Luvvie Ajayi Jones is an author, speaker, podcaster, and Nigerian wild woman. She moved from Nigeria to America at the age of nine. She graduated from the University of Illinois, where she started as a pre-med but gave that up when she got a D in Chemistry.

Her first book was a New York Times bestseller: I’m Judging You: The Do-Better Manual. She is just about to release her second book: Professional Troublemaker: The Fear-Fighter Manual.

Here are two standout quotes from the book:

“If thinking highly of myself and being self-affirming is a fault, I want to be the walls of the Grand Canyon.”

“Black trauma is never given space to heal because we have to make sure the white people who hurt us don’t feel too bad about it. Even as victims, we’re told to care about the feelings of those who harm us.”

Her TED talk, “Getting Comfortable With Being Uncomfortable,” has been watched over 2.4 million times.

In Professional Troublemaker, she also quotes the best insult that I’ve ever heard:

“If I want to kill myself, I would climb to your level of stupidity and jump to your IQ.”

Apparently, Nigerians are very good at insults, and that is something to admire.

Buckle up for a riotous episode of Remarkable People.

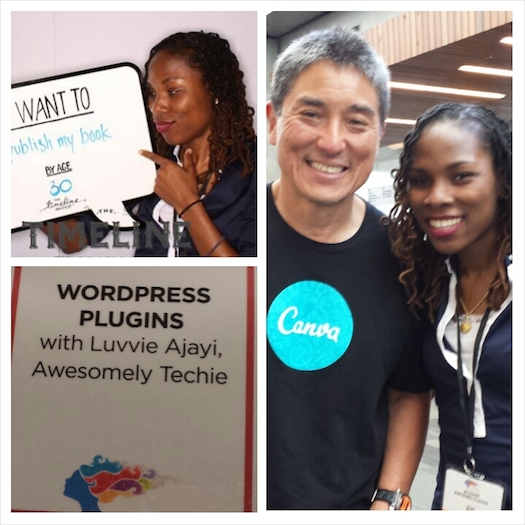

Now listening to @iLuvvit, professional troublemaker, on the #Remarkablepeople podcast! Share on XLuvvie and I at the Blogher conference in 2014. Note her “I want to publish my book” message which became a New York Times best-seller.

Listen to Luvvie Ajayi Jones on Remarkable People:

I hope you enjoyed this podcast. Would you please consider leaving a short review on Apple Podcasts/iTunes? It takes less than sixty seconds. It really makes a difference in swaying new listeners and upcoming guests.

Sign up for Guy’s weekly email at http://eepurl.com/gL7pvD

Luvvie Ajayi Jones is the author of the New York Times bestseller, I’m Judging You: The Do-Better Manual, and is currently working on her second book, Professional Troublemaker: The Fear-Fighter Manual, which will be released in March 2021.

Want to try Classic Nigerian Jaloff Rice?

Connect with Guy on social media:

Twitter: twitter.com/guykawasaki

Instagram: instagram.com/guykawasaki

Facebook: facebook.com/guy

LinkedIn: www.linkedin.com/in/guykawasaki/

Read Guy’s books: /books/

Thank you for listening and sharing this episode with your community.

Guy Kawasaki:

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. This episode's remarkable guests is Luvvie Ajayi. She is an author, speaker, podcaster, and Nigerian wild woman. She moved to America from Nigeria at the age of nine. She graduated from the University of Illinois where she started as a pre-med, but gave that up when she got a D in chemistry. Her first book was a New York Times Best Seller, I'm Judging You: The Do-Better Manual.

She just released her second book, Professional Troublemaker: The Fear-Fighter Manual. Here are two quotes from that book, "If thinking highly of myself and being self-affirming is a fault, I want to be the walls of the Grand Canyon." Second quote, "Black trauma is never given space to heal because we have to make sure the white people who heard us don't feel too bad about it. Even as victims were told to care about the feelings of those who harm us."

Her TED Talk, Get Comfortable With Being Uncomfortable, has been washed over 2.4 million times. In Professional Troublemaker, she also quotes the best insult that I have ever heard, "If I want to kill myself, I would climb to your level of stupidity and jump to your IQ." Apparently, Nigerians are very good at insults. And that is something to admire.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People. Buckle up for a riotous episode of Remarkable People. And here is Luvvie Ajayi.

Speaker 2:

I've been a huge fan of yours for like over a decade. So this is a full-circle moment for me.

Guy Kawasaki:

You say that to all the podcasters.

Speaker 2:

There's actually a picture of me and you from... We met very briefly, like second at... It was a Focus 100 or South By Southwest long time ago.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, you know that I did not write Rich Dad, Poor Dad, right? This is Kawasaki.

Speaker 2:

Listen, I know that it's not you.

Guy Kawasaki:

First question is, do you know who Dorothy Parker and Fran Lebowitz are?

Speaker 2:

I know who Fran Lebowitz is. Yes. I don't know who Dorothy Parker is.

Guy Kawasaki:

You could make the case that Fran Lebowitz is the new Dorothy Parker. I think you are the new Fran Lebowitz.

Speaker 2:

Wow.

Guy Kawasaki:

That you are the young black Fran Lebowitz because I just love the sarcasm and acerbic nature of your writing. I'll give Dorothy Parker quote so you can understand where she's coming from.

Speaker 2:

Okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, quote, "If you want to know what God thinks of money, just look at the people who gave it to." Okay.

Speaker 2:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

And so then Fran Lebowitz says the opposite of talking isn't listening. The opposite of talking is waiting. And then Luvvie says, "If thinking highly of myself and being self-affirming is a fault, I want to be the walls of the Grand Canyon." Oh my God. What a great quote.

Speaker 2:

Thank you.

Guy Kawasaki:

Holy cow. You can say you heard it here first. And then, I'm just going to fan boy here for a while. I'm going to read you another of your quotes. This is more serious.

Speaker 2:

Okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

But take a dagger and stab it. So the quote is, "Black trauma is never given space to heal because we have to make sure the white people who hurt us don't feel too bad about it. Even as victims, we're told to care about the feelings of those who harm us." What a great quote. Do you sit around figuring out how can you be that insightful and decisive? Does that just come naturally?

Speaker 2:

I don't sit around thinking about random things to say, but when I'm thinking through what I want to say, I am hoping that I say it in a way that connects with people, that stays with them. And I never know whatever that thing is, so I always love hearing what part of my writing somebody connects with, because it's always different. So hearing these quotes right back to me and knowing this is what stuck with you, I'm like, this is meaningful. Because I keep track and be like, okay, so that connected with somebody, that made a difference,

Guy Kawasaki:

It made a huge difference. Maybe you could start off by explaining... The nature of podcasting is I sometimes have to ask you questions that I know the answer to. I'm sorry. But the people who are listening don't know the answer. All right? So tell us about the path from Nigeria to America.

Speaker 2:

Yes. So I was born and raised in Nigeria. And when I was nine, we moved to the United States. My mom wanted my sister to start college here and not there. Fish out of water, complete culture shock. Because coming from Nigeria, everybody looks like me. My name was never different. It didn't feel different to anybody. The way I spoke wasn't different. So being nine, the last thing you want to do is be different from the rest of the people around you.

So when I started school, which I didn't realize I was doing, I thought we were actually coming to the United States on vacation, because we'd been here before on vacation. Nobody tells the baby, okay? Nobody consults with the baby of the family. So when we showed up and I was enrolled in school, I was like, oh my God, we're staying? And yeah, we were staying.

And I basically did what kids do. I adapted. I learned how to lose most of my accent by just listening to my fellow classmates. And by high school, most of my Nigerian accent was gone. But being a child of Nigeria that I am, I was still bringing jollof rice to school for lunch. Because I tried to bring in sandwiches a couple of times, it didn't go well for me. Okay? I was like, I'm still hungry. So tomorrow I'm going to come back to my jollof rice. And that's what I did.

So high school happened. I fit in. I had a great group of friends. But one of the things that I actually brought with me on the journey from Nigeria was my dream to be a doctor. And for me, it was significant because I was nerdy. I wanted to help the world. And I thought being a doctor was the best way to do it. A lot of people can relate to the fact that if you have parents who were immigrants, a lot of times they think you should be a doctor or lawyer or an architect.

Guy Kawasaki:

Same goes with Asians.

Speaker 2:

Exactly.

Guy Kawasaki:

Just FYI.

Speaker 2:

Basically, cousins in that. I have a lot of friends who are Asian, who basically we're all the same. I'm like, absolutely. So when I started college, my major was psychology pre-med, because doctor. And I took chemistry 101. And, Guy, I got the first D of my academic career. The first and last D. Because I'm actually not that great at science. And I really understood, in that moment when I got the D, that I would be the worst doctor ever. I don't even like hospitals. So I instantly was like, hmm, let's drop this dream. And you know how oftentimes people tell you, never quit. No, no, Some failures points to the fact that you should quit.

Guy Kawasaki:

I have a similar story, but I quit even faster. I went to law school for two weeks and I just couldn't stand it. So I quit. You didn't tell your mom right till graduation that you weren't pre-med?

Speaker 2:

yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

I told my father right away. And to my utter amazement, I thought he was going to say 15 generations of Kawasaki work to get you into law school and you quit after two weeks. Suicide is the honorable thing for you too. But he said to me, it was not that big a deal. As long as you do something with your life by your mid-twenties it's okay. So I wanted to say to him, so why didn't you tell me to go to law school if it was oka? But anyway.

Speaker 2:

I love that. Because I didn't tell my mom until graduation, because I also was like, "Hey, I graduated four years. You're welcome. You never got a phone call about me getting in trouble in college." I figured the amount of trouble I could get into was minimal.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah. Well, she did just spring it upon you, "Welcome to it."

Speaker 2:

Welcome to... It was payback. It was my version of payback.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's good.

Speaker 2:

It was never going to payback. But it's really funny because that semester semesters I was dropping psychology. And as I was dropping pre-med, I kept psych, but I started blogging. My friends peer pressured me into blogging. Back then it was called web blogging, as you know. So I had a blog on Zynga, and I think it was called Considered This The Letter I Never Wrote. It was really emo as in comic sense. So it was terrible. All about my undergrad career and the exams I was failing and the roommate beefs I had, but it was the first time I really did writing outside the classroom, writing that was not being graded. And I fell in love with it.

When I graduated, I actually deleted that college blogs. And I was like, "I don't have material from undergrad anymore. You know what? I'm going to now talk less about me, more about the world." So I started [offmeluvvie.com 00:09:52], which I still have, and decided to talk about the world, race, feminism, TV, movies, shenanigans, and random good times. Anything that I felt like talking about. And it took on a life of its own. And I had to admit that I was a writer. It took me a bit, it took me about four or five years to admit that this thing that I was doing was more than a hobby. I started winning awards for it. More people that I knew started reading it. And yeah, you fast forward, a whole bunch of other things happened,

Guy Kawasaki:

Next thing Oprah's calling you.

Speaker 2:

Oh my God. I'm a 16-year overnight success. That's what I find myself. I'm a 16-year overnight success.

Guy Kawasaki:

Thank God that you got a D in chemistry, because the world would not be as good a place if you were just a doctor right there. Well, I know all the doctors are going to get off with me saying that.

Speaker 2:

Here's the thing, though. There's so much value in every work, including being doctors, which is why I understand that it was not where I was supposed to go. I would be the worst doctor ever.

Guy Kawasaki:

I would be the worst lawyer. So we have something in common [crosstalk 00:11:03].

Speaker 2:

See? There we are. We're a failed doctor failed lawyer.

Guy Kawasaki:

Before we get off Nigeria, I have to ask you something. I'm going to read you something from your book. As you can tell, I really read your book.

Speaker 2:

I love it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah. This is not something like I looked you up in Wikipedia and try to blow through my way of interviewing. And this is not a quote of what you said, but the fact that you put it in your book is powerful enough. This is the best insult I have ever heard in my life.

Speaker 2:

Okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

And the insult is, "If I want to kill myself, I would climb to your level of stupidity and jump to your IQ." Now, I'm going to put that on my grave marker, okay? But I just want to know, I hope this isn't racist, but how did Nigerians become so good at insulting people?

Speaker 2:

Nigerians are the most chill-deficient group of world dwellers you will ever meet. And we are so kind, but we have also the sharpest tongues ever. Because, as a culture, we actually just insult each other as a love language. It is just part of the way we communicate. We will see each other and be like, you're such a goat. We will call you an animal as a way to say hi.

Nigerians, we like to laugh. We like to find the absurdity in the world. And Yoruba, which is a specific tribe that I'm a part of, is very metaphorical and very descriptive. Just the way the language is. The way that people use words, it lends itself to insulting people in really interesting ways.

So yes, that insult when I first saw it, I saw it on somebody... I don't remember where I saw it. But it's somebody Nigerian that said it. And I was like, my God, we are excellent at the game of lambasted people. We are excellent at it.

Guy Kawasaki:

How do I become honorary Nigerian? What's it take?

Speaker 2:

Guy, the first thing we have to do is get you some Nigerian jollof.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay.

Speaker 2:

Have you ever had jollof rice?

Guy Kawasaki:

Not that I know.

Speaker 2:

Okay. Guy, what city are you based in?

Guy Kawasaki:

Santa Cruz.

Speaker 2:

Santa Cruz?

Guy Kawasaki:

Bay Area.

Speaker 2:

Bay area?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah. San Francisco, Bay Area. Yeah.

Speaker 2:

Okay. I can probably find you a Nigerian restaurant that can deliver you some jollof rice. So jollof rice is the rice of the country. I think most cultures, besides American culture, most cultures have a rice that is their standard rice.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yep.

Speaker 2:

Ours is jollof rice. It is tomato-based. It's similar to Spanish rice, but it's a bit more spicy. Got a little bit more kick to it. It is at birthdays, weddings, random Tuesdays. It is just our dish of choice. So the first thing we got to get you is to taste some jollof rice. All right?

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay.

Speaker 2:

And then from there, you got to get a Nigerian friend. And, Guy you officially have Nigerian friend. Me.

Guy Kawasaki:

You're the only Nigerian I know. Well, there was the prince that I sent 20 million bucks to help him get his money out. But besides him, I only know you from Nigeria.

Speaker 2:

Well, Guy, now you have a Nigerian friend. And then the third thing... I am so sorry, you missed it by a year and a half, I wanted to invite you to my Nigerian wedding. You got to attend one Nigerian wedding.

Guy Kawasaki:

But I went to your wedding now, I would be right on time according to Nigerian punctuality. No?

Speaker 2:

This is true. This is true. Listen, so I got married September, 2019. And, Guy, let me tell you about Nigerian weddings. They are... Have you ever been to an Indian wedding?

Guy Kawasaki:

No.

Speaker 2:

Oh my God. Guy, you need some more Indians and Nigerians in your life because they're very similar. That's another cross-cultural overlap. We're so similar. Our weddings are carnivals. They are three-day affairs. And you will eat, drink, and dance your whole life away. But you got to put at least one. you got to at least one.

Guy Kawasaki:

Your wedding is still going on then?

Speaker 2:

Right. Don't worry. My vow renewal, you can turn up also. So give me about five, 10 years. We'll have a vowel renewal and you can come to that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do it at South By Southwest. Kill two birds with one stone.

Speaker 2:

Oh my God. Kill two birds with one stone.

Guy Kawasaki:

I want you tell me about your grandmother because, well, half your book is about your grandmother. So tell me about your grandmother.

Speaker 2:

Oh, my grandmother. So what's funny is I got the idea to write this book realizing that I wanted to write a book all about fear of fighting and how, when I decided to make the choice to live life boldly, my life changed. When I really got a concrete idea of what this book was about, I was on a plane headed to Paris for a conference. And the line came in my head. I come from a long line of professional troublemakers, especially my grandmother for me, Funmilayo Faloyin. And that moment, I was like, that's what this book is about. She's at the core of this book.

My grandmother was a Nigerian elder states woman who took no shit. Who loved everybody fiercely with the same energy she would insult you with. Who would give you the shirt off her back if you needed it. Who would give you her last dollar if it meant you were happy. And my grandmother was for me a testament of what it looked like to live life without apology, to go through struggles and strive and thrive in spite of them, and to build a legacy that infused the love, the faith, the joy, and come out on the other end and be deeply loved and revert for it.

So my grandmother is the professional troublemaker. I didn't realize I was studying when I was growing up. And who I am today is somebody who is proud to carry on her legacy. And this book is coming out 10 years after she passed. So it's the perfect tribute.

Guy Kawasaki:

So it's in your DNA to be a professional troublemaker? You can't help it, basically?

Speaker 2:

I can't help it. It came in the harness.

Guy Kawasaki:

Why don't you explain what it means to be a professional troublemaker?

Speaker 2:

Yes. I like to title my books things that make people go, are you sure? My first book was called I'm Judging You. And I remember people being like, you're going to call a book I'm Judging You? And I'm like, yes, because we're all judging each other, right? We might as well just be clear about what we're judging each other on. And we're typically judging each other on what's not okay. Like what we look like, what we weigh, who we worship or not worship.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Speaker 2:

So when I decided Professional Troublemakers the name of this book, is because I wanted people to also be like, "Woof, troublemaker. That sounds bad." It's not actually. To be a professional. Troublemaker is to be somebody who's committed to disrupting the status quo for the greater good. It is to commit yourself to being somebody who is in any room. And when you are in that room, you are personally responsible for what's happening in the room.

And you know what happens when we actually commit to the community wellbeing? We will make sure that we are using our power to do good, to speak up for people who might not have the voice that we have, or the access or the power or the money or the privilege that we have. To be a professional troublemaker is to exist in this world and say, it is my job to leave this world better than I found it. In a lot of times, it's going to come from me doing something that's going to make me uncomfortable or something that's going to be scary.

But it's important because if we are disrupting what is happening that's not okay, it means we're challenging injustice. It means we are challenging something unfair that's happening. It means we're fighting for something greater. And I think that's important.

Guy Kawasaki:

And how do you push past the fear and doubt?

Speaker 2:

Yeah, that's big. I think, one, by acknowledging it. One of the things that we do as humans is we utter each other very well. We are very quick to talk about how we're different. But one thing that's really universal. One thing that we all have is the fear of anything. It might be small one day, it might be big another day.

But I realized that fear exists for us for a reason, but we use that reason for everything. So the same fear that keeps us from not putting our hand in fire, we'll use that same thing to stop us from challenging an idea that comes up in a meeting we're in that's not thoughtful and will not serve us.

So when we realize, okay, I am going to be afraid, even when it's small moments, recognizing that's okay, and then saying, okay, now I will move forward regardless. For me, I think fearlessness is knowing that you will not do less because of your fear. That you will be afraid of the small and the big moments, but you insist that it will not stop you from doing what you have to do.

Guy Kawasaki:

I love that. Now, I love your concept of too muchness. So what's the benefits of too muchness.

Speaker 2:

Yeah. Yeah. Yeah. We've all been called too-something. You're being too loud. You're too aggressive. Or you're too passionate. Or you're too sensitive. And I realized that when somebody says we're too-something, it means they want us to be less than. It's easier to say you're too much than to say I want you to be less than you what you are right now. Nobody will say I want you to be less. They just make it say, you're too much.

And we've all faced it in different ways. We've all had moments when people criticize us in that way, but they think they're doing us a favor. They think it is somehow helping us. But oftentimes I think that we are too is usually our superpower. For me, when I was young, I was told I was too chatty. I talked too much. That thing that I was too, well, I now get paid a lot of money as a professional speaker, as a thought leader. So had I let people convince me that I talk too much, the practice of using my words that come out of my mouth to touch people and pass on information, whether small or big, I would have squelched it. I would've been like, you know what? Do less. Be less.

So I want us to understand that in this world that is asking us all to be as the same as possible, that is asking us not to be different, that being that makes you too different. That thing that makes somebody uncomfortable about you is often a superpower that if wielded responsibly and well, you can change the world with it. Or you can change the room that you're in. I'm not going to asking everyone to change the world, change the room.

Guy Kawasaki:

But when and where and how do you draw the line?

Speaker 2:

Hmm. It depends. You have to figure out what your role is in any room that you're in. And it's not always you being louder than anybody else. It's not always you doing something that feels physically disruptive, right? Sometimes it's in having a meeting before the meeting where you say, are we aligned on this? Will you back me up if I challenge this?

How you decide the when and the why and the how, I think it's sometimes in the moment. So if you are sitting in the meeting and an idea does pop up, you have to decide on what your power is. I think oftentimes we leave our power behind or we forget we have it with us. So we think, oh, it's somebody else's job to call that out. If it's a bad idea, I'll be quiet, because somebody else is going to call that. Well, if that person's not there that day, or that person just doesn't feel like being bothered, it's your job.

I think we need to understand that power that we're constantly walking in rooms in. Because power is dynamic. It shifts depending on any room that we're in. I often speak in keynote at conferences. And I always know the 50 minutes that I have the microphone, I am the most powerful person in the room. When I say, thank you and I get off the stage, that shifts. The power in the room now is whoever is the next one holding the mic. But while I have the mic, I understand that my power in that moment is to speak for somebody who couldn't say something in that meeting. Is to make sure that somebody who's listening, who didn't feel empowered to speak up because they felt like they would be punished for it, hears their voice through mine.

Identifying your power in the room and knowing when you don't have as much power is really important, because you can wield it depending that room. So some rooms, you might be the intern, you might be the person who just started, who no one really is like, we can't really give them credence. Other rooms, you might be the person running the meeting. So if you are the person running the meeting, you understand and you know what? Maybe the way I'm going to use my power right now to give it to the intern and say, "What do you think? Let me give you room to speak. As this whole room is making their voice heard, we haven't heard from you."

So it always depends in the small moments. In the big moments, if we haven't practiced those small moments, we really don't have the practice to do it when it's calling for us to do it really loudly or really big.

Guy Kawasaki:

Would you say that humility is overrated?

Speaker 2:

Yes and no. I think humility, the way people describe humility is overrated. Absolutely. When humility feels like you bending yourself backwards, to not own how amazing you are, that's overrated. But I think humility is being clear about who you are and being clear about how amazing you are, but also not being afraid to give credit to those who allowed you to be that amazing.

So I can be humble by telling you I'm an amazing writer and a speaker, but I know that I was able to do this because of my grandmother, because of her legacy, because of my mother's work in bringing me to the U.S, and any sacrifices she's made, because of the teachers who insisted on pouring into me and who allowed me to sharpen my pen. So I'm humble in that I know that my gifts are not just purely because of my work, but I would not be humble by diminishing my gifts. And by saying, I am less there, and reducing.

Guy Kawasaki:

Closely related to humility is the impostor syndrome. So have you gotten over that?

Speaker 2:

Guy, imposter syndrome shifts, man. It shifts. I think-

Guy Kawasaki:

Where is it now?

Speaker 2:

Where's it now? Ooh, that's good. So my imposter syndrome before it looked like me being like, do I belong in the room? Because I'll find myself in rooms. I mentioned to you how I met you 10 years ago, very briefly, at a conference, and me being like, "Oh my God, how did I get into a room where Guy Kawasaki is breathing the same air? Like what? That's crazy." Right?

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh my God.

Speaker 2:

I was like, oh my goodness.

Guy Kawasaki:

So let me get my boots. Oh my God.

Speaker 2:

And as my career shifts, as my career levels up, as I find myself in even more rooms and with more people that I'm just like, whoa, I'm in this room, imposter syndrome now doesn't look like, how did I get here? Because I know the work that it took for me to get here. Now it becomes, what work must I do to stay here? Now imposter syndrome is being like, do I have to constantly innovate? Do I have to constantly over prove myself to feel like I can stay in the room?

So it's a constant work in progress and acknowledging that and saying, I can say that out loud. I can say I have no problem being like, I am feeling a piece of fear here, I am a bit nervous about the fact that I'm in this rarefied air, but also understanding that it is the constant work of knowing that the work that I've done is enough, right? To keep me here. The person, the name that I've built for myself is enough. The voice that I have is enough. And I don't necessarily have to constantly strive.

Guy Kawasaki:

Don't you think you could make the case that if you are someone who never has any thoughts of imposter syndrome, that you probably are an impostor?

Speaker 2:

Yes. Yes. Absolutely. I find that imposter syndrome, the people who say I never have it are people who aren't constantly looking to be better because they already think they've reached the peak of wherever they must go to. And I think everyone should be a forever student. I don't ever call myself an expert at anything because if I call myself an expert, that means I'm saying I have no more to learn. Right?

So people who don't have any imposter syndrome are people who are like, I have nothing more to learn. I am already the best thing since sliced bread. And that is an extra piece of arrogance that I don't think I ever want to get to. I always want to think I'm dope. I always to think I'm amazing. But to say I am the best I will ever get to, means I have stopped growing as a person. And that sounds like I am dying, like willingly died.

Guy Kawasaki:

What is it like to be young, black, female, and Christian in America today?

Speaker 2:

Oh, we. Young, black, female, Christian, smart, caring about the world, it is deeply frustrating. Frustrating is an understatement. Because to be a young black woman in America, who believes in God, and cares, and finds that what I pick out of the Christian is the fact that Christ laid himself on the line for other people's wellbeing. That piece is really important. And that piece is what I think a lot of people are missing.

When we talk about this racist structure that we live in this country that is deeply unjust to people who are marginalized, that part drives me nuts. This country that purports itself that puts in grad, we trust on the coin, but does not put God-like policies forward. It's deeply frustrating because we're living in a world of others dichotomy, all this hypocrisy. And for me, I'm like, are we all talking about the same guy? Are we all talking about the same concept of love your neighbor? There's the golden rule and there's the platinum rule. Do unto others as you want to be done unto you, and then, do unto others as they would like for you to do for them, is really significant and we don't do it.

So, yeah. And that's part of why I use my voice. So I was like, I hope when people encounter my work, whether it's in my book, whether it's in my podcast, whether it's just out in social, I hope people find things that compel them, that I said, that makes them think, "You're right. I can do something different, something better." Because for Christians to live in this country and be okay with kids in cages, to be okay with us saying people can't marry the people they love simply because they are a different gender identity, for us to say, it's okay for people to go without food when some people are there like, they'll throw out food just because. I don't understand how we can be okay in a world where there are kids starving, and where people have no homes to go to at night. So yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

What Kind of systematized racism do you still experience?

Speaker 2:

Oh. I have been a public speaker for 10 years, professionally, I have a TED Talk that has five million views, I've spoken at some of the world's most innovative companies and I still have to fight to get my fee. I will show up, change hearts and minds and 50 minutes, and I still have to over prove why I charged my large five-figure fee.

For me, I get to see white men who don't have the credentials I have, who don't have the experience I have, who, without question, get what they charge all the time, every time. Who are offering nothing of value or very little value. Who are saying they have no imposter syndrome because they've never had to face somebody doubting who they're simply because they look like that. Right?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Speaker 2:

Racism changes. The racism that we encounter changes even... And still always based in the same thing is that when I show up as who I am, this woman that I am, whether I am in a blazer or whether I'm in a sweatshirt and a baseball cap, people have all these ideas of who I am and what I bring to the table, and my intelligence, and the way I can speak. And people still be shocked that I can speak well when I'm like, I have a college degree, I can speak two languages. I've been reading since I was three. So for me, the structural racism shows up as I am amazing at what I do and I still have to over prove that I am worth what I charge.

Guy Kawasaki:

With all of this, what is your advice to a young black woman in America right now?

Speaker 2:

Be dope anyway, even when people don't expect it or believe it. What we can do, what I would tell any young black girl, and why I always want to show up in the way I show up because I hope I am a model for somebody who sees me show up exactly as who I am. I write in the same voice. Whether I'm speaking at a Fortune 50 company or at a non-profit in Chicago, I'm speaking in the same way. I'm probably dressing the same way. Sometimes I'll go to a conference that's business casual wearing Jordan 1s just to prove a point that excellence can show up whether it's in the soup or the sweat pants.

So I want a young black girl who is listening to this or who needs some type of pump to know that if she didn't get the permission before to be herself, to be her full dope, excellent self, I hope I am giving her permission to be that because I am proof that you can be that and still you can thrive. You won't just succeed, but thrive. Stand in it.

Guy Kawasaki:

You had another statement that just totally intrigued me. And I want you to explain this for my listener. Which is, why do you say that black women are the moral center of the universe?

Speaker 2:

Hmm. I think black women are the moral center of the universe because we are constantly thinking about the wellbeing of the world, because we know what it's like to be the ones whose heads are stepped on. So we don't want somebody else to feel like that. So our actions and how we show up is with the intention of, I want to make sure that I am not stepping on somebody else's head. And when that happens, it means you're constantly about how to make sure everybody's okay.

We are the moral center of the universe because how we think, we nurture deeply, we know what it's like to constantly be battled. And we want to make sure that it happens less for those who look like us. But here's the thing, is when black women win, everybody else wins. When black women are at the helm, everybody else wins. When we think about even what happened in Georgia, right? When everyone's, oh my gosh, we got to save democracy, black women, put it on their backs and say, you know what? We will do everything we can to make sure we can get this thing happening. But when that thing happened, it was for the betterment of everybody. When the work that we do is usually for the betterment of not just us, but everybody. So that's why I think we're the moral center. If the world listened to us more, it'd be better for it. Then you've better food.

Guy Kawasaki:

I would make the case that Stacey Abrams may have saved America.

Speaker 2:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

Literally.

Speaker 2:

Stacey Abrams and the work of black women like Natasha Brown, [inaudible 00:35:39], it's been like a Voltron of black women who were like, we're going to do this work. And we helped save America. And everyone kept on hashtagging, believed black women or trust black women. But you know how you trust black women? You move out of our way and you stop sabotaging us. You move out of our way and listen to us. If you just do what we say do, things would be so much better.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh my God. You are priceless. Okay. Now, there's one part of your book and your background that I just don't understand what happened. And this is of course the Tevin Campbell experience.

Speaker 2:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

So what the hell was that about? Why did it go? So off the rails? What am I missing? I'm just maybe a 66-year-old Asia-American, so I don't understand this, but can you explain that whole thing to me? And now with two years of hindsight, maybe you can interpret what the lessons are.

Speaker 2:

There's a chapter in this book called Fail Loudly, and that was the biggest public fail I've ever had. And God, let me tell you, even today I still can't fully explain to you why it blew up so much. I don't know what about it made it so loud because I have said stronger things. I have said stRonger things and off way more people before, but for me-

Guy Kawasaki:

Maybe we should explain it because people may not know what the hell we're talking to.

Speaker 2:

Yeah. Like Aretha Franklin died and everyone was talking about who should do her tributes. And somebody Tevin. And I love Tevin Campbell. I actually love his music. And I was just like, that's a random name to tie to Aretha Franklin. Under what rock did you pull that name from? Is what I said. It went too shit. I'm trending on Twitter for an hour the day after, mind you. It wasn't immediate. And people were calling me anti-black American. People were saying that I didn't know anything about music and culture. And I was stunned into silence for like... I mean people tried to destroy my career over this one tweet.

Literally, somebody actually went on Twitter and Facebook and said I want to destroy her career. And I was like, holy shit. And one thing I learned in that moment that I talk about in the book is about how what was different was not necessarily what I said, what was different was how people would see me. And I think it also comes down to this fact that people really want to humble black women in a big way. When you stop being the underdog, you become the target.

Back in the day when I was just the person behind a computer screen, who still had a full-time job, who still had the struggling blog, who only had 10,000 followers, that thing wouldn't have made a difference. Whatever I said, didn't make a difference. What people saw was the love you, the platform, the brand. And a lot of times people do want to humble black women and say, "I don't like how far you've gone. Let's get you back into your place."

So I feel like a lot of that happened, but I think it was also a signal for me to understand, "Luvvie, you're not just love you from Chicago in Nigeria anymore. You are an entity now. You're like an empire. You're no longer David you're Goliath." And when you're Goliath, people want to throw the rocks at you. So what you do is understand that if you're seeing yourself as David, because you're being humble, if you're seeing yourself as David, you also have to recognize that at one point you are Goliath, your words do reach more people, your words do have more power and impact. And understanding that I needed to wield my platform even more responsibly was the gifts that I got from it.

Guy Kawasaki:

And two years later, do you think it has made any difference to the arc of your life as you did then?

Speaker 2:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

It has?

Speaker 2:

Absolutely.

Guy Kawasaki:

Because of what you learned, but not because of the damage that it did to you, right?

Speaker 2:

It definitely. It took air out my sales for about a year. It really did. It took me a minute to get my footing back on it, to be able to be like, "Okay, I stopped being afraid of my own voice." I think one of the gifts was, funny enough, it brought more followers me, which was weird. When you're in firestorm, people were like, "Who's this Luvvie girl people are talking about?" And then people being like, "Oh my God, I love her."

So it got more people following me. That was one. But, two, I think it also kind of... Every experience that we have, it's hard to remove what the domino effect is to our lives. It really is. Because that moment and how it sat me down, had me thinking through who I wanted to show up as in the world, what I wanted my career to look like, what I needed to put into place for the fact that I am bigger than I thought I was. How I needed to even build my team different. Got me thinking about and asking questions that I wasn't asking myself before.

And I think those questions also now helped, because I started going to therapy even more. And my therapist is quoted throughout my book. Because in that process, she was walking me through what it meant that this thing happened. How was I going to grow from it? And that was a gift that shows up in this book. My therapist, who actually just passed away two weeks ago. And I think about that moment and I think about what he was asking of me. And I think about the growth that he was asking of me. Who I was then could not handle my success now. Because maybe I don't think I was equipped for it. I had to go through that firestorm to get me the equipment that can push me past it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Which leads me to my next question. So you came up with a list of three things to ask yourself before you ask other people or say things. And I think that is a great list. So what are those three things to ask yourself before you do something?

Speaker 2:

So it is important for us to have a checklist that makes us less impulsive, especially when it's time to say hard things. Because a lot of times people are asking like, "Okay, so what makes you decide to do it? How do I make sure I'm not talking out the side of my mouth?" And I think having a checklist and quantifying our decisions is usually the best thing.

So one is, do you mean it? This thing that you are saying, is this actually something you believe, or are you saying it because you just feel like being a contrarian in the moment? Can you defend it? If somebody challenges you on this thing that you say, do you have the receipts to prove this right? Or where your opinion is coming from? Can you basically stand in this thing that you're saying? And then can you say a thoughtfully or with love? Because the way you provide a message actually does matter.

So it might be a valid message, but if you're saying while it's being hateful, you won't land. So is there a way that you can say this in the way that it's most thoughtful possible? If the answer is yes to all three, say it. And then whatever happens, happens, you deal with it. But I think that checklist is at least really good to affirm you in those moments when you do want to speak up but you're not sure whether you should.

Guy Kawasaki:

You discuss what it means and how to be a good taker or recipient of stuff.

Speaker 2:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

So explain to us, how do you be a good taker?

Speaker 2:

Yes, indeed. I think a lot of times we are very proud to identify ourselves as generous people who give, give, give, but there is something about us that also makes it hard to take. When you are constantly given, you don't feel like you can take. Because in that moment, you're not being generous. You think, I'm the one that's supposed to be given not receiving it. But I think about... And I'm that person too. And I have to unlearn that. It's something that I'm constantly unlearning.

To be a good taker is to be able to say a gracious thank you, is too... Because a lot of us are not even good at receiving compliments. Like somebody will compliment our shirt and we'll be like, "Oh, this old thing, I've had it for a long time." As opposed to being like, "Thank you. I'm glad you like it. Let alone when it's time to receive a gift or something that feels big, that you might not gift yourself. You'll be like, "No, no, no, no. I don't want. No, no. You don't have to do that." No, receive it with gratitude.

And I think one thing we should understand is, when we talk about love, love is not just about being generous. Love is also about receiving somebody else's generosity. Let other people feel the way you feel when you're being generous by taking and by receiving what they're offering you, help energy, time, platform, money. Sometimes it's okay to receive because I think that's the second part of love. If I'm not receiving what you're giving me, how am I allowing you to show me love? So we have to think about it in those ways.

Guy Kawasaki:

Another thing that I found and say surprising or unusual is putting two words together, toxic and positivity. So how can positivity ever be toxic?

Speaker 2:

Absolutely. Hey, too much of anything is not good. Correct? That's a rule that we all know is fact. Too much of anything is not good. You can love vegetables. If you eat nothing but vegetables all day, you're not going to be balanced. Where's your fiber. You love candy? Great. You eat all that sugar? What's up diabetes. Okay?

Too much good positivity is not good. What does that mean? When you walk through the world thinking you should exist in nothing but good vibes and good feelings. Because what happens is when you weaponize your negativity. You weaponize whenever you're feeling bad. You make yourself feel bad for feeling. It's like being in the house in this quarantine.

I was telling you, Guy, we're the privileged ones. We're the ones who are in-house. We don't feel immediate and acute threats. We know where our next meal is coming from. We're not worried about somebody coming into our house. We feel safe. We're the privileged ones. So sometimes even in this... Yesterday I was talking about how I've hit a pandemic wall. If the wall where after 10 months of quarantining, of life not looking anything like it did before, you being exhausted. But to say it out loud, somebody was like, "Well, it's okay. We'll be fine." But the moment of negative emotion is okay. Toxic positivity is the idea that any time we voice or feel something that is not positive, and flowery, and good times, it's that-

Guy Kawasaki:

Unicorns or pixie dust.

Speaker 2:

Exactly. Unicorn and pixie dust and rainbows were somehow being ungrateful for our lives, for the things that we have. No. negative emotions are necessary. They're natural. When you feel them, you might work on not getting lost in it. But the goal is not to be like, "Oh, I have no right to feel this way." No, you have a right to feel what you feel.

So when it becomes toxic positivity is when you are not assuming and living in real life for the sake of bypassing an emotion. Some people call it spiritual bypassing, right? It's the idea that you're not supposed to feel anything bad, you should just be grateful. So that you never deal with the emotions at all. You just surface them. You just gloss them over.

So how you make sure positivity doesn't get toxic? You allow yourself to feel the negativity, you acknowledge it, and then you let it pass. You allow somebody who's talking to you and saying, "Hey, I'm feeling this way." You acknowledge your feelings. You don't dismiss it and you say, "No, you're fine. You should be okay." You make sure that you're not the person who is constantly reducing people to good vibes.

Guy Kawasaki:

And my last question for you is how do you do your best and deepest thinking?

Speaker 2:

Mm-hmm (affirmative). That's good. How do I do my best and deepest thinking? With a pen and paper. I am a visual learner in all ways, in that if I have ideas or thoughts and I don't put them down on paper, I feel fog. It's basically why I am a writer. Because putting my words on paper is cathartic. So my best thinking is in quiet, me and a pen and a notebook. And I have many notebooks. I have a bit of a stationary problem. I need to stop buying them. But I won't. I already know I won't. And I sit there just jotting down my ideas. Sometimes it's bullet list. Sometimes it is fully-formed paragraphs. Sometimes it is some of both. But yeah, I like writing down stuff and thinking through stuff, creating graphs and whatnots.

Guy Kawasaki:

This is obviously called the Remarkable People Podcast. And it is sponsored by a company called the reMarkable Tablet Company. And the reMarkable Tablet is this tablet that has a stylist pencil that feels just like a pencil, not like an iPad and Apple Pen. And every guest gets one. So we're sending you one.

Speaker 2:

Awesome.

Guy Kawasaki:

You will never have to find a notebook again.

Speaker 2:

Cheers.

Guy Kawasaki:

I hope you love it. I hope you love it.

Speaker 2:

I love that. I'm going to definitely try that out and I'll send you a note, Guy.

Guy Kawasaki:

This has just remarkable, shall I say? And delightful. And I'm going to go look for that rice. And I'm going to come to your wedding or wedding... No, that would imply you're getting remarried. I'm going to come to your vowel renewal. And one of my goals in life is to become as close as I can to becoming an honorary Nigerian. You got to have goals in life. And I just want to be able to insult people at that level. But with kindness. With constructiveness and with kindness.

Speaker 2:

Guy, we do with kindness.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes. Yes.

Speaker 2:

Well, we can absolutely lambaste people. No, Guy, thank you so much for having me. I never take it for granted when people want to share space with me and when people want me to share my lessons and the things I've learned in this world. And I told you earlier, I have been a student of yours from afar for about a decade. And the remarkable work that you've done is something that I know leads the work that I do. So in case you [crosstalk 00:51:21] recently, just know you were one of the people who I used to read about and see their work. And I'd be like so dope.

I'm going to find that picture that you and I took when we briefly met at a conference. I can't remember which one. You had on a canvas T-shirt at this thing. I'm going to find it. I'm going to tweet it to you when I find it. And this feels like such a full-circle moment to be affirmed by you, an OG in tech, Guy. Are they tech geek as a person who was at the intersection of all these different platforms? Or like when you and I come off podcasts, I was like, "Say less. When do you need me? I will be there."

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh, Luvvie, you flatter me too much. I don't have imposter syndrome. I deserve that.

Speaker 2:

Oh, yeah. You must receive that compliment. You must've seen that.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's right.

Speaker 2:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

That was all totally do me. Okay.

Speaker 2:

So much appreciate it. And this will highlight.

Guy Kawasaki:

I hope you enjoyed listening to Luvvie as much as I enjoyed conducting the interview. She is truly a remarkable and one of a kind funny woman. This is Guy Kawasaki and the Remarkable People Podcast. I'd like to thank Alisa [Carmahart 00:52:41] Paige for helping me reconnect with Luvvie and getting her on the podcast. My thanks also to Jeff C. and Peg Fitzpatrick who, 52 times a year help, me make a remarkable podcast.

I will keep you posted about getting to a Nigerian wedding. But for Nigerian weddings to occur, at least in the traditional manner, we all need to wear mask, avoid crowds, wash our hands, and get vaccinated. Please remember to do all those things. Mahalo and Aloha. This is Remarkable People.

Sign up to receive email updates

Leave a Reply