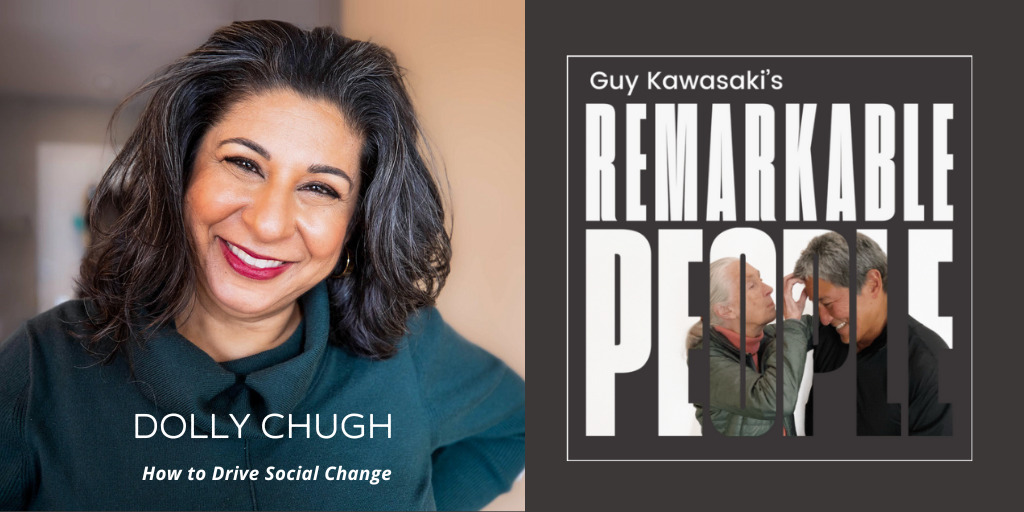

Welcome to the Remarkable People podcast. We’re on a mission to make you remarkable. Helping me in this episode is the remarkable Dolly Chugh.

Dolly is a professor at the New York University Stern School of Business. She teaches MBA courses in leadership and management.

She is also a faculty member in the KIPP Charter School network’s School Leadership Program, where she has taught about 1,000 current and future principals of schools in underserved communities.

She received her BA from Cornell University, earning a double major in Psychology and Economics, an MBA from Harvard Business School, and a Ph.D. in Organizational Behavior and Social Psychology from Harvard University.

Angela Duckworth describes Dolly as “the wisest and warmest of behavioral scientists.”

Dolly’s TED Talk, How to let go of being a “good” person — and become a better person, was named one of the 25 Most Popular TED Talks of 2018 and currently has almost 5 million views.

She is the author of The Person You Mean to Be: How Good People Fight Bias, and has a new book, A More Just Future: Psychological Tools for Reckoning with our Past and Driving Social Change.

It is a must-read. Now more than ever, our society needs to develop grit and resilience to reckon with our past and whitewashed history. Thanks to Katy Milkman, who introduced me to Dolly.

If you enjoyed this episode of the Remarkable People podcast, please leave a rating, write a review, and subscribe. Thank you!

Transcript of Guy Kawasaki’s Remarkable People podcast with Dolly Chugh:

Guy Kawasaki:

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

I'm Guy Kawasaki and this is Remarkable People.

We're on a mission to make you remarkable.

Helping me in this episode is the remarkable Dolly Chugh. I sure hope I pronounced her last name right. You'll see why.

Dolly is the professor at the New York University Stern School of Business.

She teaches MBA courses in Leadership and Management.

She's also a faculty member in the KIPP Charter School Networked School Leadership Program.

She has taught approximately 1,000 current and future principles of schools in underserved communities.

She received her BA from Cornell University where she earned a double major in Psychology and Economics.

Her MBA is from Harvard Business School and she has a PhD in Organizational Behavior and Social Psychology also from Harvard.

Angela Duckworth describes Dolly as "the wisest and warmest of behavioral scientists".

Dolly's TedTalk, How to let go of being a good person and become a better person, was named one of the twenty-five most popular TedTalks of 2018. It currently has almost five million views.

She's author of, The Person You Mean to Be: How Good People Fight Bias.

She has a new book out, A More Just Future: Psychological Tools For Reckoning With Our Past And Driving Social Change.

It is a must-read. Now more than ever, our society needs to develop grit and resilience to reckon with our past and whitewashed history.

Thanks to Katy Milkman, who introduced me to Dolly and made this episode possible.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People. And now here's the remarkable Dolly Chugh.

First I have to say this word, Varadarajan.

Dolly Chugh:

Oh, yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

Is that right?

Dolly Chugh:

That's a deep cut there. Gita Varadarajan. I haven't said her name in a while. I hope I'm saying it right. Varadarajan.

Guy Kawasaki:

So I was close, right?

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah, good work.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay.

Dolly Chugh:

You went all the way back.

Guy Kawasaki:

And your last name is Chugh?

Dolly Chugh:

Chugh.

Guy Kawasaki:

Chugh.

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah, Chugh. It's like the sound in good.

Guy Kawasaki:

Because I want to be sensitive.

Dolly Chugh:

Thank you for trying. How do you say your last name?

Guy Kawasaki:

My last name is, you can call me anything you want. It's Kawasaki.

Dolly Chugh:

Kawasaki. I've heard you say it on your podcast.

Guy Kawasaki:

In your preface of the Person You Mean To Be, you cite of all books, Hillbilly Elegy.

Fast forward to today, what does J. D. Vance's alignment with Donald Trump mean?

Dolly Chugh:

I have wondered about that, because that book we saw so much heart and so much humanity and so much thoughtfulness and intelligence.

I don't follow his career closely, but I am aware that he's aligned himself and I find that surprising and disappointing and confusing.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's it? You don't have an explanation?

Dolly Chugh:

The explanation would seem to be that, it's hard to believe that he believes what he's saying, because of what he wrote.

That's the part that's confusing. If we didn't have evidence that he thought differently from his book, then it wouldn't be so confusing or surprising.

I don't have an explanation. He clearly is running for office. Maybe it's strategic.

Guy Kawasaki:

I guess. But the question you have to ask is, does the book reflect his true beliefs or is his true belief now coming out and the book was BS?

Dolly Chugh:

Fair enough. That's a fair question.

I guess I had assumed the book would be more true, but we also don't know. Books get ghost written. I always assumed he wrote it, but yeah. I don't know. He's a mystery and I've wondered. I have wondered more than once.

Guy Kawasaki:

So this is not the J. D. Vance podcast, that's enough about him.

Dolly Chugh:

Enough about him.

Guy Kawasaki:

For me, give me the bias for dummies overview. Give me the gist of bias.

Dolly Chugh:

The gist of bias is that most of our mind's work happens on autopilot.

One study says that in the snap of my fingers, we each had eleven million thoughts, only forty of which were in our conscious mind, and 99.9999 percent of which were outside of our awareness.

Like, you understanding the words I'm saying without having to think deeply about what they mean, or feeling the temperature of the room air around you without thinking about that, or knowing to sit up and not lie down right now without consciously think about it.

Those are things we're doing on autopilot and those are what we mean by eleven million thoughts like little T thoughts.

And because so much of our mind's work is outside of our awareness, on autopilot, there's thoughts and actions that we aren't always aware we're engaging in.

And as a result we may sometimes engage in unconscious biases that would surprise us, that part of our brain, the forty big T thoughts might fight it out if it knew what the rest of the brain was doing.

Guy Kawasaki:

Cool.

Dolly Chugh:

I just want to say that, I just spoke about only one form of bias, the one I'm most familiar with, unconscious bias. There are of course other forms of bias, conscious bias, the kind that the big T thoughts part of our brain, very explicitly says,

I don't like this kind of thing, I don't like Pepsi or I don't like this kind of person. And those are also biases. It's just not the kind of bias I study.

Guy Kawasaki:

So you mentioned that you've been in meetings where, because you're a woman and you're Indian, some white male assumed you were the secretary assistant or asked you to turn the lights on or off or go get coffee or something.

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

Would you say that's unconscious bias? Or conscious bias at this point?

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah, that's an interesting question. And of course I don't know why he assumed that. We just string together evidence in these instances. I would think it was unconscious bias. I've made the same mistake.

I attended my Business School reunion before I became an academic, I had a business career and I have an MBA, and I went to my MBA reunion where they have people of different eras. It's every five years classes, so you can be there with someone thirty years older than you.

And there was an older black woman who was standing near the registration area, where I was also to register, and she was considerably older than me and I assumed she worked there. I assumed she was there to take care of an administrative task of getting me checked in and then was embarrassed to realize she was there, just like I was, as an MBA alum.

That is not to diminish the roles of setting up rooms or checking people in. It's simply to say that the assumption that just based off of visually looking at somebody, I know they're in that role.

That's the unconscious part, that I've just created this mental association between a particular demographic and a particular role.

Guy Kawasaki:

Can I tell you a great unconscious bias story?

Dolly Chugh:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

Firsthand knowledge.

Dolly Chugh:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

So my wife and I used to live in San Francisco on Union Street where Union Street dead ends into the Presidio.

Dolly Chugh:

Okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's a very nice part of San Francisco.

And one day I was out there trimming the bougainvillea hedge and this older white woman comes up to me and says, do you do lawns also?

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah. What are your rates?

Guy Kawasaki:

I immediately confronted her and I say, I'm Japanese, so you assume I'm the yard man.

And she says, no, you're just doing such a great job, I wanted to know if you do lawns.

So, that's a good story about unconscious bias right there.

Dolly Chugh:

That's a great story.

Guy Kawasaki:

But wait, it gets better.

Dolly Chugh:

Keep going. Did you take the job?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah, I had just been laid off from Apple, yeah.

A couple weeks later my father visits me from Hawaii and I'm Sansei, he's Nisei, he's second generation Japanese American. And I tell him this story and I fully expect him to just go off, how dare this woman insult you?

You went to Stanford, you have an MBA, you've written ten books, you worked for Steve Jobs, blah, blah, blah, blah.

Instead he says to me, son, statistically a Japanese person cutting a hedge on Union Street in San Francisco, most likely you were the yard man. Don't get offended, take the high road and don't look for trouble where there isn't any.

Dolly Chugh:

And in some ways both are true. There's something to both of that.

Base rates are a thing, is what he was saying. And at the same time, we want to check ourselves in those moments and we want to help other people notice what they might not be noticing.

I am assuming we are both holders and targets of unconscious biases in different parts of our lives.

Guy Kawasaki:

Who isn't?

Dolly Chugh:

Exactly. Exactly.

Guy Kawasaki:

Wow. Do you think that the Democratic Party needs more heat or more light right now?

Dolly Chugh:

Let's start by explaining the dichotomy. So this is a metaphor that many have used and I couldn't actually find the original source, giving credit to the universe for this. The idea of heat versus light is how you try to make change or influence others.

And when you do it through using tools of light, it's gentle, and meeting people where they are, and teaching, and discussing, and explaining, and it's incremental. The heat based approach to making change pushes people beyond where they're comfortable. It's viewed as more radical than incremental.

By definition, it's meant to heat things up, to disrupt things that are happening. It may show up in the form of a protest or a disruption of a discussion or a pivot on a topic when people are like, just go with the flow. And this idea of heat and light, many of us have just by our temperament, or lean towards one or the other.

I would say I lean towards light in my personality. I have more of a people pleasing personality. And when I first started writing my first book, the Person You Mean To Be, I sent it to a dear friend from graduate school and asked for her feedback.

She's a social psychologist like I am. And she gave me lots of very thoughtful feedback about the sort of way in which I was explaining scholarship and et cetera. And then she said almost as a throwaway in her feedback, she said, “The Black Lives Matter folks, they might be a little annoyed with this book.”

And I was like, “Wait, I opened the book. I literally opened the book with me at a Black Lives Matter protest supporting, why would they be mad at me?”

She's like, “Yeah, but you also say you realize why you're at the protest. That protests aren't for you and this is all too much.”

And I was like, “Whoa, I do say that. But what I meant by it was that I'm more suited for light, not that I am against heat.”

And so what I did was I looked up the research, made by people who study social movements and they have found that movements that have lot more heat and not much light or vice versa, don't make as much progress as movements that have both, heat and light.

That balance is actually critical to moving things forward. And my hypothesis, I don't have data around this, but my hypothesis is that light changes minds, but heat changes systems.

And that's why we need both. So to your question, the Democratic Party and do they need more heat or more light? That's interesting. I'm trying to think how I would characterize the way it is now.

Because I think depending on who's seeing the Democratic Party, I think those who are not Democrats might feel the Democratic Party's throwing out a lot of heat.

But I think a lot of people within the Democratic Party think they need more heat. So I don't think I know the answer. I do think there's a dearth of understanding around a lot of these issues right now, which is why I'm writing the things I'm writing.

I'm trying to speak to people who are willing to learn and re-chart their minds that way, because I think there's a lot of hand waving and not a lot of listening and learning.

Guy Kawasaki:

I started off this interview with pronunciations of last names and I just want to return to that quickly, that you make a huge deal about that in your writing and including your website has a little audio snippet that you can click on to hear the correct pronunciation of your name.

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

Why is this such a big deal?

Dolly Chugh:

I think I've lived my whole life with people saying my name wrong and I've become very comfortable with that.

So I don't take that as seriously as I take taking other people's names seriously. And wanting to encourage organizations, schools, and companies to take advantage of the easily available free technology that we have available now that makes it completely trivial for us to be able to hear how people say their names.

And that should just be widely institutionalized. In this day and age, it shouldn't be that hard to know what is correct and to make the effort. Why is it important?

Someone's name is pretty much the first decision we make, parent makes or the family members make about that child. And for us to dismiss it is to really dismiss their underlying identity.

I will tell you in my own personal experience, I'm really not intuitive about how to say a lot of names.

And what I tend to do then is avoid the person, because I don't want to say the name wrong. And so then what happens is, I can see this in the classroom, when I have students from all over the world in my classes, my MBA classrooms and I'll see lots of hands up and I'll be like, I know how to say that name, I know how to say that.

I don't know how to say that name. And so I started asking my students to do a survey before this semester begins where they write out for me phonetically how to say their name and they record it using namedrop.io, which is one of the free apps out there, so I can practice before.

And it's not that hard. No one's asking us to be Meryl Streep. If we can learn how to say supercalifragilisticexpialidocious or the names on Games of Thrones, we can learn how to say Kawasaki. It's doable.

And so I think it's just a matter of, if I'm avoiding people whose names I don't know how to pronounce, I'm probably avoiding people who are different than me. So it just runs directly against the effort I'm putting in so many ways and so many other people are to be inclusive.

Guy Kawasaki:

Please explain why one should strive to be better or "goodish" instead of good.

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah. I'm on a mission to get us to let go of trying to be good people and to be goodish instead. And the reason is that, we tend to think of being a good person as either you are or you aren't. It's this very brittle either or identity. And in the work of a psychologist Carol Dweck, I would call that a fixed mindset. When you're in a fixed mindset, you don't view yourself as a being a work in progress.

So let's say, when it comes to drawing, I believe I'm not very good at drawing and I don't believe that I will get better with practice. And I might also believe in another area like pickleball, I might believe I'm very good at pickleball. And I do not need a pickleball lesson to get better at pickleball. I am good at pickleball.

And so in both of those areas, I'm showing a fixed mindset that I don't need feedback or practice or coaching. And I think that's how we tend to view being a good person. It is what it is. I'm advocating that we think of ourselves as goodish people.

That's a growth mindset, according to Dweck and colleagues. It's one in which we are always getting better. Maybe where like I am in drawing, we're not very good, or I see myself in pickleball, as being very good, but whatever it is, I could still get better.

And the key with that is that when I make a mistake, I own it and I try to do better. So when I misidentify that woman at the registration table at my MBA reunion, I learned something from it, rather than try to dismiss it or pretend it didn't happen or do all the things we do with our mishaps.

And so being goodish means I'm better today than I was yesterday. And the amazing thing about it, and we know this from so many parts of our lives, is we do this all the time. In our jobs, we're usually better now than we were a year ago.

In our relationships with our children, it depends how old our kids are, but we're trying to be better parents now than we were a year ago. In every part of our lives, we're getting better all the time. But there's something about this good person thing where we're frozen. And so being goodish is better than good, because it lets us get better all the time.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now I just want to point out for the listeners that you are the captain of your college tennis team.

So you’re saying you're good at pickleball is not, you just happen to be good at pickleball.

There's a little bit of background there in full disclosure.

Dolly Chugh:

Heard that. Fair enough.

According to the folks at the pickleball courts, I started playing a week ago, by the way, according to the folks at the pickleball courts, they're very different sports.

So I'm still trying to learn the differences. The rules are very different, I know that.

Guy Kawasaki:

But it helps to be a Division One College tennis player.

Dolly Chugh:

Absolutely. I've got some good racket skills.

Guy Kawasaki:

I suspect Roger Federer would be very good at pickleball.

Dolly Chugh:

Can you imagine? Did you hear LeBron James just bought ownership stake in a pickleball league?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah. How much could it cost to buy a pickleball team?

Dolly Chugh:

That's a good question.

Guy Kawasaki:

A thousand dollars?

Dolly Chugh:

If LeBron's doing it, must be big money.

Guy Kawasaki:

Yeah.

Dolly Chugh:

It's a big sport. I don't know about out by you, but here is the rage. It's huge.

Guy Kawasaki:

You begin your new book with just one of the most dramatic, falling on your sword episodes of business books ever. You're the first business book author to ever display humility at the start of his or her book.

Dolly Chugh:

Oh, that's too funny.

Guy Kawasaki:

So let's just talk about this, maybe traumatic is the right word, traumatic trip that aligned with the depiction of the American history with Little House on the Prairie. So just--

Dolly Chugh:

Sure.

Guy Kawasaki:

What was wrong there?

Dolly Chugh:

The trip was actually fabulous. It was the aftermath.

So I, like millions of others, have loved the Little house on the Prairie book series. Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote these books based off of her childhood and just colonial upbringing in her hardworking family.

And I read them to my children when they were young, the whole series, it took a year of reading to them every night. Eight books, 200 some pages each. And we really like the Ingalls family, became part of our family. They were like living with us.

They were in our minds and our hearts and our souls and so much so we decided to spend a family vacation driving around South Dakota and Minnesota to the places where the family actually lived, because they were real people, and see those sights and really breathe in the reality of their lives in this big prairie sky.

And it was going to be this educational trip and this fun trip. And it was a wonderful trip actually. It was terrific. But when we were there, I was, in the back of my mind being like, wait, this land was Native American land before the Ingalls got here. The Ingalls and lots of others who colonized that land.

And I was having these nudges in my head that I should try to understand that better and I should try to help my children understand that better. It's referred to very tangentially in the books and in a pretty derogatory way about when the settlers come in, the Indians have to move on and things like that.

And I'm sure I said something like one or two sentences when I was reading it to them, but never really explained to them. And so here we are and I'm with my kids, they're six and seven years old at the time, and they're old enough, kids that age understand fair play and justice and someone taking your things. That's definitely in their vocabulary.

And I could have broached the topic and I didn't. I just didn't. And in the years and the decades since then, I thought about that and realized that the issue wasn't really that I didn't know if they could handle it. Instead, I didn't know if I could handle it.

I had this idealized version of this American story and this narrative and this family and I just didn't want to touch it, because all these emotions would like, I wouldn't know what to do with them.

And so this book really comes, this book, meaning the book I wrote, A More Just Future, comes from me grappling with those emotions and not grappling with those emotions and wondering if there's someone out there who can help me figure out how to deal with this.

I'm a psychologist, I know there's research. I couldn't find anything that had been written up for a general audience. So in the end I wrote the book that I felt like I needed to read.

So the trip was really the catalyst, I would say, more than a trauma. I'm sorry. It was an opportunity to notice something that was bubbling inside me that I really hadn't dealt with.

Guy Kawasaki:

And if you were on the school board of your local school district and the topic came up of textbooks.

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

What history textbook would you select?

Dolly Chugh:

To be clear, I'm not a historian and in fact, I'm not even a history buff. I've written a book about how to grapple with history.

And so, while I wouldn't know what history book to select, what I would know is that we want to grapple with as full aversion of history as we can.

And so that means we want to hear multiple perspectives. I would look for a text and primary sources that give us multiple perspectives on events.

So if I were talking about when the Ingalls family was settling in Minnesota, I would also want to hear from the perspectives of the people who lived there before it was even called Minnesota and before the Ingalls family arrived.

Not only the white settler's perspective. And I think when we don't include that material, maybe some of the arguments we're hearing is that it creates shame and guilt.

What I'm trying to say is, we can deal with those emotions, we have tools for dealing with those emotions. Kids can deal with it and adults can deal with it.

What's much harder for us to do is unlearn it after the fact. It's clear from research that it's easier to learn something the right way the first time than have to go back and unlearn it and relearn it.

And that's exactly what, when that trip with my kids and the year of reading them those books, I set them up for having to do a whole bunch of unlearning down the road.

Guy Kawasaki:

So your head must literally be exploding when parents around the country are trying to ban Black studies, basically.

Dolly Chugh:

Being a parent's hard. And so I get that there's a million ways in which a parent tries to protect their children. I don't agree with all the ways, but I get it.

But yes, I don't think parents are doing their kids any favors there. I think their kids are so much more resilient and capable and we are setting them up for a much tougher future, not just in terms of the unlearning, but there's research by a psychologist, Phia Salter or and others that talks about, how much better we are at seeing systemic, let's say, racism in the present when we know just a little bit of history about the past.

And when we don't give our kids that little bit of history about the past, we really set them up to not understand what's happening right now.

And so when they look around the world around them and they say, Black people live in these neighborhoods, and white people live in those neighborhoods, and Japanese people live in those neighborhoods, and Indian people live in those neighborhoods and it just looks preordained. It doesn't look like there's a cause and effect for it.

It makes it really difficult for them to deal with the kinds of tensions and discussions and conflicts that they are going to deal with. And not to mention the lost friendships, the lost opportunities, the lost humanity.

So I think we have so many opportunities to help our kids through how we teach history that maybe we're scared of, but it's not going to be as scary as we think.

Guy Kawasaki:

If you buy the theory that if you don't understand history, you're doomed to repeat it, it seems to me that with so much history being whitewashed, we are going to repeat a lot of problems.

So how do we get out of this vicious cycle?

Dolly Chugh:

At one point I googled that famous phrase to see if there's any evidence to actually support that statement. And I think in the end it was inconclusive if I remember right.

So even if we don't buy that premise, I think we want to stop. We want to know the history, because even if it doesn't change what happens in the future, it absolutely changes what happens in the present. How do we break the cycle?

I think right now we're having this argument of should we teach it or shouldn't we? It's like, we should or we shouldn't as if those are the only two choices.

And what I'm trying to offer is a different approach that we should do it, but it isn't like we just drop this hot potato on people and see what they do with it. It's that we have some oven myths we can out on, we can use some tools that help people deal with emotions like shame and guilt and disbelief.

And it makes us more resilient when we want to be like, no, or throw the potato, it's too hot. We can be a little more resilient towards it. And I talk about being a gritty patriot using the work that, as psychologist Angela Duckworth has done on grit, passion and perseverance and pursuit of a meaningful long-term goal, is something we can apply here.

That rather than thinking of love of country, I love my country so deeply, but is it something I'm just entitled? I'm just entitled to love my country? Or should I have to work at it? Should patriotism be something that is a meaningful long-term goal, that's going to require some passion and perseverance from me. And I'm offering that being a gritty patriot might be the path forward.

Guy Kawasaki:

You mentioned a really great contrast between the United States and Germany.

So if you, not you, but if the listener ever goes to Berlin, it's hard to miss that memorial in the middle of Berlin and it is a very eerie memorial.

Is there any scientific research or proof that the German approach to the Holocaust, which is not denial, has proven to be a better approach?

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah, that's a great question. I actually haven't been to Berlin. I certainly write about that in my book and I write about what I've read about it, but I haven't been there myself.

So it's interesting to hear your personal observation. So I don't know of scientific studies that have explicitly studied it in the way you just described, but I'm following a line of logic, which is, if we don't know about something, it's really hard to acknowledge it.

It's really hard to apologize for it. And if its impact is still being held today and some people are feeling the impact and some people aren't, then you are doomed to have conflict, because those people who are feeling the impact, still acknowledge and remember it.

And those people who don't even know what happened are not sure why those people are so upset.

So it just seems so logical to me. From what I read about what's happening in Germany, it's not like it's a utopia in terms of where things stand now, but at least there's an effort being made.

And I think that's where a lot of us are struggling. We want to make that effort. I think many people want to.

That's what I'm hearing in reaction to the people who are reading my book in advance is they're saying, ah, this is the thing, I don't know what to do about and how to think about these things.

And I think it wasn't just me who was struggling in this area, a lot of us are looking for a way forward.

Guy Kawasaki:

Would you discuss the most important things that we need to unlearn?

Dolly Chugh:

I have a chapter that focuses on racial fables. And racial fables are narratives about how change has happened so far.

So for example, how did the Civil Rights movement unfold?

And a lot of us know the story, for example, of Rosa Parks, except the story we know about Rosa Parks who's, other than US presidents, I believe the most famous name in America.

It turns out we don't know the story of Rosa Parks. What's amazing is the story we know is largely untrue. It's like a little kid's version of the story that was sanitized and simplified that all of us just accepted as grownups.

And historian Jeanne Theoharis has written the first definitive, she's a scholar, but it's a general audience book, but it's heavily footnoted, biography of Rosa Parks in which she shows that literally almost everything we think is true, beginning with the fact that we all describe her as elderly, she was forty-two. She was forty-two, this elderly seamstress on the bus.

She also had a long life history of being rebellious, of being an activist, of spending most of her evenings and weekends volunteering for the NAACP, fighting racism. This is before she wouldn't give up seat on the bus.

So there was nothing surprising about what happened that day. The only thing that was surprising is that it happened to be that day. The reason that's so important, that we realized that what we've learned as a racial fable, not the truth, is that it gives us this false impression about how change happens.

We expect a singular hero to rise and say, Oh, by the way, I don't know if you all noticed, but this isn't really fair.”

And then we expect everyone else to be like, “Oh my gosh, you're so right. Oh man, how did I miss that? Let's fix it. Fixed.”

And it feels like a one and done thing. But what actually happened is, there were many people who wouldn't give up their seats on the bus before Rosa Parks. No change came as a result. They were not treated as heroes at all.

And they were in fact vilified for their actions by the people who felt they were being disrespectful and breaking the law and not following cultural norms and so forth. And so this racial fable leads us to look for someone who we think is Rosa Parks today, who's going to be very docile, palatable.

And then we wait for everybody to agree with her and then we wait for Martin Luther King to give his speech, and then it all feels very simple. And we forget that Martin Luther King was viewed as a radical and as someone who was moving too fast by the vast majority of white Americans in the sixties, and he and she were just two of thousands and thousands of activists at the time, and before that time and since that time.

So this was not a couple of heroes who got instant results. It was many people whose results almost always failed until they didn't.

And so I already forgot the question. I'm on such a role, Guy, but I think--

Guy Kawasaki:

The question was about--

Dolly Chugh:

What was it?

Guy Kawasaki:

What to unlearn.

Dolly Chugh:

What to unlearn, yes.

So we want to unlearn racial fables because, this is a great example about how it hurts us in the present.

It means that when we're sitting in a meeting at work and somebody is really getting animated in trying to question our hiring practices, and we are like, why are they being so divisive? Why are they moving too fast?

And we want to just dismiss them and tone police them when they're bringing heat, not light, we're failing to see that this is what it feels like to be around a Rosa Parks or a Martin Luther King.

This is how change happens.

Guy Kawasaki:

I must admit that I didn't know all the background of Rosa Parks until I read your book. I fell into the fable of seamstress gets on a bus, decides to stand up for herself at that day, without any forethought and becomes a hero.

Dolly Chugh:

The book I just referred to, the definitive biography, is being made into a movie that's releasing this fall. I think it's by the same title, The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks.

And I haven't seen the movie, but I have read the book and I expect the movie has some wonderful filmmakers and storytellers behind it, including Soledad O'Brien. So I think it's going to be excellent.

And either the book or the movie, I highly recommend.

Guy Kawasaki:

Do you have any tips on fable detection, therefore?

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah, absolutely. Yeah. There's three red flags that I think are really easy to keep in mind. One is to look for when there's a very clear cause and effect. When everything just looks like, “Oh, this happened, Rosa wouldn't give up her seat and then everyone agreed we should change the laws.”

That feels too clean. Things don't happen that cleanly.

So clean cause and effect are a good sign, a good red flag that you're dealing with a fable. Flawless heroes is another red flag. When we have a hero that just seems unilaterally perfect and always says things perfectly and has made no mistakes.

We know that's not how human beings are. That's a sign that we have sanitized somebody and created a fable out of them. And then the third red flag would be good guys beat bad guys all the time.

This is a spinoff worked by psychologist John Jost called System Justification Theory.

I've simplified it for my own thinking as ‘The good guys win’, mindset. And in that mindset we have this psychological impulse to see those who win as the good guys and those who don't as the bad.

However, what the research shows is that leads us to justify the status quo even when it's not in favor of justice, because we want to see that, good guys win, outcome. When we're hearing a narrative in which it seems like the good guys always win, chances are we're not hearing the full story.

Where there's some instances where the good guys don't win, that we're not hearing. Or maybe there's a richer narrative to be understood about good and bad guys.

Guy Kawasaki:

What's the right word? I think you glanced upon this topic and now I want to force you into it.

Dolly Chugh:

Okay.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay?

Dolly Chugh:

All right. What is it?

Guy Kawasaki:

Is divisiveness such a bad thing?

Dolly Chugh:

No, it's a good thing. It's not always a fun thing. It's not always a comfortable thing, but the Civil War was divisive. The Civil Rights movement was divisive.

Change in the fable of change is not divisive, in the reality of change it is.

And so the question is not, can we make change without it being divisive? It's, how can we, when things are divisive, understand how to grapple with that and move to a better place as a result? Let's make the divisiveness worth it.

Guy Kawasaki:

Now, coming to the sixty-four million dollar question about your book, which is, what are the tools that we can use to come to grips with our past? Our true past? Our divisive unfabled past?

Dolly Chugh:

In the book I offer seven tools, and I'm sure we don't want to go through all seven of them, but let me pick one or two. So we just talked about one, which was the idea of rejecting racial fables. Let's actually recap the ones we've already talked about, because we've covered a few.

So one was rejecting racial fables and one was building grit. Having that passion and perseverance for the meaningful long-term goal of love of country.

Another one that I think is really useful is embracing paradox.

Embracing paradox is the idea of holding contradictory truths in our head. And our minds don't like to do this. Our minds like to smooth over contradiction.

And what confuses this smoothing process when we say things like, ‘Our Country's forefathers were extraordinary people who did extraordinary things and had a vision they implemented around liberty and equality and justice.”

True statement. Our forefathers, many of them, while they were enacting that vision, enslaved other human beings, separated families, engaged in violence against them and didn't treat them as equal to white humans or to male humans. Those are two really contradictory statements.

And yet I think it's hard to argue that they're not both true. The narratives we've learned, for most of us have been that first version of it. And what the paradox mindset would suggest is that we want to hold both of those truths at the same time.

Scholars on paradox like Wendy Smith and Marianne Lewis talk about when we embrace paradox, we just tell our brains to allow both of these things to be true at the same time, we actually unleash all sorts of positive benefits for ourselves.

And this isn't just in the field of history. It's in anything, business, we're more resilient, we're more creative, we're able to gate things that would lead us to speed bumps that might slow us down. We're able to make it through that speed bump because we're not tripped up by these contradictions.

So the paradox mindset, I think is a really powerful tool. And I write in the book about the former mayor of New Orleans, Mitch Landrieu. He got some national visibility when he, at the suggestion of jazz musician, Wynton Marsalis decided to take on the task of taking down confederate monuments that were in public spaces in New Orleans.

This was in the aftermath of Katrina when there were obviously tremendous rebuilding efforts underway. And when I interviewed him, I've seen all these news reports and everything, and I expected to interview him and hear someone who was just like, no, we have to tear that stuff down. And instead he just kept talking about building.

And I was like, I thought we were talking about tearing things down. So at one point in the interview I was like, just to understand, you keep talking about building, but I thought we were talking about tearing things down.

And he said, and I may not have the quote exactly right, but the exact quote's in the book, he said something that was essentially like, “Most of our lives, we live in a contradiction.”

And that's when I realized that's why he was able to hold this love of this city that his family's been in for generations and speaks so lovingly of building it up while at the same time talk about monuments that are central to its history and to its public spaces and tearing them down.

And both of those things could be true.

Guy Kawasaki:

You could make the case that someone who truly loves something will see its faults and want to make it better.

Dolly Chugh:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

As opposed to just think it's perfect and static. Right?

Dolly Chugh:

Absolutely. And in fact, that is the case, that you just said so beautifully.

And one of the parallels I offer is that, for those who are parents, if we only love the Instagramed version of our children, where does that lead us with our children? How are we going to teach them and love them into adulthood and guide them if we only can see that version of them?

As opposed to notice that, sometimes they interrupt people and they really need to learn not to do that. We need to be able to help them see ways in which they can be better.

And I think the same is true of our country. I don't love my children less when I help them try to be their best selves. And the same is true of how I love my country.

Guy Kawasaki:

Maybe I should interview your children.

Dolly Chugh:

Oh God.

Guy Kawasaki:

I have done that a few times where I had a guest and then I would interview the spouse, or I would interview someone mentioned, a boss in it.

Dolly Chugh:

That's cool.

Guy Kawasaki:

It's quite interesting. The most extreme example of this was probably when the founder of Khan Academy tells the story of how he started Khan Academy to help his cousin or niece learn algebra.

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah, so you went to the niece?

Guy Kawasaki:

So--

Dolly Chugh:

I love that.

Guy Kawasaki:

I requested and received permission to interview her, say, so your uncle told me that this is how it went down. Is this all true? It was really a great interview.

Dolly Chugh:

I've got to go find that episode. That's so cool. I guess I did a version of that in my first book where I interviewed Jodi Picoult, the best-selling author, and she kept referring to her son and son-in-law as having taught her certain things.

And I ended up going back to her via email and saying, is there any way I could talk to your son and son-in-law? And so the way I ended up writing that chapter, they're actually very central in the story that we tell.

Guy Kawasaki:

It would not occur to most people to go find those two people like you did, and to get the other side. Which in a sense is part of your book's message, that let's find out the other side of Rosa Parks.

Let's find out the other side of other things. I don't know if it was a paradox between them, but it certainly wasn't as probably clean and one sided as most authors would present.

Dolly Chugh:

That's right. It definitely wasn't a paradox, but it was a fuller, more interesting story to hear it from three different perspectives. So on the one hand, yes, our minds like things simple and without paradox.

On the other hand, that's like the most boring movie ever. Every movie you want a hero's journey and some complexity and some character development. And part of this is just creating the same thing we like in our entertainment, in our reality.

Guy Kawasaki:

Let me fantasize here. So let's suppose that Joe Biden or his wife listens to my podcast.

Dolly Chugh:

I bet they do.

Guy Kawasaki:

I doubt it. But let's just fantasize.

Dolly Chugh:

I bet they do, Guy.

Guy Kawasaki:

And they hear this amazing episode with you and they say, she has a lot of great ideas about how we can bring this country together.

People who both love the country have such different opinions about what we should do.

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

So Joe or Mrs. Biden calls you up and says, “Dolly, can we talk to you? Can we have a beer? Can we get some ideas from you? Can you give us your top three tips for making America great again?”

And then what does Dolly say?

Dolly Chugh:

Oh my goodness, that's a good question. Let's see if I could come up with something on the spot.

Guy Kawasaki:

Hey, you're a professor, you're captain of a tennis team, Harvard. No. Was it Cornell and Harvard?

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah. Cornell undergrad. Harvard MBA.

Guy Kawasaki:

Okay. If not you, who could possibly explain this to the Bidens.

Dolly Chugh:

Your faith in me is so impressive, Guy. Let's see. I would say--

Guy Kawasaki:

My podcast is called Remarkable People, not Mediocre People.

Dolly Chugh:

I love it. So the question they're asking me is, what are three things we can do to move forward?

Guy Kawasaki:

Yes.

Dolly Chugh:

If I had that conversation with President and Dr. Biden, I think I would really want to focus on the connecting the dots between the past and present.

I feel like that's where, for me, I'm speaking personally as someone who's highly educated and had every opportunity to understand the fuller version of history and still doesn't, and didn't.

And so I think the more we can do to just make those connections between the past and present visible, and we can do that, I think, in ways that don't have to be boring. Like I said, I was not a strong history student growing up. I don't even know if I get the History Channel.

A lot of people think of history as boring. I'm not saying it is boring, but I think there are entertaining ways to make it come alive.

And so I would say, what can we do to connect the dots between the past and the present? One of the things I talk about in the book is, the long time ago illusion. The idea that things seem like there were so long ago, I was recently looking at this little, I guess meme you would call it, that was saying that Anne Frank, Martin Luther King, if they were alive today, would be the same age as Barbara Walters.

They were all born in 1929. So we think of the Holocaust as a long time ago. We is not everybody, but many people think of it as so long ago. Or the Civil Rights movement as so long ago. And yet Barbara Walters is alive and well and was on The View not so long ago.

How can we really bring the past into the present so that we can see how relevant it is, that it isn't a long time ago in the sense that it's not relevant. So I think I would come up with a better answer if I had more warning, but I think that's where I would start. With connecting the dots.

Guy Kawasaki:

Another Barbara Walters type of story, which I got from you is George Takei.

Dolly Chugh:

Yes.

Guy Kawasaki:

George Takei is still alive.

Dolly Chugh:

I know.

Guy Kawasaki:

And he was in Manzanar or I don't know, Manzanar, but one of those camps.

Dolly Chugh:

Yes, yes. Extraordinary.

Guy Kawasaki:

It's not that long ago.

Dolly Chugh:

It's not. And actually, I listened to most of one of the episodes you recorded. She wrote a wonderful book that you talked a lot about, who also had a similar experience and yeah, Star Trek fame, what celebrity has been as relevant for as many decades as George with millions and millions of followers now on social media.

But one of his missions is that he really wants people to understand that when he was four years old, he and 120,000 other Japanese Americans, he and his parents were imprisoned for years, behind barbed wire, soldiers with guns not letting them leave, simply because they were believed to be aligned with the enemy. For some possible future crime they might commit.

This was during World War II, when the US and Japan were at war and they lost their homes, they lost their jobs. This is an extraordinary thing.

I was trying to imagine if this were to happen to my family, if the United States and India were to go to war and my family, which has lived in this country for fifty plus years, is deeply in love with this country, were we suddenly to be assumed the enemy and locked up?

And I would just leave my job at NYU and all our life savings and my children would be in prisons?

And yet George lived through this, as did so many.

Guy Kawasaki:

If the United States went to war with India and all the Indian and Indian descent people were stuck in prison camps, Silicon Valley would implode. Would implode.

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah.

Guy Kawasaki:

You mentioned this concept of connecting the dots, which I will mention is, that's just one more of the seven tools, but what happens if you connect the dots, you see what's happening to Black people and they're getting shot and killed, but you have to connect the dots to slavery.

It's not independent. Those two things are a direct line from one to the other. So connecting the dots is not always going to be unicorns and pixie dust.

Dolly Chugh:

Yeah, no, I think that is the challenge. And that's why we don't want to connect the dots. Even if we don't consciously resist it, we unconsciously resist it.

And so we want to be able to think about the good old days without realizing the good old days weren't always good for everybody all the time.

So, that's where coping with these emotions that come up. And so some of the tools that I offer in the book are about how to affirm our values, the things we believe in.

Research shows that simply thinking about the values you believe in, maybe writing about them as little journal activity, actually makes us more resilient when those emotions come up and we want to push away.

So if I think about the values I care about around equality, around democracy, around liberty, around love of country, I can use that to anchor me.

That when I go to listen to that podcast and they start talking about slavery and the sort of ways in which that led to a lack of, forty acres and a mule, which apparently that phrase, which I've heard my whole life actually never really happened.

We never actually gave forty acres and a mule to those. So we never actually apologized for slavery.

To this day, the United States government has not apologized for slavery.

Those are hard things to grapple with. So the values affirmation is one tool that people have shown, in other domains that I think could be applied to this domain, to help us push through and keep listening, keep learning, keep processing those truths.

Guy Kawasaki:

That's a good way to end this podcast.

Dolly Chugh:

Thank you so much. I really appreciate that. And it's really an honor to be on your show. I appreciate how thoughtful you prepare and formulate your questions.

And Madisun, all your hard work in the background. Thank you.

Guy Kawasaki:

And pronounce names.

Dolly Chugh:

I know.

Guy Kawasaki:

I hope you enjoyed this episode with Dolly Chugh. She has such a powerful and valuable message these days.

I hope you take her seven tools and her body of knowledge and expertise and in the words of Steve Jobs, “Make the world a better place.”

Don't forget she has a new book out. It's called A More Just Future: Psychological Tools for Reckoning With our Past and Driving Social Change.

I'm Guy Kawasaki, this is Remarkable People. My thanks to Katy Milkman for making this episode possible.

Jeff Sieh, Peg Fitzpatrick, Shannon Hernandez, Madisun drop-in-queen Nuismer, Alexis Nishimura and Luis Magaña.

The Remarkable People Team. We're all trying to make you more remarkable.

Until next episode, Mahalo and Aloha.

Sign up to receive email updates

Leave a Reply