Rick Smolan is a 1972 graduate of Dickinson College. He co-created the best-selling Day in The Life Series of books starting with Australia and continuing on. This idea, by the way, was rejected by more than thirty traditional publishers.

Before he became a publishing mogul, he was a photographer for Time, Life, and National Geographic. Going back even further, he started taking pictures partially because it enabled him to talk to pretty girls.

He and Jennifer Erwitt co-founded a company called Against All Odds Productions to manage their own publishing projects. Fortune magazine named the company One of the 25 Coolest Companies in America in 1995.

They created the market for large-format illustrated books–you could say they owned the coffee table market. They continued their work with both professional photographers and crowd-sourced projects including Passage to Vietnam, The Human Face of Big Data, 24 Hours in Cyberspace, America 24/7, Blue Planet Run, and Obama Time Capsule.

Their latest book is The Good Fight: America’s Ongoing Struggle for Justice. It documents how much progress America has made against hatred, bigotry, racism, misogyny, homophobia and injustice. This interview was conducted in mid December, 2020–ie, before the day of infamy on January 6, 2021.

In this episode with Rick Smolan, you’ll learn about:

- The role of curiosity in finding your life’s work

- The benefits of stepping up and taking control of your art

- And why he’ll never go back to film

You’re going to love this Remarkable People episode with photo journalist and photographer Rick Smolan.

You might like to listen to Karen Mullarkey’s podcast next.

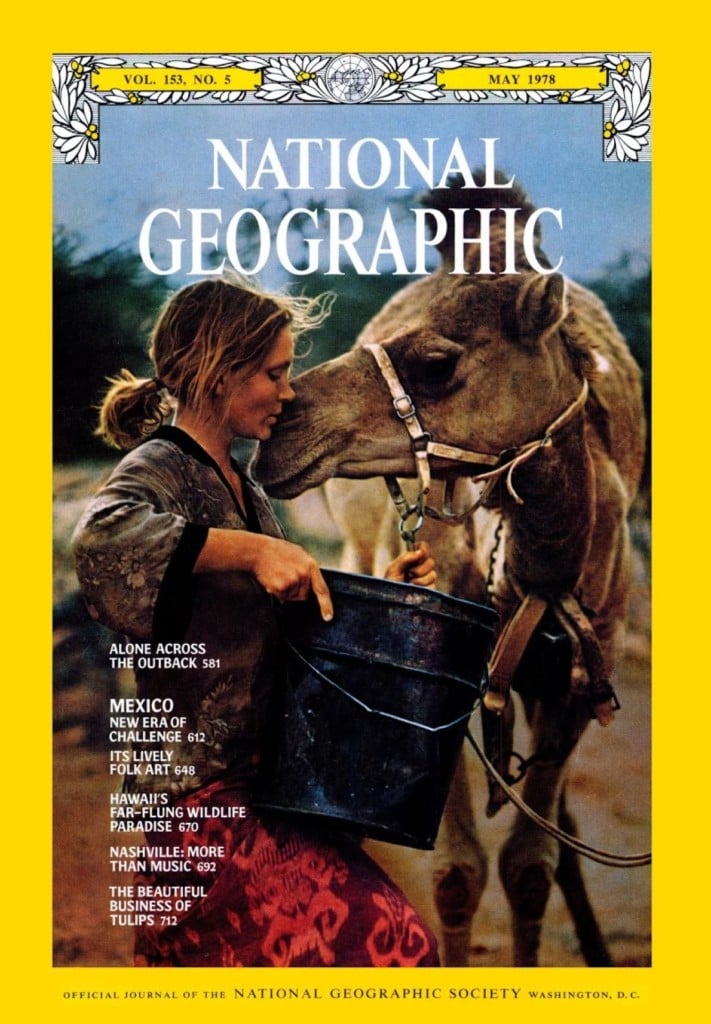

Rick Smolan’s photo of Robyn Davidson was featured on the cover of the May 1978 issue of National Geographic.

Photos courtesy of Rick Smolan.

More about Rick Smolan:

Inside Tracks: Robyn Davidson’s Solo Journey Across the Outback

The Good Fight: America’s Ongoing Struggle for Justice

Rick Smolan’s Trek with TRACKS, from Australian Outback to Silver Screen

Guy Kawasaki: I'm Guy Kawasaki; this is Remarkable People, and now, here's the remarkable Rick Smolan.

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. Today's remarkable guest is Rick Smolan.

He is a 1972 graduate of Dickinson College. He co-created the Day in the Life series of books. These books were about Australia, America, Soviet Union, and many other locations. The idea, by the way, was rejected by more than thirty traditional publishers.

Before he became a publishing mogul himself, he was a photographer for Time, Life, and National Geographic. Going back even further, rumor has it that he started taking pictures partially because it enabled him to talk to pretty girls.

He and Jennifer Erwitt co-founded a company called Against All Odds Productions to manage their publishing projects. In 1995, Fortune Magazine named the company one of the twenty-five coolest companies in America.

Smolan and Erwitt created the market for large format illustrated books. You could say they owned the coffee table market. Their other books include Passage to Vietnam, The Human Face of Big Data, 24 Hours in Cyberspace, America 24 by 7, Blue Planet Run, and the Obama Time Capsule. Their latest book is The Good Fight: America's Ongoing Struggle for Justice. It documents how much progress America has made against hatred, bigotry, racism, misogyny, homophobia, and injustice.

Incidentally, this interview was conducted in December 2020. That is, before the day of infamy on January 6th, 2021.

In this episode, you'll learn about the role of curiosity in finding your life's work, the benefits of stepping up and taking control of your art, and why Smolan will never go back to film.

This episode of Remarkable People is brought to you by reMarkable - the paper tablet company. Yes, you got that right. Remarkable is sponsored by Remarkable. I have version two in my hot little hands, and it's so good. A very impressive upgrade.

Here's how I use it. One: taking notes while I'm interviewing a podcast guest. Two: taking notes while being briefed about a speaking gig. Three: drafting the structure of keynote speeches. Four: storing manuals for all the gizmos that I buy. Five: roughing out drawings for things like surfboards, surfboard sheds. Six: wrapping my head around complex ideas with diagrams and flowcharts.

This is a remarkably well-thought out product. It doesn't try to be all things to all people, but it takes notes better than anything I've used. Check out the recent reviews of the latest version.

Rick Smolan:

I had a D-minus throughout high school. I was just bored to tears.

My parents sent me to a shrink when I was eight years old or something because there was obviously something different about me, which now, I think, was probably a good thing, but at the time, nobody wanted their kids to be different, and they tested me.

I had a very high IQ, but absolutely motivation, which I said, "I could have told you that, you didn't have to pay somebody to do a test." I was just bored. I only wanted to do what I wanted to do.

At twelve. I got my ham radio license, I learned Morse code, I would sit in the basement. I was painfully shy. Morse code was perfect for me, because I could sit by myself in the basement and tap out, you know, have conversations with people, but not have to make eye contact with them.

I'm not a photographer, I'm not a book publisher, I'm not a film producer. I do all those things. This is not a good description, but I feel like a photographic orchestra conductor, which makes absolutely no sense.

What I've been trying to do now for about thirty years is to bring together groups of very talented people, men and women - people from all over the world with a whole different set of skills - and focus them all on one topic that I personally find interesting. So whether it's the global water crisis, or big data, or social justice, or how the human race is learning to heal itself, what the concept of home is. I want to bring photographers, writers, filmmakers, coders, and get them all to use their skills to help take abstract concepts and put a human face on those things.

I don't know what that job's called. I can't wait to go to work every day. I tell my kids, I hope they find something they love to do as much as I love to do. I have so much fun, and I feel so lucky to work with so many talented people. I feel like I'm the least talented person in the room. I just surround myself with people a lot smarter and more talented than me, and then it's like, my relationship with my wife, she does all the work, and I take all the credit.

Guy Kawasaki:

I would make the case that the smartest person is the person who has surrounded himself or herself with the smartest people in the room.

Rick Smolan:

It's kind of a very meta concept, but also, Guy, I'm sure you have the same feeling, which is, “I think I'm smart, and I think I have some talents, but I also feel like I'm the luckiest person in the world.” I feel like I stumbled backwards into success. I don't have a clear view of where I'm going, I just feel like, even when things go wrong, inevitably, when I look back, those mistakes and the things I was freaked out about actually sent me in the direction that I needed to go in but at the time, it felt like the world was ending.

Guy Kawasaki:

How do you come up with an idea like Day in the Life, or The Good Fight, or America 24 by 7? Are you just sitting around in a beanbag chair, drinking wine, and it just pops into your head? Or are you on a twenty-mile bike ride? Or in the middle of sex? When do these ideas happen?

Rick Smolan:

Like a lot of people, I absorb tremendous amounts of information. I'm always reading and surfing and looking at my Twitter feed, and talking to people everywhere, and it's almost like you learn a new word, and all of a sudden, you hear the word everywhere, and there's certain topics that I just find myself thinking, what does that mean?

The word, like, Big Data, sounded like a really abstract concept, but I heard so many people using it, and then defining it differently, and I thought, how would you photograph Big Data? When I started with the idea of that project, people said, "Well, what is it, like, blinking lights on the front of the Facebook data center? How would you photograph Big Data? And yet it became probably the most human book we ever did.

It's almost like watching the planet develop a nervous system, and all of us carrying these devices now, and become, like, the planet's nerves, and there's this feedback loop that we never thought about before. It's like a microscope.

Anyway, to answer your question, it's usually just me being curious about something. I was at TED one day, and Jacqueline Novogratz, who is a wonderful woman who runs Acumen, and she's married to Chris Anderson, who runs TED. We were talking during one of the breaks, and she was saying, "You should do a book about the global water crisis," and I said, "With all due respect, I admire you for putting so much focus on it, but after the third picture of a woman carrying a bucket of water on her shoulders, what is there to say?" And she said, "You have no idea how different the water crisis is from country to country, from culture to culture." She gave me ten examples that completely caught my imagination.

We ended up doing this book, we got Robert Redford to write the introduction to the book, pictures were absolutely fascinating, people were telling us that the amount of water on our planet right now is the same amount of potable water, drinkable water, is the same as when the dinosaurs were roaming the Earth, and yet, there's now, what, seven and a half billion people on this planet, all trying to drink through the same straw. These analogies were just wonderful.

Again, the thing that I find really challenging and rewarding is taking things that sound really abstract, and then putting together a whole variety of media. You know, books that have a smartphone component, so you can point your phone at pictures in the book, and then it plays a YouTube video, or a documentary, or a commercial, or customizing books, where people can actually upload their own photographs, and they're on the cover of the book when it comes out.

The book world is such an old... you know this from your book, Ape, about how to publish your own book. I got turned down by thirty-five publishers when I first came up with the idea of Day in the Life.

You asked me, how did I come up with the idea of Day in the Life? Basically, as a photographer, I got hired by Time Magazine when I was twenty-four. I had never studied photography. I did the yearbook, because having a camera was a great way to talk to girls. I was very shy when I was a kid.

My dad gave me a camera, and suddenly, for the first time in my life, I could walk up to strangers, particularly beautiful girls, and start a conversation with them. As a really shy kid, I always thought that when people were born, other people, that most people were born with something, part of their toolkit was how to relate to other people, and I always felt it had just been left out of my toolkit. I thought, if I watch other people enough, if I just hung around and watched people, I could imitate what they were doing, and learn from them.

Now that I think back, being a photographer is the perfect way to observe other people. I was really lonely as a teenager. I remember, I would go out and sit in the playground at my school at night by myself, and stare up at the stars, and I had this, I knew this was a silly idea, but my way of rationalizing my inability to talk to other people was that I was an alien sent here to observe life on Earth, but not to interact. I just remember thinking, sitting on the swing at night, looking at the stars, saying, "Could you please just come and get me and take me out of here?" Because I was really lonely and miserable as a kid, and then it's so funny that the thing that actually, I think, was my handicap, became my strength. It's observing other people.

It started out as being a photographer, but so often, working for publications, somebody in New York or Paris or London would send me off on assignments around the world, and then I would take all these pictures, and I'd pick up the magazine, and they would only use the pictures that I shot that backed up their preconceived idea of what the story was.

Very often, I would get out there, and they were still back in New York City or Paris or London, but I was actually out there seeing what was going on, and they had already decided what the story was. They wanted me to illustrate their preconceived ideas, and as a twenty-four-year old kid, I'm not going to tell the editors at Time or Newsweek or National Geographic that they're wrong, but after five or six years of being in the field, living in hotels, and then running into other photographers, I realized all my heroes, and my peers, and the new crop of young photographers, we were all so frustrated that so often, the pictures that actually told the story the best were not the ones that the magazines used.

So one day, sitting in a bar on Bangkok with a group of other photographers, I said, "Wouldn't it be cool if a hundred of us all could all go," I was living in Australia at the time, I said, "what if we could have a hundred photographers descend on Australia, and do the Olympics of photography?" We'd have people from thirty countries, we'd spread everybody out, we would spend months getting ready to make sure we were geographically and thematically spreading them around the country, but we'd say, "On your mark, get set, go. You have twenty-four hours,” and hopefully, they would find things that were even more interesting than what we'd asked them to photograph. It's probably the only time that most photographers were allowed to scrap the assignment, and go off and find their own stories and their own pictures.

I went to thirty-five publishers, pitching this - what I thought was a brilliant idea - and they laughed be out of their offices, and said, "You're talking about a project that's going to cost millions of dollars to have a bunch of your friends fly to Australia, have a big party, who would care? Why don't you buy stock photos from Getty Images? Who would know you didn't show them on one day? And how many kangaroos are going to be in the book?" It's like, oh my God, this is exactly the thing that I objected to so much with people, let's just do another book that looks like every other book. So I could not find any publisher to back the project.

I went to private companies, I actually went to Steve Jobs, I went to the head of Qantas Airlines, I went to the head of Kodak, and I begged for film and computers and hotel rooms and cars. I got almost no money at all, but Steve gave us computers for many of the projects. In fact, we actually used Macintoshes, when Macs were first released. We actually paid all the photographers and all the editors with Macintoshes.

Our projects actually got the first Macs into Time, Newsweek, National Geographic, The London Sunday Times, the Asahi Shimbun, Perry Maps, they all came in through the backdoor, through our projects, because that's how we paid everybody. I don't know if you knew that, but we gave away almost 1,000 Macs between 1984 and 1990.

We actually did the first best-selling coffee table book was designed on a Mac, Day in the Life of the Soviet Union was the first book that was, I think, coffee table book ever done on a Mac. It was really fun, and so many photographers said, "What would I do with a computer? Why would I need a computer?" And then, of course, the moment they had it, everybody fell in love with it.

To make our projects stand out, and because I'm a tech junkie, I always try to incorporate some cool tech component into the project or into the book. So when we did A Day in the Life of the Soviet Union, Akio Morita, the head of Sony, gave us 100 handycams. Every one of our photographers turned their KGB assistants into film crews, and then Barbara Walters and 20/20 did two evenings, all with footage shot by our KGB agents, which was pretty fascinating.

As I said, we gave Macs to people, we started doing books where you could, as I said, you know, we did a project called America 24/7, right after 9/11, where we... it was the first time that digital cameras had outsold film cameras. So we invited, not only did we send 1,000 photographers around the United States, we actually went crazy and had twenty photographers in every state, but also opened it up to the public, and said, "You can participate in telling America's story to the world."

We got millions of pictures from the public, and then a young kid on our staff, Josh Haner, who had been interning for us since he was sixteen years old, I met him - I spoke at his high school, Lick-Wilmerding in San Francisco - he started interning for us, and when he was twenty-two, he had just graduated from Stanford, still would work for us on projects over the summer. My daughter had just been born, and he said, "Do you have a picture of Phoebe?" And I said, "Yeah, why?" He said, "Just give me the picture."

The next day, he came in, and he showed me a replacement wraparound dust jacket that had Phoebe on the cover, but it had the logo, it had the reviews from the New York Times, and he said, "I wrote the software, I found the vendors, and for $5.95, anyone buying our book can get the book with their own family on the cover, with their wedding from... their parents' wedding from 1940, their dog's picture, whatever."

Oprah Winfrey heard about it, and put us on her Favorite Things show. This kid who'd been interning for us since he was sixteen, basically was responsible for the success of that book. Then, Josh, during that project, met the editor of Fortune Magazine, a woman named Michele McNally, wonderful director of photography, who then went on to the New York Times, and Josh, who wanted to be a photographer, not only was he a great coder and a great businessman, but he was a great photographer, he went to work for Michelle.

When he was twenty-seven, he called me one day, and said, "Are you sitting down?" And I said, "I'm actually driving across the Golden Gate Bridge. Why?" He said, "I just won the Pulitzer Prize in photography."

So here is this kid who'd been sixteen who came up to me with a Kodak box of prints, shaking, because he was so nervous to show me his work, and I felt like the proud father. Guy, what I love about these projects is the serendipity of, give out 150, 1,500 rolls of film to the most talented photographers in the world, and two days later, you have these extraordinary images. Every picture in our book would have been different if it had been shot the day before or the day after.

That's what I loved about the Day in the Life projects, is that there was that sense of discovery, not just re-illustrating all the old clichés, but actually seeing things for the first time through fresh eyes; also having people from all these different cultures looking at a country. Again, I like having a plan, but I also am very open to that plan changing, and that's, I think, the most exciting part of being a journalist, is being open to actually seeing what's really going on, and not just illustrating your preconceived ideas.

Guy Kawasaki:

That answer you just gave is probably the single longest answer to one question in the history of my podcast. I mean that as a positive.

Rick Smolan:

I'm sorry, I need somebody to do that symbol of the cutting your throat symbol, meaning stop talking.

Guy Kawasaki:

No, the whole thing was interesting. I'm almost a little bit afraid to ask this question, but one of the people that I interviewed before for this podcast was Karen Mullarkey. Her episode is one of my favorites of them all. Did you ever work with her? Was she one of those photo editors who picked the wrong photo from your selection?

Rick Smolan:

No. No, in fact, Karen was our director of photography on many of the projects. I love Karen. She's a dear friend, and incredibly talented, brilliant, just totally unique. Karen doesn't remind me of anybody else, Karen reminds me of Karen. She's such a force of nature.

Karen actually was one of the few editors that I worked for over the years who was open to discovery, and who would encourage photographers to go way beyond what was expected of them. In fact, one of my most favorite memories is, there's a photographer named Arthur Grace, who is very close to Karen, and she sent Arthur to photograph Robin Williams, when he was sort of at the top of his career. Robin had just gotten divorced from his first wife, and Arty had just gotten divorced from his first wife. So Arty and Robin became literally best friends.

When Robin turned forty, he had a huge birthday party at his ranch up in Sonoma, or Napa, I forget where it was, and because Arty was friends with Robin, he didn't want to be the photographer at the party, he wanted to be one of Robin's friends. So Karen called me and said, "Would you be open to being the photographer at Robin Williams' birthday party?" And I said, "Don't throw me in the briar patch, are you kidding?" His wife, Marcia, said, "What will you charge?" And I said, "Are you kidding me? I would pay you to be a fly on the wall at that party."

So one of my favorite memories, thanks to Karen, was my gift to Robin for his fortieth birthday was to be a fly on the wall from early in the morning, before any of the guests came, to late at night when everybody had left. It was just one of my favorite days. It wasn't just movie stars, it was his high school music teacher. It was Wavy Gravy. His mother was there, his nanny.

I don't know if you ever met Robin, but he was just the kindest, gentlest, funniest, most open soul I think I've ever met. I have many reasons to feel grateful to Karen, but that was certainly, probably the top of my list.

Guy Kawasaki:

I want to shift gears, and I want you to explain the project The Good Fight.

Rick Smolan:

I was at TED several years ago, and they have these dinners at night, where they sit you with random people. The guy sitting next to me was Jonathan Greenblatt, who had just become... just about to become the head of the Anti-Defamation League. He said, "Have you ever done a book about social justice?" I said, "What do you mean?" He goes, "I've seen your books, I love your books, and the TED books," many of my books have been out to everybody at TED, which is an incredible honor, they have these gift bags that they give out of cool stuff to all the people that attend TED, and I said, "All my books are really original photography, I don't use stock photos. We send photographers out." He said, "No, I know you do that, but what would you think of actually doing a project where you look back, over the last hundred years of history, to remind people how much progress has been made in America towards equality, towards social justice, towards inclusion?"

He said something to me that really struck a chord, he said, "If you say to someone who's Jewish, or gay, or female, or Native American, or African American, or any minority in America, would you rather be Muslim or Jewish or Black or female or gay or Latino-American in 1920 or 2020?" He said, "What do you think the answer will be?" I said, "Well, definitely today." He said, "Exactly," but he said, "How about if we fund a project where you and your team spend half a year going through all the great photographs ever taken over the last hundred years through archives at the Library of Congress, people's basements, call photographer's families, and ask if you could look at the original contact sheets."

Again, we'd never done anything like that before, and it was so interesting, and you would think it would be depressing, looking back at the history of civil rights, and lynchings, and of course a lot of this was really disturbing, but it was also discovering these individuals, people that stood up against injustice, that risked their lives, risked their careers, their reputations, to move America in the right direction. Then we decided to add this smartphone component, so you could point at a photograph, and there's Martin Luther King giving his “I Have a Dream” speech, or George Takei talking about growing up in a detainment center in America, or his parents growing up in the Japanese internment camps during World War II.

Again, hearing the voices of people who were intimately involved - John Lewis, Tim Cook - just making the decision to come out and tell the world that he was gay, because it would help other people who were not in positions of power. We had heroes in each of the chapters in the book, and we sort of show how bad things were through incredibly powerful photographs, and then we also showed that sort of arc of history, of how much better things are today.

We also wanted to remind people how fragile this progress is, that we may pat ourselves on the back, and say, "We have a long way to go, but look how much progress we've made." As we've all seen in the last four years, it turns out a lot of that progress is a lot more fragile than any of us thought was possible. We didn't think that we could turn the clock back the way that the Trump administration, and the people he surrounded himself, have been spending so much energy to take us back to the Dark Ages.

So the book has turned out to be, oddly enough, it's unlike any book we've ever done before. It's not original photography. There was some original photography in it, but most of it was researched. But the analogy I always give to people with our projects, it's, imagine you're doing a jigsaw puzzle, but you lost the box that all the pieces came in, so you don't know what it's supposed to look like. You keep trying to... does this fit together, does that... we have too much of that, how does this, how do these different stories relate to each other?

I think of all the books I've ever done, The Good Fight is the one that I'm, by far, the most proud of, and the one that I think is, unfortunately, the most timely, given where America is right now.

Guy Kawasaki:

Each member of Congress got a copy of The Good Fight, right? Do you have any great stories, like, Ted Cruz returning it, or Marco Rubio burning it, or Lindsay Graham banning it from South Carolina libraries?

Rick Smolan:

No, but in fact, what's so funny that you're asking this question is, last night, my phone started blowing up, I started getting all these texts within two or three minutes, from probably thirty different people, and I thought, "Oh, my God, what's going on?" The first thing you think when your phone is dinging every second is someone's died or something terrible has happened.

I opened up my messages, and Stacey Abrams and her campaign manager were on Lawrence O'Donnell's show - is that his name? Lawrence O'Donnell? Apparently, I gave each of them a copy of The Good Fight book at Kara Swisher's code conference last year, just because I admire them both tremendously.

Stacey's extraordinary, and her campaign manager, I'm sorry, I forget her name, is also just equally mind-bogglingly smart and passionate, dedicated, and I guess in the interview, The Good Fight was strategically placed right behind both of them. So everybody was taking pictures of the screen and sending it to me, and it was just so funny, because, I mean, I didn't know if it was good news or bad news, it turned out to be really good news, but I don't have any great stories to share.

The book was chosen by People Magazine as one of the Ten Books of the Year. It won the Thomas Franklin... I forget what the name of the award is, but it won many awards, and we're actually, right now, in the middle of negotiating with several broadcasters about doing an eight-part series that I would direct, basically taking each of the chapters in The Good Fight, and using historical footage the way we used historical still pictures to tell the story.

I think, if anything, the message of the story, and the sense of hope and progress that are encapsulated into The Good Fight. I think people are even more hungry for it right now than when the book first came out.

Guy Kawasaki:

You said you're not a photographer earlier, but I beg to differ. You were a National Geographic photographer. What, today, is your go-to camera?

Rick Smolan:

Like most of my friends, I used to be a Nikon photographer for most of my career, and then, when digital came about, Canon cameras, their sensors were better at the beginning of the sort of digital camera revolution. So I switched to Canon.

About three years ago, every single one of my friends in the photo business, and as I said, I did work for the Geographic, and I worked for many magazines, and I had ten covers with Time Magazine. I was very fortunate to do all this pretty much in my twenties. Now, I photograph my kids, and Robin Williams' birthday party, and things like that, but we all switched to Sony.

Sony was half the weight, the sensors were better, the technology was better, and pretty much the entire industry... and Sony came from out of left field. Nobody ever thought of Sony as a high-end, professional camera at the beginning but they've really eaten the lunch of all their competitors. I love the camera, and of course, now you can shoot video with it, 4K video, as well as stills.

I use the A7 series. A9 is really good, but it's more... I think of it more for, like, sports photographers, where you need to shoot forty frames at a very high resolution. I'm still from the world where you had to change film every thirty-six frames. So I tend to not use it like a machine gun.

I'll tell you a funny story, which is that when digital cameras first came out, my wife, Jennifer, who's my partner, both in my books and also in my life, she said, "Could you buy one of those digital cameras, and read the manual, and then teach me how to use it, so I can photograph the kids?" And I said, "Oh, yeah, sure, okay." I had no intention whatsoever of ever giving up film. I used my Leicas, and I used, at that time, I was using my Nikon still. And I literally never touched my film cameras ever again after one day of using a digital camera.

Now, I wasn't shooting professionally at that point, I was still photographing my friends and family, and taking my own personal pictures, but it was so seductive to be able to share the pictures, throw away the bad ones, pull the images into photos on my Mac and brighten them, and open up the shadows, and lower the contrast, and then share them, literally, within seconds. Instead of taking it down to the lab, developing the film, waiting a day or two, making prints, mailing the prints to people... there were so many steps involved in sharing your pictures.

With the digital, in iMovie, I made little movies of my kids, added music to it, and it was literally cold turkey. From one day to the next, I never picked up my film cameras ever again. Now I have seven stops, I could overexpose or underexpose by seven stops, and still come up with a great picture whereas with the slide film, if you're even slightly off, you didn't have a picture. So it's so forgiving.

Guy Kawasaki:

I take it you shoot raw?

Rick Smolan:

I do. Yes. My friend, Russell Brown, first told me, when raw was first explained to photographers, what it was, because at the time, storage was still very expensive, so people were reluctant to fill up those little memory cards by shooting raw, but if you didn't shoot raw, you basically were kind of stuck with what you got, whereas when you're shooting raw, it gives you this astounding latitude. Do you use Photoshop at all?

Guy Kawasaki:

No, I use Lightroom.

Rick Smolan:

Okay. When Adobe bought Photoshop from the Knoll brothers, they thought they were buying something called the Barney Scan. It was this device you could put your slides into, and it would scan them. The software that came with it was Photoshop, and the software was free, everybody thought that what they were buying was a physical device.

Adobe bought it for probably next to nothing, and I always thought of Photoshop as like the Post-It Note. When 3M, one of the engineers at 3M put some very weak glue onto these pieces of paper, and it didn't very stick very well to anything, but they could use it, the engineer who created and started sticking them on his monitor to remind himself to bring milk home to his wife, and people said, "What is that?" And people said, "Oh, could I have some of those too?"

The Post-It Note became this entire industry because of an accident. I know that Adobe did not realize when they bought Photoshop that it was going to become one of the tent poles of the company. Also, all the special effects in Hollywood now are also basically using the Knoll brothers' underlying algorithms.

It's extraordinary, when you look at Adobe, and you think that John Warnock came up with Postscript with such an abstract concept, just as Steve was inventing the Mac, which was just when Postscript laser printers were coming out, those three things had to happen at the same time, in order to come up with the publishing revolution.

Then, they did it again with Photoshop, and then they've now done it again with PDFs. There are three things that are really abstract that all led to Adobe's incredible success.

Everybody talks about Google, and Facebook, and Apple, and Amazon, and to me, Adobe's like the little engine that could. Everybody's talking about all the controversy, but Adobe just keeps innovating, even converting people from buying new copies of the software every year to subscribing, Adobe was way ahead of most of their competitors in the digital world of converting people to an ongoing subscription, which was one of the reasons that their stock has done so well. I always tell people, "You're all looking at the flashy, showy..."

Guy Kawasaki:

But I work for Canva.

Rick Smolan:

Yes, all right. Erase that answer.

Guy Kawasaki:

One more camera geek question. You get to have only one lens. What lens is it?

Rick Smolan:

It's really hard to have one lens, because I either want wide angle, like a twenty-four mm, or I want, like, a 105, which sort of gives you enough of a zoom to separate people from the background, you can throw the background out of focus. So when I was a photojournalist, and I had many different lenses, I had a 300mm, I had a zoom, a 7200, but just my regular walkaround kit would be twenty-four, which would let me take some kind of surreal pictures. Not distorted like fisheye, but just wide enough to make people look twice.

Then, the 105 was just a great portrait lens. So I guess that would be my camera nerd answers to those things.

Guy Kawasaki:

Who are your photography heroes?

Rick Smolan:

The first one is my father-in-law, who I first saw his work when I was sixteen years old, Elliott Erwitt. He's the photographer... his work is in every museum in the world. He has one foot in the world of journalism and one foot in the world of art, like, the artists think he's a journalist, and the journalists think he's an artist, which is a good back and forth. He did that very famous picture, amongst many others, but the one of Nixon poking Khrushchev in the chest, of John-John saluting at JFK's funeral. There's a very famous picture in France of a gentleman with a beret on a bicycle with a little boy behind him and a loaf of French bread on the back of the bicycle, and that was a campaign he shot for the French tourism authority.

He has many, many, many hysterical photographs of dogs. His pictures are like New Yorker cartoons. You have to look at them twice, and then you realize the juxtapositions of people in the picture, and he does it over and over and over again.

Elliott's ninety-four now, he's still doing two books a year. I met him when I was in my early twenties, and he's a man of few words, he's very funny, but he doesn't talk that much, but when he does, you fall over laughing, he's just so funny. He's part of the Magnum Collective, he's part of one of the great Magnum photographers.

My other hero growing up was Cartier-Bresson, who's also black and white, the photographers that have the black border around their pictures, which is a sign of honor, or a badge of honor, because it shows you they composed in the viewfinder. So one of the things a lot of photographers, at least back in the day, would do to... cropping a photograph was considered to mean you didn't get close enough, or you didn't compose it properly.

The idea is the photographs that we would do to impress each other was when you completely framed the picture inside the viewfinder, with no cropping afterwards. In order to show that that was how you shot it, there's a black border around the outside of... this is black and white, I'm talking about.

Steve McCurry, that took the picture of the Afghan girl that's the cover of National Geographic, it's probably the most famous picture in the world now. Sebastian Salgado. Many of these photographers are actually Magnum, either were or are Magnum photographers.

Magnum is, I think, the photographers that a lot of us growing up admired the most, and wanted to emulate. They would live in hotels eleven months of the year, they would go to the places that other people were afraid to go to. Eugene Smith photographed Minimata.

Again, I'm really dating myself here, because these were people back probably in the '70s and '80s that were the heroes of photojournalism. David Douglas Duncan, John Loengard, who was the director of photography at Life, but a wonderful photographer in and of his own. David Burnett, who's a contemporary of mine, who got me started in the professional world of photography.

Guy, the thing I loved and love about the world of photographers is that even though we are competing with each other, the moment you put your camera down... I mean, when you're photographing, it's every man and woman for themselves, but the moment you're not taking pictures, it's your family, and the same men and women would show up at every plane crash, at every Pope visit, there'd be a disaster, at every typhoon.

There were about a hundred men and women that we all knew each other, we would see each other, and when there were events that lots of photographers showed up at, we'd see each other, but then a lot of us were doing our own private, personal projects. I was always just so surprised that people were so generous, saying, "Here's the home number of the American ambassador, the next time you're in Vietnam." Or, "Don't buy this batch of film, because it's known to have a color cast that will ruin your pictures." Or, "Don't go to that border, because they extradite your film, go to this other border."

People were just so generous, and most photographers, I have to say, are not very good in terms of their relationships, in terms of romantic relationships, because they're always on the road. So a lot of them had terrible marriages, and their first love were their cameras and their pictures... not their cameras, but I think it's really hard for journalists, sometimes, to balance those two parts of their lives.

I was fortunate to have been very successful at a very young age, so I was able to actually look at my friends. When I was in my twenties, I was looking at my friends who were in their fifties, and thinking, "I don't want to be schlepping around the world, and have broken marriages, and kids that I never see, when I'm fifty years old." I was fortunate to have those wonderful experiences in my twenties, but be able to use my heroes as the negative examples of things I didn't want to end up doing when I was their age.

Guy Kawasaki:

Somebody young is listening to this, and is saying to himself or herself, "I want to be a professional photographer, I want to be a photojournalist." Or, much more mundane, "I want to be a great photographer." What's your advice?

Rick Smolan:

Well, two things. I think it's really hard right now to make a living as a photographer. I have friends, many friends, who are incredibly talented, who, ten years ago, were making three or four hundred thousand dollars a year as photographers, who are lucky to make, you know, $50,000 a year. Not because they're not still great photographers, but because photography has become so commoditized. You can buy one dollar photographs now from iStock photo. The fact that everybody's got a camera in their pocket has actually made photography, in some ways, less valued.

I’d tell young photographers a couple things. One is, you can't just be a still photographer. You need to be a storyteller. You need to tell your story in video, you need to tell your story in audio, you need to record the audio, you need to shoot video, and you need to do still, and you need to, if you can, either work with a great writer, or write things yourself. You need to be a man or woman of all trades.

The second thing I tell them is, don't wait for somebody else to wind you up and tell you what to care about. Don't wait for assignments. Find things that you want to expose or share or bring to life, and use your own money, your own time. Go out and photograph those things, and start showing editors at magazines how hard you work for yourself because if you're going to work day and night, and spend the time and the money to photograph something that you're passionate about, that editor's going to say, "Wow, if that guy or that girl works that hard on their own projects, imagine how hard they're going to work when I'm actually giving them money and resources, and flying them around the world, and getting them into things that I want them to photograph.”

There were two stories that I did as a photographer that were turning points for me. One was Robin Davidson. She walked for 1,700 miles alone for nine months through the outback of Australia. She crossed through the Gibson Desert by herself and I had to fly out and find her and photograph her five times, which was absolutely fascinating.

She said most photographers that she had met up to that point basically waited for someone else to tell them what to photograph. Her comment wasn't meant as an insult, it was more like saying, "You should use the power of your photography to change the world, and not just document it."

The guys who made The King's Speech turned her story into a feature film, which came out about four years ago. It's called Tracks and it was very surreal to see how Hollywood took a story of a journalist photographing a woman who doesn't want to be photographed, and how they turned it into just a beautiful film.

So if any of your listeners are indie film aficionados, it's been one of the top ten films on Amazon for the last year. A young actress named Mia Wasikowska plays Robin, and Adam Driver, who is Kylo Ren in Star Wars, plays me in the movie, which, as you can imagine, was very surreal.

They actually flew Robin and me back to be on the set in the outback, watching these actors literally wearing our clothes. They looked at my photographs and actually built the sets and put the clothes on the actors based on the photographs that I shot, and it was really one of those died and gone to heaven moments. You couldn't quite believe this was happening.

The second story is a TED talk, I gave a TED talk about it, which is, at the end of Robin's trip, she challenged me, as I said before, to use my skills as a photographer to not just document things, but to change them. I found out that there were 40,000 children all over Southeast Asia who had been fathered by American GI’s who were based in these countries, and then abandoned these children. That was a story that nobody in America wanted to tell, I couldn't get a single magazine here, or publication, to touch the story.

In the middle of doing the story, I was left an eleven-year-old in a Korean woman's will. So my TED talk was about what happened when I was twenty-eight years old, and suddenly had this eleven year old girl, who looked almost completely Western, but didn't speak a word of English; the saga of how she changed my life.

It sounds like, "Oh, this American photographer went and changed this little girl's life," but in fact, she changed my life and the lives of many other people. So if any of your listeners are interested, it's called Natasha's Story. In fact, you can go to natashastory.com, and it plays the TED talk.

Most of the children that I had photographed were psychologically disturbed because, imagine, from your earliest memories, being taunted, made fun of, beaten up, and being called names, and being ridiculed, because of how you look. Even though most people that saw Natasha thought she was incredibly beautiful, in Korea, they thought she was the ugly duckling. She didn't look like anybody else, and Natasha, unlike all the other children, was not like that, she was not psychologically disturbed. She had been raised by a very, very strong woman, her grandmother, who was like the village wise woman in the village she'd grown up in.

Natasha, she's a leader. At one point, after the grandmother died, I temporarily got her into an orphanage in Korea, where there were seventy-five children, and a Maryknoll priest named Father Keene, who with three other women were trying to look after seventy-five children. I got her into the orphanage while I tried to find a family to adopt her. About two weeks after she got to the orphanage, I would go off and do other assignments for Time Magazine, and then come back to see her.

Father Keene called me into his office, and said, "I have to talk to you about Natasha." And I said, "Oh my God, what happened?" He goes, "No, just close the door." So I closed the door, and said, "You know, I've had several hundred kids come through this orphanage, and as you know, a lot of them are pretty psychologically damaged,” and he said, "I've seen three kinds of children. I group them this way. I've seen plastic kids, where no matter what happens to them, it kind of bounces off, and they are who they are no matter what happens. I've seen mostly glass kids, that they're just shattered. The experiences that they've had from a very young age, their personalities are really in pieces,” and he said, "I have only seen two children in all the years I've been doing this that I think of as steel children, and the more adversity they go through, the stronger they get."

He said, "Natasha, the second day she was here, came into my office, and politely told me that this place is a mess, that I need to clean it up, and that she basically assigned each of the older girls to one of the younger children, and said, 'From now on, you're responsible,' she said this to the other girls, she said, 'Each of us is going to be responsible for one child here. We're going to bathe them, we're going to feed them, we're going to keep them clean, we're going to clean their room.'" He said, "She's eleven years old, and she's now running the orphanage, in two weeks." He said, "I've never seen anything like this."

Natasha, she now lives in Pleasanton, I think she's fifty-four now. My best friends ended up adopting her, but Natasha, basically, no matter where she is, she takes over. Not in a bossy way. Her grandmother raised her to be in charge, and so she's given me advice about my marriage, about my children. She is a force of nature, and she was the same thing with her family, with her husband, with her kids. Again, she's not bossy, she's just very confident, knows what she wants, and is used to creating order out of chaos.

Again, Natasha, and spending time with her, just made me realize that I needed to go up a level, and actually command of the situation, and not always be at the mercy of editors and other people. That's when I started doing books, because I figured, I'm always going to be a cog, no matter how good I am as a photographer, I will always be a cog in somebody else's machine. It's some editor, or somebody in the advertising department, is going to make decisions that are completely out of my control.

That probably sounds egotistical, but I think she inspired me to not just always be passive and feel lucky. I was very lucky as a young photographer, but I decided I needed to be running the show myself.

Guy Kawasaki:

So there you have it. A story how the desire for creative control, and a high level of intellectual curiosity, has shaped a remarkable career.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, and this is Remarkable People. My thanks to Peg Fitzpatrick and Jeff Sieh for helping me make Remarkable People remarkable.

Vaccines are on the way, but we still have to wash our hands, avoid crowded places, and wear a mask. When I am offered the chance to get vaccinated, I am going to jump on it. Mahalo and aloha.

This episode of Remarkable People is brought to you by reMarkable - the paper tablet company.

This is Remarkable People.

Sign up to receive email updates

Leave a Reply