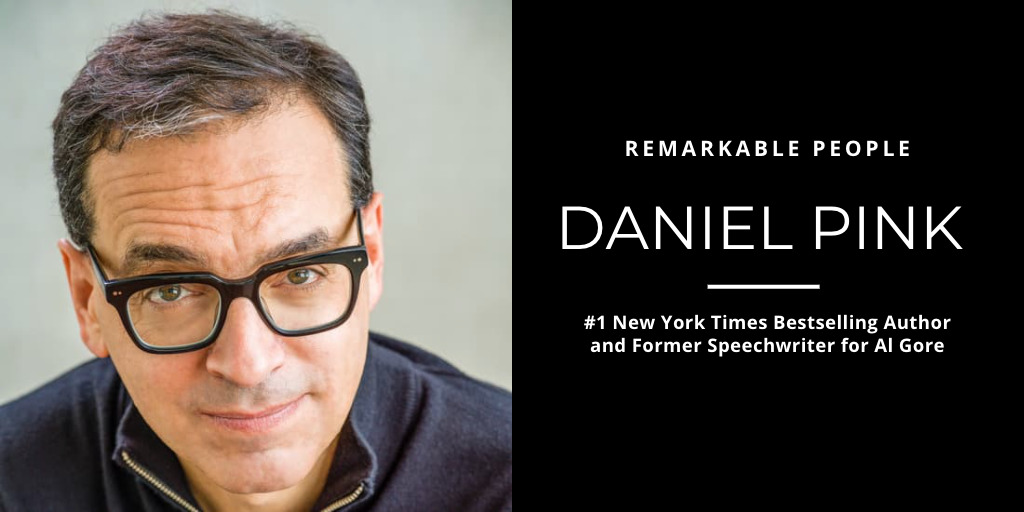

Our guest today is Daniel Pink.

He is a remarkable person who has changed the way many business people think, and how companies operate.

He’s the author of multiple award-winning books, and millions of copies have been sold of these books. His titles include When, A Whole New Mind, and his most recent, The Power of Regret.

Daniel worked in several positions in politics and government, including Al Gore’s speechwriter, and the host and co-executive producer for the National Geographic series Crowd Control.

He’s been a business columnist for The Sunday Telegraph, and a contributing editor at WIRED and Fast Company.

Daniel received a BA from Northwestern University, where he was a Truman scholar, and also received honorary doctorates from Georgetown University, the Pratt Institute, the Ringling College of Art and Design, the University of Indianapolis, and Westfield State University.

You may have seen him on TV and radio networks, including NPR, PBS, ABC, and CNN.

His articles and essays have been featured in numerous publications, such as The New York Times, Harvard Business Review, and The New Republic.

Enjoy this interview with the remarkable Daniel Pink!

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

I’ve started a community for Remarkable People. Join us here: https://bit.ly/RemarkablePeopleCircle

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with the remarkable Daniel Pink:

Guy Kawasaki:

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People.

Our guest today is Daniel Pink.

He is the remarkable person who has changed the way many business people think, and how companies operate.

He's the author of multiple award-winning books, and millions of copies have been sold of these books. His titles include When, A Whole New Mind, and his most recent, The Power of Regret.

Daniel worked in several positions in politics and government, including Al Gore's speech writer, and the host and co-executive producer for the National Geographic series Crowd Control.

He's been a business columnist for The Sunday Telegraph, and a contributing editor at WIRED and Fast Company.

Daniel received a BA from Northwestern University, where he was a Truman scholar, and also received honorary doctorates from Georgetown University, the Pratt Institute, the Ringling College of Art and Design, the University of Indianapolis, and Westfield State University.

You may have seen him on TV and radio networks, including NPR, PBS, ABC, and CNN.

His articles and essays have been featured in numerous publications, such as The New York Times, Harvard Business Review and The New Republic.

I'm Guy Kawasaki. This is Remarkable People. And now, let's learn from the remarkable Daniel Pink.

I stole a concept from you, inadvertently, called MAP: mastery, autonomy, and purpose. And I put that in my book. And after the book was published, I realized that I stole it from you, and I gave you no credit for that. And so I reached out to you and I said, "Daniel, I stole this from you. I didn't give you credit. I completely forgot, and I just want to admit it up front." And you said to me ... do you even remember this story?

Daniel Pink:

A little bit. I don't ... what did I say? I hope it was something gentle.

Guy Kawasaki:

No, no, it was very good. That's why I'm telling you the story. So you said to me, "Guy, I know you stole it from me, and I figured that eventually you'd figure that out and you'd correct it." And that's my favorite Daniel Pink story.

Daniel Pink:

Did you correct it? I don't even remember how this resolved itself.

Guy Kawasaki:

I corrected it in a future version-

Daniel Pink:

Okay, so, everybody wins.

Guy Kawasaki:

Everybody wins, but you took the high road, you gave me the benefit of the doubt, you showed such class and understanding and empathy that I was just blown away. Anyway, that's my Daniel Pink story.

Daniel Pink:

All right, I appreciate that. I'm glad you didn't bring up the story of the time that I hired a lawyer to go after another guy who massively plagiarized me.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh.

Daniel Pink:

There was this one guy who basically wrote a book, and I would say he essentially reprinted ten newspaper columns that I had written eight years earlier.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Daniel Pink:

And the only reason I heard about it was that some readers said, "Wait a second, didn't you say something like this?" But I know that you're a good dude. And since, we've run into each other over the years, I knew that there was no nefarious intent. Now we're talking together on your famous podcast, so everybody wins.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah, that's right. And you're about to release another book, so I hope this will help you.

But Daniel, you've been so prolific that we're going to spend a few minutes with your other things too. Okay?

Daniel Pink:

Okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

But first, what I find maybe the most remarkable part of your remarkable career is that, as far as I can tell, you started in politics. And you worked for Robert Reich and Al Gore, and then you became a free agent.

And yet, you're writing these great management books. I understand if you're Jack Welch and you ran GE, so you have all these stories and lessons and all this knowledge, but how did you do that with your career path to write such great books?

Daniel Pink:

Thank you for the premise of your question. I won't be a jerk and argue with the premise of your question, but thank you for that.

So I think you make a really interesting point about books. And the point is this, whenever I read a book, a nonfiction book, and someone is offering me insight or advice, you have to ask the question of, “How do you know?”

It is a theory of knowledge question. It is. I'm going to use a fifty-cent word on your show, Guy. It is an epistemological question. All right? How do you know?

And so when Jack Welch, may rest in peace, gives management advice, you say, "Oh, well. Jack Welsh knows because he ran GE for twenty years." All right. For me, if you have to ask the question, how do you know, the way that I know or the way that I try to be more right than wrong is I do a massive amount of research.

So for that book, Free Agent Nation, I spent over a year traveling around the country, interviewing hundreds and hundreds of people who had decided to work for themselves. That's how I knew.

When I wrote a book about motivation, I went back and looked at fifty years of academic research on what scientists say about human motivation. That's how I knew.

When I wrote a book about timing, I had to enlist other people, because there was so much material. I looked back at something like 700 studies across twenty-five different disciplines about what we knew about timing.

And now for this latest book about regret. How do I know? Among the things that I did is I went and I collected nearly 17,000 regrets from people in 105 countries.

So you're exactly right. If I just sat in this office where I'm talking to you, Guy, and started saying stuff-

Guy Kawasaki:

Like me.

Daniel Pink:

No, I disagree with that.

Because you worked at Apple, and you're an investor, and you have done all kinds of things with starters. That's how you know. But I think it's a really important question. And so my how do I know comes from doing the really painful, sometimes tedious work of grinding out the research.

Guy Kawasaki:

I might make the case, let's take the two extremes here.

So there's Jack Welch and Daniel Pink. So Jack Welch writes from a first person experience of what he did at General Electric. But Daniel Pink has looked at hundreds of sources of information, so arguably, Daniel Pink has a more scientific, objective, controlled, et cetera, et cetera, dataset than Jack Welch, one person, this is what happened to me.

Maybe he's a unicorn who farted pixie dust, and he's the only person who could do it this way.

Daniel Pink:

I'll tell you, that's a way to look at it. I'll give you another way to look at it from the reader's perspective.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay.

Daniel Pink:

This is how I operate as a reader. So I don't read a Guy Kawasaki book and say, "Oh my God, that's all there is I need to know. If I follow Guy, my life is going to be full of bliss and I'm going to lead a wonderful life."

No. What I do is I read a Guy Kawasaki book and say, "Oh, interesting. I like the way he did that. I don't agree with him on that. That's a really good point. I'm going to take that." Then, let's go back to Jack Welch or another, Bob Iger, or something like that. I might read that and say, "Okay, there's one thing that he did that's kind of cool. I'm going to borrow that."

Then I'm going to read a Daniel Pink book and I'm going to say, "Okay, Pink said these two things. I'm going to take that." And that's how you fashion understanding as a reader. You don't follow one person only.

You actually synthesize other people's ideas, take what works for you, and take what doesn't. And so I don't expect anybody who reads any of my books to follow me over a cliff. They'd be nuts if they did that.

But what I hope that they do is they read it and say, "Huh, that's really interesting. I never thought about it that way. I got these three insights, and I got these two things to do. That's awesome. What a great deal for twenty-two-dollars in hard cover."

Guy Kawasaki:

I think that many people do follow, especially self-help gurus, off the cliff, but that's a ... we don't need to go there.

Daniel Pink:

I think when you start thinking about going off the cliff, that's the problem. But I mean, seriously, I think it's really important that we, as readers, fashion our own understanding of the world by first bringing into bear all of other people's understanding and experiences.

So I'm not going to sleep on first person accounts of experiences, they can be really instructive. But I wouldn't base my own decisions on only that first person account. I would want something bigger and more contextual.

Guy Kawasaki:

I just interviewed John List from the University of Chicago.

Daniel Pink:

One of the great economists of our time.

Guy Kawasaki:

Exactly. And I asked him this question, which is, “How much of what we believe is based on undergraduate students trying to get credit by being subjects?” And he said “More than you think.”

Daniel Pink:

But it's interesting you say that, because that's a big problem. In fact, there's a guy at Harvard, Joe Henrich who has written this idea of WEIRD, W-E-I-R-D.

So Western Educated, Industrialized, something R, something D, whereas basically, most of the research in psychological science has been conducted, not only on undergraduates, but basically white well-educated Westerners.

And we're making claims, and that's something I think about a lot. This is one reason I went out in this latest book to gather my own research, and didn't rely exclusively on the existing academic research in regret. Because again, to go back to our epistemological question at the top of the show, how do you know? And I wanted to try to find that out by collecting all these regrets from all over the world.

Guy Kawasaki:

I like that on your website, you can click on a country and get regrets from that country. That's what you're talking about, right?

Daniel Pink:

Yeah, it's really amazing what we did. I was astonished. With almost no publicity, basically almost no promotion at all, literally, you have 105 countries, and we have only two other languages besides English. We have it up in Spanish, and we have it up in Chinese. But we have submissions in French, we have submissions in Portuguese.

And again, from all over the world, six continents and so forth, of people saying, "Hey, Dan. This is what I regret." And for this book, The Power of Regret, that's what became the really important source material for this.

Guy Kawasaki:

We're going to come back to regret, but I just enjoy so much and have applied so much of your work to my life and career, that I want to give my listener an exposure to the breath of your wisdom. Is that a softball or what?

So the way I would like to do this is, I'm going to pick a few books, and I want you to just give us the gist of those books. Hopefully, then people will go onto read the whole thing.

Daniel Pink:

This is fantastic. I feel like I'm on a game show here. This is awesome.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. So in the category of motivation, for 150 dollars, what's the gist of Drive?

Daniel Pink:

The gist of Drive is a book, again, where I went back and asked this question, What does motivate us?” And to answer that question, I didn't say what motivates me. I said, What does science tell us about this?”

It's tells us a lot of things. It tells us that human beings have a lot of drives. We eat when we're hungry, we drink, when we're thirsty. That's a drive. We respond to rewards and punishments in our environment, in many cases. But we also have other drives.

We do things because we like them. We do things because they bring us meaning. We do things because it's the right thing to do. And that other drive that third drive, I think, has been neglected by business.

Equally important, and I'll give you the ultimate big idea in that book, which is this. There is a certain kind of motivator that we use in organizations, psychologists call it a ‘controlling contingent motivator’. I like to call it an “if then” reward, as in, if you do this, then you get that.

Fifty years of science tells us that ‘if then’ rewards are great for simple tasks and short time horizons, but they don't work very well for complex tasks with long time horizons. And yet, organizations use them for everything rather than the area where they work.

And if you really want to have a sustained motivation in organizations, what you want to do, is you want to pay people very well, and then you want to offer them a measure of autonomy, some self-direction, some sovereignty over what they do. You want to offer them mastery, which is the chance to make progress and get better at something that matters.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now we figured out motivation. Now, how do we sell?

Daniel Pink:

Selling? So I wrote a book called To Sell is Human, because I felt like we didn't take sales seriously enough. I think a lot of people who do what you and I do, Guy, which is write books about this stuff, sometimes look down on sales. And I thought that's a colossal mistake.

So two animating ideas in that book, one, like it or not, we're all in sales. So whether you have sales in your job title or not, we're selling all the time.

And again, how do I know? I did a pretty interesting survey where I asked people how they spent their time. And we found that people are spending, on average, about 40 percent of their time convincing, persuading, influencing, cajoling, other people. Selling, essentially. So we're all in sales now.

The second big idea in that book is that sales is not selling anything. Your idea, yourself, your product, your service has changed more in the last fifteen years than the previous 1,500. We used to have a sales environment that was defined by information asymmetry. That is, the seller always had more information than the buyer. That's how it was for almost all of human commerce.

And then, literally a decade ago, a decade and a half ago, that all changed. We don't live in a world of information asymmetry today. We live in a world of information parody. And in a world of information asymmetry is a world of buyer beware.

That's why we have buyer beware as a principle, because sellers have an advantage because of information. But now, we're in a world of seller beware, where sellers cannot take the low road.

So we used to be in this world where buyers had not much information, not many choices, and no way to talk back. That's most of commerce in our history. Now, we're in this world where buyers have lots of choices, lots of information, and equally important, all kinds of ways to talk back.

That's a world of seller beware. And so this book looks at, “How do you survive in a world of seller beware?” And once again, we look to the social science for clues about how to do it effectively and ethically.

Guy Kawasaki:

And what's the gist of how to sell in this new time?

Daniel Pink:

There are the new ABCs. We know about the old ABCs, made famous by the David Mamet play and movie, Always Be Closing, ABC. A, Always, B, Be, C, Closings. Tough, predatory, that's how you do it in information asymmetry, where you have an edge as a seller. Always be closing. That approach, it's a bad idea.

What the new approach tells us is a new set of ABCs. Again, total luck that they started with ABC, just to be transparent here, is that what does the social science tell us about what you really need to do to be effective in this new terrain? And the new ABCs are A, attunement. That is, can you get out of your own head into someone else's head, see their perspective? That's really important.

Can you take someone else's perspective, see things from their point of view? We have very little power to force people to do stuff inside of organizations and in the market. So you need the opposite ability, which is, can you get out of your own head and see things from someone else's point of view? That's attunement.

B, buoyancy, I got as a concept from a salesperson who said, "Dan, you don't understand how tough my job is." He said, "Every day, I face," this is his phrase, "an ocean of rejection." An ocean of rejection. And that's what it is. If we're persuading and selling all the time, we face an ocean of rejection.

And so buoyancy is, how do you stay afloat in that ocean of rejection? There's some things that we can do to deal with rejection. None of us like rejection. A lot of us, as a consequence of that, either are debilitated by it, or we shy away from it. That's a mistake. The key is to stay afloat in the ocean of rejection.

And finally, our C, clarity, has two dimensions. One, go back to information. It used to be in the old days that you were an expert, that you had an edge if you had access to information that no one else had. So in some ways, the nature of expertise was that you had privileged access to information.

But now everybody has the information, so you can't have privileged access. And there's so much information out there, you need to be able to curate information, make sense of information, separate out the signal from the noise and information. So we got to move from information access to information curation.

And finally, and I think this is one of the most intriguing things, is that we used to be in a world of problem solving. So that you had salespeople who would say, "Ah, I'm not really in sales, I'm a problem solver." And that's cool.

It's just that today, if your customer prospect knows exactly what their problem is, they don't need you. So when do they need you more? They need you when they're wrong about their problem, or they don't know what their problem is. And so the skill shifted from the skill of problem solving to the skill of problem finding. Can you identify hidden problems, surface latent problems?

So attunement, buoyancy and clarity are the new ABCs of selling in this world where we're all in sales, but we're doing it in a completely remade landscape.

Guy Kawasaki:

I wish people would internalize and understand this concept that if your lips are moving today, you are selling. It might be to get an aisle seat, it might be to get an upgrade, it might be to get an extra side of salad dressing, but you are selling. I don't what people are thinking. Yeah.

Daniel Pink:

Exactly, exactly. And I think part of it is that a lot of smarty pants, people look down on sales, and I think that's a mistake. And one of the things that got me into this particular topic was that writing about business for all these years, I interviewed a lot of sales people for other work that I did. And there's this sort of stereotype we have about sales people, and none of these people were like it. They were really smart. They were really smart, they were among the savviest people there. They were curious, they had both very strong intellect and strong emotional intelligence.

And I'm like, "Wait a second. Why do we have this stereotype when the people I'm meeting who are in sales are actually really astute?" And I think it's because sales has changed so much.

I'm convinced, and I've said this before, that B2B sales today is essentially management consulting. You shouldn't even call it sales. It's essentially management detail.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, tell me about Perfect Timing.

Daniel Pink:

So you'll appreciate this. I'll give you the high concept pitch for this book. The high concept pitch was that there were lots of ‘how to’ books, but there hasn't been a ‘when to’ book.

Guy Kawasaki:

Mm-hmm (affirmative).

Daniel Pink:

So this was the first ‘when to’ book. And so I looked at, as I mentioned earlier, about 700 plus studies in timing. And what's interesting about these is that you had all this research being done across many different disciplines, you had research being done in psychology, and in sociology, and in economics on how time of day affects us, how sequence affects us.

But you also had this research being done in anthropology, and in linguistics, and in cognitive science, and in microbiology, and a whole field called chronobiology, and in epidemiology, and in endocrinology, and in various kinds of other medical fields. And what was weird is that you had these scholars who were asking literally at sometimes the exact same question, but weren't talking to each other.

And so it took the, basically, a non-expert, it took a non-specialist to take three steps back and say, "Wait a second. What the economists are saying is very similar to what the microbiologists are saying."

And so what this research yields is, how does time of day affect what we do and why are breaks more important than we realize? So that's daily timing. And one of the things that comes out very strongly in daily timing is that time of day affects our brain power a lot more than we realize, and we don't schedule around that.

We basically assume that our brain power remains constant over the course of a day, and that's wrong. That we can actually use this science to make better decisions about our daily timing, but some really incredible stuff about breaks. It totally changed my view of taking breaks.

And then also episodic timing, so how do beginnings affect us? How do midpoints affect us? How do endings affect us? How do groups synchronize in time? How does the very way we think about time affect our behavior? So it's a wide ranging look at the science of timing and how we can enlist it to do better.

Guy Kawasaki:

And when is my peak brain power?

Daniel Pink:

We can figure this out. Let's figure this out. We'll do it here.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay.

Daniel Pink:

Let's start with something called a chronotype. A chronotype is essentially our propensity.

Do we naturally wake up late and go to sleep late? Or do we naturally wake up early and go to sleep early? So what do you think you are?

We can test this in a moment.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay.

Daniel Pink:

But what's your instinct on you? Wake up early and go to sleep early, wake up late and go to sleep late, or somewhere in between?

Guy Kawasaki:

I wake up at about 4:00am to 4:30am. I try to force myself to go back to sleep, and so I'm a early riser. I go to bed or around 9:00pm, 10:00pm.

Daniel Pink:

So it sounds like you're more of a lark than an owl. So here's what we know about the distribution in the population. About 15 percent of us are very strong morning people, larks.

About 20 percent, 25 percent of us are very strong evening people, owls.

And about two thirds of us are in the middle. I'm more in the middle.

So here's what we know. So most of us move through the day in three stages: a peak, a trough, a recovery. And certainly, everybody who's not a night owl moves through the day pretty much in those stages. Peak early in the day, trough in the middle of the day, recovery later in the day. And so what we know about that peak, which for you is going to be early in the day, that's when you are most vigilant, Guy.

So what does it mean to be vigilant? Vigilance means you're able to bat away distractions. So that's the time that you should be doing analytic work, heads down, focus work; writing, analyzing data, going over a strategy.

So instead of starting the day, as many of us do, answering email or doing that kind of BS, we should be focused in on analytic work that requires vigilance. We do that better, 80 percent of us do that better early in the day, rather than later in the day.

During the trough, the early to midafternoon, terrible time of day. Huge decrements in performance for almost everybody. The top takeaway from that book, When, is that people should not go to the hospital if they can avoid it in the afternoon.

Guy Kawasaki:

Because the doctors are troughing?

Daniel Pink:

Oh, yeah. No, the numbers are incredible here. I'm not joking around. If you look at ... I'm not kidding on this one.

Anesthesia errors, four times more likely at 9:00am than at 3:00pm. Colonoscopies, doctors find twice as many polyps in morning exams as they do in afternoon exams, on the exact same population.

Hand washing in hospitals deteriorates significantly in the afternoon. Doctors are much more likely to prescribe unnecessary antibiotics, and opioids too, there's a recent paper on that, in afternoon appointments versus morning appointments.

So in my family, I'm not joking, if you have to do a serious medical procedure, you do not do it in the afternoon in my family. You do it in the morning. I'm serious.

No, here's the thing. If one of my kids gets hit by a bus, God forbid, and it's three o'clock in the afternoon, I'm not going to say, "You just got hit by a bus, you got to wait until the morning to go into the hospital." But if you have any discretion over it, you don't go to the hospital in the afternoon if you can avoid it. I'm dead serious about that.

Now, some hospitals have done a good job of mitigating that through checklists, and breaks, and things like that. But still, the numbers are pretty clear that going to the hospital in the afternoon is a bad-

Guy Kawasaki:

If you're going to the mechanic, you should take your car in at 7:30am in the morning, not at 1:00pm.

Daniel Pink:

It depends on when they're going to work on it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Daniel Pink:

There is something to be said of that. And here's the thing, this is the great revelation of that research, which is that we think that all times of day are created equal, but our performance differs over time.

Now, the other thing that's interesting here, and now around this out, is that for someone like you a lark, pretty hardcore lark, in the late afternoon or early evening, your mood goes up, but your vigilance does not, and that's a really interesting combination.

So that makes us better at solving other kinds of problems, what psychologists call insight problems, are problems that don't bend to mathematical logic, that require more iterative thinking, brainstorming, divergent thinking.

And there's some really interesting experimental evidence, that if you give someone like you, like Guy, the hardcore Lark, an analytic problem in the morning, you're more likely to get it right than you are in the afternoon.

But if we give you an insight problem, a problem that requires divergent thinking, sort of non-obvious solutions, you're more likely to get it wrong in the morning and right in the afternoon.

And so one of the keys here is you have to do the right work at the right time, and there's a pretty simple recipe for that. Basically, do your analytic work in the peak, your administrative work in the trough, and your insight work in the recovery. And I've changed my schedule to try to do that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Really? So if I may translate, does this mean I should do email in the trough?

Daniel Pink:

Yes, most email isn't worth it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Exactly.

Daniel Pink:

You should do your administrative stuff. You should do stuff that doesn't require massive analytic thinking or creativity. And unfortunately, that's part of our day. I have, right now, looking at my email client here, because I was actually doing analytic work all morning, I've got ... what is it here?

So I've got seventy-three unanswered emails here. That's cool, because I had some important analytic work to do this morning, and I wanted to focus on that rather than do the bullshit email.

Guy Kawasaki:

So maybe we should schedule our email clients to check the first time at noon.

Daniel Pink:

You could do that. I'll admit ... I shouldn't reveal this on a broadcast that tens of millions of people are listening to-

Guy Kawasaki:

I wish.

Daniel Pink:

... but I have been known to basically answer emails, but have them go out a few hours later, in part because I didn't want to receive an email right away during that period.

So let's say that I wake up in the morning, I see an email and I can answer it in ten seconds. I will sometimes set it to go for one in the afternoon, because I don't want someone emailing me in the morning during my good time, because I might be tempted to deal with it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Oh. I also think, as a matter of courtesy, I have now instituted a practice where all the email that I respond to on the weekends, I schedule to not go until Monday morning.

So maybe, I should make it Monday at lunch.

Daniel Pink:

It could be. I sometimes will do that. And sometimes, I will put in the subject line, "No need to deal with this until Monday."

Guy Kawasaki:

Next book. And this is the last book I'm going to ask you before we get to regret.

Daniel Pink:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

So, Free Agent Nation. So today, in a pandemic world, aren't we all in a sense free agents at this point?

Daniel Pink:

Well, yes we are, in some ways. You mentioned earlier, Guy, that I worked in politics. There's some politicians who they've said, he or she are ahead of the voters. And I think that was the case where, on that book, Free Agent Nation, I was a little bit ahead of the voters.

Because what I argued in that book is that more and more of us were going to be either working for ourselves, either literally, or even more, our attachments to large organizations were going to weaken and weaken. And we were going to be responsible to bear the risk and navigate our own way.

And I even said in that book that the division between work and home is going to blur, and that you're going to have lots of people working at home. And a lot of people, including people like Jack Welch have said, "Oh, no. That'll never happen. You can't trust people to work at home."

And then in March of 2020, hundreds of millions of people around the world did it in four days, and it worked okay. That's a long-winded way of answering your question, yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

And you think there really is a great resignation happening?

Daniel Pink:

Maybe. We might be making too big of a deal of that. And if you look at some of the data, what some of it suggests is that people at the older side of the labor market are actually retiring-

Guy Kawasaki:

Right.

Daniel Pink:

... and exiting the labor market altogether. And that younger workers are, because the labor market is tighter, feeling a little bit more empowered to bop along. But I do think there is something.

The other thing about the great resignation, I think at the lower end of the labor market, so the less skilled end of the labor market, is that people are realizing that a lot of these jobs were just terrible jobs.

Terrible jobs, and they were being treated in terrible ways. And they essentially said, "I don't want to deal with that anymore." And so this is one reason I think why you have right now, and as we're talking now, an incredible boom in self-employment. Because I think some people are saying, "Listen, I cannot make much money and be treated like crap and not have any job security, or I can go out on my own and not have any job security, but actually have some self-respect." And they said, "I'll take that second deal."

Guy Kawasaki:

Sure, sure. So you were ahead of your time.

Daniel Pink:

Maybe.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now that everybody's listening, it's, "Oh my God, there's so many good ideas coming out of this guy. I got to go get all his books." But now we're talking about the book, and the book is called The Power of Regret.

And my first question is, what kind of person says, "I have no regrets"?

Daniel Pink:

Such a good question. What kind of person says that? A five year old, a person with brain damage, or a sociopath. Those are the only people who have no regrets, and I mean that literally.

Once again, I went back and looked at the research, and what the research tells us is that everybody has regrets. Every functioning human being has regrets. They make us human.

And truly, I'm not joking around, Guy, the only people without regrets are little kids whose brains haven't developed yet. We develop our capacity for regret around age seven or eight. People with severe brain injuries or brain diseases, so there are certain kinds of lesions that people will develop that will prevent them from experiencing regret, people with Huntington's disease, and Parkinson's disease often have difficulty dealing with regret. And then sociopaths.

This idea that we celebrate, especially here in America, "No regrets," is complete nonsense. Having no regrets is a sign of a grave problem.

Guy Kawasaki:

I don't know if you want to answer this question. You can take the fifth if you want, but do you think that ten, twenty years from now, if they're still alive, do you think people like Rudy Giuliani, Joe Manchin, Ron DeSantis, Mitch McConnell will ever look back with regret about what they're doing now?

Daniel Pink:

That's an interesting question, and I don't know. And I think that those four people are very differently situated, or somewhat differently situated. And I think there's a chance that they will and let me give you an analogy to that.

This country, there's mythology that America has been calm and together, and when in fact, our whole history, it's been roiling for a long time. Most periods in American history, there's been stuff going on, and been dissension and so forth.

And if you look at some of the people who in the 1960s voted against some of the civil initiatives, including the father of my old boss, Al Gore Sr., who was a senator from Tennessee, many of those politicians who voted against civil rights, many of them who voted against Medicare, which is now sacrosanct, barely passed in the mid 1960s.

And so a lot of people who look back on those actually do express some regrets. So maybe people will regret that they didn't do their part to preserve our democracy.

And maybe some of us, like you and me, will regret that we spent time making podcasts and writing books rather than standing up for our democracy, which is, to my mind, in peril right now.

Guy Kawasaki:

That last part of statement, I completely and utterly agree. And I am just appalled that there's a group of influencers who when you ask them about political issues, they say, "I'm not political. I'm not discussing that. I'm an influencer in fashion, or tech, or something. That's not my wheelhouse, that's not my responsibility." And I think that is a total cop out.

Daniel Pink:

No, it's tough, because here's the thing, I don't talk a lot about politics. And certainly on social media, that's the worst possible forum for doing that.

No one has ever changed their mind or learned anything arguing about politics on social media. Yeah, but it is an interesting point about the sorts of things that we regret. And one of the things that comes out in the research that I did was that one of the big categories of regret that people have were moral regrets, and also regrets about not speaking up.

And so I wonder if some of us, given the times that we Americans are living in now, might ten years from now, twenty years from now, look back and say, "Oh wow. I should have spoken up. I should have done more."

Guy Kawasaki:

I had an a-ha moment, in about 2016, I was over in Germany and I met with some people. They were about forty, forty-five-years old. I had dinner with two or three friends. And they said to me, "Guy, to this day, we question our grandparents, how could they let Nazi Germany happen? How could they let Adolf Hitler come to power?"

And then they said, "Guy, it's 1930 for you in America, so do you want your grandchildren to wonder if you resisted?" Holy shit. I felt so convicted, I went back, and I was all in on politics. Anyway, that's my story.

Daniel Pink:

Yeah, this is a great and fascinating issue. Let's take straight white men born in America, like me, I think a lot of us would look back and say, if we were around in 1850s, we would've been totally against slavery. "I would've been helping Harriet Tubman."

And I don't know if that's the case. My grandparents, my ancestors were not in the United States at that time, but had they been, I don't know. It's a fascinating question.

I think that there are things happening now, leaving aside the political stuff, that their grandchildren now might look back and say, "Oh my God, my grandfather, or great-grandfather, he was deplorable, he was an idiot. The whole planet's burning up, and he didn't do a goddamn thing." Or, “Look at the way we treat animals”, or, "Wait a second, they were driving around these cars that were burning fossil fuel for a hundred years and destroying the planet, and everyone said, 'Oh, that's all right. That's cool. Let's build some more...'?"

So I think that there are all kinds of things. We might look back and say, "Wait a second, how could he live in Washington, D.C. and live with himself?" On a day like today, a Monday in January, when if I walk eight blocks from my house, I might walk by an unhoused person and not do anything.

So it's a very interesting moral question. And so I don't think that any of us are paragons of virtue here.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yep, we certainly went down a path there.

Daniel Pink:

So on that happy note.

Guy Kawasaki:

So just give us the gist of this book.

Daniel Pink:

So this book looks at regret, which is our most misunderstood emotion. And as we were talking about earlier, we have this ridiculous notion that the way to leave life is to have no regrets, and that's wrong. All of us have regrets, they make us human.

But what we don't know, what we haven't realized, and again, we can look at the science on this, is that regret not only makes this human, but it also makes us better.

If we deal with our regrets properly, they make us better, they can help us improve our decision making, they can boost our performance on a whole array of tasks, and they can deepen our sense of meaning. And so, how we reckon with our regrets is incredibly important.

So what we should be doing is not ignoring our regrets, and not wallow in our regrets, but using our regrets as signals to do better. So that's one big idea in the book.

The other thing is that, as we mentioned earlier, I went back and looked at, I collected over 16,000 regrets from around the world. And what I realized is that the way that scholars were understanding regret was wrong. We were looking at what people regretted based on the domains of their life. This is a family regret, this is a career regret, this is a romance regret.

And what I found looking at these 16,000 regrets from around the world is that beneath those domains of life, there was a deep structure of regret that around the world, and it's pretty amazing, overwhelmingly, people regret the same four things, over and over.

And these four core regrets are fascinating because they operate as a photographic negative of the good life. That is, if we understand what people regret the most, we understand what they value the most. And so this negative emotion of regret gives us a path to a good life.

Guy Kawasaki:

What are the four?

Daniel Pink:

Foundation regrets, people around the world regret not exercising enough, not taking care of their bodies, not studying hard enough in school, not saving money.

So things that where you didn't do the work, and as a consequence, your platform is a little wobbly.

You'll appreciate this next one, boldness regrets. Overwhelmingly, in my research and in other research, people regret inactions way more than actions. They regret what they didn't do way more than what they did do. And so these boldness regrets are all over the place.

People regret not starting a business, staying in a lackluster job, and not starting a business. I got huge numbers of people around the world regret not asking someone else on a date. It's, literally, hundreds of regrets where they say, "Oh, I met this man or woman X years ago, and I wanted to ask her out, or him out, and I didn't." Lots of regrets about speaking up. So boldness regrets are, if only I'd taken the chance.

Moral regrets, fascinating category. I have hundreds of people, once again, who regret bullying kids at school when they were younger. I have sixty-year-olds, when they're sixty, seventy, who regret bullying kids. I had a woman who I interviewed, who broke into tears, recounting the story of bullying a kid when she was eight years old, and she's in her fifties.

So we regret not doing the thing, which is heartening, in a way.

And then finally, our connection regrets. Connection regrets are regrets where there was a relationship, or there should have been a relationship, and somehow, it drifted apart.

Among the things I discovered in looking at these is that the way our relationships come apart, typically, is not dramatic. That is, we think that relationships come apart by some kind of blow out fight, and that's rarely the case. A lot of times, they just drift, and drift. And what happens is that nobody wants to reach out.

They say, "Oh, I would reach out, but it's going to feel really awkward, and the other side's not going to care."

And what the research tells us is that it doesn't feel awkward, and that people do care. And that these connections to other people, children, or spouses, or siblings, or friends are so important in people's lives. These connection regrets are the biggest category.

And so what these regrets show is, “What do we want out of life?” We want a stable platform, we want some stability, we want a chance to do something big and bold, and take a chance, and lead a psychologically rich life, we want to do the right thing, and we want to have close connections to others.

That's what life is about, and everything else doesn't matter. And so in a weird way, this negative emotion, regret, actually tells us what makes life worth living.

Guy Kawasaki:

And do you believe by learning this, or listening to other people's regrets, that people can learn to optimize their lives?

Daniel Pink:

Absolutely.

Guy Kawasaki:

If I tell my son, "Oh, I regret not studying harder in high school," do you think my son is going to say, "Oh, yeah. Dad's right. I'm going to study harder"?

Daniel Pink:

Maybe. But I think there's a better chance of him studying harder than if you didn't say that.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay.

Daniel Pink:

You have to ask yourself, "Compared to what?" And so one of the things about our regrets is that some of the things we can do something about. We can repair them, we can undo them. But other times, especially as we get older, the best use of our regrets is to give advice to other people.

And for you, if that is a legitimate regret of yours, I'd rather have you offer that to your son, rather than not offer it to your son. I'm not saying it's some magic elixir that's going to change things, but it's better than doing nothing.

More important, what also the research tells us, is that when we disclose our regrets, disclosure itself is really important. It makes us feel better. So there's some interesting research showing that when we disclose our regrets, we feel better.

When we simply write them in a diary, we feel better. We live with the burden.

What's more, and this is where your son comes in. We sometimes think that if we reveal negative things about ourselves, particularly our regrets, people will like us less. Like, "I don't want to admit that I was an idiot. People are going to think less of me."

And what the research tells us is that's wrong. They actually think more of you if you reveal those kinds of things. So self-disclosure itself is valuable both internally and externally, and it's one of the most important ways that we reckon with our regrets.

Another one of my favorite ideas is what Tina Seelig, whom you might know at Stanford, calls a ‘Failure Resume’, that we should have a failure resume. That what we should do is that along with our resume, which is this list of all the incredible things we've done in our life, we should have a failure resume, and list all the screw ups, and setbacks, and flubs, and fuck ups in our life.

And I've done that. And then list those, but then the next step is to look at them and try to extract a lesson from them going forward.

And when I did this, when I did a failure resume, I realized that if I looked at a lot of my failures and setbacks, I was making the same two mistakes over and over again. And that helped me cure that mistake. In some ways, we've overdosed on positivity in America.

We think it's always important to be sunny and positive and optimistic, and it is important to do that sometimes. But these certain negative emotions, including our most prominent negative emotion of regret, give us clues, they give us information, they give us direction, they give us clarity about how to live better and work-

Guy Kawasaki:

And what divides regret from guilt?

Daniel Pink:

Oh, interesting. So, it depends. Some of these moral regrets are infused with some degree of guilt.

Guilt essentially means that we've wronged somebody else, we've violated some kind of moral code, so a lot of the moral regrets involve a measure of guilt. The boldness regrets are less about guilt.

There are some interesting distinctions here. So there's a difference between guilt and shame. So guilt is feeling bad about what you did, shame is, in some ways, feeling about bad about who you are.

Shame is debilitating, but guilt about particular actions is useful if you use that as a signal to do better the next time. There's also a difference between regret and disappointment. Though, one of the key elements of regret is that you have some control.

So for instance, I'm an NBA fan, and I live here in Washington. Against my better judgment, I'm a fan of our hometown team, the Washington Wizards. And so I'm disappointed when the Wizards don't win the NBA championship, but I can't regret that, because I had no of control over that.

But I might regret that I didn't go to a game this year with my son, because that's always fun and a great way to make connections. And I might regret that, because that's something I had-

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you think that the concept of regret, and the study of regret, and this analysis of regret is also an American phenomenon, that only we Americans have so many choices that we can express regret. Whereas if you're completely impoverished and barely making it and have no control over your life, what can you regret? You don't have any choice.

Daniel Pink:

I think that's a really interesting question. I tried to answer that in this, and this is why I got regrets from around the world. And my view of it is that, the answer is in some ways yes and no.

So here's some of the things that I saw in my own research, is that it turned out that people with the most education had the most career regrets. Now you say, "Well, wait a second. They have so many options."

Guy Kawasaki:

Right.

Daniel Pink:

That's exactly why they had more, because they had so many options. So it's a double-edged sword of opportunity. On the other hand, the people with the most education regrets were people who had some college, but had never graduated, because there was a kind of a thwarted opportunity there, so a lot of regret hinges on opportunity.

And so if we have this vast vista of opportunities, we actually have more chances of things to regret.

But if you think about connection regrets, there's very little correlation between income or anything like that, because everybody, whether you're rich or poor, want to connect with other people.

And when you think about things like foundation regrets, it gets a little complicated, because if I say, "I really regret that I didn't work hard enough and that I didn't do well in college," is that because you were lazy, or is that because you went to a crappy secondary school that didn't prepare you for the rigors of university education? And so it's not entirely your fault.

But one of the things that comes out in the research on regret at its core that you're identifying, is that our lives are a mix of opportunity and obligation. We want opportunity and obligation. That's what makes a good life. So a life of only opportunity and no obligation, that's hollow.

A life of obligation and no opportunity, which is true for some people, that's very crimped. But a life where you have both obligation and opportunity, that's a good life. And I think that's one of the things that regret teaches us.

Guy Kawasaki:

You think we should add regret to the hierarchy of needs of Mr. Maslow?

Daniel Pink:

Here's the thing. We're coming back, this is the Guy Kawasaki theory of knowledge podcast, because we're coming back to another epistemological question here, which is how-

Guy Kawasaki:

I don't even know what that word means. I'll look it up at this.

Daniel Pink:

Just keep saying, I don't know what it means either, I just like to say it. But it's an important question. How do you know? How did Maslow know? And Maslow, whom I admire, he just kind of said stuff. He was basically a philosopher.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Daniel Pink:

He didn't do experiments in the way that many modern social scientists do. He was like a philosopher, and he just asserted this hierarchy of needs. And it's a very interesting idea, it gives us a common way to frame things, but I don't think it's that super empirically sound.

What's interesting, very good instance here, is that when I thought about these foundation regrets, I started thinking of them as a hierarchy. And then I realized, they're not, that it's not a building, it's more of a soup. They all go together.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, a slight aside here, because I'm interested in your technique. So when you say you researched 700 studies and all this kind of stuff, what are you using to do this? Are you a member of every scientific journal organization? Where do you go? Do you go to the American Psychology Journal, and you just type in regret, and you find all the keyword searches?

Daniel Pink:

I'm glad you asked. So I do subscribe to many journals, but one of the great resources out there is Google-

Guy Kawasaki:

A-ha.

Daniel Pink:

... which is a massive database with these kinds of things, but this is why it takes me so long to write these books. And I'll talk to academics, "So I want to know about this topic, who should I read?"

And they're like, "Oh my God, you got to look at the papers of Tom Gilovich," and so I'll pull the papers out, who's a social psychologist at Cornell. And I'll read them through, and then I'll look at the footnotes, and I'll pull those, and I'll read some of those. And then essentially, you start falling in on yourself. But what I have, since I'm old school, is I do almost all of this on paper. So-

Guy Kawasaki:

What?

Daniel Pink:

Guy and I are talking via video call, but I'm pulling out ... this is what's known, in ancient times, I don't know if you remember these things, these kinds of folders. They're called Redwelds, they're these giant expandable folders. And I mean, just pulling out here, so I have these papers and I will print them out and read them on paper, and underline them, and make notes.

And that's why I only write a book every four years, because I'm here grinding through all that stuff. So you find one, that leads you to another, leads you to another, you call people and ask questions, you type notes. And you begin to start hearing the same things over and over again, and that's when you realize that you've hit the ceiling.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. Man, it's hard to write a book the way you do.

Daniel Pink:

Yeah, it's really hard. Listen, I'd rather be like Maslow and just sit in my office. What do you think? You're looking into my office. What do you think? You think in that corner over there, I'd just put on a smoking jacket and a pipe and think?

Guy Kawasaki:

And you write with a fountain pen. How hard could that be?

Daniel Pink:

Yeah, exactly. And I have assistants who go on and find quotes from Greek literature, and they scurry off and bring me a cup of tea. No, no, no, no, no. It's like anything, Guy. You know this better than anybody. Think about entrepreneurship. Is entrepreneurship this like, "Oh, wow. Here's what we do as an entrepreneur. I think great thoughts, and then riches fall from the sky"?

No. You try something, and it doesn't work. And then you feel like it's all going to go to hell, and then you try something else and you pull it back from the brink, and then you grind it out, and grind it out some more, and grind it out some more. And then a few things work, and a few things don't.

And I think that's like any enterprise. I think that's true for art, I think it's true for entrepreneurship, I think it's true for sports. Good stuff happens, you got to like the grind-

Guy Kawasaki:

Well-

Daniel Pink:

... in order to get good stuff done.

Guy Kawasaki:

And that's why Angela Duckworth gave you such a great blurb for this book. Right?

Daniel Pink:

Angela Duckworth, who brought that concept of grit there, which is it. It's passion and perseverance for things that matter to you. And that's what it is. But I don't it has anything to do with me, I think it has to do with anybody who's trying to do stuff. I think it's true for you, Guy.

What do you do? You show up, right?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yep.

Daniel Pink:

You show up. You show up and you do your work, and then you show up the next day and do your work, and you show up the next day and do your work.

Guy Kawasaki:

But some people say, or the saying is that showing up is 90 percent. I don't think that's true. I think showing up is about 10 percent-

And it's the grit. You got to keep showing up.

Daniel Pink:

Oh, yeah. Exactly, exactly, exactly. If I show up in my office and watch ESPN highlights for six hours, I'm not going to get a lot of work done. It's showing up and doing the work.

It's like what Julius Erving, the great hall of fame basketball player, Dr. J said, "Being a professional is doing what you love to do, even on the days you don't feel like doing it."

Guy Kawasaki:

Well-

Daniel Pink:

There are many days when it's, "Oh, crap. Here are twenty-six studies that I need to read." And a lot of them are poorly written, and half of them I don't understand. And I'm not sure any of them are going to pan out, but I show up and I do my work.

Guy Kawasaki:

The great philosopher.

Daniel Pink:

Again, this is what teachers do. Do you think teaching first grade is easy?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Daniel Pink:

Do you think teaching first grade is a sea of bliss all the time? No. You make a lesson plan, you show up. And on that day, you reach some kids, but lose other kids, and you deal with some kind of hassle you didn't expect. And what do you do as a first-grade teacher?

You show up the next day. What do you do as a professional athlete? You show up the next day. What do you do as a musician? You show up the next day and do your work. That's what it's all about, man. It's just, you show up and you do your work.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yep. I interviewed Mark Manson for this podcast. He's the guy, The Subtle Art of Not Giving a Fuck.

Daniel Pink:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

And one of my most favorite moments in this podcast was when he told me, "Guy, you've truly discovered what you love to do when it's a shit sandwich, and you love the shit sandwich." And I think editing a podcast is a shit sandwich, but I love that shit sandwich.

So it's all about finding the shit sandwich that you love.

Daniel Pink:

Yep, or that you can tolerate. I'll see you and raise you a little bit on this. This is one reason, Guy, why I hate the question that people ask is, "What's your passion?" I freaking hate that question.

Guy Kawasaki:

Idiocy.

Daniel Pink:

Yeah, because I'm a writer, I've been writing books for twenty years. And if you say to me, "Dan, is writing your passion?" I would say, "I don't know. Writing's really hard. And there's some days I hate it."

Guy Kawasaki:

Yep.

Daniel Pink:

Truly, there's some days I hate it, but it's what I do, and I can't help myself. I think that's one of the things that we can and help younger people understand is, get out of this very managed, social media, prettified view of what work and accomplishment is, and instead, focus on the process.

I'm a sports fan and I hate to analogize to sports for everything, but if you look at some of the very best athletes in any domain, they're also some of the hardest workers. They're the basketball players who, when everybody else is gone, are shooting 200 free throws after practice.

And Angela Duckworth really nailed that that ends up being one of the best predictors of being able to make a reasonable contribution is, “Are you willing to stay after practice for another hour and shoot 200 free throws?”

Guy Kawasaki:

Going back to your diatribe about writing, I heard two great quotes about writing. So one was, "The only thing worse than writing is not writing."

Daniel Pink:

Amen.

Guy Kawasaki:

And the second one is, "Writing is opening a vein and pouring your blood onto the page."

Daniel Pink:

That's exactly right.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's what it is.

Daniel Pink:

That exactly right. So I think it was Hemingway, something like that. Maybe it was not Hemingway. Yeah. Writing is easy, just open up a vein and bleed, and that's what it is.

But this is true for anything. It's like, I want a non-glorified, non-prettified, non-cosmetic view of what working and certain kinds of fields are like, because I think there's something actually really ennobling about that.

It's ennobling to see a great tennis player spend four hours a day hitting only back hands. That's how you become a great tennis player. Or some great violinist working only on one small movement of one piece in order to get it exactly right. That's how you do it.

Guy Kawasaki:

So we're over an hour already, but I want you to just drive it home for this book about regrets.

Daniel Pink:

Yes, sir.

Guy Kawasaki:

What's the takeaway? Why should people buy this book?

Daniel Pink:

They should buy this book because it offers a way for them to take their regrets, not as something to deny, and not as something to wallow in, but it's something they can use to lead a better life.

And you'll understand what they regret, what other people regret, and there is a process in the book, three step process, where you can take your existing regrets, extract a lesson from it, and use it to live better.

And, I also have something in the book called the ‘regret optimization principle’, which debunks Jeff Bezos's regret maximization principle. It's smarter, more science-based, and more helpful. So I think this book will help you see your life differently and live your life differently.

Guy Kawasaki:

There you go. And I will tell you that one of my regrets in life was stealing MAP from you, but I recovered from that.

Daniel Pink:

You undid it.

Guy Kawasaki:

I undid it.

Daniel Pink:

One of the things is that with regrets.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes.

Daniel Pink:

And so it's a regrets of action, one of the things we do with regrets of action is we can undo them. We can make amends.

Guy Kawasaki:

There you go.

Daniel Pink:

And you did, and here we are.

Guy Kawasaki:

Daniel Pink, you are the man. Thank you so much. I hope everybody buys every book we mentioned today.

There you have it, Daniel Pink. His stuff is good enough to steal. And believe me, not everything is good enough to steal. So I hope you learned about motivation, why you're always selling, what to do about your regrets, and finally, what time to get a colonoscopy.

You heard it all here. I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People.

My thanks to Peg Fitzpatrick, Jeff Sieh, Shannon Hernandez, Alexis Nishimura, Luis Magaña, and the drop-in queen, Madisun Nuismer.

Until next time, I hope you're motivated by working in a place that provides a MAP: mastery, autonomy, and purpose.

Remember, if your lips are moving, you're selling.

Life is full of regrets, what matters is, what kind of regrets do you have?

And finally, get a colonoscopy in the morning.

All the best to you. Mahalo and aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Leave a Reply