These are photos from Core Memory: A Visual Survey of Vintage Computers by John Alderman with photographs by

Mark Richards. There’s a sensual beauty to computers that I never appreciated until I saw these pictures, and I can’t think of a better Christmas gift for a hardware geek.

ILLIAC IV. In 1966, Daniel Siotnik began designing the ILLIAC IV to incorporate 256 processors, each of which would execute the same instruction on different data (SIMD). Burroughs Corporation began construction of the machine at the University of Illinois, but moved the project to the NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, in 1971 due in part to fears involving the project’s military-based funding and student unrest over the Vietnam War. Although only sixty four processors were built, the computer performed useful work, such as wind tunnel simulation, seismic studies, and image processing, until it was decommissioned in 1982.

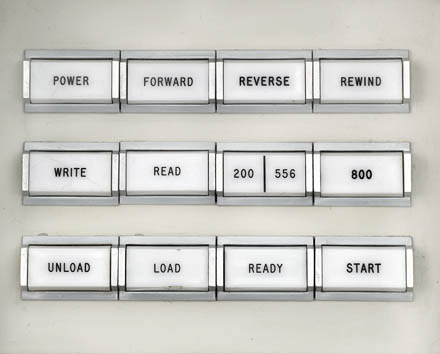

CDC160A. Supercomputer pioneer Seymour Cray once claimed that he needed only one week to design this stand-alone version of his earlier CDC 160. The CDC 160A was often used for dedicated production control applications such as operating typesetting machines and mechanical lathes. It came with a high-speed paper-tape reader, paper tape punch, and a typewriter. A FORTRAN compiler was also available for those who wanted to write their own programs.

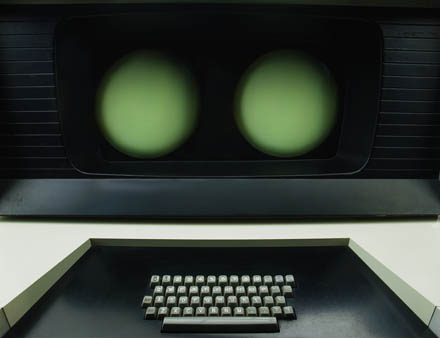

CDC 6600 (Serial number 1). When introduced in 1964, the CDC 6600 was the fastest machine in the world. Designed by Seymour Cray, the 6600 executed about three million instructions per second and remained the fastest machine for five years, until Cray produced his next supercomputer, the 7600. The elegant architecture of the 6600 included one 60-bit central processor with multiple functional units that executed in parallel with ten shared-logic 12-bit peripheral I/O processors. The machine was freon cooled. Selling for $6 to $10 million each, Control Data Corporation (CDC) manufactured about 100 machines.

CDC 6600 (Serial number 1). When introduced in 1964, the CDC 6600 was the fastest machine in the world. Designed by Seymour Cray, the 6600 executed about three million instructions per second and remained the iastest machine for five years, until Cray produced his next supercomputer, the 7600. The elegant architecture of the 6600 included one 60-bit central processor with multiple functional units that executed in parallel with ten shared-logic 12-bit peripheral I/O processors. The machine was Freon cooled. Selling for $6 to $10 million each, Control Data Corporation (CDC) manufactured about 100 machines.

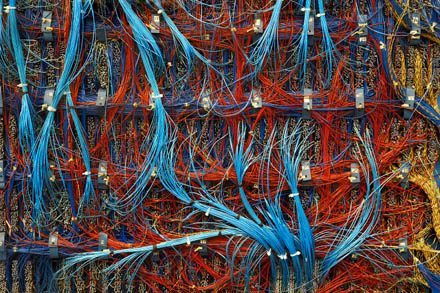

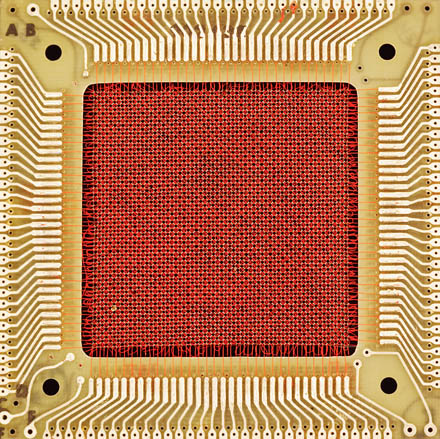

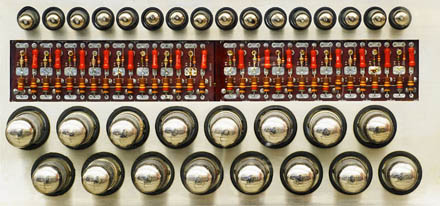

IBM magnetic core plane, 1958.

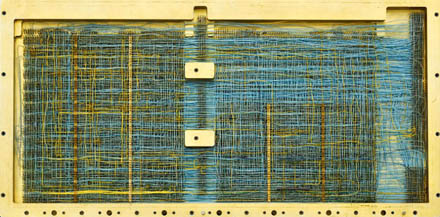

Core memory Magnetic Cor Memory ILILAC II, 1962.

Cray-3, 1993. Seymour Cray chose exotic gallium arsenide (GaAs), instead of silicon, for the circuitry of the Cray-3. The modules in this “brick” comprise a mUlti-layer sandwich of printed circuit boards that contain 69 electrical layers and four layers of GaAs circuitry. II consumed 90,000 watts of power and, like the Cray-2, was cooled by immersion in Fluorinert. Only one complete Cray-3 was built. A computation that took the Cray-3 only one second would have taken ENIAC sixty-seven years.

ENIAC (Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer), 1944. The ENIAC was originally designed to calculate firing tables for WWII artillery, but it wasn’t completed until 1946, Although the ENIAC was not finished in time for the war effort, it was used to do calculations for the hydrogen bomb as well as other classified military applications.

The principal designers were J, Presper (Pres) Eckert and John Mauchly with Herman Goldstine acting as the Army liaison. With about 18,000 vacuum tUbes, 1,500 relays, 70,000 resistors, and 10,000 capacitors, ENIAC was the largest electronic vacuum tube device to have been produced to that time, consuming enough power for 50 homes and capable of 5,000 operations per second,

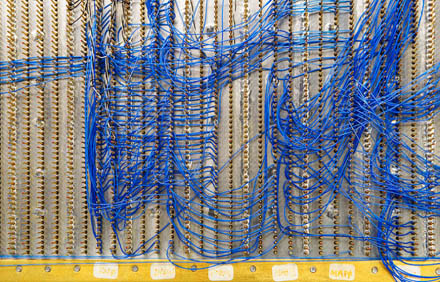

The ENIAC was not a stored program computer, but had to be rewired for each new job. The rewiring problem led the team to think about storing the wire configuration as a “program” in memory, but it was too late to change the design of the machine under construction. The panel on exhibit here is one of forty that make up the ENIAC.

GPS Analog Computer, 1950. Scientists and engineers used the GPS Analog Computer to solve complex industrial problems. A very adaptable machine, the device could be configured to solve a range of problems by adding optional amplifiers, sensors, arithmetic elements, and input/output units to the basic system.

Google’s first production server.

IBM Model 077 Collator, 1937. The Social Security Administration, established by President Franklin D. Roosevell during the Depression, created a huge demand for punched card data processing machines, so that the earning history of every worker could be recorded and used to compute benefits. The collator compared two groups of punched cards and merged them into correct numerical or alphabetical order. The machine could also be used to extract cards from one set that were matched by cards in the other.

Model 7030 “Stretch,” 1961. The IBM Model 7030 was one of the world’s first supercomputers. Originally conceived as an internal development project to improve, or “stretch,” IBM’s computer skills, the first Stretch was delivered to the Los Alamos National Laboratory to aid in the design of nuclear weapons. Only three of the subunits are shown here; a complete Stretch occupied about 2,500 square feel. Stretch did not meet its “100 times the IBM 704” performance objectives, and was initially viewed as a failure by IBM. Nine were built and then no more orders were accepted. Stretch incorporated a dazzling array of technical breakthroughs and was the fastest computer in the world for several years. It is now viewed as a critical milestone in IBM history.

System/360 Model 30, 1965. In April 1964, IBM announced the System/360. This was a new line of unified, compatible computers, and the largest of the machines was forty times faster than the smallest. The line was highly successful and the 360 architecture dominated the mainframe computer industry for twenty five years.

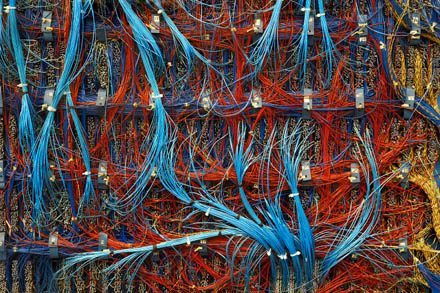

Tape drives of the System/360

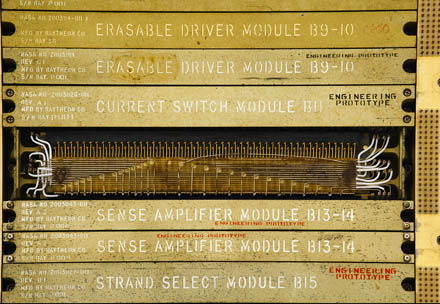

Apollo Guidance Computer, c.1965 Developed by the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory under the direction of Eldon Hall, and manufactured by Raytheon, this is an engineering prototype of the computer that guided the Apollo Spacecraft Command Module (CM) from Earth orbit to the Moon and the CM’s return to Earth surface. It also guided the Lunar Module (LM) irom lunar orbit through its descent to the moon’s surface and return to rendezvous with the CM in lunar orbit. During the critical landing procedure, it accepted manual steering commands from the astronauts to make a safe landing.

Apollo Guidance Computer, c. 1965. Developed by the MIT Instrumentation Laboratory under the direction of Eldon Hall and manufactured by Raytheon, this is an engineering prototype of the computer that guided the Apollo Spacecraft Command Module (CM) from earth orbit to the moon and the CM’s return to earth surface. It also guided the Lunar Module (LM) irom lunar orbit through its descent to the moon’s surface and return to rendezvous with the CM in lunar orbit. During the critical landing procedure, it accepted manual steering commands from the astronauts to make a safe landing.

Diagram of SAGE system elements, 1954. SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) was a large computerized air defense system built in response to the Cold War threat of Soviet bombers. By analyzing radar data in real-time, SAGE provided the Air Force with a picture of the North American airspace and could relay targeting information to fighter planes. In practice, it is doubtful that SAGE could have effectively responded to an invasion.

IBM built the SAGE hardware based on the Whirlwind computer design at MIT The many technical advances include modems for communication between sites over telephone lines, networking, light guns, graphical displays, and reliable magnetic core memory. Each of the twenty-seven SAGE installations had two separate computers, the second serving as a “hot standby” in case the active computer failed. With this backup, availability was an unprecedented 99.6%, when many other computers from that era would fail every few hours. The computer weighed 300 tons and typically occupied one floor of a huge windowless four-story concrete blockhouse. On another fioor, dozens of Air Force operators watched their display screens and waited for signs of enemy activity

Diagram of SAGE system elements, 1954.

UNIVAC I Mercury Delay Line, 1951. Mercury delay lines served as the main memory units for many early computers. Sound waves were sent through a tube of mercury, detected, and returned through the tube. A tube one meter long could contain about 1,000 pulses (bits) and took one millisecond to recirculate these signals. A memory tank for the UNIVAC I had 18 tUbes, each holding ten twelve-character words that could be accessed in approximately 222 microseconds. With ten tanks per computer, the total memory in modern units was about 20,000 bytes.

The WISC (Wisconsin Integrally Synchronized Computer), designed by Gene Amdahl while completing his Ph.D. in theoretical physics, was built at the University of Wisconsin between 1951 and 1955. It was used to train electrical engineering students in the then new field of computing. The machine’s memory was a rotating magnetic drum, the rotation time of which determined the overall speed of the system. It could perform iour arithmetic operations at once, a unique feature for the time. After graduation, Amdahl joined IBM and played a key role in the architectural design oi several important systems including the groundbreaking System/360.

SuperPaint, 1973. Xerox PARC, United States Dick Shoup’s SuperPaint system was a combination of revolutionary software and customized hardware that is the ancestor of all modern paint programs. Its long list of now-common features included a palette of 16.7 million colors, a colormap, adjustable paintbrushes, video magnification, image transformations, video in/out capacity, a tablet and stylus, and animation and image file transfer abilities. The SuperPaint system garnered Xerox and Shoup an Emmy Award in 1983 and, along with Alvy Ray Smith and Tom Porter, a technical Academy Award in 1998.

Wow. Great design certainly has more longevity than computing hardware! Beautiful stuff. (Disclaimer – I am a geek :)

Goooosh…..Such an old crap! LOL

I’ve had this book a while now, and it’s lovely to get it out every now and then and flick through just for the eye candy. There are lots of books about the 80s micros, but this is one of the first that goes back further and deeper in such a visual style. (I am also a geek :)

Guy,

I loved your comments on the art of Mark Richards.

And I hope that you will love this:

Although it would not be too meaningful to give exact dates for the historical computers, it is for ENIAC. All of my university students and graduates know and keep remembering this date: 14 February 1946.

Really cool post. I got to visit the Computer History Museum in Mountain View a couple of years ago and it was amazing. It was also embarrassing because they had at least 3 computers there that I had worked on, the largest (mini) being the DEC PDP8 :)

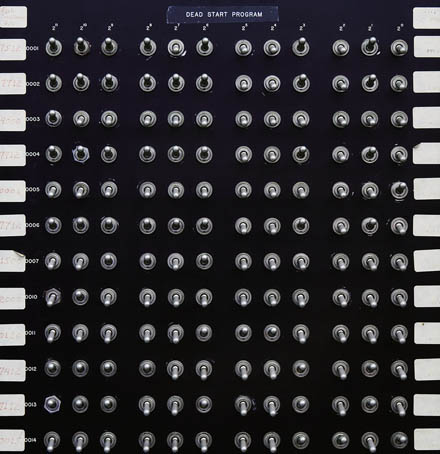

Wow! Thanks for the trip down memory lane. I worked as a CDC 6600 Customer Engineer on sites at Kirkland AFB (Albequerque) and Sud Aviation (Toulouse, France). I also wrote the diagnostics for the black box that allowed two 6600’s to talk to each other – altho CDC couldn’t figure out why their customers wanted/needed that hardware when they could just take a mag tape down the hall. That pic of the 12×12 dead start toggles sure brought back memories.

Now, I need to go find a pic of the first computer I worked on — the RCA 301.

Very nice. Thanks Guy. DGC

Great book. My wife actually got this for me recently and I was amazed at how organic the early computing hardware looked in these images. I guess it’s all a matter of the framing and context.

I was wondering, do the publishers of the book mind that you put almost every image from the book in this blog post?

Perhaps a trip outside now and again would be more useful. While I am familiar with many of these devices, I have to say that most, if not all, pale in comparison to some of the wonders of nature. Just look deep into the complex web of life and you will see wonders that none of these images can compete with.

For the most part, I would say that these images brought back painful memories of fighting with various computers. Nothing makes me swear more than working with computer hardware, except computer software!

Guy, thank you for a great read. History of computer technology is amazing!

How about the history being written now…

MacEnterprise’s sister group,

MacLearning, will be hosting a

webcast entitled Mac OS X Leopard

Accessibility Update on Wednesday

October 31st at 1:00PM EDT (10:00 AM PDT).

This webcast features Mike Shebanek,

Senior OS Product Marketing Manager,

highlighting the latest

accessibility features in Mac OS X

Leopard, like the new Alex voice,

Braille support, and new features in

VoiceOver, that make the Mac user

friendly for those with

disabilities.

The MAC is coming to a station near you…

Accessibility.TV –

It’s the channel every MAC user will watch.

Those Cray supercomputers were indeed a thing of beauty. The Science Museum in London has a partially dissected one on permanent display where you can see the 250,000 multi-coloured wires up close.

I look at those old computers and bar the efforts of Apple (who are not quite perfect), I wonder when was it that computer designers just stopped caring.

My copy of Core Memory turned up about a week ago. Both the machines and the book itself are gorgeously presented. I was a little disappointed at the absence of any Data General gear – can anyone look at a TP2 printing console or a Dasher D200 and not be impressed at their design?

I remember seeing 2-3 Crays in operation at CERN near Geneva in 1971. Very impressive, taking up a huge amount of floorspace.

The Digital Elctronics PDP8 of the late 1960s is not listed but it was imo the first volume built computer for small applications and was a little less power hungry.

Hi Guy;

For the most part, I enjoyed this post. The photos are great. But there are places where you repeat the descriptive text with a different photo and there are a couple of places where the text doesn’t match up with the photo (e.g. describe a diagram and show a photo). And, while the Google production server photo is cool, it seems very out of place here.

Maybe I’m too much of a geek, but editing misses like that call into question the accuracy of the whole article.

I really enjoy your blog and frequently find the information quite useful, but the level of attention-to-detail in this particular post left me scratching my head.

Duane Benson

As a user,with no non-user knowledge,can I beg all you experts NEVER to write the instructions for anything that you devise. Only someone completely ignorant is qualified to write the instructions for any mechanical or electronic gadget. I was given a new graphics card last month. The instructions were written on a piece of paper half the size of a postcard. And they were not only incomprehensible but,as it turned out,wrong.

Guy

I didnt read the text, I just admired the art! It was wonderful, thanks for sharing.

Sheri Smith

I prefer to be able to read your postings in my feedreader. it is very uncomfortable to read that way and makes no sense to me. Why do you force people to come to your blog? Ads?

And we add: 5 years ago Taschen came out with a nice hardcover: “Computer: An Illustrated History” which has been one of our bedtime favorites since then.

In December 1966 I was a fresh tech out of the Air Force. I went to work for Philco Ford on a tracking station at Tule Greenland. I cut my teeth on a CDC-160A. It had an external box about the size of a three drawl filing cabinet that held 32K of core memory emerged in oil to stabilize its temperature. The CDC tech that maintained the computer gave me an assembly language manual for the CDC-160A which started my 50+ year career in software engineering. I spent three months when I was off shift and wrote a word processing program that allowed you to save your document on punched paper tape. Half of the people on the tracking site used that program to write resumes.

I’ll never forget that computer. It leapfrogged me from being the tracking computer operator to the control room where I worked my way up to command controller which meant I got to press a lot of backlit buttons when they were flashing.