, and I have to meet his plane, and I have to get him in a cab back to Life Magazine. Now, this is going to be somewhat in the middle of the night, right?

I'm not to walk in the building if I don't have the film on my person. So I go and I'm walking around with a rolled-up Life magazine. I have a driver who I tell him, if he will wait for me, I'll give him fifty bucks. They gave me enough money, and that was a lot of money in 1968, and I said, "Just don't leave. I don't want to be looking for a cab. I just want to come out and be with you. You're going to take me back." So I walk around and sure enough, he finds me, because I've got the Life magazine.

We exchange, and he's a nice young man and shell-shocked, right? Dr. King was a hero for him. He was everything. So I get him in the taxi, and we start to head back and I'm saying to him, and I meant this too, "You poor guy, what an awful experience, so stunning. Awful, awful. How are you doing? Where's the film?"

And then I keep talking and every other word I say to him, "And where's the film, Joe? Have you got the film?" "Oh yes," he goes, "I've got the film." I said, "Why don't you hand me the film? And that'll all be taken care of." He goes, "I have it, but I processed it, because I was afraid they might take the canister…might be stopped at the airport." And I said, "Well, you processed it. That's incredible. Where is it?" And he goes, "I taped it to my chest." I said, "Really?" What he had done is taken the manila envelope, the eight-by-ten envelope, and cut strips of the manila envelope, put each roll, each frame, not frame, one-through-whatever, in a sleeve of the manila envelope and had taped that to his chest, okay?

So it was like he was a walking contact sheet and I said, "Really, you did? Oh my God, how remarkably clever." And I start to undo the buttons on his shirt and I'm saying, "Show me. Show me how you did that. How smart of you! How incredible. That's incredible!" I'm taking his clothes off and the cab driver is panicking, because he thinks I'm about to do some other deed in the thing and he starts yelling, "Not in my cab." And I say to him, "I'm not going to do that. Just drive and I have fifty dollars for you."

So by the time I get Joe's shirt open, sure enough, it's all there and the great thing was he did not have any chest hair, because while we're talking, and I'm telling you, I am ripping each one of those off, and I'm saying, "Let's get this off your body, because you could be perspiring."

I'm gathering all of them, and now I have all of them in a bag and buttoning his shirt back up, and the whole time we're doing this, I'm saying to him, "I feel so terrible for you. Don't you worry. When you get to Life, we're going to take care of you. Everything's going to be taken care of. You're going to be okay. Everything's going to be fine," all on that line, and I meant it and gently rubbing his back and whatever while I'm, with my right hand, ripping everything off.

So we get to the building. I give the guy the fifty dollars. He can't believe what's just taken place in his cab, and we go into the building, and I take him up to the floor. I think it's the 29th floor of the Time-Life building, and we walk into Mr. Kunhardt's office, and I put Joe in front of me and behind him, I just hold up my thumb like, "I got it." I introduce and I say, "Mr. Kunhardt will take care of you now. I have something I have to do," which was I walked it down. I did not put it on the dumbwaiter. I walked it into the lab, and they made the contact sheet, and that's where that picture comes from of everybody pointing.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow, wow…

Karen Mullarkey:

And that's how that happened.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow.

Karen Mullarkey:

There's another part of that story, which involves Bill Eppridge, and so we're looking at the film after the contact sheets. This is a couple of days later, and Bill Eppridge is there, and we're looking at the contact sheets and he says to me, "You could tell he was an amateur." I said, "What do you mean?" He said, "He did not take the picture until they covered up Dr. King's head. He's an amateur—good, but an amateur." Now, this is April. I say to him, "Do you mean to tell me if Bobby Kennedy was shot in front of you, you would not instinctively try to help him?" because I knew how close he was to Bob Kennedy.

He was one of the photographers who covered Kennedy constantly, and they were good friends. And he looked at me and he said, "No, I would not, because my job is to take the picture. The editors here, their job is to edit. My job is not to edit the camera. My job is to record it." And then, we jumped to June and Bobby's shot, and Eppridge takes that extraordinary photograph of him on the floor of the kitchen.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow.

Karen Mullarkey:

And there were maybe four frames out of focus on that contact sheet. I learned a lesson, and the lesson was Eppridge was right. His job was to record the event and not to edit imaging, and that that would be done in the home office. And I learned a difference between a pro and an amateur.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let's shift gears again.

Karen Mullarkey:

Okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

Rolling Stone. So first question, is it accurate to say that you got your job at Rolling Stone because you cleaned up Annie Leibovitz's mess?

Karen Mullarkey:

No, no, I would not say that. I would not say that, because it wasn't Annie's mess. It was the photo department's mess. This was not her mess, truly, no.

What I encountered was a mess that was not of her making but which impacted her work, okay? Annie had her own faults in that timeframe, but sloppy with her stuff was not one of them. What I discovered was that somebody, who was her printer, had kept her negatives in a box that was under... There was a small little place to develop work prints, okay?

Her work was processed in a lab called Chong Lee in San Francisco. That's where her stuff was processed, her black and white, and then, the contacts would come, but they were not filed well. This was not Annie's fault. This was the fault of the photo department that had no idea how to be a photo department.

I had been trained someplace where I knew how negatives were numbered. It was a tight ship. When I came, when I was walking around to see everything, as I stumbled on this box that was under the sink where the water was running and I asked what was in the box.

The young man, who went on to be a fairly famous photographer, said to me, "Oh, they're Annie's negs." And I said, "Really, under the sink? And why are they there?" And he said, "Because it's so much easier to get to them." And I went into the photo department, and they had a fireproof five-drawer cabinet that had a combination and it was fireproof, and there were other file cabinets that weren't, but in the fireproof filing cabinet with the combination were headshots, one shots, from record companies, those 810 glossies. That's all that was in there.

Annie's stuff was in another cabinet and I just thought, "My God," right? And I had yet to actually meet her. She was on assignment in South Africa, doing our reports there for the last of the Mr. Olympian. So when I started, she wasn't there, but I took all those glossies, and I just threw them on the floor, and I put her stuff in the filing cabinet that was fireproof and I began to organize it, but it was not her fault that it wasn't organized.

It was the fact that inept people were in charge of the photo department, and it all started as, "Hey, it's fun. Let's go there and get a job and just play." I knew how to play, but I had been trained differently.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wasn't the proposal that you and Annie and, I don't know his name, were going to come in some weekend and clean it up?

Karen Mullarkey:

Oh, well, that was before. When I went there and I interviewed on my way up north, I had been working at Psychology Today in Southern California in Del Mar and had been living the surfer-hippie life. And then, they decided to go back to New York, and we chose not to go. Our department chose not to go.

I needed a job and I had a '55 VW, and I had a boyfriend who lived up in Garberville and he was an artist. And so, I was on my way driving up there. I went as far as San Francisco. I stayed with my cousins, and I stopped in to see if they might have a job.

That's exactly how you got a job there. "And what do you do?" "I'm a picture editor." "Well, how do we know?" And I said, "Why don't you bring me a contact sheet, a loop, and a grease pencil?" And they did and I marked it up, and I said, "Well, look, I got to go. I have to get on the road, but I'll stop in on my way back."

I stopped in on my way back, and the person who had been in the art department said to me, "Well, you really do know how to edit." I said, "Oh yeah," and he goes, "Well, we could use you." I said, "Well, I'm not so..." And that's when I walked around and saw what a mess it was, but didn't take the job.

I went home, and I got a phone call from Jann Wenner down in San Diego when I'm living in this little shack for seventy-five bucks and says to me, "Listen, I have a great idea," because I had said, "Well, this place is a catastrophe," when I was up there, "What a mess!" So he called basically and said, "I have an idea. Why don't you come up here and, Annie, you, and I will work for the weekend, and we'll put everything in order?"

My response was, "Well, that's an option," I said, "but here's another one, which I think would have the exact same results. We could put three elephants in there, close the door for the weekend, and then we'd come back and the same amount of stuff would be on the floor," because I didn't care. I was producing commercial work for the guys from Magnum, because they all wanted to shoot in San Diego in the winter. It was always great. When I'd been working for Psychology Today, I would find people off the street to be the models for the pictures.

I was really good at producing stuff. So I thought, "Well, I don't want to." And I knew about him, and so I thought, and I said to him, "No, here's the thing. I couldn't possibly." I said, "I've got all this experience. I'd be really good but I’d have to do it my way, but that's okay if you don't want to. It's fine." And then, he called back in a couple of days and said, "Oh okay." And that's how it started, but I really did not meet Annie until after I was working there and she got back from South Africa.

When she was down there, I kept hoping against all hope that she would photograph Arnold like a piece of meat. So I'd see the calf, and a picture of that and this, just pieces of his body besides the obvious portraits and stuff she would do. So when the film came in and it was being processed, and I got to look at it, I was thrilled. I did not want to call her and introduce myself. She knew that I had been hired, and she knew my background was Life. So she was a little anxious about me.

I was thoroughly interested about her, because I thought she was brilliant and I knew she could be difficult. So we were both a little wary of each other in the beginning, but we worked that out.

It took one little encounter, and then we were the same height. I was six feet in those days, so was she, and she was nervous because I had worked with all those Life photographers and I had, by that time, learned how to speak up. So we had one little moment, and then I, basically, told her what I thought I could offer her and that was that I could see that she didn't understand lighting and things like that.

She didn't! She was instinctual. Her instinct is extraordinary. Technically, at that time of her young career, that was nothing that she had mastered, how to set up lights. Some people understand all the technical stuff, and they shoot a perfectly lit, boring picture.

Annie had the other skillset which, of course, makes her so remarkable is her intuition of when to push the button. It was spot-on, but she didn't understand how to set up lights in the studio situation. She hadn't been trained in that.

So I told her I would hire assistants for that and I said to her, "You can eat them for lunch. They're a dime a dozen, but you will learn. That's what I can do for you, and I will try to edit well, and you know what you're going to do for me?" And she said, "What?" And I said, "You're going to teach me to see better, and I think it's a perfect give-and-take relationship. That's what you will give me, and this is what I will give you. And how could we go wrong? Now, think about it. Don't say anything," because we'd been a little testy with each other.

I said, "Think about it, and then come back and tell me what you think." She came back and said, "I think it's a great idea." I said, "Should we shake on it?" She said, "Yeah." That's the last argument we ever had.

Guy Kawasaki:

And-

Karen Mullarkey:

Ever.

Guy Kawasaki:

How did she teach you to see?

Karen Mullarkey:

Oh, because she hated to stand where anybody else was. No one else shot Dan Rather sitting on the rolled-up carpet when Nixon was being taken off. Nobody shot that. She did. The way she understood people, her intuition, was phenomenal. Plus, she'd studied art.

Initially, when she went to the art institute, it wasn't to be a photographer. It was to be a painter. She had great painterly instincts. I would look at her work and I would just think, "God, nobody..." She just hated standing where anybody else was. That's the best way I can put it.

So I saw that she had an offbeat way of shooting that was different from how news people would shoot, you know what I mean? And that certain kinds of pictures of hers might not have made it in the Life Magazine I grew up with, right? Then, later, they would

So I saw that about her work. It was wonderful to look at her pictures, and I would be able to tell her. She'd be on assignment somewhere, and I'd look at this and I'd say, "I think the lead singer used to be with the lead guitarist, but I think she's shtupping the drummer," something like that, and she would say to me, "Shoot, you're right,” and I would say, "I think it's time to put color in the camera."

We did not shoot that much. We did not run that much color in those days. We were toilet paper basically, newsprint. So it was important to shoot for covers and stuff, to try to shoot in pastel colors, because if it was too saturated, it would just soak in and not be good. I still say that. She has her intuitive sense of what makes a composition spectacular, really.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do-

Karen Mullarkey:

It was a great learning experience. We had a lot of fun. We behaved badly. We did, oh God. It was rock-and-roll. It was the seventies. Everything you heard about that period is true.

Guy Kawasaki:

Did you have a role-

Karen Mullarkey:

Probably underplayed, probably underplayed.

Guy Kawasaki:

Did you have a role in the John Lennon/Yoko Ono shot?

Karen Mullarkey:

No, the one where he's naked?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes.

Karen Mullarkey:

No, I had left the magazine by then and as a matter of fact, I have that as a present from her. I have four of five of the original prints she made.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow.

Karen Mullarkey:

Number four of five, and it's autographed to me with all her love, and she signed it Anna-Lou, which is her real name.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow.

Karen Mullarkey:

Her real name is Anna-Lou Leibovitz.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, next Rolling Stone question. I think that using the power of social media and the internet today, we can find either the ladies or the children, or grandchildren of the ladies, who were at the fence that Richard Avedon took the pictures of.

Karen Mullarkey:

Do you think you could?

Guy Kawasaki:

I think so. So I want you to tell that. That is a great story. Holy cow!

Karen Mullarkey:

I know. So Dick Avedon and Jann Wenner got together and came up with this idea, which was to be done for the bicentennial in 1976, and it was called The Family. I'm not privy to know whether it was Jann's idea. He took it to Dick Avedon, or whether Dick Avedon had the idea and told Jann about it. That I do not know, but I do know, between the two of them, they came up with this brilliant idea.

Avedon was going to travel everywhere and photograph the movers and shakers in his 810 camera, and wonderful pictures. The ties are phenomenal. Anyway, once this is done, he is coming to San Francisco to work on the layout, and he didn't know us and he wanted, maybe, Bea to help him, Bea Feitler, who was a great, talented art director in New York, because he didn't know us, but when he got there and he met Roger Black, he was like, "Oh, this is wonderful,” and I was really nervous about meeting him, thinking, "I'm this rock-and-roll princess," whatever, and I was so sure he was going to be, "I'm Dick Avedon and you're not."

That's my line about why about a national treasure makes me nervous, because what I learned from Dick Avedon, who is a national treasure, was that he did not do, "I'm Dick Avedon and you're not," right? A lot of the really great ones that I knew never did that.

People who have a lot of money don't talk about it-- who were brought up with a lot of money. Old money never talks about money. We get to know each other, and we have this funny little encounter, and I have him in my '58 VW.

He thinks I'm going to kill him, because he's never been in a car that has nothing. It had nothing. It had a horn in the middle, and it had an Allen wrench on the bottom. You needed to turn that so you'd have gas.

After we spent some time together, I planned a luncheon in Mill Valley. My housemate was a photographer, a tabletop photographer, really good food photographer, well-known at that time, and so, I had a luncheon and I had salmon. It was out of a deck. It was beautiful in Mill Valley. It was a lovely luncheon, and a couple of the guests that were from the art department, and one of them was the art director, Susan Hindle, who was Roger's assistant.

She and I used to like to take mushrooms, okay? And so, after lunch, and we decide we know about the fence, and so we think it'll be fun. “Let's drive out there.” Bartone is going to drive his Mercedes or whatever, and we're all going to go in that car. And Susie and I thought, "Well, for dessert, let's have some mushrooms."

So we get in and we all drive out to the thing-- the fence, and Avedon sees the fence, and this was the crystal fence that came out of the Pacific Ocean and went directly east through Marin County, the west part of Marin, which was unpopulated and quite beautiful, and went all the way over to Highway 101, okay? It was spectacular, and we went to the far western end of it. It was getting close to sunset, and Avedon saw it and went crazy and said he couldn't believe that Vogue did not have him come and do a fashion shoot against the fence, "How is that possible?"

He was just railing on about it, and this was the worst thing. He couldn't believe that they were that stupid. So we're standing there and Bartone is with us, Laurence Bartone, my housemate, these women are standing by the face, and they've got one of those little point-and-shoot cameras and they said, "Would somebody take our picture in front of the fence?" And Avedon goes, "I'll do that, I'll do that." So he takes the point-and-shoot. Whenever he was shooting, he'd put his glasses up on his forehead, up high, right?

Of course, he's used to shooting a large-format camera, where everything is upside down and backwards on the glass plate or something. So he takes this camera, and he realizes he has no idea how to use it, and he turns to Bartone and goes, "How does this work? How does this work?" So Bartone shows him, "This is how it works. This is how it works." We don't use his name and he goes over, and these women have half a roll of film, and he just poses them constantly, different ways, and shoots them, shoots the shit out of it, just shoots everything that, in his mind, he would've liked to have done.

He was doing horizontals and verticals and this, and coming in tight and back. When it's done, he hands them back the camera and they're just like, "Wow." They're so excited. "No, no, I'll take one more,” and they hand them back the camera and off they go, and they never know they were photographed by Richard Avedon.

Guy Kawasaki:

I think we should try to find those ladies!

Karen Mullarkey:

And then, of course, we take the last helicopter ride, he and I. There was room for just two and we're taking that, and he is just going crazy. The sun is setting. I am peaking on mushrooms. This'll tell you about Rolling Stone, and he's going, "Man, the light is amazing." I'm going, "Amazing! You don't know how amazing this light is, oh my God!"

But that was a classic Rolling Stone story. That's what it was like in the lifestyle, and that's what I say.

Somebody once told me that they were going to do a story on Annie during our period and I called her up. This was after I'd left there and I said, "Annie, they want me to talk about that whole period and what went on there." She'd cleaned up and all that. I said, "I don't know if they want to talk about cocaine." And she said, "I've already talked about it, so there's no big deal." I said, "Well, yeah, but you've got kids." "No, no, go right ahead."

I say to her on the phone, she's from The Boston Globe or someplace, and I say, "What year were you born?" And she goes, "seventy-four," or something. I said, "Oh." Seventy-five and I'm thinking, "Well, in that timeframe," I joined the Rolling Stone in seventy-four, "everybody was doing cocaine." The streets were paved with it. You name the industry. They had sugar bowls of it, right? It's just what was going on then.

I said, "If I were to try to tell you about this time, you know what it reminds me of is my parents lived through the Depression, and they used to tell me stories about how desperate times were then and how impossible it was to find work and how food was a shortage, and this and that, and during the war, when I was born and food shortage, and I would listen, but since I never experienced it, I couldn't really understand it.

That would be like my talking to you about this period. You would hear the stories, but unless you lived in that timeframe, you wouldn't really be able to understand it."

Cocaine is one of those drugs that makes you incredibly stupid, in which you think you could do it in front of a cop and it would be just fine, and we used to think it wasn't habit-forming. We were in another planet in those days, and some people didn't make it out and some of us did. We look at that now and we go, "It wasn't because we were smart. It's just because we were lucky."

Guy Kawasaki:

With hindsight, you don't think that the drugs enhanced creativity in photography?

Karen Mullarkey:

Well, no, I think that's BS, but at the time, I believed it did, right? At the time, that was one of the reasons that we thought we were so fabulous, but we had a lot of talented people there. We were just all on the same crazy highway together.

Now, if I were to look at that, would I want to go... You know what I say about my life? I say I never have to say, "Gee, I wish I had." And I think if you can live to be what I'm going to be, seventy-eight, and you don't have, “Gee, I wish I had’s,” I think you've lived a good life.

Guy Kawasaki:

Amen, amen. So now, let's go to Newsweek.

Karen Mullarkey:

Great job.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, tell me. So far, you've had a few great stories for every place. What's your great story about Newsweek?

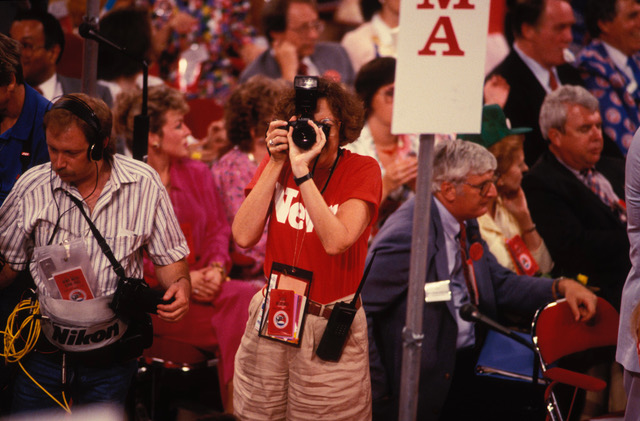

Karen Mullarkey:

Boy, I'll have to say that, first of all, I was the first woman to ever be hired to do that job at any of the news magazines, so I broke the glass ceiling, and they came out and recruited me. At that point, I was working at New York Magazine, and I had done rock-and-roll. I was doing fashion in those days with Anna Wintour. Anna was the fashion editor at New York Magazine.

So when they went to interview me in many different, I went through many interviews, I knew a bit about it. I'd done my homework and I was nervous about taking the job so I asked for a couple of things, because I knew I'd be the first woman, and they were bringing me in from the outside and that had never been done. It was always one of those things.

Through the ranks, you got the job. You'd had a background working for the wires, and it was a man-only game. No one else but men had ever won any of those departments, and that's at US News and that's at Time and that's at Newsweek.

So I wanted and understood that-- and this I say as a joke, but it was kind of true-- I wanted a public coronation. I wanted a great photograph of it. I actually have a great photograph of it.

So I said that to Mr. Smith, Rick Smith, who hired me. He was the editor-in-chief, and Newsweek was part of The Washington Post so all of those guys reported to Katharine Graham, who had broken many a glass ceiling. So basically, I said the reason was I knew the culture there had been to treat the photography department badly and to humiliate those people and to consider them third-class citizens, not even second class.

This is what I asked for at the last meeting we had and I said, "But I want them to see that I answer only to you, and that includes the assistant managing editors. I only will come there if it's understood I only answer to you. And that is really important, and that I will meet with all the senior editors and everybody else, and I will tell them how excited I am to have the job, and if they have any problem with anybody who works for me—” at this point, the lab would've worked for me.

Plus, people overseas were working for me, and that would've been the number of people under me. I said, "And I will go to every one of them and tell them, if they have a problem, they must come and tell me or call me, and I'll come down and well work it out, and I'll solve the problem. But then, if they pick on anybody who works for me, I will assume they will have done it to me, and that would be a really bad idea, because I will wait like a snake in the grass and I will nail them, and I will do it in front of you and you will let me because you know what? I'll only have to ever do it once and never again."

I said, "And I'm going to work." And I wanted to get Roger to come there to be the design director, and I got my people in the art department, didn't take me long to make that happen. So we were a cohesive unit, and that's exactly the conversation I had with everybody. I really only had to do it once, never had to do it again.

That way, these people that came under me were shell-shocked. They were used to being humiliated and all this stuff, and that stopped, and I basically put each of them in charge of certain things.

One of the fellows who was going to work for me really wanted the job and was thinking he would quit, and I knew him from before. I said, "Give me six weeks. And if, at the end of those six weeks, you weren't happier than you've ever been, I will use every key on my keychain to get you a job, but I think you'll find this is-- nobody downstairs is going to." I won't use the F-word, but that's what I said. "Nobody's going to do that, nobody, because they're going to have to go through me, and that is never going to happen."

So about a month, this person came in and said, "You were right." I said, "You got it." We had the most cohesive team, to the point that Mrs. Graham came to see me one day and closed the door and literally, I don't make this up, she had almost tears in her eyes and said, "No one's been able to do this. The photo department, the art department, you're all one. You did this." And I said, "I was given the opportunity." But by that time, I'd learned so much, and all along, when I was at New York Magazine, I was starting out young photographers.

Between Rolling Stone and New York Magazine, there was a rebirth of look, and that's when I gave Herb Ritts' first work. That's when I found Herb Ritts. Because I was mentored at Life, all I could think about was passing that along. So all through Rolling Stone, in some ways, I might have been-- Annie mentored me; I mentored her, and there were other photographers out there that I gave work to early, Roger Ressmeyer, all sorts of people who were doing rock-and-roll at that time, and Roger didn't have his name on his contact sheets. I wouldn't give him work until he put his name on everything.

I was just paying it back. And finding young talent was just fantastic, wonderful, wonderful and to then see them. So now, all these people, I started giving Joe his first work. I look upon that. We all stayed friends. Doug Menuez-- I gave Doug some of his first work.

Guy Kawasaki:

Really?

Karen Mullarkey:

He was working for a place called Picture Group. Now, he'll tell you a funny story about my making him go get me bourbon before I'd look at his content.

I said, "Do you mean to tell me I've come all the way up to Providence," I'd say to Donna, "and you don't have any Jack Daniels for me? Are you crazy?!" And so, I looked over at Doug and I said, "Young man, I know you want me to look at your portfolio. You need to go get me a bottle of Jack Daniels." It was after-hours. It was Providence.

He went to a bar and paid extra to the barman to give him the bottle of Jack Daniels, and he brought it back and put it on the desk, and I thought, "This is one resourceful guy,” and that's how Doug and I started.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh my God. Well, now, I have to ask.

Karen Mullarkey:

So maybe all of that makes me a national treasure-

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm-

Karen Mullarkey:

... because I was willing to break all the rules.

Guy Kawasaki:

I'm coming to that conclusion. You got to tell us at least one Anna Wintour story now.

Karen Mullarkey:

Oh, Lord. Actually, Jerry Oppenheimer wrote about this situation. It's in his book about Anna.

She had perfected the art of being a brat to a fine art. Nothing was ever good enough, and she used to come back and just be nasty.

Now, this is at New York Magazine, and to get to the art department, it was laid out in a big L-shape, okay? So the long part of the L was where the newsroom was, where everybody sat and there was a center aisle, and then you got to where the editor's office was and you took a right, ducked to the right, and you'd walk past Nick Pileggi and all these great people, and that would end in the art department.

So there was the design, some layout work, and then you'd come in and there we were, and Roger had his table and I'm next to him. It was just ten of us in there, I think, if that. And she would come in and just be horrifically rude to people who worked for me, and I thought, "Well, we have to stop this right away, right away."

So I went up to her and I said, "Can you come with me just a second? I have something I want to say to you, but I'd like to do it just outside the threshold here. Come across." So she stepped over into the other area and I said to her, "Listen, I want to tell you something. I don't care how you behave on this side of the room. It's none of my business and people put up with it. Let them, but the minute you cross this line here, you come into this area, you have to leave that package outside, because now you're doing it to me and I won't put up with it."

Now, in those days, I'm still six feet. I'm in cowboy boots and jeans, and one of my Nudie...Nudie made the best cowgirl shirts, and it was light blue and had leather on it, and I'm just this big, broad kind of person and I just thought, "I'm not going to put up with it." And I said to her, "Listen, I know that you're really talented and you're really good, and I'm looking forward to working with you, but this is the terms. Honor these terms, but I don't care how rude you are on the other side. You cannot bring that in here, or you will come up against me and that won't be good. That'll be bad."

So she goes back and I said, "You should go check me out." So this is after Rolling Stone, right? So she goes and she makes a couple of phone calls and they say to her, and this is Jerry Oppenheimer's book, "Don't fuck with her. She is a six-foot cowgirl and she'll hurt you." After that, we never had a problem.

I used to tease her, because it made her crazy. Her father was British, but her mother was an American. And so, I used to say to her, "God, your mother's an American." I said, "You know, my mother is Jewish, so I'm Jewish. I don't know how to break it to you. You're an American. Your mother's American." She hated that. Oh my God, but I learned a lot from her.

Guy Kawasaki:

What?

Karen Mullarkey:

I'll tell you this.

Guy Kawasaki:

What?

Karen Mullarkey:

Oh, she had a great sense of style, and she had great, brilliant ideas, really, really good ideas. She got Schnabel. She knew all the young artists, Katz and Schnabel and all of them, and they would put these backdrops together for her and everything else. She knew clothes and she understood what looked great, and she was smart as a whip-- nasty, but smart.

You got to be a sponge. When you see talent like that, what you want to do is watch carefully and soak up as much of it as you can and adapt it to what you can do with it. All I wanted her to do was not be rude.

Guy Kawasaki:

It seems that you have a great deal of data to which to apply to the question I'm now going to ask you, which is, having worked with Annie Leibovitz, Anna Wintour, Dick Avedon, do you think that their, shall I say, harshness caused them to be great or that, because they were great, they could get away with it?

Karen Mullarkey:

First of all, I think they were perfectionists, okay? Talented people have trouble tolerating. They don't suffer fools well and that's okay. I don't think they were harsh to start, and I'm not sure I would use the word harsh. I think they were perfectionists, and they had a real sense of what would work.

I would tell you, Annie would shoot until she got it right. Dick Avedon, the same thing. Anna left nothing to chance. She had done her homework. She had really thought about the clothes.

When we would go out on a shoot, there was so many options and so much. For her, it was like a canvas, and she had a variety of paints to use. She could, at last second, run over and find just the right piece of an accessory that would change everything.

So I look upon them as highly talented, very creative people who had a very clear vision, and I think that's what you find in great photographers. I think Herb Ritts had a very clear vision.

One of the reasons, when I got to Newsweek, that I was allowed, I asked to be able to steal one photographer from Time. I took Arthur Grace for a reason because, like Annie, he hated to stand where anybody else was and he took off-beat pictures.

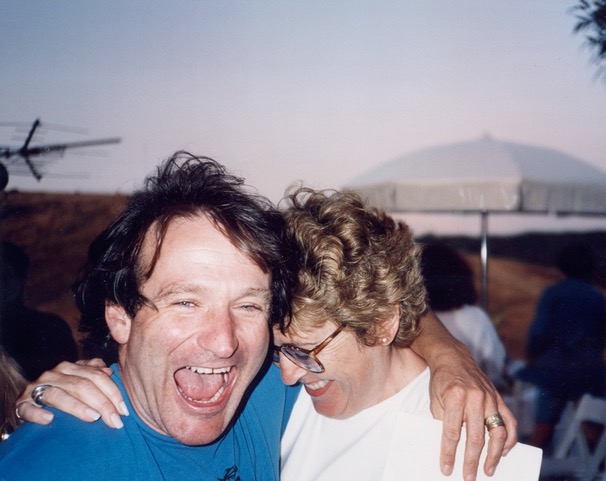

So when I had the assignment to do Robin Williams, I sent Arthur, because A) he used to do standup when he first got out of the Marines, and he was fast and smart. I thought, "This was the marriage to make,” and it was a marriage that eventually the three of us became friends for nineteen years, which rarely happens, but Arthur was the perfect marriage to make.

Arthur has a very defined sense of how he sees the world, and I am telling you that the great ones, that's what they've got, the clear vision and they are not interested in compromise. I think that is true of all kinds of talented people.

Guy Kawasaki:

Steve Jobs.

Karen Mullarkey:

I was just thinking of Steve Jobs. He knew exactly what he wanted, and he was not willing to compromise, but he-

Guy Kawasaki:

No kidding…

Karen Mullarkey:

Right?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah, absolutely.

Karen Mullarkey:

He could be a bully, but if you stood up to him, then he was interested. That is why it worked with Anna. She could be a bully, but I stood up to that. So what was the point? I called her on it, then it was not worth it anymore, didn't need to, didn't need to.

A lot of times, people who are like that also have a lot of insecurity. That kind of behavior just masks a lot of doubt, inner doubt.

Guy Kawasaki:

I think that that kind of behavior is the easy part. It's the perfectionist/genius part that's the hard part.

Karen Mullarkey:

It is, it is, it is. I agree, but there's a certain part of you that has to accept that that's what that person has, and what a gift, but you get that gift and you lose other things. You can't have it all.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, so last big topic. Let's say I'm an amateur photographer, wannabe photographer, wannabe professional photographer. How do you take a great picture? Is it the equipment? What is it?

If you're talking to a group of wannabe photographers and you say, "Okay, so I've worked with all the best. This is what you need to do to be a great photographer."

Karen Mullarkey:

All right, I'm going to tell you what I tell my students. How about that? Because I coach now at The City University of New York in the photography department and also video students, who are graduate students. So I tell them this, that there are two parallel paths. The first one that you need to do is master all the tools. You need to walk around with that camera in your hand so it feels like it's your hand. You need to know how to not have it on auto-focus. You need to learn how to do that yourself.

You need to learn how to read light with your eye. You need to become technically proficient so that it is ingrained in your brain and it's automatic. The auto-focus thing is in your brain, right? So you don't have to worry about your equipment. You need to master that.

The parallel path to that is learning composition and realizing that you want to take pictures that are your pictures, not somebody else's, that are unique to you and your vision. Everybody can look at the same thing but see it slightly different, and where is your sense of humor?

If you have all the technical skillset, then it's not going to impede your ability to-- I have a theory about the third eye, which I believe creative people have. This might seem like a little far field, but I'm not.

I used to gallop. I used to love to ride, and I even was crazy enough to gallop bareback, but what I learned was that, if the horse and I are one, you're just moving perfectly. If you're rowing, if you're in a scull and there are eight of you, if your oars aren't all going in the water at the same time and coming out at the exact same time, you're not going to make any progress.

So I used to weave rugs and stuff and one day, I'm working on the loom, and suddenly I'm looking down at my hand and I'm saying to myself, "Stay out of the way. Just get out of the way. They seem to know what they're doing." That is that third eye that creative people have and if you can allow yourself to find that rhythm, and if you've got all the technical skills, you don't have to worry about stuff.

Now, all you're thinking about is walking around and looking at an object from many different points of view, and you suddenly are trying to find out, “What is Guy Kawasaki's point of view. What makes this picture intriguing? What does he find funny? What does he find absurd in this world? What is it that makes him want to push the button on the camera?” Once, not 45,000 times, which is, of course, the problem with digital, because they can shoot 1,000 and they're not paying attention.

That's also the great thing. If you're pushing the button all the time, the picture's in the middle and over-shooting's like overeating, and these are all true. So what I would say to you, I would say, "Guy, what do you see that is unique to you, that brings all of your life experiences into how you view the world?"

In your earlier stages, I would insist that you go out and do that. Oftentimes, I make students do a five-block radius of where they live and pretend I'm from outer space, and I don't know what Astoria is or I don't know, and so you need to show me what makes that part of your world interesting.

Guy Kawasaki:

Great.

Karen Mullarkey:

Who are the people who live there? So that's the advice.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you think digital photography is a positive or negative?

Karen Mullarkey:

I grew up on film, okay? I grew up with people who did not see their work until it was over, until it was processed. They were not bobbing like little ducks, looking down all the time, and every time you bob down and look, you have lost your connection, and you have to refocus your brain, let alone your eye. So I had a student the first semester I was teaching, and I made him tape over the back of the camera. I thought he was going to have a breakdown. He really did.

He ran to the head of department and said, "She's made me cover up the back of the camera." The head of department was laughing. He thought it was really funny and he said to me, "Oh, you scared the crap out of him." I said, "Good. Fear is a wonderful motivator,” and he's laughing and I said, "You know why you're laughing so hard?" And he goes, "Why?" And I said, "Because I'm not doing it to you,” and he laughed and said, "You're right."

Excuse me, I have a frog in my throat.

I think digital has many things about it in this regard, okay? However, if you're not shooting Leica, digital Leica, you have a problem, because first of all, it's trained for center focus and the world is not center-focused. That's why I prefer Leica. That's why the greats always shot with a Leica and you get to take too many pictures, and you get to look all the time.

Then, here's the worst part. You erase your mistakes, which is a catastrophe. When you're shooting film and you made a mistake, you had to look at it and you had to say to yourself, "That was expensive and I would rather not do that again, so what did I get wrong here?"

One of my students now is shooting film this summer and we were talking, and she said, "Oh my God, I did such a terrible job." I said, "Did you look carefully at what you did wrong?" And she said, "Yeah,” and I said, "Are you going to go out and do it again?" "Oh yeah, I'm going to go out and shoot film until I get it right."

Think about this. All those guys who shot in Vietnam, unless you were a wire guy, Larry Burrows, they never saw their film. It was shipped unprocessed. They never saw anything unless it was published, and when they would come in for home leave, they would get to look at the outtakes. That means you think before you push the button and that, I believe with digital thinking, has been removed.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay.

Karen Mullarkey:

So that's my problem with it, and that's because I'm old-fashioned.

Guy Kawasaki:

Backing up thirty seconds here, explain to me. You said Leica’s are not center-focused, but everything else is. What do you mean by that?

Karen Mullarkey:

Well, in other words, if you have one of those little aperture things that's a circle, don't ask me technical shit, please, but anyway that is automatically-- and if you look at how a digital camera is, it tends to want to focus on the center of the picture.

The beauty of a Leica is it sweeps across, right? The shutter moves differently. It moves from right to left.

Guy Kawasaki:

Leica digital-

Karen Mullarkey:

Yeah, and-

Guy Kawasaki:

... or Leica film?

Karen Mullarkey:

Well, Leica film, right. That's why all of them, Eisenstaedt, every one of them, Bresson, everyone, wanted to shoot Leica.

First of all, the glass was phenomenal, the lens, but you had to compose the picture. I make my students walk around with the camera now and I say to them, "You are carrying a picture frame. So when you're going to take a picture, would you want to hang that picture on the wall? And by the way, you can hang pictures vertically, but I want you to walk around and not necessarily shoot right away. I want you to walk around and carry the camera as if you were carrying a picture frame. So as you're beginning to put your composition together, you will know when is the right time to touch the button."

Most people who have digital don't think about that, because they have 1,000 little opportunities on that little card. I just think it's lazy. I think it can make you lazy.

Guy Kawasaki:

I love that we're having birds in our podcast too, but-

Karen Mullarkey:

I was sitting here in the top of the trees and what you're listening to are cardinals.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's very touching. Okay, so my last question. Well, I don't know what your relationship was with your family, or your mother or father, but let's say that you decided you wanted a portrait of your mother or your father or your sibling or someone you loved, right? And any photographer, dead or alive, you could say is going to take this picture. Who would you pick?

Karen Mullarkey:

Wow. That's an incredible question. A couple of names came to mind. I think I'd have Cartier-Bresson take that picture because he had a great line about portraiture. He said, "Portraiture is the most difficult thing to do because you need to get between the subject's shirt and their skin," and that people have the wrinkles they have earned. He took wonderful pictures for that, one of which was Colette looking so dissipated, it's phenomenal.

But they were such honest pictures and they would be environment portraits, which I think I would prefer them to studio shot, and they would be in black and white, which I like the most, and it'd be very classic. Now, if I had said Avedon, I know that would've been caught in that 810 framing. If I'd said Annie, it would've been in color. If I'd said Arthur, who was one of my favorite photographers, Arthur Grace, it would've had more humor maybe, but I would go for Cartier-Bresson, thank you very much.

Guy Kawasaki:

Really?

Karen Mullarkey:

Yeah, I would. You should look at his little video. There's a video about him called The Decisive Moments, about 15 minutes. It was done with ICP and Scholastic. It's one of the most brilliant things on photography ever made. I make my students watch it first before they meet with me, because he's so much smarter than I am and I steal his lines all the time.

Guy Kawasaki:

And all he needed was a thirty-five-millimeter lens, right?

Karen Mullarkey:

That was it-- a Leica.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Karen Mullarkey:

That was it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Of course, now a lot of people listening to the podcast are going to go out and buy a Leica, and they're still going to have shit photos, though.

Karen Mullarkey:

Well, but that's because they won't take the time to walk around with it like a picture frame and think about... He said to Robert Capa when they put together Magnum, he said, "I am not a photo journalist." He said, "I am a surrealist," because he was a painter at first. "I am a surrealist,” and Capa said to him, "Don't tell them that. Tell them you're a photojournalist and shoot like a surrealist."

So if you look at his pictures, many of them are classic that way, but that picture that he will make that you will see is perfect from edge to edge, top to bottom. It's un-croppable.

Guy Kawasaki:

Karen, you truly are a national treasure. I wish you could bottle up all this wisdom, oh my God.

Karen Mullarkey:

I should write a book. I should write a book.

Guy Kawasaki:

No, no, don't write a book. Writing a book is too nineteenth century. It-

Karen Mullarkey:

Oh okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

There are better ways to spread your wisdom than writing a book that, the moment you write it, is out of date and most people won't read it cover to cover.

Karen Mullarkey:

Everyone's been after me to write a book and I try, and I can't spell. That's just awful. I can't add and I can't spell. I am an idiot savant on many levels. There are a couple of things I do really, really well.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well-

Karen Mullarkey:

I haven't balanced a checkbook in forty years. I just round it up.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, you're either overdrawn or not. That's all you really need to know, but-

Karen Mullarkey:

No, I don't care, I don't care, I don't care.

Guy Kawasaki:

To the people who say you really ought to write a book, just say, "Give me a two-million-dollar advance and I will," and then that'll shut them up. That's how you can tell who's really serious.

Karen Mullarkey:

I'll quote you on that.

Guy Kawasaki:

You can. Feel free.

Karen Mullarkey:

“My agent said you have to give me a two-million-dollar-advance.”

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh my God, this has been utterly fantastic. Thank you so much for doing this, taking time out of your sabbatical/vacation/escape.

Karen Mullarkey:

My escape. This is my place I come and escape here once a year for a month.

Guy Kawasaki:

Thank you.

Karen Mullarkey:

I do nothing except listen to birds and the sound of the water lapping on the bottom of the cliff here where I'm situated above in a log cabin.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh my. Well, you have great cellphone reception in that log cabin. That's great. Better than I have in Menlo Park in Palo Alto, California.

Karen Mullarkey:

That's because the couple that own this hill is a computer wizard. So he just put in a new Wi-Fi system that-

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, great.

Karen Mullarkey:

... is apparently quite remarkable.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay, Karen. Thank you so much.

Karen Mullarkey:

Thank you, Guy. Thank you so much.

Guy Kawasaki:

You are such a pleasure.

Karen Mullarkey:

I was nervous about doing this.

Guy Kawasaki:

Why?

Karen Mullarkey:

Well, I just was, but you made it very easy and I thank you.

Guy Kawasaki:

Well, now you and Jane Goodall are the two most famous secretaries that I know.

Karen Mullarkey:

What wonderful company to be in!

Guy Kawasaki:

No kidding!

Karen Mullarkey:

Wow.

Guy Kawasaki:

It doesn't get better than that!

Karen Mullarkey:

Wow. It does not get better than that!

Guy Kawasaki:

Bye.

DA provocateur: “Yesterday, I was feeling completely down in the dumps. Can we undo the systemic injustices upon which this country was founded? Well, Jamia Wilson fired me up and activated my true inner activist self. I could listen to her all day. Guy, thanks for the platform and for the provocative questions."

You are welcome! Keep those reviews and comments coming. Go to the Apple Podcast app and enter a review, please.

I hope that you found this episode of Karen Mullarkey as wild and inspiring as I did. It was utterly fantastic to hear her stories about the legends in photography, news, and fashion. I second the motion that Karen is a national treasure.

If you know anyone interested in photography, news, or fashion, please tell them to listen to this episode. My thanks to Prescott Lee for suggesting Karen as a guest. That was an idea of sheer brilliance.

My thanks to Peg Fitzpatrick and Jeff Sieh, who I consider national treasures.

I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People. Live a long time, wear a mask, and stay away from crowds. Mahalo and aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

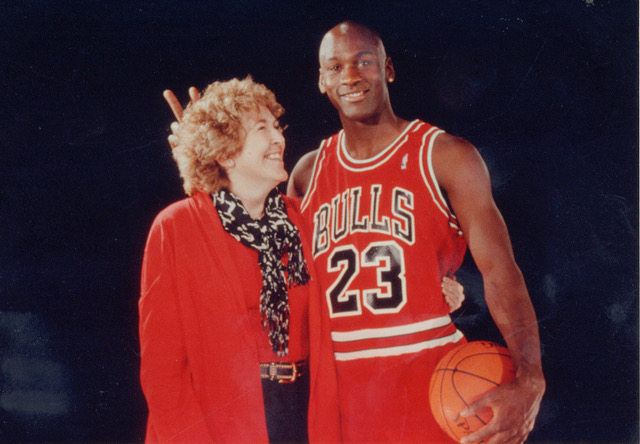

Please enjoy the photo gallery below by clicking on the images. The photo of Karen with sunglasses is by Annie Leibovitz.

Guy, I have been religiously listening to all remarkable people podcasts..some I have been through more than once! This one though takes the cake. Karen Mullarkey’s interview is so inspiring. I hope someday I have a career from which I can tell stories about remarkable experiences. Karen is a great storyteller. Thank you for bringing this to us.

I love(d) film photography. This young lady is cool.

Hey Guy! Muchos mahalos. Stay healthy.

Sincerely,

Brian Kim

Honolulu Hawaii

Wonderful interview. Been thinking about it on and off for days since I listening. Truly a remarkable life.

Its always great to hear the unfiltered thoughts that come from the mind of a creative. Thanks Karen and Guy!

I’ve known (and loved) Karen for decades…last time we saw her was at her place for dinner just before we all locked down…this was an awesome interview.